Hasn’t it all been done before? Perhaps better than anyone today could ever do it? If so, why read contemporary novels, especially when so many of the classics are available at knockdown prices and for the most part absolutely free as e-books? I just downloaded for free the original Italian of Ippolito Nievo’s Confessions of an Italian. It’s beautifully written. I’m learning a lot about eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Italy. It’s 860 pages long. A few more finds like that and my reading time will all be accounted for. Why go search out the difficult contemporary author?

As a reviewer of books she would often pan, Virginia Woolf thought one of the pleasures of reading contemporary novels was that they forced you to exercise your judgment. There was no received opinion about a book. You had to decide for yourself whether it was good. The reflection immediately poses an intriguing semantic puzzle; if, on reading a book, you enjoy it, then presumably it is good, at least as far as you are concerned. This is not something you have to “decide.” If you have to decide whether a book is good, does that mean you don’t know whether you enjoyed it or not, an odd state of affairs, or you don’t know whether your enjoyment or lack of enjoyment is an appropriate response?

This sounds rather complicated, yet we know perfectly well what Woolf is talking about. A new kind of book might offer pleasures we haven’t yet learned to enjoy and deny us pleasures we were expecting. Rather than fitting in with something we are long familiar with, it is asking us to change. And how many people are genuinely open to changing their taste? Why should they be? One of the curiosities of Joyce’s Ulysses is how many reviewers and intellectuals changed their positions on the book in the ten years following its publication. Many swung from hating it to admiring it—Jung comes to mind, and the influential Parisian reviewer Louis Gillet, who went from describing it as “indigestible” and “meaningless” to congratulating Joyce on having written the great masterpiece of his time. But many others turned from adulation to suspicion. Samuel Beckett went from believing that Joyce had brought the English language back to life to wondering whether actually he wasn’t simply pursuing the old error, as Beckett had come to see it, of imagining that language could ever evoke lived experience. Faced with something new, we may take a while to arrive at a settled response.

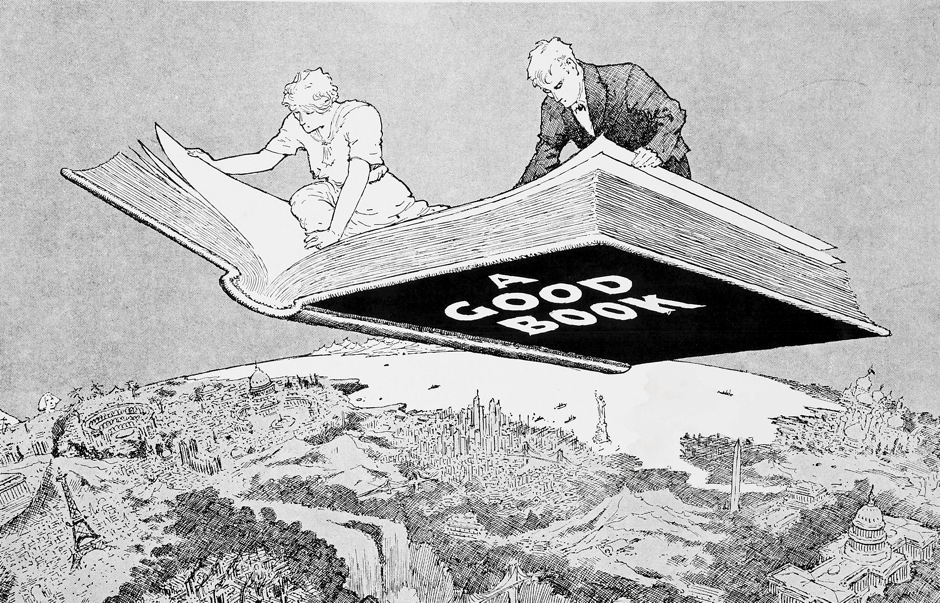

And this uncertainty of ours, as we tackle, say, our first Eggers, our first Pamuk, our first Jelinek, our first Ferrante, or as we switch from an early Roth to a late Roth, is actually part of the pleasure. And this pleasure in adjusting to the new—waiting to see if it will seduce us or bore us, understanding the nature of our readerly expectations precisely as they are challenged—can become addictive, or simply more interesting to us than the easier pleasure of finding yet another book pleasantly similar to others we have already enjoyed. Regardless of whether in the end we entirely enjoy a contemporary novel, we may nevertheless enjoy thinking about what is being asked of us. This was certainly my experience reading Murakami, Jelinek, and Saramago. I don’t greatly enjoy any of these writers. But I enjoyed grappling with them. Hence “it is even arguable,” as Woolf says, “that we get actually more from the living, although they may be much inferior, than from the dead.”

