Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum has always been a place of surprises, despite its severe façade. Perhaps this has to do with its history, the coming together of two seventeenth-century institutions, the University Art Collection, stuffed with portraits of bewigged dons, and the sprawling cabinet of curiosities amassed by Elias Ashmole. The latter was based on the collection gathered by the Tradescants, father and son, famed gardeners and plant collectors, who put it on show at their Lambeth home as “Tradescant’s Ark,” allowing the ribs of a whale to share space with the hand of a mermaid, poisoned arrows, and agate goblets. Since the Ashmolean’s stunning extension was completed in 2009, walking up the curving staircases and circling through the galleries and across glass walkways feels like wandering through the whorls of a shell, mother of pearl, glowing with treasures. All of which has made it an absolutely fitting place for “William Blake: Apprentice and Master,” an exhibition that is at once didactic and very strange.

Entering the exhibition, with its low light and dark walls, is like opening another secret cabinet, whose curiosities defy time. This show, however, which has irritated visitors as much as entranced them, is determined to place the “timeless” genius back in his day, explaining how the development of his idiosyncratic techniques both sprang from and challenged contemporary art education and practices. A friend had declared that the opening rooms were “rather bossy.” And it’s true that I could almost feel the curator, Michael Phillips, decreeing that I must go slowly and be prepared to read a lot of labels. His opening catalog line is just as severe: “Nothing can tell us more about a work of art than the discovery of how it was made.” Hmmm. There’s clearly no point wailing “But where’s Blake?”—where’s the revolutionary spirit, the color-washed poet, the genius and madman?

