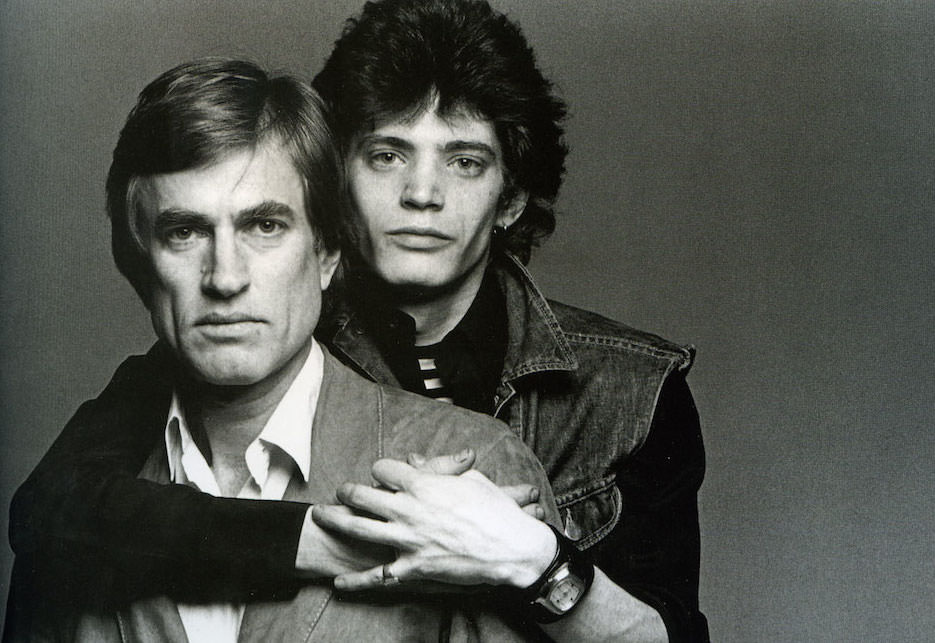

When I was an editor at House & Garden during the lush-budget 1980s, our PR department told me to have a new publicity shot taken by anyone I liked and have the bill sent to the magazine. My friend Duane Michals had done my earlier author photos, but in search of something different I contacted Robert Mapplethorpe, the forty-year-old enfant terrible who’d made a scandalous name for himself with his raw depictions of sadomasochistic gay sex. More to the point, I had been noticing his black-and-white portraits of people in the art world including Willem de Kooning, Leo Castelli, and Philip Johnson—some of the strongest and most flattering I’d ever seen—and wanted one of my own. Not only did Mapplethorpe instantly agree to photograph me, but offered what he called a professional discount—$10,000, instead of his standard $15,000 fee. I only recently learned that he usually charged $10,000 for his head shots, and merely pretended to give Condé Nast a cut rate.

However, on the day I was scheduled to be immortalized by Mapplethorpe—January 16, 1987—I opened The New York Times and saw an obituary for Sam Wagstaff, the sixty-five-year-old curator and collector who had been Mapplethorpe’s lover for a decade and a half as well as his most tireless promoter. Expecting the session to be cancelled, I called the photographer’s long-suffering assistant, Dimitri Levas, who said we were still on, although Robert might be somewhat delayed.

In the quarter century since Mapplethorpe’s death from AIDS, Wagstaff has remained relatively obscure to the general public, overshadowed by his protégé’s undimmed notoriety. But beyond launching Mapplethorpe’s career, he was a prescient curator of contemporary art, all-purpose tastemaker, and pioneering collector of photography. Now we are given a closer look at Wagstaff’s part in one of the most remarkable artist/patron relationships of the late twentieth century in Philip Gefter’s new biography, Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe.

