Today’s successful author will sooner or later be invited to sell his or her personal papers. Sooner rather than later most likely, and not just papers, manuscripts, typescripts, notebooks, but electronic data too, emails, chat messages, the lot. Everything you have written, then, but also everything you will write. Your emails to your children, your grandchildren, great-grandchildren, your ex-wife or husband, present partner, future partner, lovers, ex-lovers, dying parents, estranged cousins, needy friends, your application for this or that grant, your fencing with would-be publishers or agents, your self-promotional lobbying for the Pulitzer or the Booker, deluded dreams of the Nobel, half-truths for the taxman, heated exchanges with magazine editors when payment is delayed.

Of course, assuming an author didn’t take preventive action and was still highly regarded at death, much of this material would eventually have been gathered in public archives anyway. The interest in private papers goes right back to the ancient world. Many authors have sold or bequeathed their manuscripts to appropriate archives. The letters of D. H. Lawrence (in eight volumes) or Virginia Woolf (in six), have come to seem as much part of the authors’ oeuvres as their novels. What has changed is the predictive and competitive nature of the acquisitions, with writers being selected on the basis of a few years celebrity or a prestigious literary prize and invited to sell their correspondence even before it is written. What makes this easier is that now we all use email we get to keep what we write, rather than consigning our letters to someone else’s hands. The only problem is preserving all the damn things.

For the author, needless to say, the lure is money. Large sums can be involved. The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas reputedly paid $1.5 million for J. M. Coetzee’s papers. The British Library more modestly gave £110,000 for the manu-scripts of novelist Graham Swift, announcing as a special attraction “a tape recording of the answer phone messages he received on the night he won the Booker Prize.” We all love a winner.

But not only money. Any organization that spends a considerable sum on you will also have an interest in promoting your reputation. They don’t want to be accused of having thrown cash at a lemon. So there will be exhibitions, seminars, features of archived material. You will be talked up. Everything will be done to transform ephemeral celebrity into durable literary glory. With your papers now declared part of the world’s cultural heritage, you have an edge over your rivals and are paid into the bargain. “Unto he that hath shall more be given” is a logic that always holds in the art world.

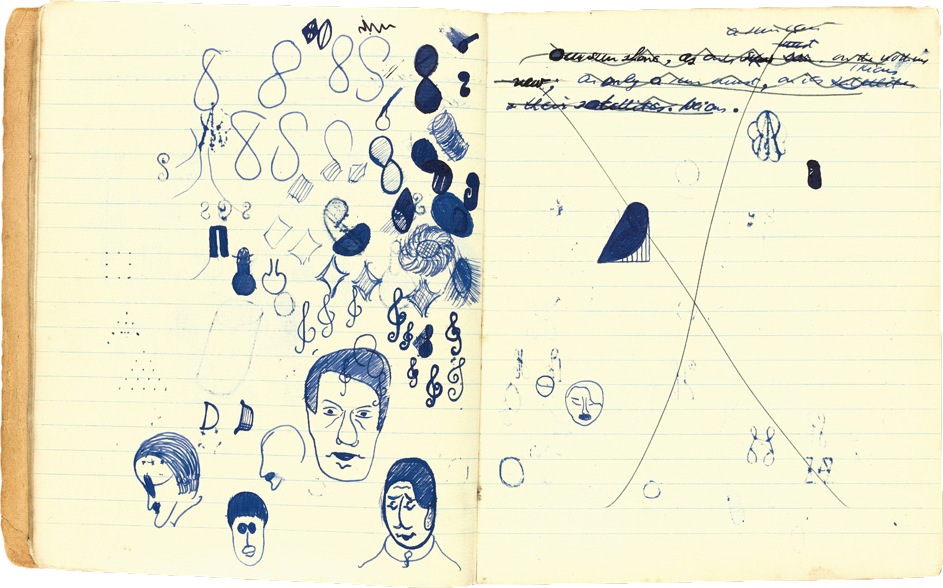

My agent mentions this possibility to me and immediately I’m enthusiastic. In these days of falling advances and general publishing crisis, how many writers would not welcome the arrival of a major injection of liquidity? And how nice, frankly, to be shot of those yellowing manuscripts gathering dust in the attic. “The Jim Crace Papers,” warns the Harry Ransom Center website, “include a small amount of material that was exposed to moisture and suffered minor mold damage…. Patrons may consider wearing gloves and a dust/mist respirator while handling this material.” I remember the last time I moved my boxes of unpublished manuscripts they were full of silverfish. Turning insect-ridden papers into cash has to be a good idea.

