Two poets, Russell Edson (1935–2014) and Bill Knott (1940–2014), both of whom I was friendly with and whose poetry was very important to me, died this spring, each one leaving behind many original and memorable poems and many devoted readers, despite keeping their distance from our literary scene. Anyone who was fortunate enough to hear them read their poems over the last forty-five years is not likely to have forgotten the experience. Edson made his audiences roar with laughter or sit in shock at what they were hearing, while Knott always had some eccentric stunt to mystify and delight them, like the time he walked out on stage at the Guggenheim Museum carrying a brown paper bag, from which he’d extract a poem written on small notebook paper, hold it up to the light, read a few marvelous lines of poetry and then stop, telling the people this poem is complete shit—and then go through the same routine again and again before deigning to read an entire poem.

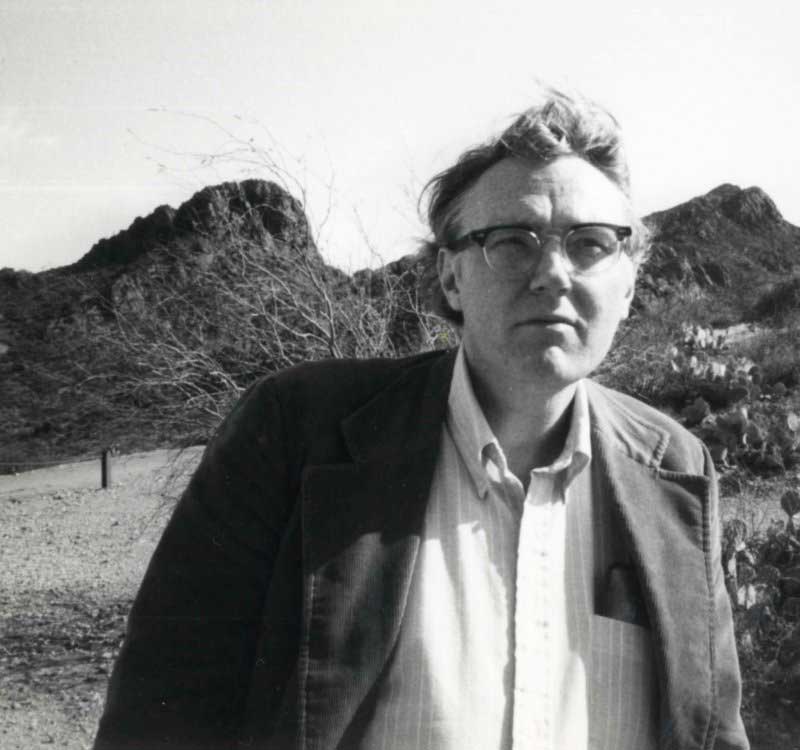

The son of Gus Edson, a famous cartoonist who created the character Art Gump, Russell Edson was born in Stamford, Connecticut and lived in the area for the rest of his life, leaving home only to attend the Arts Students League in New York in his teens and in later years to give occasional readings or poetry workshops at colleges and universities. He wrote what he called prose poems and others described as little fables, but neither label was especially illuminating. Not only did these “poems” not look like anything one had ever read, but what went on in them was downright peculiar. “Let us consider the farmer who makes his straw hat his sweetheart,” one of them begins. In other poems one reads about the rich hiring orchestras and having the musicians climb into trees, sit in the branches among the leaves, and play Happy Birthday to their dogs, a girl teaches herself to play piano by taking it for a walk into the woods, a man falls in love with himself and is unable to think of anything else but himself, being immensely flattered that no one else had ever shown him that much interest, one of Darwin’s ape ancestors is swinging from tree to tree when a female ape slaps him on the back of his small, but promising head, screeching whatcha thinking about, you brainless brute. And then there is this:

Counting Sheep

A scientist has a test tube full of sheep. He wonders if he should try to

shrink a pasture for them.

They are like grains of rice.

He wonders if it is possible to shrink something out of existence.

He wonders if the sheep are aware of their tininess, if they have

any sense of scale. Perhaps they think the test tube is a glass barn…

He wonders what he should do with them; they certainly have less meat

and wool than ordinary sheep. Has he reduced their commercial value?

He wonders if they could be used as a substitute for rice, a sort of woolly

rice…

He wonders if he shouldn’t rub them into a red paste between his fingers.

He wonders if they are breeding, or if any of them have died.

He puts them under a microscope, and falls asleep counting them.

For many readers, calling something like this poetry is not just preposterous, but an insult against every poem they have ever loved. Edson said that he wanted to write without debt or obligation to any literary form or idea, a poetry free from the definition of poetry and a prose free of the necessities of fiction, free even of their author and his own expectations. What made him fond of prose poems, he said, is their clumsiness, their lack of ambition, and their sense of the funny. If the finished product turned out to be a work of literature, this was quite incidental to his intentions. In other words, he thought of poetry as a cast-iron airplane that sporadically flies, chiefly because its pilot doesn’t seem to care if it does or does not. The real surprise comes when we realize that what we are reading is not the work of a jokester, but of a satirist and a serious thinker.

Antimatter

On the other side of a mirror there’s an inverse world,

where the insane go sane; where bones climb out of the

earth and recede to the first slime of love.And in the evening the sun is just rising.