The book suffers from much digressive padding (in a typically unnecessary detour we are told about the smell of patchouli oil wafting through New York’s East Village in the late 1960s) as well as one major disproportion: there is both too much about sex and not nearly enough about Wagstaff’s formative relations with the artists he championed, most notably Tony Smith and Agnes Martin. Yet despite some atrocious stretches of prose (although other parts are quite lyrical) Gefter delivers the most persuasive account yet of how Wagstaff encouraged a small coterie of likeminded collectors—many of them gay, and several of them my friends—who raised vintage photographs from quaint curiosities to a “serious” artistic medium. Mapplethorpe was the inadvertent catalyst of this historic shift.

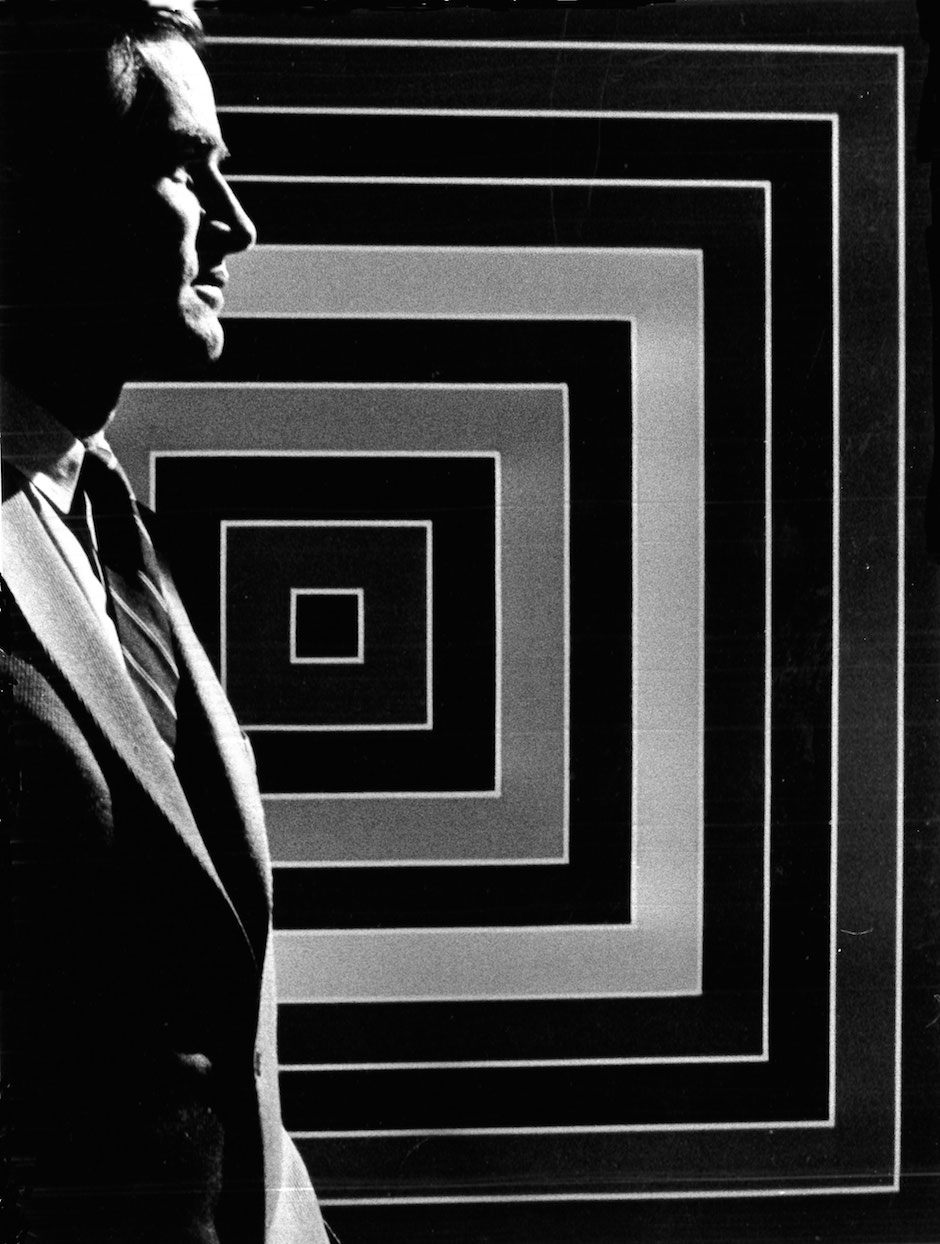

For most of the twentieth century, many questioned photography’s legitimate place among the fine arts, and the audience for even the greatest historical examples was limited to a few true believers. However, when Mapplethorpe dragged Wagstaff to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 1973 exhibition