And privacy?

No problem. An author can stipulate which correspondence must not be released before you are, as it were, safely dead. Or before your wife/husband/partner, is dead. (It might be wise to avoid telling your spouse about this clause.) Some arrangements will even admit to the existence of material so toxic it must not be released until a hundred years after the author’s ashes have been scattered in the rose garden.

So what could possibly be wrong here?

I imagine sealing such a deal. From now on everything I write has a public. Everything I dash off is to be a legitimate object of scrutiny for some future researcher. Someone somewhere will one day become an expert in all my prevarications, give his life to understanding how I screwed up mine. And knowingly or otherwise any person I correspond with is also, in a sense, party to that publication, that exposure, could be promoted or damaged by his or her dealings with me. Immediately I fear a drastic reinforcement of my superego. Surely I will hold myself back in these altered circumstances, as when my mother used to warn me that God saw everything I did and even thought, so that one of the reliefs of losing faith was the recovery of a little privacy.

Advertisement

Or alternately I might deliberately start writing all kinds of outrageous things in order to impress. I’ll be dead, who cares; this will wake up the balding scholar with his gloves and respirator, this will get them talking about me in the twenty-second century.

Or more likely I’ll find myself making a huge effort not to change the way I write and relate to others just because the stuff is destined for the archive. No, that future expert, future notoriety is not going to psyche me out. I’m going to remain exactly as I was. In fact, now I see the possibility of a fascinating Ph.D. thesis that examines the extent to which authors’ correspondence changes once they sign their archive agreements. Or doesn’t change, perhaps; some authors always thought their every word worthy of inspection. Departing on a first trip to Paris, aged twenty, Joyce told his brother Stanislaus that if anything should happen to him his papers should be sent to all the great libraries of the world.

But needless to say the day will come when I want to write some letter so mean or libidinous or just downright evil that I wouldn’t want others to know about it however dead I am, ever. If one is vain enough to want every pen mark to be an object of study, one is doubtless also sufficiently self-obsessed to want something to remain hidden. I imagine opening an email account that the archive isn’t aware of to start a scabrous correspondence that will be all the wilder for the rush of adrenalin arising from my being free at last of those professorial minders, as yet unborn.

Then I feel guilty. They paid for everything. What am I doing trying to hold a bit back? What if they find out? Could the person I am writing to now blackmail me by threatening to expose this subterfuge? Or alternatively try to sell correspondence that has escaped the archive? If he/she does so could the archive that bought the whole caboodle claim that the work was theirs and illegally sold?

Or what happens if I change my mind? If suddenly the idea of a cult of me becomes an atrocious burden. I want to burn everything, delete everything, not to pollute the planet in any way, not leave any footprint at all. Such changes of heart are not unthinkable. Dickens burned his correspondence. It is harder to think of a man vainer than Dickens. Likewise Thomas Hardy. Perhaps one day I will suddenly be overwhelmed by the realization that it really isn’t healthy for anyone to be wasting his life going through the peelings of mine. Isn’t there simply so much private material now floating around on the Internet, much of it apparently inerasable, that to add to the miasma seems vulgar and disheartening. After all, deep down one knows that if there were no money involved, one would definitely hold on to the stuff to the end and make the decision then, even if it’s only the decision to let posterity do as it will.