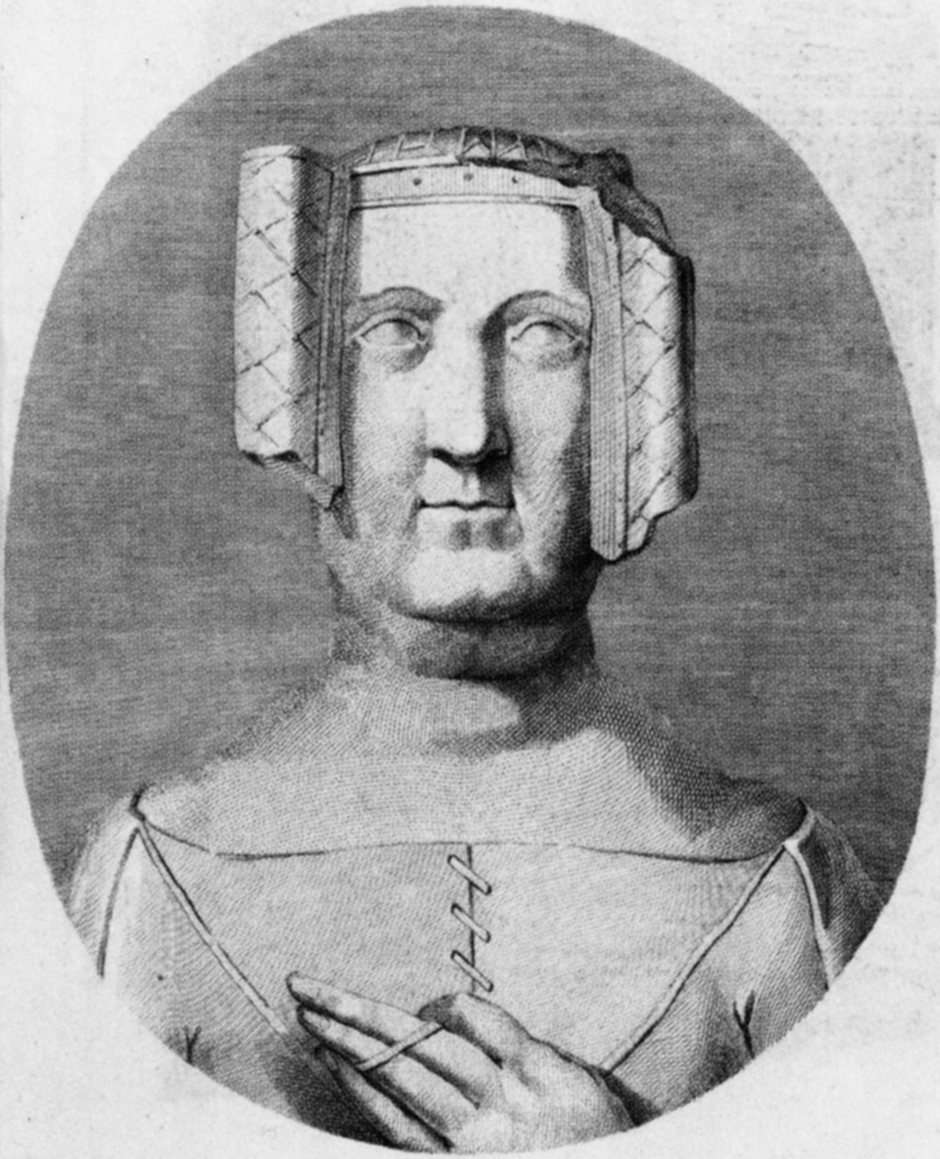

It raises questions about how to display an exhibition about craft without information overload. But that’s fine by me. I liked being flung back into the London of the 1770s, imagining Blake hovering around the print sales in Covent Garden, poring over Durer’s prints and Michelangelo’s drawings, or copying plaster casts to improve his draftsmanship. At fourteen he was apprenticed to the engraver Henry Basire, and two years later began drawing the monuments in Westminster Abbey, the start of a five-year immersion in the Gothic that would influence his own integration of text and image in his “illuminated printing.” It’s touching to see the entry in the Stationer’s Register, August 4, 1772, that begins this slow progress. Fascinating, too, to see early works, like the solid, sculptural engravings of royal effigies. They radiate a restrained energy, ready to break out.

