Last Christmas, I gave my mother a copy of The Pursuit of Happiness by Maira Kalman. Like many other adult Maira Kalmanites, I had discovered the book when it ran as an illustrated blog on The New York Times web site. My mother and I have similar taste in books so I thought she would love it. But a few days later, she called me, quite agitated, irate even, saying “What is this bizarre book you gave me? The letters go all over the page. It’s like a children’s book. What on earth gave you the idea I would want to read this?” An hour later, she called back. “Just forget what I said. I just had to get used to it. What a wonderful book!”

It’s true that my mother is a bit volatile. It’s also true that Maira Kalman writes children’s books—Sayonara Mrs. Kackleman and the Max series, about the adventures of a canine cosmopolite, among them—a fact that will always, I guess, keep some critics, and some mothers on first glance, from taking her seriously. But a more important piece of information about The Pursuit of Happiness is not its picture book bloodlines, but its earlier existence on the web, a place where it looked even more glorious and spoke to its readers even more intimately than it did when published as a book.

Kalman’s illustrated blogs exist online as a kind of video-game for adults: bright, engaging narratives winding their ways forward, backward, sideways, then on to the next exciting level. The Pursuit of Happiness, for example, examined opera, Wittgenstein’s sister’s radiator, Helen Levitt’s bathtub, fabulous hats, and George Washington’s teeth. Kalman writes about the cemetery where her husband is buried and paints a picture of a dog lying between his grave and the grave of George Gershwin. She goes to President Obama’s inauguration and marvels at a museum guard’s perfect red eyebrows. She is an ironist who does not protect herself with irony.

Because the bright paintings and the meandering narrative work so well in her blogs, shaped and lit with a computer’s distinctive light and parameters, it was with great curiosity that I went to see “Maira Kalman: Various Illuminations (of a Crazy World)” at The Jewish Museum, to see her original paintings and drawings, and to see if I would prefer the screen versions even to the originals.

The answer is, No!

No screen could take in the variety of Kalman’s generous and idiosyncratic imagination. And that, it turns out, is what was on exhibit at The Jewish Museum.

Exiting the elevator, one comes face to face with a wall covered with Maharam wall paper on which small Kalman images cavort—odd birds with long legs, ladies in hats, men skating without skates. The design is called On This Day, and what first seems like a random scattering of sketches becomes, on inspection, a strangely realistic depiction of what the world, the urban world anyway, so often is: odd individuals engaged in parallel play. Immediately recognizable as Kalman’s turf, it also feels like home.

I then turned right instead of left, accidentally entering the last room, “Many Tables of Many Things,” first. I know artists and curators work hard at what goes where, but I’m glad I encountered this room at the very beginning, without any preparation. Here was displayed a motley gathering of objects: spools of twine, shiny shoes, a list of the names in Part I of The Idiot, a shoe box with tiny files holding bits of the mosses of Long Island , a primer for colloquial Persian: an accidental assortment of things, stuff that could have been from an abandoned closet in an abandoned house in an abandoned town, but was not, of course, accidental at all. It was saved and chosen and placed in that room for me to see. There was a sublime list of colors that appear in Madame Bovary, which began:

green cloth

black buttons

red wrists…

The lists, the boxes, the fez—it was beautiful, a glimpse of a spontaneous, intensely personal taste, a collection of artifacts, a tender moment of exposed sensibility. A note from Proust in huge Kalman letters scrawled on the wall becomes a poem of great comic profundity:

My Dear Madame,

I just noticed that I

forgot my cane at your

house yesterday. Please

be good enough to give it

to the bearer of this letter.

P.S. Kindly pardon me for

disturbing you, I just found my cane.

Marcel Proust

to Princesse Clermont-Tonnerre

The room, with its ladders and its dessicated onion rings displayed in a glass case, was really less a museum exhibit than an act of sharing. Thank you, Maira Kalman, for letting me in to your very own life of the mind. That’s what I thought. And if I’m picking up Maira Kalmanisms, Good for me! (Kalman’s voice on the page, or the screen, or the many other surfaces she writes on, is both direct and confiding. Perhaps this is the influence of all those wonderful children’s books. Whatever it comes from, she writes as if we were good friends, and I choose to believe her).