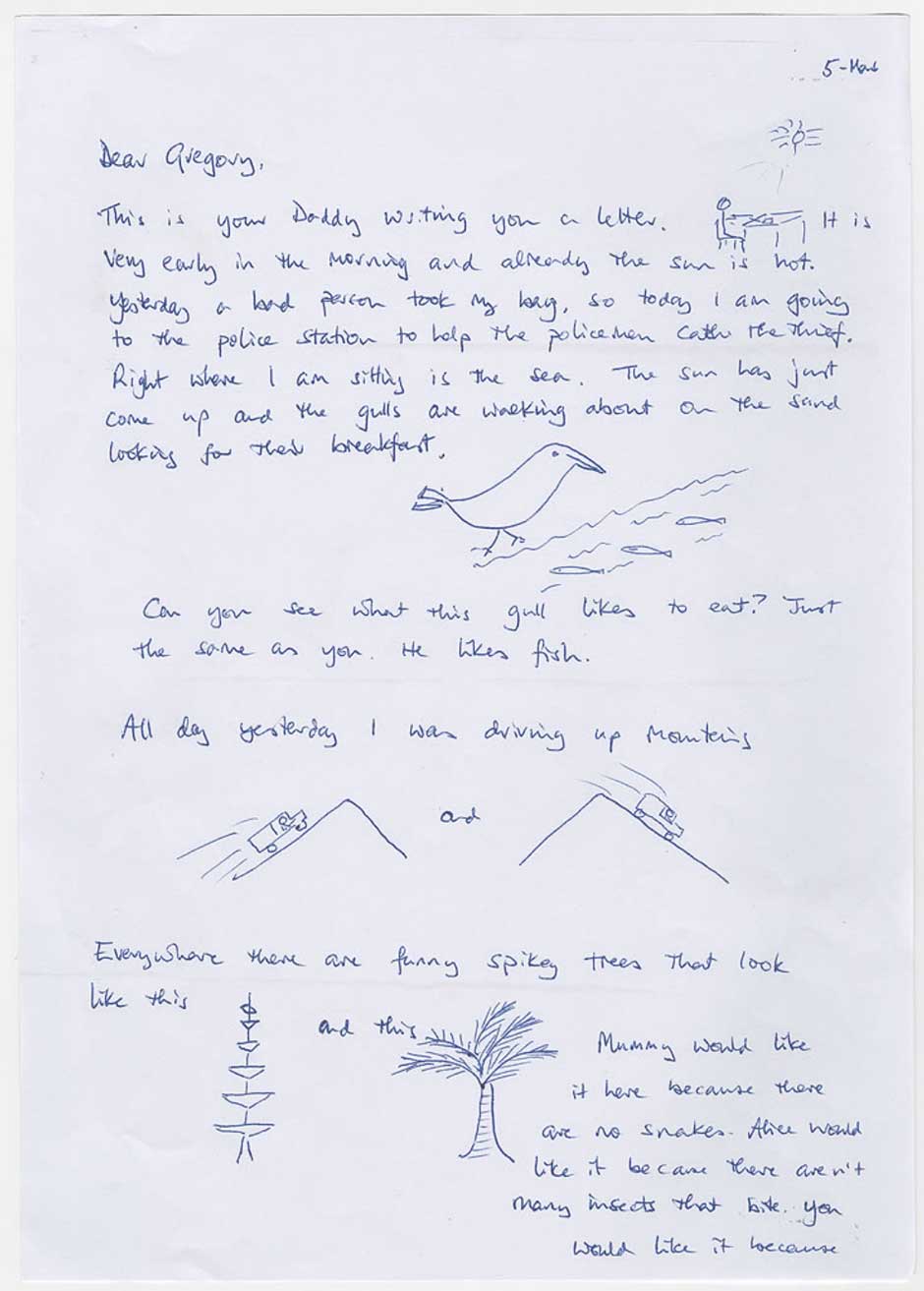

Meantime, stepping back a little, isn’t it extremely odd that the academy, which generally frowns on “biographism,” should so solemnly endorse this vast accumulation of memorabilia: Graham Swift’s correspondence with Ted Hughes, the British Library tells us with evident enthusiasm, “includes tips for fishing the River Torridge in Devon, together with Hughes’s handwritten sketches marking ‘fish traps’ along the river.” Public money well spent, no doubt. On the other hand, it may also seem a little paradoxical that someone like myself, who has always believed that life and work cannot be separated, should feel so circumspect about the phenomenon.

But no. It is because life and work are as seamless as mind and body that one has to sit up and pay attention here. Alter the terms of an author’s relationships with others and inevitably you alter his or her work. Perhaps it now seems that an email or text message requires as much craft as your novels. Clearly this shift of creative effort is already occurring on Twitter. But a tweet is of its nature in the public domain, while the recipient of an email has a right (or doesn’t he/she?) to imagine the exchange is private, that you are not inserting elements for the admiration of others, or excluding elements to hide them from others. How ironic to have fought government surveillance all one’s life only to allow it by a cultural institution.

Going back to my own dusty boxes, while I would definitely glad to see the back of the manuscripts and their silverfish, I can’t help wanting to reserve the right to a good bonfire of the correspondence. Or deletion of the email account. But perhaps I will think differently if an offer is large enough.

Advertisement