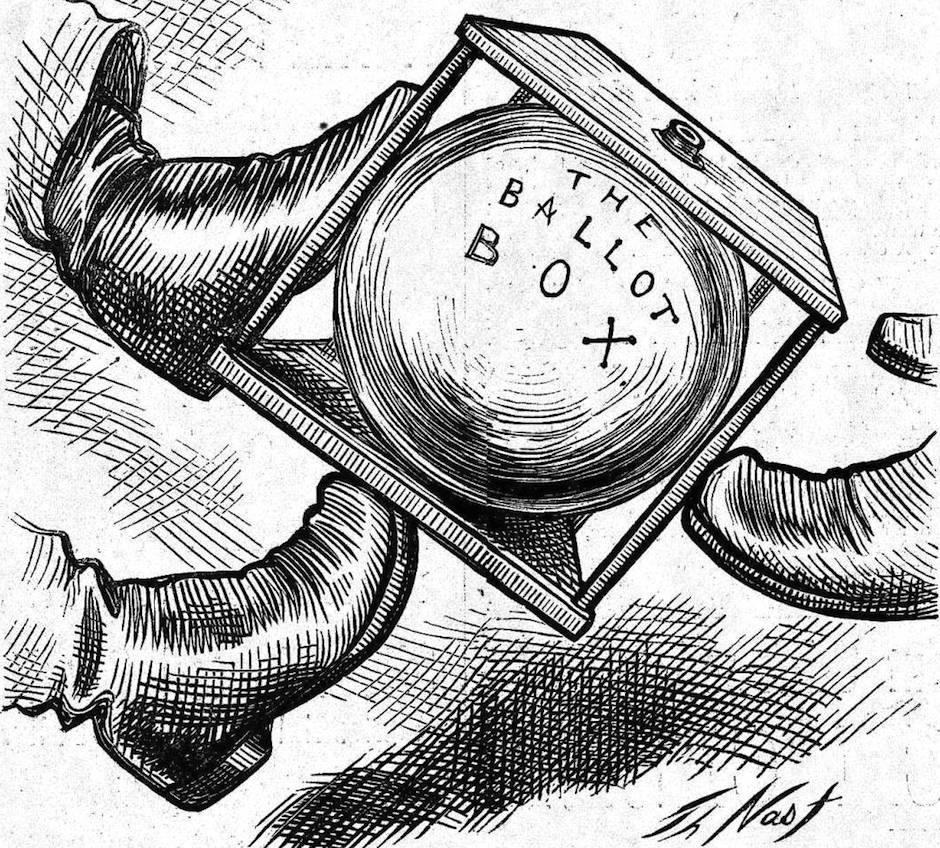

Five years ago this week, in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, the Supreme Court decided to allow unlimited amounts of corporate spending in political campaigns. How important was that decision? At the time, some said criticism of the decision was overblown, and that fears that it would give outsize influence to powerful interests were unfounded. Now, the evidence is in, and the results are devastating.

To coincide with the decision’s fifth anniversary, eight public interest organizations—the Brennan Center for Justice, Common Cause, Public Citizen, Demos, US PIRG, Public Campaign, Justice at Stake, and the Center for Media and Democracy—have simultaneously issued reports that demonstrate the steadily growing influence of money on elections since the Court’s decision. Their findings show that the case opened the spigot to well more than a billion dollars in unrestricted outside spending on political campaigns, by corporations and individuals alike. It has done so at a time when wealth and income disparities in the United States are at their highest levels since 1928. Increasingly, it’s not clear that your vote matters unless you’re also willing to spend tens of thousands of dollars to support your preferences.

Some of this money has come directly from the kind of corporate money at issue in Citizens United. But much more of it has come from other kinds of funding made possible by the Court’s decision, whose rationale undermined expenditure limits across the board, not just for corporations. Take the 2014 midterm elections. Just eleven closely contested Senate races tipped the balance and allowed the Republicans to regain control of the Senate for the first time since 2006. In eight of the ten states for which data is available, outside groups outspent the candidates themselves, by many millions of dollars. In North Carolina, for example, outside groups spent $26 million more than the candidates did. With these kinds of numbers, elected politicians may feel as beholden to such groups as to the people who actually voted for them.

Much of the newly unrestricted funding came from so-called “super PACs,” political action committees that raise money exclusively for “independent expenditures,” usually television and radio advertisements. Citizens United did not itself involve super PACs, but the decision had the effect of freeing super PACs from any meaningful constraints. The Court ruled that the government has no legitimate interest in restricting “independent expenditures”—as opposed to contributions to candidates—because in its view, only contributions have the potential to corrupt candidates. Two months later, in March 2010, a federal court of appeals relied on that rationale to strike down all limits on how much individuals may give to super PACs, since they are organized exclusively for the purpose of “independent expenditures.”

