If only the word “bibelot” had been a diminutive of “biblio-,” book, instead of a cognate of “bauble,” then I could have described Looking at Pictures as an ideal bibelot, a robust little hardback to slip into the pocket and take out to read in the elevator, say, without spoiling the line of the suit: well-printed, on stout, almost stiff, paper, copiously illustrated with well-colored and surprisingly assertive plates of paintings by Fragonard, Bruegel, Cézanne, and others, all glued down in the old manner like stamps and no bigger than postcards.

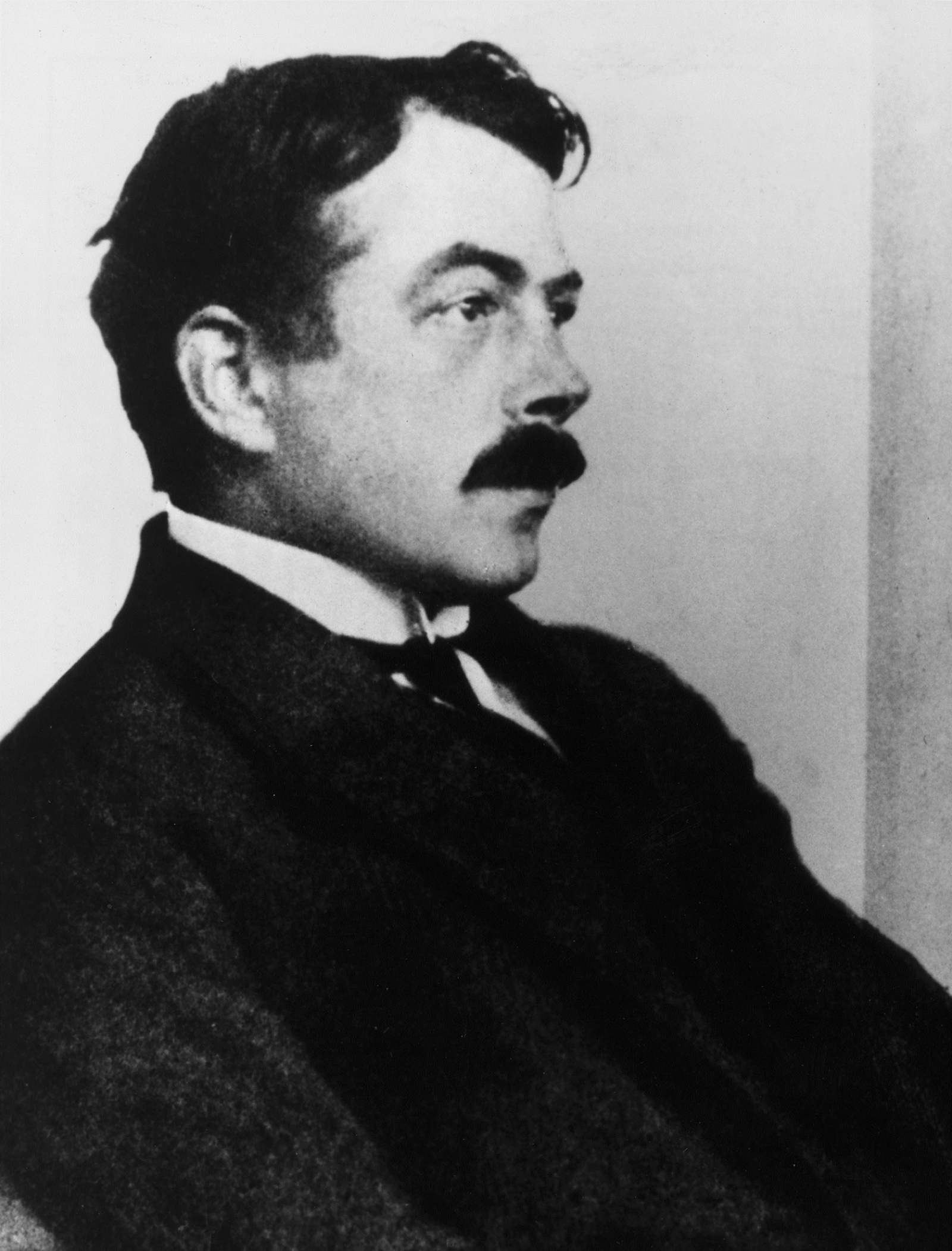

And so I would have paid a little homage to the Swiss genius and eccentric Robert Walser (1878–1956), who adored diminutives and kept himself alive—going everywhere on foot, and starving—by the writing and selling of his small prose pieces called feuilletons, or “little leaves.” “Worklet,” he describes one of the productions here, and another, “a tiny, infinitesimally small little essaylet.” Reaching the end of his sanity in the late 1920s, he further withdrew into something called his Bleistiftgebiet, his pencil terroir, writing on rejection slips and the like minuscule and perfectly illegible marks in perishable graphite (which, industrially magnified and magisterially deciphered, have now filled six further volumes, in addition to the twenty of his other works, all published by the canonical German firm of Suhrkamp). It was his way of taking himself off the books. As it is, then, I will call Looking at Pictures just an adorable bookling, and urge anyone with any tenderness in their soul to go out and buy one or two.

It consists of the selected art writings of Robert Walser. If there is something slightly starchy and preposterous-sounding about the prospect, then so there should be: anything by Walser should give a lift to the eyebrow and a smile to the lips. Like all his writing, it is both scripted—pedantically correct, ornate, mannerly, even a little pompous—to the point of artifice, and alarmingly liable to find in such a condition a source of endless amusement. Look at me walking on my hind legs, it seems to say. And then: Oh well, never mind.

Walter Benjamin talks of Walser’s “neglect of style,” which has an odd ring to it, given that Walser is incapable of writing a gray, functional sentence that merely gets on with the job, but perhaps it’s style as master that he means. In Walser you get style as instability or plurality, style as servant or passerby, volatile, huffy style, style as djinn, style that flies off the handle. Perhaps that counts as “neglect of style.” Walser writes with the excitement of an Englishman in a western, or of Molière’s bourgeois gentilhomme Monsieur Jourdain, having just been informed that he’s been speaking prose all his life. This is to some extent a Swiss propensity—to a native speaker of Schwyzerdütsch, High German or written German has an inherently risible aspect, “statues talking like a book,” to quote Randall Jarrell on some quite different matter—but Walser’s written German takes this distinction to a personal extreme.

Everything is performance, even nonperformance. A review of an exhibition of Belgian art in Bern is raised to a diplomatic-historical level, a suave episode in Swiss-Belgian, or better Helvetico-Burgundian, relations, as Walser bows himself out:

Pleased as I am to have had the opportunity to speak about a stately and beautiful artistic event, I consider myself obliged to limit myself with regard to the extensiveness of my remarks. Everything I have neglected to say can be given voice to by others.

Two small countries, the Republic of Modesty and the Kingdom of Politesse, are left circling each other in a Schneckentanz, a snails’ dance. Make no mistake, though: Susan Bernofsky, at work on a biography of Walser, and the translator of three of his four novels and a selection of his Microscripts (she took up the baton from the poet and essayist Christopher Middleton, who died last year and was Walser’s first translator, not just into English, but anywhere, which is a rare accolade for English), has done a wonderful thing here.

English has always preferred its foreign prose imports to be either realist novels or Saturday Evening Post–type short stories. Very short or very long stories—the dread novella—have always been notoriously difficult to place, as have oddities. Kafka the author of the brisk Metamorphosis is preferred (by miles!) to the author of the parables or the lamentably unfinished novels. Writings classified merely as Prosa on their German title pages almost need not apply; collections with names like Kleine Dichtungen (short poetic compositions—Walser published one such in 1914) are unthinkable. Walser, whose first publications were poems, and whose first book was a collection of quasi-schoolboy “essays,” Fritz Kochers Aufsätze in 1904, did indeed publish three quite proper novels in short order, Geschwister Tanner, Der Gehülfe, and Jakob von Gunten (in 1907, 1908, and 1909). The second of these, The Assistant, about a fellow who turns up to work in the household of a Swiss inventor, would be on any list of my favorite novels.1