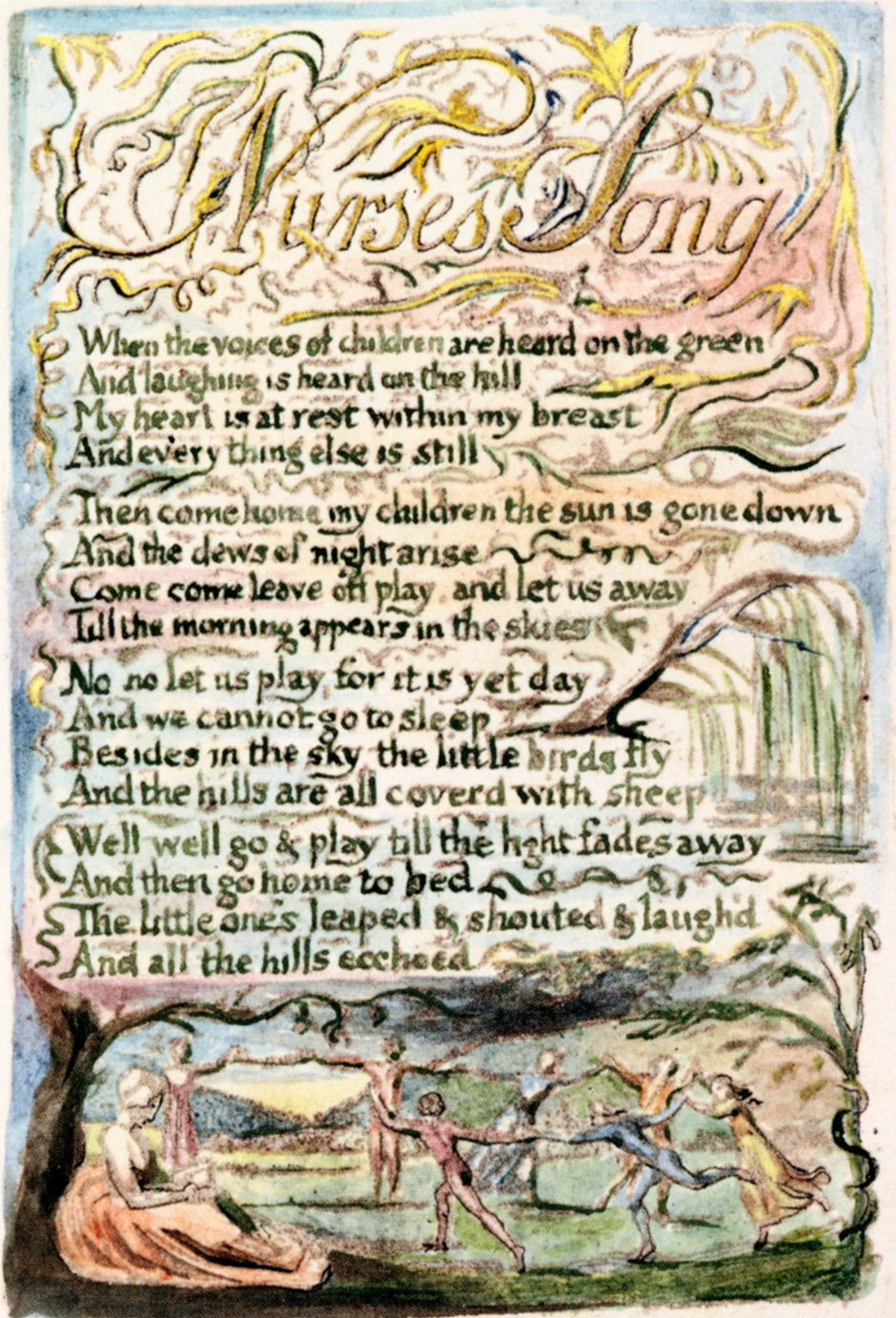

Then, suddenly, after he leaves the Royal Academy schools, we encounter the Blake we know, with the Poetical Sketches of 1783, his first independent publication, partly funded by his friend the sculptor, illustrator, and designer John Flaxman, with its printed sheets folded by Blake and his wife Catherine, stitched into blue-grey wrappers. From the start his verse shows the biblical knowledge and reading he later described in his inimitable style: “Milton lov’d me in childhood & shew’d me his face. Ezra came with Isaiah the Prophet, but Shakespeare in riper years gave me his hand.” Tumbling onward, here is the manuscript, heavily corrected, of the satire An Island in the Moon (1784-87), with the drafts of three songs that would soon be included, in a revised version, in Songs of Innocence, and a sheet showing his attempts at the mirror writing he would need for his illuminated books. These are just over the horizon, and one can’t help but gasp at the poems “Holy Thursday” and “Nurses Song,” springing to pale life, the etchings printed in brown leaf and haloed with watercolor, with the children in the “Nurses Song” dancing in a circle below:

When the voices of children are heard on the green

And laughing is heard on the hill

My heart is at rest within my breast

And everything else is still

Applied to Blake, the word “visionary” is a term of method as well as perception. After his younger brother Robert died in 1787, his spirit specifically directed Blake, as Robert’s friend J.T. Smith recorded, “in the way in which he ought to proceed.” This was to write his poetry and draw the marginal embellishments in outline directly on to the copper-plate “with an impervious liquid,” then to eat away the remaining parts, so that the outlines remained, and could be painted “in any tint he wished.” This adaptation of relief etching, “printing in the infernal method” as Blake himself called it, gave him freedom to etch his poetry and design directly on the plate and print it on his own rolling press. We can follow the experimental process in his print of Robert’s own drawing, the ominously titled The Approach of Doom, from pen and ink and sepia wash, to relief and white-line etching. But then we are with Blake alone, in the beautiful plates for the Book of Thel and Songs of Innocence, and his series All Religions are One, where his voice sounds out: “There is No Natural religion,” and “The desires & perceptions of man untaught by anything but organs of sense, must be limited to objects of sense.”