According to the Brennan Center report, over the five years since these decisions, super PACs have spent more than one billion dollars on federal election campaigns. And because these organizations are free of any limits, they have proved to be magnets for those who have the resources to spend lavishly to further their interests. About 60 percent of that billion dollars has come from just 195 people. Those 195 individuals have only one vote each, but does anyone believe that their combined expenditure of over $600 million does not give them disproportionate influence on the politicians they have supported? The average contributions of those who give more than $200 to such super PACs are in the five- and six-figure range. The average donation over $200 to the ironically named Ending Spending, a conservative PAC, was $502,188. This is a game played by, and for, the wealthy.

It is also a natural consequence of the Supreme Court’s faulty logic in Citizens United and related cases. The Court has found that contributions to candidates can be restricted because they pose the risk of quid pro quo corruption—when a representative essentially sells his vote to the highest donor. But according to the Court, expenditures made independently, even if they advocate a particular candidate’s election, don’t pose that risk, and therefore can’t be limited. This makes little sense. If I give $500,000 to Harry Reid for his reelection, most of which he will probably spend on television ads, there’s indeed a danger that he may feel indebted to me in a way that undermines democracy. So I can’t do that. The most I can donate is $2,600 per election. But under the Court’s logic, I am free to spend $500,000 on my own television ads advocating Reid’s reelection.

The Court’s doubtful rationale rests on the notion that these expenditures are “independent,” but that, too, is an illusion. Increasingly, super PACs focus entirely on the election of a single candidate, and are often run by the candidate’s former staff. Nearly half of all super PACs spending $100,000 or more in 2014 were devoted to the election of a single candidate. Because they are technically independent and engage only in expenditures, they provide an end run around contribution limits. Donors who have made the maximum contributions allowed by law to a single candidate can legally give unlimited amounts to these single-candidate PACs—rendering the limits on direct contributions largely meaningless. Six supporters of Senate candidate Greg Orman, for example, created a super PAC one month before the 2014 election and used it to spend nearly four million dollars in Orman’s support by election day.

Advertisement

The domination of electoral politics by the super-wealthy and the growing irrelevance of campaign spending limits have real-world consequences, because, as F. Scott Fitzgerald noted, the “very rich … are different from you and me.” A recent report by Demos chronicles how big money reinforces racial inequity. The rich are of course disproportionately white, and the poor are disproportionately black and Latino. The more influence that money has in electoral politics, the less influence racial minorities have. Common Cause’s report has similar findings, noting how large financial contributions have skewed the politics around several issues favored by a majority of voters, but not by big business and the wealthy, including minimum wage, climate change, and student loans.

These developments, it should be said, are not consequences of Citizens United alone. The problems with the Court’s campaign finance jurisprudence predated that decision. But in Citizens United, the Court reversed earlier precedent that had acknowledged a legitimate government interest in limiting the outsized influence of large sums of money on the electoral process. And this interest had been held to be legitimate even when the money in question did not present a direct risk of bribery or quid pro quo corruption. As I argued in a recent review of Zephyr Teachout’s Corruption in America, the problem with Citizens United was not that it recognized that corporations have speech rights, or that restrictions on money spent for political campaigns should be viewed skeptically as regulations of speech, but that the Court rejected any rationale for regulation other than avoiding quid pro quo corruption in the narrowest sense. The reports released last week underscore how much our democracy is paying for the Court’s flawed analysis.

So what can be done? As a formal matter, the only way for the people or their representatives to overturn Citizens United directly would be to amend the Constitution, a virtually impossible task. But even absent a formal amendment, the Court does not necessarily have the last word. Other constitutional decisions have sparked public controversy and later been overturned—among them Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld segregation, and Bowers v. Hardwick, which permitted criminal prohibitions on homosexual sex. Those decisions were not reversed simply because the Court changed its mind, but because groups of citizens engaged in a long and arduous campaign of education and advocacy to achieve that result.

Such a campaign is, thankfully, now underway to have the Court overturn or limit Citizens United. It has the support of retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens; many current and former members of Congress, who know first-hand the ills of big money; a large swath of the public, who view Citizens United as an undeserved gift to those who already have far more power and influence than they deserve; and a considerable portion of civil society, including the eight groups whose reports were issued last week. We are likely to see a tenth anniversary of the decision before we see any action in this regard. But if we are to preserve more than a semblance of democracy, it is essential that we convince the Court to recognize the urgent and legitimate need for robust limits on campaign spending.