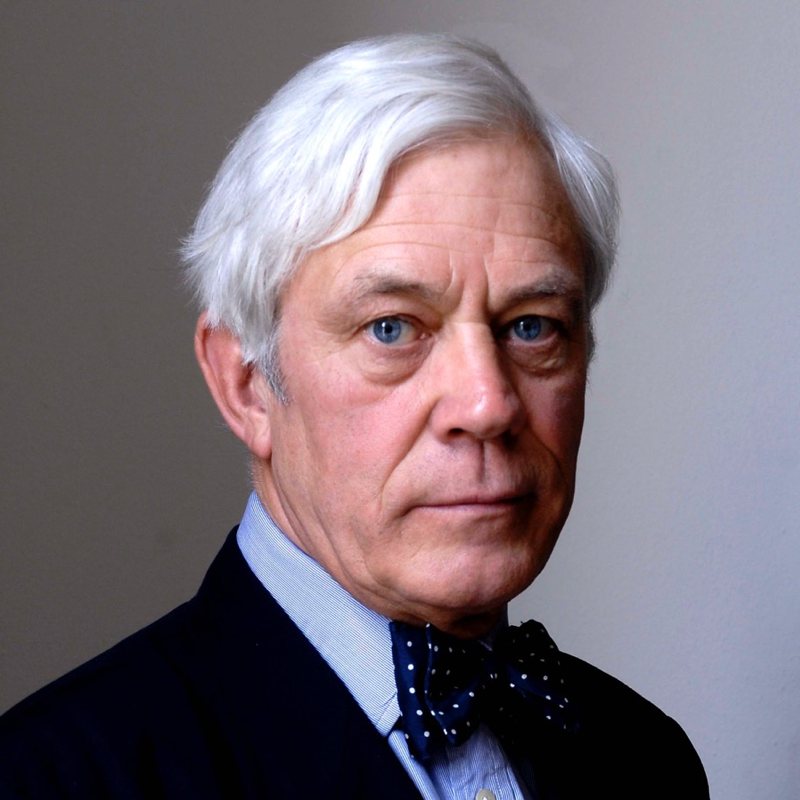

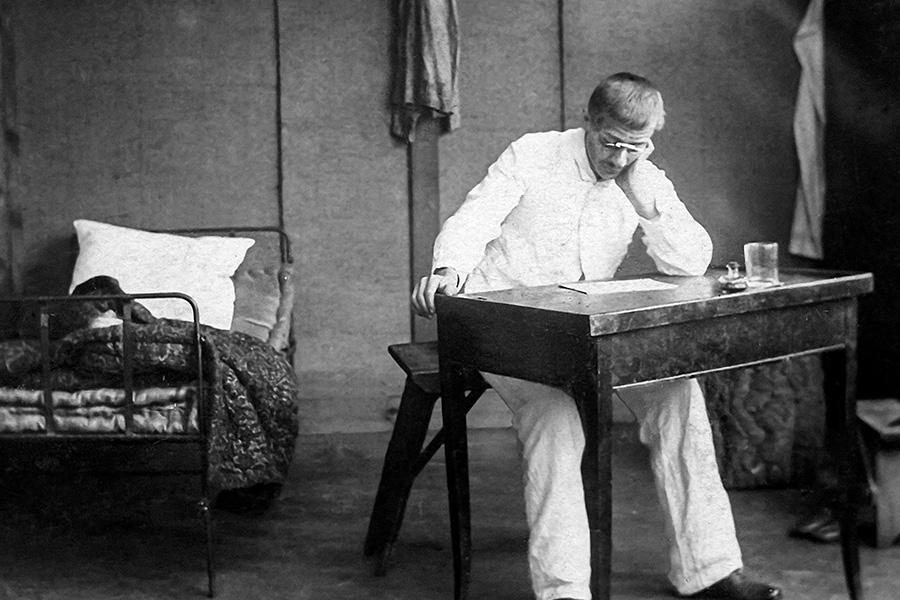

The Unwilling Celebrity

Maurice Samuels’s Alfred Dreyfus is a biography of the very private man at the center of one of the greatest public controversies of modern times.

Alfred Dreyfus: The Man at the Center of the Affair

by Maurice Samuels

April 18, 2024 issue