Advertisement

It’s not as though the form defeated him—in 1925 he wrote, in microscript, a much stranger fourth, Der Räuber (The Robber),2 which remained unpublished in his lifetime—but lack of commercial success served to discourage his personally well-disposed publisher Bruno Cassirer, and winnowed his already slight readership. The ethical and congenial form for him, he decided, was short prose. “I crossed over in the past from book-composition to prose-piece writing because huge epic connections had begun, as it were, to get on my nerves,” Walser puts it. Or “It’s still not so long ago that I had an urge sometimes to roar.” Or again “During this performance several people walked out.” A piece may begin “Usually I first put on a prose piece jacket,” or “I am, by birth, a child of my country, by trade I am poor, my social status is that of human being, my character that of a young man, and by profession I am the author of the present autobiographical sketch.”

This is all indescribably lovely, moody, gallant, cracked, indomitable writing. It also asks to be very carefully selected and presented in an English that is emerging—maybe—from its mercantilist outlook, which likes to feel the thickness of any given entertainment between finger and thumb. Looking at Pictures is a new and beautifully focused collection of twenty-five pieces: a bouquet as much as a book. Art proves simply a wonderful “in” to Walser. It takes one straight to his free fancy, his shy elitism, his desire for drama, his absurdity, his unmanageability, his delight in objects, his courtly, unsleeping interest in the fair sex. (A lot of the pictures he writes about are pictures of or with women, while even in an account of a landscape, a lake is described as lying “spread out like silk, like a lady’s garment of the most decorous translucence.”)

Walser always thought and felt about art. His next older brother (Robert was the youngest boy of six, and there were two girls as well, one older than him, one younger), Karl (1877–1943), was a fashionable and gifted painter, muralist, illustrator, and set designer for Max Reinhardt and others. His idiom was applied art, his graphic style somewhere between caricature and naive. (Which is perhaps true of both brothers. Karl provided sympathetic illustrations for many of Robert’s books; his cover designs for Der Gehülfe and Die Rose are enchantingly winsome.)

They were close. Walser followed Karl to Berlin in 1905 (“the intoxicating gleam of the dark, metropolitan streets, the lights, the people, my brother. I myself, living in my brother’s apartment”); was launched by him into Berlin society (“Once I set foot in a gathering of at least forty full-blooded celebrities. Just imagine how glorious that was!”); and in 1906 he served briefly as secretary to the Berlin Secession, a cooperative organization of painters and collectors. But Walser was really no more suited to such employment than Rilke was, at exactly the same time, to working for Rodin: “A stately successor soon reduced me to a predecessor and provided me with an occasion to lay down my post, resign my position, delicately make way, and charmingly busy myself elsewhere” (this quoted from a hilarious and doleful piece called “The Secretary,” included in Berlin Stories).

Because painting and drawing were not writing, they drew Walser irresistibly; writing of course drew him as well. Still, the first move should be away, and he liked indirection, obliquity, the pace back or to the side. He wrote often of Karl and Karl’s life, both openly and explicitly and with a sort of veiled intimation of knowledge. Here was someone it was both easy and impossible to imagine himself being, Mastroianni to Robert’s Fellini.

At least three of the pieces in Looking at Pictures concern themselves explicitly with works by Karl Walser. The first, called “A Painter,” the earliest and longest item in the book, is in many ways a cornerstone for the rest. Walser ventriloquizes for his brother, the painter, who is “the author” of the piece (“These pages from a painter’s notebook chanced to fall into my hands, as the saying goes”). The movement—a sideways slippage—from writing to painting to writing, and the identification of economic and power relations as they apply in painting, both seem to delight the author. As often in Walser, a picture seeds words, seeds speech. The painter writes. The change of terrain means he loses caste, loses form, loses professionalism, in a way that was bound to appeal to the antiprofessional writer Walser.