Objection: Isn’t there the same newness, or at least strangeness, when we tackle an older or foreign novel written in a tradition we’re not familiar with? The Tale of Genji, for example, or The Sorrows of Young Werther, or even Nievo’s Confessions of an Italian? There is, but with two important differences. A work like The Tale of Genji has already convinced millions of readers over centuries; I can go out on a limb and declare against it, but if I do so I’ll also have to ask myself why so many other people have enjoyed it over so many generations. More pertinently, the fact that I know nothing of eleventh-century Japan rather hampers me when I come to wondering whether this story is an appropriate response to the world the author lived in. When The Tale of Genji is strange to me it is likely because that world is strange to me, but not urgently so, since I don’t have to live in it myself.

Even when I read Nievo, despite having lived in Italy for thirty years and having read a few other Italian novels of the nineteenth century (not that many are in print), I really don’t know, intensely, what it was like being alive in Venice and Bologna and Milan in the early nineteenth century. I won’t react with the same engagement to Nievo’s take on the 1848 revolutions as I will to, say, Martin Amis’s account of life in 1980s London in London Fields. I could make all kinds of objections to Amis’s book, for the simple reason that I was there. And I can get very excited when he hits the nail on the head (as I see it). This won’t happen reading Fielding’s Tom Jones, where half the pleasure is: Wow, how different the world once was.

Advertisement

The excitement of tackling the new novel that dares to recount the contemporary scene is always galvanized by these questions: How is it that someone sharing my world wrote this book that I perhaps find strange and difficult? What is he trying to tell me about it, about the way I perceive it? Is it a useful difficulty? Could I, too, perhaps, react to our times in this way, and would it make sense if I did so? This was certainly the question readers faced when tackling Ulysses, but also Mrs. Dalloway, or A Farewell to Arms, or Beckett’s Trilogy, or The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum, or Gravity’s Rainbow, or DeLillo’s Underworld. And these are the books that eventually convinced sufficient numbers of readers to find a place for them in the public mind. Many others, equally fascinating to read at the time perhaps, have fallen away. B. S. Johnson comes to mind. Yet the pleasure of thinking about the work’s relation to the contemporary world was the same with Johnson as it was, say, with Beckett. And many were convinced for a while.

To read the Iliad, claims Roberto Calasso in The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, is to appreciate that there is no progress in art. It’s hard not to agree. But that does not mean that everything has been done. The world changes and people change and it is the way the author is sensitive to things as they are now that excites us in contemporary fiction. When I wrote my novel Cleaver in 2005, one of my European editors complained about my including text messages between the characters in the book. Old and unaccustomed to the mobile phone, he felt this was a gimmick. Eight years later, it is hard to imagine anyone objecting to the presence of text messages in a novel. To recount modern life one has to have characters with iPads and smart phones who take trains and planes, and to be aware how this alters consciousness, identity, and the kind of experiences people have. They are constantly exposed to contact from everyone they know and many they don’t.

In fact what becomes suspicious in a new novel is when it merely pastiches the effects of past novels, when it takes us back to a past the author doesn’t know except through books, so as to be able to repeat the pleasures of the books of the time. Which never are quite repeated. The pleasure of reading Nievo has to do with the fact that he really was in the fray of the Risorgimento and seeking to establish a position that made sense in the changed world he lived in. That gives the book its immediacy. To read Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard, written in the 1950s, is to read a charming and effective pastiche. It seems to spring mainly from the author’s determination to write a stylish and sophisticated novel, imagining the upheavals of the Risorgimento safe in the knowledge of hindsight, safe in the knowledge of how good traditional novels are written.

“Into thirty centuries born,” Edwin Muir began his most celebrated poem, “At home in them all but the very last.” Much is said about escapism in narrative and fiction. But perhaps the greatest escapism of all is to take refuge in the domesticity of the past, the home that history and literature become, avoiding the one moment of time in which we are not at home, yet have to live: the present.

This is the place of hope and fear,

And faith that comes when hope is lost;

Defeat and victory both are here.

In this place where all’s to be.