Advertisement

The less predictable the objects in the big room, the more intimate the experience became. And the more the creator’s hand could be discerned. Like the 19th-century clergyman naturalist seeing the hand of god in a butterfly’s markings or the pattern of a fern’s fronds, the hand of Maira Kalman appeared everywhere, in a pile of old suitcases, in a rusty funnel. She sees, she marvels, she rejoices—Look what I’ve found! I can hardly believe it exists! But it does!—that is the message in this room, in this exhibit, in all her work, really. God may be dead, but there are still plump red tassels holding back the curtains in the Library of Congress.

Then came the paintings, not all that much bigger than they appear on a computer screen, many of which I recognized as old friends. My favorite is of the young Nabokov in white shorts holding an open book about butterflies, an expression of dreamy intelligence on his face. Some pictures were stark, like Dead Man, a figure in black lying on the snow. Others, like Sunny Day at the Park, were populated and strange, a giant ballerina standing next to a small one. In Herring and Philosophy Club, it is the plates of fruit and brown bread that populate the picture.

And there is, of course, New Yorkistan, the New Yorker cover that made everyone smile at a time when everyone needed to smile.

In one room, a swath of heavy silk woven with Kalman designs is draped over an ironing board, beside it a Vans slip-on sneaker made of the same fabric. On a small handwritten tag, Kalman’s distinctive wavy letters, out of the context of her art, look both forlorn and authoritative, and they anoint the lordly silk drapery and the funny, fancy sneaker with both the majesty of a museum treasure and the spinstery admonishment of a persnickety old auntie: “Please do not touch the textiles,” says the tag.

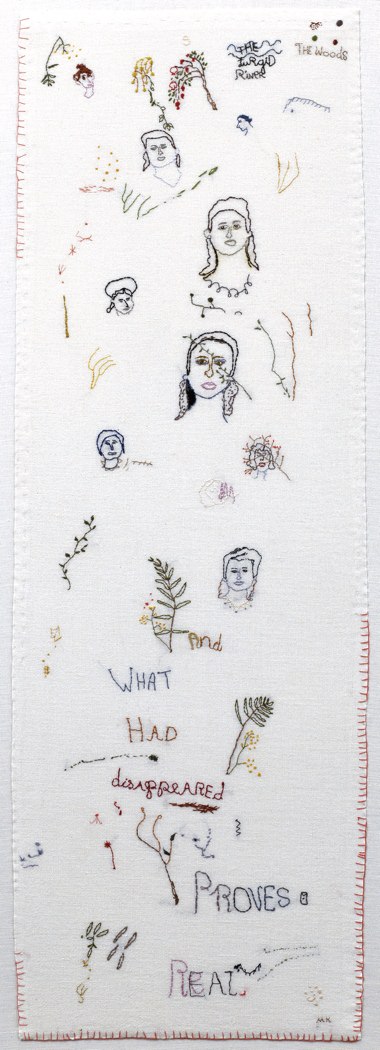

There is embroidery on linen, too, which looks like it might have been picked up a thrift shop, except the embroidery does not spell out “Home Sweet Home.” In one deeply moving work of four panels called Goethe: An Embroidery in 4 Parts, Kalman stitches a passage from Faust interspersed with stitched portraits of her mother. She did this after her mother died. The last panel ends with the lines: “What had disappeared proves real.”

Perhaps Kalman’s greatest gift is that her work embodies both the ironic and the earnest at their best, at the place where they come together and create lyrical, personal truth. She is such a magnanimous artist. She invites us, welcomes us, into the most intimate, unprotected place of all: daydreams.

Who can resist her? Certainly not me. Or, it turns out, my mother.

“Maira Kalman: Various Illuminations (of a Crazy World)” is on view at The Jewish Museum through July 31.