Advertisement

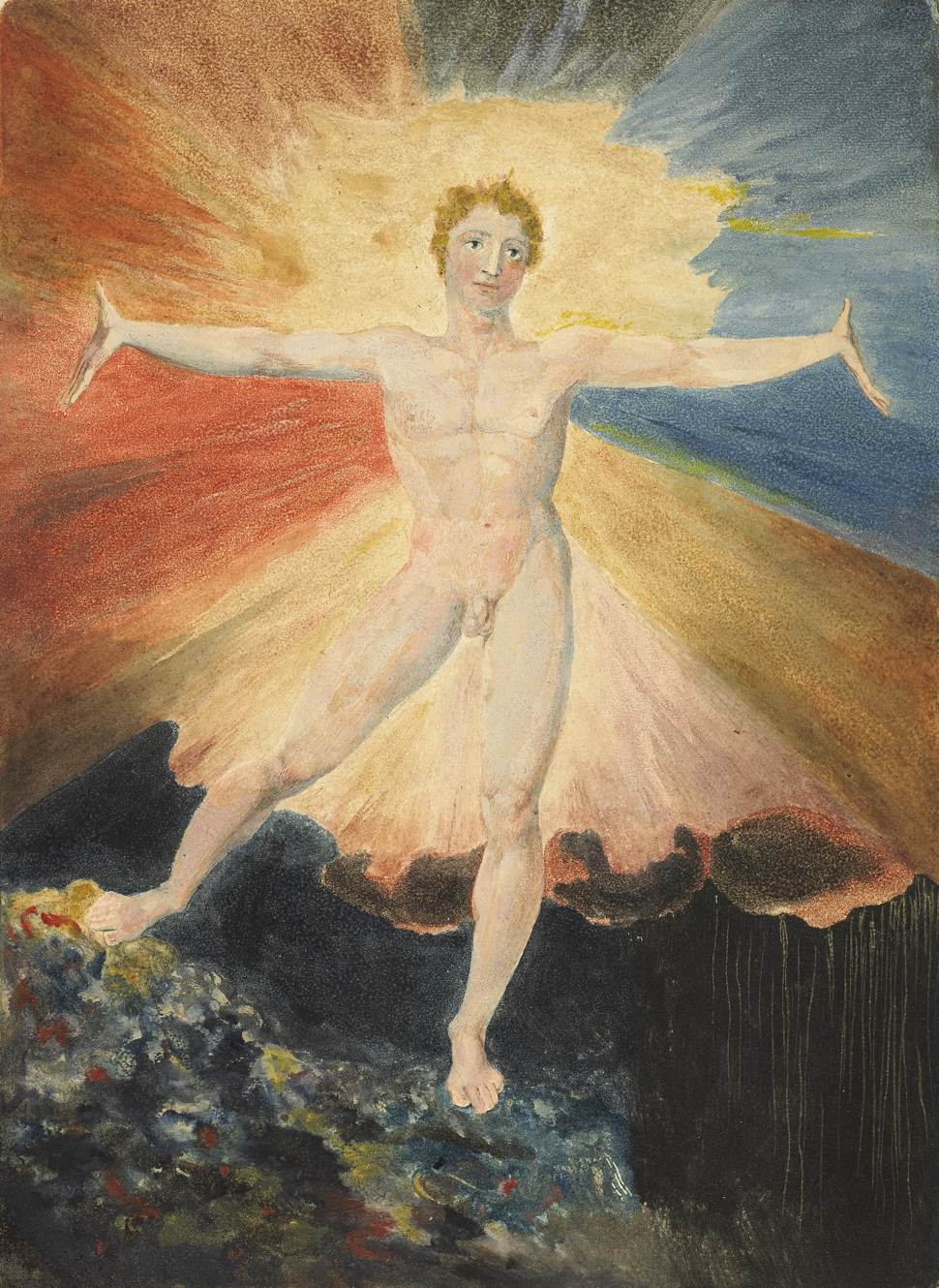

By now, the viewer is being asked to do two things at once, to follow both the slow stages of Blake’s developing technique and the galloping advance of his ideas and rhetoric. It’s a lot to take in, leaving little room for the powerful response and questioning that Blake’s works usually provoke. Yet that is called out by the startling plates for Europe, a Prophecy, and the large color prints of 1795—Nebuchadnezzar, Newton, The House of Death, and The Dance of Albion, works that never fail to amaze. Their various states bring painter and printer together, as Blake works with his fine brush, then applies sweeping areas of glue-based color pigment. Once they are printed, he returns to pen and ink to define the images, adding watercolor glazes. These remain a wonder, and, as Phillips writes, “To this day the Large Colour Prints have never been entirely understood—either in terms of the techniques and materials used to produce them or in how they were to be understood, either individually or together.”

It feels right to end in mystery. The exhibition left me dazed by the technical detail but aware that I would never look at a Blake work in the same way again. After all this I was unexpectedly moved by the coda on his legacy, which takes us from the tiny woodcuts for Virgil’s Georgics to the Blake-inspired artists who called themselves the Ancients and the pastoral moonlight of Samuel Palmer.

I have one lament. The exhibition is so brave in its focus on the technical that it’s a distraction to find a recreation of Blake’s tiny London studio in the wonderfully named Hercules Buildings. Is this intended to draw people in? It seems a blunder to place this empty, clean, National Trust-like reconstruction amid prints that imply color, clutter, and mess, piles of proofs, the smell of ink and glue and paint. True, we can see how strong the 5’4” Blake must have been to work the heavy oak press, but his art demanded a different kind of strength. His great prints leave the workshop world behind, their figures soaring and stretching and circling into the stratosphere of Blake’s ecstatic, terrible, fourfold vision. In his technique, in his genius unacknowledged in his time, and in his ambition and desire, contraries unite and matter and spirit meet.

“William Blake: Apprentice and Master,” is on view at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford through March 1.