Advertisement

The painter writes, as he declares,

for my own amusement, snatching a moment here and there from my painting, like a thief or some sort of scoundrel; I’ve always been fond of pranks. And what an innocuous, insignificant prank it is to write all these things down!

The delighted writer merely eavesdrops on him. A whole chain of transactions, a grand and semiscandalous romantic history, plays itself out before his merry ears. The painter lives in a villa, a villa belonging to a countess. He has himself a cozy little feudal set-up. He is a pet of the better class. “No,” he says, “I belong entirely to my Countess.” She is his patroness, his model, his landlady, his audience. “The Countess takes ever greater delight in my pictures,” he boasts. She watches him paint; she becomes, a little surprisingly, a backdrop to his art (one might have expected a frontdrop).

“A splendid, stalwart woman”—typical Walser diction, striking sparks from dead words. Sometimes a poet turns up. He is outclassed. A poor wretch. “Colors and lines have a sweeter way of telling their stories.” The painter paints, somewhat anxiously, a portrait of the Countess. “Well, I’m sure I’ll manage it.” In the end he does, and lo, it’s a success. “She stood for a long time before the completed object, saying nothing, but afterward she silently and with emotion held out her hand to me.”

Finally—as had to happen—the Countess falls in love with the painter. He—perversely—goes on writing. She has her way with him. “I am all adream, awhirl…. I have forgotten Art: poor art, thrust to the side.” Not long after, painting reasserts itself. “Yes, I love art more powerfully than I love the Countess.” Anyway:

Loving an artist promises very little, and in particular: no happiness. But what is happiness? It is, I believe, a sustained sense of well-being. But well-being is something that artists never feel, or only seldom.

In his lightsome, parodic way, Walser gives us the struggles of the just-past nineteenth century, the progressive French dix-neuvième of maudit and bohémien and épater le bourgeois, and its baggage of synesthesia and decadence and disorder of the senses: a spicy drama about art and society. He gives us his brother, never more powerful than when—deaf to his countess, deaf to his art—he is writing, never less powerful.

To Walser there are as many ways of writing about pictures as there are pictures. Perhaps far more. Sometimes, as with “A Painter,” the pieces come out resembling stories. Sometimes, like “An Exhibition of Belgian Art,” they are quite like actual reviews, only hopelessly distractible, wool-gathering ones that report on café and cloakroom (“Hats and coats reposed quietly upon and about the coatrack with a self-satisfied air”), and throw in scraps of autobiography or faux autobiography, and a learned historical excursus on the fifteenth century. (The effect is somehow both fluent and collage-like; you begin to see where John Ashbery, who blurbs the book (“Incredibly interesting and beautiful”), might have got his poems from.)

Finally, halfway down the third page (and bang in the middle of a paragraph), Walser remembers himself: “But when shall I start talking about art?” It’s really not style he disdains, so much as function or utility. Sometimes it seems the only piece Walser is interested in writing is the unpublishable one that will get him sacked; his discipline is the inverse of discipline.

At the same time it would be a mistake to think Walser is merely foolish and improvisational; he runs the gamut from nonsense to sense, from the most amblingly extensive to the most intensive and concentrated. A lot of the thought in his pieces is not only recognizably, even unmistakably, his thought, it is good thought: in praise of failure (“I find it sweet to seek the favor of a beloved, a person one admires, without this endeavor’s being crowned with success”); against excessive cleverness in artists (“Not everything needs to be puzzled out…. What is fitting is to trust in ourselves and the world”); a repeated assertion of nature’s (and art’s) “coldness.”

Some of the pieces even get around to describing paintings, but the descriptions themselves are wonderfully unreliable. (One of Walser’s many freedoms, it seems, is the freedom from description.) So in Rembrandt’s Saul and David the two are not looking at each other as Walser says they are, nor do they hold their respective spear and harp in clenched fists. The “skirt” of Van Gogh’s L’Arlésienne is not visible. There is no “lake” in Ferdinand Hodler’s Beech Forest. Bruegel’s Parable of the Blind is not a night painting, nor does it show “blind wanderers who have come to such violent blows on a village road that they must have made quite a racket.”