The Painterly Photograph: 1890-1914, Wagstaff had an epiphany. Gazing at Edward Steichen’s impressionistic 1904 views of Manhattan’s Flatiron Building, he became convinced that photography was an art form, not a mere mechanical process.

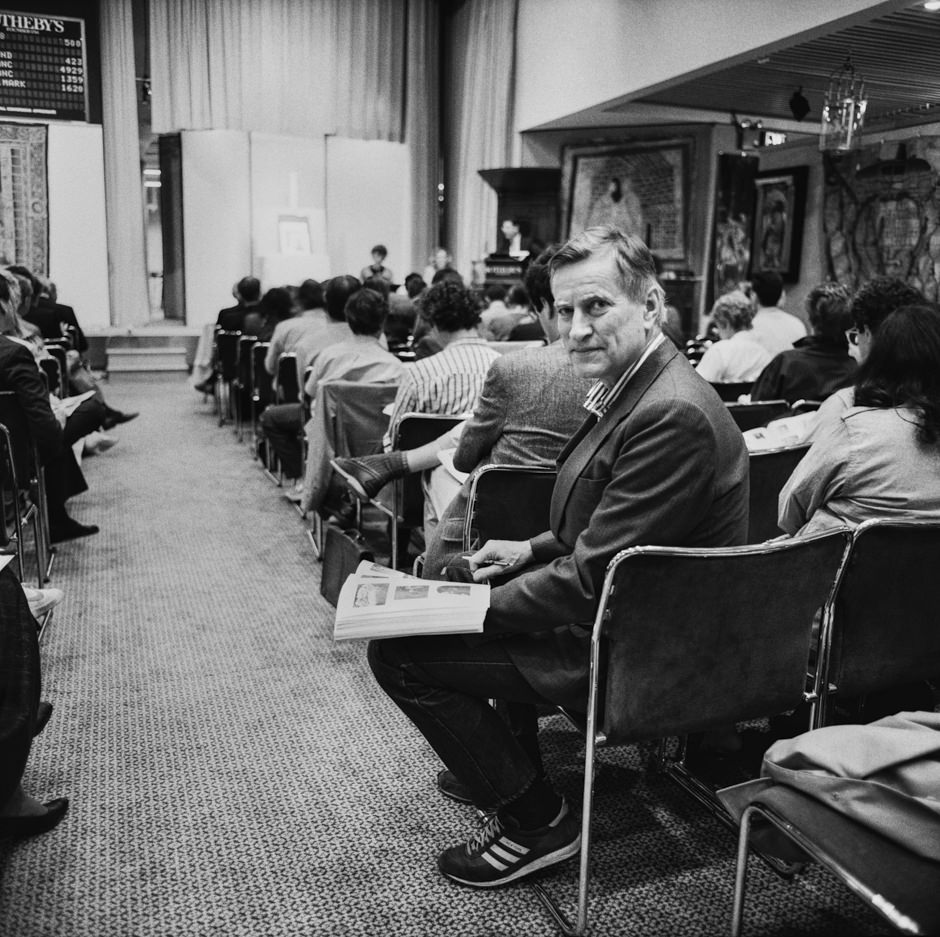

This revelation prompted a decade of frenzied acquisitions by Wagstaff, who came from an old New York family and used his substantial wealth to buy some of the most important photographs by dozens of forgotten early masters including Roger Fenton, Julia Margaret Cameron, Charles Marville, and his favorite, Gustave Le Gray. An indication of how successful he and his friends were is the extent to which these artists are now prominently featured in leading museums. Gefter’s extensive interviews with Wagstaff’s inner circle, among them Paul F. Walter (who specialized in nineteenth-century photographs), John C. Waddell (who favored interwar modernism), Pierre Apraxine (curator of the estimable Gilman Paper Company collection), and Daniel Wolf (whose 57th Street photography gallery was the best in America at the time) reveal how several of them worked in concert.