Lovers cry because they are a day younger, and soon

childhood robs them of their pleasure.In such a world there is much sadness which, of course,

is joy…

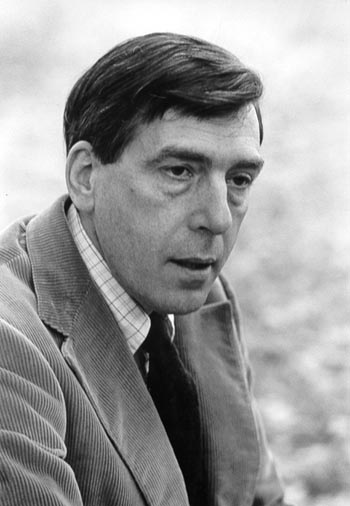

Bill Knott was born in Carson City, Michigan in 1940. His mother died when he was six and his father when he was eleven. He grew up in an orphanage, which he left at the age of fifteen when he suffered a nervous breakdown and was sent to an insane asylum. Released after a year, he went to live with an uncle who was a sharecropper on a farm in Michigan, and after finishing high school he was drafted into the army. I met him in Chicago in 1965 through a friend, who told me about this extraordinary young poet who worked on the night shift in a hospital emptying piss pots. One Sunday afternoon, he took me to see Bill in a rooming house where he lived. We knocked a long time before he opened the door and let us into a room full of books, empty Pepsi bottles, and one huge poster of Monica Vitti, the Italian movie star, hanging over his bed. He offered us each a Pepsi and we stayed for hours talking about poetry.

Advertisement

I don’t remember when Bill and I started showing each other poems, but we kept in touch by mail after I returned to New York. Then one day I heard that a mimeographed letter supposedly written by a friend of Bill’s was making rounds. It apparently announced that Bill had killed himself because he was an orphan and a virgin and because he couldn’t endure any longer not being loved by somebody. I didn’t know what to think, since I had had one of my letters to him returned earlier that week with the word “deceased” written on the envelope in Bill’s unmistakable handwriting, and figured he probably just wanted to be left in peace for a while. Not long after, his first book, The Naomi Poems: Book One: Corpse and Beans, was published bearing the name Saint Geraud (1940–1966) with the introduction explaining that the name was a pseudonym for a young poet who in fact was very much alive and writing. Of course, when my copy arrived in the mail, it was signed: “Knott (1940–1966)” and had that bit about the author being still alive crossed out in the introduction.

I find it still to be an incredibly fine book of poems. Knott was unlike any American poet of his time, because he was influenced far more by European and South American poetry than by our own, with the exceptions of James Wright and W.S. Merwin. I recall him talking to me about Rimbaud, Trakl, Char, Vallejo, Desnos, and Lorca, and there are traces of them all in The Naomi Poems. As in his future books, there are love poems, angry political poems, poems about unhappy children, comic poems, and many poems about death, like this famous one:

Goodbye

If you are still alive when you read this,

close your eyes. I am

under their lids, growing black.

Other books followed: Auto-Necrophilia, (1971), Love Poems to Myself (1974), Rome in Rome (1976), Selected and Collected Poems (1977), Becos (1983), Outremer (1989), and many more. What makes Knott unique among our poets is that he made it extremely difficult even for his admirers to keep up with his work and have a clear idea of what he had actually accomplished as a poet, since he invariably quarreled with his publishers as soon as his books came out, allowing many of them thus to go out of print. To remedy that, he kept bringing out new volumes of poems in bound typescript editions, handing them out to people he knew or sneaking them into bookstores and leaving them on poetry shelves. Once the Internet came along, he posted new poems and old poems that he had tinkered with on his blog, gaining in the process many new readers and losing as many older ones. I imagine it’ll take years to sort all this out and have a book that represents his best work in all its amazing variety, from the early surrealist experiments to his sonnets and other poems in traditional forms. The day I heard that he had passed away, I was broken-hearted and kept thinking of him late into the night. At some point I got out of bed and went searching among my books till I found this old poem of his and heard his voice saying it as I sat down to read it:

Mother’s List of Names

My mother’s list of names today I take it in my hand

And I read the places she underlined William and Ann

The others are my brothers and sisters I know

I’m going to see them when I’m fully grownYes they’re waiting for me to join em and I will

Just over the top of that great big hill

Lies a green valley where their shouts of joy are fellowing

Save all but one can be seen there next a kinAnd a link is missing from their ringarosey dance

Think of the names she wrote down not just by chance

When she learned that a baby inside her was growing small

She placed that list inside the family BibleThen I was born and she died soon after

And I grew up sinful of questions I could not ask her

I did not know that she had left me the answer

Pressed between the holy pages with the happy laughter

Of John, Rudolph, Frank, Arthur, Paul

Pauline, Martha, Ann, Doris, Susan, you all,I did not even know you were alive

Till I read the Bible today for the first time in my life

And I found this list of names that might have been my own

You other me’s on the bright side of my moonMother and Daddy too have joined you in play

And I am coming to complete the circle of your day

I was a lonely child I never understood that you

Were waiting for me to find the truth and knowAnd I’ll make this one promise you want me to

I’m goin to continue my Bible study

Till I’m back inside the Body

With you