It also seems highly improbable that Fragonard’s The Stolen Kiss shows the lady of the house with a kitchen lad—just that that’s where Walser, below-stairs dreamer and mildest of social revolutionaries, pitched many of his apparently harmless fantasies. (The undesirable woman is a conundrum for Walser, who is troubled by the plainness of Mme Cézanne and the woman from Arles: “Also I’ve heard people say that he painted her several times.”) There’s a tendency in him either to animate his subjects or to take them off the walls and witness them as though they were actual scenes. “From his pictures,” he writes of Watteau, “one can hear at times tinkling bells, at times rustling leaves.”

Other works generate speeches, four paragraphs of what “the music of David’s harp seems to be saying” in Saul and David, even entire playlets. Walser absolutizes or relativizes, to taste. “Sensibility,” he says, “makes us small.” He is not afraid to admit, for instance, that his sense of a Cranach painting derives from a reproduction he had in his room, and which his outraged landlady took down, though later she mended his pants for him; or that he has never seen an original work by a particular artist who interests him (Fragonard). How different that is from Rilke, who, staying at Herta Koenig’s flat in Munich in 1915, found himself sharing the place with Picasso’s Saltimbanques, and held that ownership was really the only way to know a painting.

Walser puts himself squarely into his brother’s painting The Dream, of a delicate harlequin-like figure in white crossing a hump-backed bridge at the side of a much larger woman in lacy pink:

On my head, I wore a dainty dunce’s cap. My lips were red as roses, my hair a golden yellow that curled about my narrow temples in graceful ringlets. I had no body, or had one only barely. From my blue eyes, innocence gazed. I would so have loved to smile a beautiful smile; but this smile was too delicate, so delicate I couldn’t smile it, I could only think it, feel it. An enormous woman led me by the hand. Every woman is large when tender sentiments fill her, and the man who enjoys her love is always small. Love increases my stature; and being loved and desired makes me small. So now, dear, gracious reader, I was so diminutive and small that I could comfortably have slipped into the soft muff of my tall, dear, sweet woman.

Not only are things presented as though real, they are given reasonable and serious-seeming grounds for being the way they are: the impossible smile, the enormous woman, the somehow infantile but distinctly erotic-sounding desire. It’s a dream of smallness and submission, not a million miles away from the work of the Pole Bruno Schulz—although Schulz drew his own pictures.

Perhaps pleasantness is the ultimate taboo. Walser gives you blank irony—or is it praise of public art?

It’s my humble opinion that one does well to be respectful when approaching a work of art commissioned from an artist by the municipality or state and erected upon this or that public square.

(This appears en passant, and on the way to the exhibition he is writing about, on a frankly weird statue of the Swiss airman Oskar Bider, in Bern.)

He draws up strings of positive abstract sayings, not just as if they meant something, but as if they were the delectable flavors on the chart in a box of chocolates:

A variety of straying would seem to be the subject of the picture I am observing here, which appears to have been painted with exceptional delicacy, caution, precision, intelligence and melodiousness.

Morality, or innocence, keeps sticking its nose over the fence and opining: “Every great painter the world has known has been cheerful, quiet, thoughtful, clever and superbly educated.” The possible statement is the same as the impossible statement. Sarcasm or playing dumb or even—even—meaning it? Do you say “Doh!” or “You know, he’s right!”

Perhaps the ultimate irony is Walser’s admission that everything artistic or intellectual—“the mind which is also flesh,” says Robert Lowell—is physical in origin and by manufacture. “He has a hand to direct the brush according to the commands of his seeing and feeling eye,” it says in “A Painter.” And of Cézanne, in the last words of this exotic and lovely book: “One could justly insist that he made the most extensive use, bordering on the inexhaustible, of the suppleness and the compliance of his hands.” Walser had beautiful handwriting and, it was often noted, large, beautifully formed hands.

-

1

See Christian Caryl’s review in these pages, February 11, 2010. ↩

-

2

See J.M. Coetzee’s review of The Robber and Jakob von Gunten in these pages, November 2, 2000. ↩