During the 1970s and 1980s, they attended the major photography sales in London together, did not bid against each other, and divvied up the spoils afterward, notwithstanding official prohibitions against such practices. Much of this seemed to have been orchestrated by the collector and former CIA agent Harry Lunn. Drawing on interviews with Clark Worswick, another member of Wagstaff’s group and on invoices in Wagstaff’s files showing shared lots, Gefter writes:

Advertisement

[Lunn] was known to gather the Wagstaff band of collectors and dealers for lunch during the auctions in London. “Harry’s idea was to get everybody so drunk that they wouldn’t bid against him,” Worswick said. “And he would share all the lots with his little group, and it would be impossible for anybody else to get anything.”

This kind of collusion kept prices down, Gefter notes, while the steady turnover they stimulated brought more and more fresh material out of family attics and into the salerooms as word spread that old photos were valuable. Rarely has the mechanism of creating a new and lucrative market in art been exposed so frankly and explained so fully.

Wagstaff’s leadership was bolstered by his extraordinary charisma, striking good looks (he was constantly likened to Gary Cooper), and limitless self-confidence in his artistic judgment, a combination his fellow travelers found irresistible. Above all there was his “eye”—arguably the finest of his generation—for discovering important art in neglected corners of the market.

Though well-educated (Hotchkiss, Yale, NYU Institute of Fine Arts) Wagstaff was no intellectual, and could be oddly inarticulate, as his sometimes childish scribblings indicate. Circumspect about his homosexuality for decades, he became more open with the onset of the sexual revolution. In 1972, when he noticed a fetching snapshot of Mapplethorpe, twenty-five years his junior, in the apartment of a mutual acquaintance he asked for his phone number. He began his first call by asking seductively, “Is this the shy pornographer?”

After he and Mapplethorpe (whom Wagstaff called by the WASPy endearments Muffin and Wumps) ended their physical affair in 1976, they remained close in all other ways. Eight years later, Wagstaff sold his collection of 2,500 masterworks of nineteenth- and twentieth-century photography to the J. Paul Getty Museum for $5 million and moved on to yet another undervalued medium with equal fervor: nineteenth-century silver. And it was this, I discovered, that had preoccupied Mapplethorpe on the day of my photo shoot, in the immediate aftermath of Wagstaff’s death from AIDS.

Minutes after I arrived at Mapplethorpe’s West 23rd Street studio, he entered carrying several large shopping bags bulging with silver he had just removed from Wagstaff’s penthouse at 1 Fifth Avenue. “I had to get there before Sam’s sister had the apartment sealed,” he explained with a wry smile. “You know, possession is nine tenths of the law.”

Mercenary as this seems, Mapplethorpe (who was Wagstaff’s principal heir) did exactly as his “Sammi” would have wanted. American Aesthetic Movement silver became Wagstaff’s last grand obsession, and the way it took over his emotional life—and nearly all of his living space—was a source of amazement to those who witnessed his almost erotic attraction to these objects, which he frequently caressed and sometimes even slept with.

Mapplethorpe, however, could not fathom what Wagstaff saw in the stuff, and after he unwrapped one or two pieces—I recall a Tiffany pitcher with repoussé chrysanthemums—he briskly announced, “Let’s get started.” For the next hour I stood bathed in the glow of two enormous floodlights while he snapped away, apparently unfazed by his mentor’s death. Whatever Mapplethorpe’s true feelings, Wagstaff was unequivocal. Shortly before he died, this passionate cultural force told Patti Smith (Mapplethorpe’s erstwhile girlfriend), “I have only loved three things in my life. Robert, my mother, and art.”

Philip Gefter’s Wagstaff Before and After Mapplethorpe: A Biography, has just been published by Liveright.