It may seem frivolous to speak of a favorite book in the Bible but mine is Jonah, by far. A sly masterpiece of four brief chapters, Jonah reverberates in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, where it is the text for Father Mapple’s grand sermon. Tucked away in the Book of the Twelve, with such fierce prophets as Amos and Micah, Jonah is out of place. It should be with the Writings—Song of Songs, Job, Koheleth—because it too is a literary sublimity, almost the archetypal parable masking as short story. The irony of the J Writer* is renewed by the author of Jonah, who may well be composing a parody of the prophet Joel’s solemnities. Joel’s vision is of nature’s devastation: “the day of the locust.” Jonah’s counter-vision is of survival, dependent upon divine caprice.

I first was charmed by Jonah as a little boy in synagogue on the afternoon of the Day of Atonement, when it is read aloud in full. It seemed to me so much at variance, in tone and implication, from the rest of the service as to be almost Kafkan in effect.

The author of Jonah probably composed it very late in prophetic tradition, sometime during the third century B.C.E. There is a prophetic Jonah in 2 Kings 14:25 who has nothing in common with the feckless Jonah sent to announce to the people of Nineveh that God intends to destroy their city to punish them for their wickedness. The earlier Jonah is a war prophet, while our Jonah sensibly runs away from his mission, boarding a ship sailing for Tarshish.

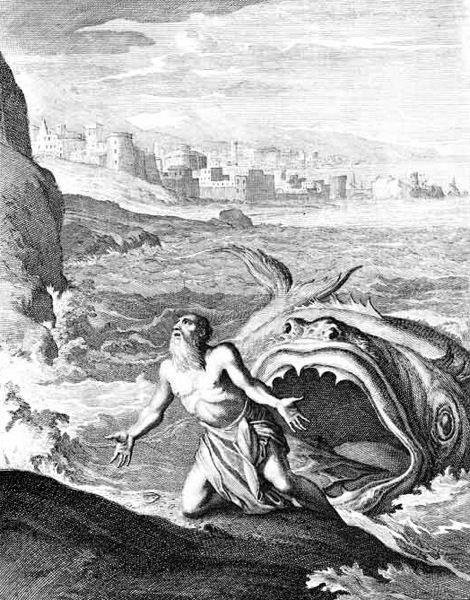

Nobody comes out looking very impressive from the book of Jonah, whether God, Jonah, the ship captain and his men, or the king of Nineveh and his people. Even the gourd sheltering Jonah from the sun comes to a bad end. There is of course the giant fish (not, alas, a whale) who swallows up Jonah for three days but then disgorges him at God’s command. No Moby Dick, he inspires neither fear nor awe.

William Tyndale translated Jonah, providing the King James Bible with its base text but not the humor that shines through its revisions. In a rather negative Prologue to his version (a powerful piece of narrative) Tyndale nastily compared the Jews who rejected Jesus to the people of Nineveh who believed Jonah and repented. The comparison is lame but reminds me that Tyndale, a great writer, also was a bigot.

Jonah’s book is magnificent literature because it is so funny. Irony, even in Jonathan Swift, could not be more brilliant. Jonah himself is a sulking, unwilling prophet, cowardly and petulant. There is no reason why an authentic prophet should be likable: Elijah and Elisha are savage, Jeremiah is a bipolar depressive, Ezekiel a madman. Paranoia and prophecy seem to go together, and the author of Jonah satirizes both his protagonist and Yahweh in a return to the large irony of the J Writer, whose voice is aristocratic, skeptical, humorous, deflationary of masculine pretense, believing nothing and rejecting nothing, and particularly aware of the reality of personalities.

The prophet Jonah, awash with the examples and texts of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Joel, rightly resents his absurd status as a latecomer sufferer of the anxiety of prophetic influence. Either Nineveh will ignore him and be destroyed, making his mission needless, or, if it takes him to heart, he will prove to be a false prophet. Either way his sufferings are useless, nor does Yahweh show the slightest regard for him. Praying from the fish’s belly, he satirizes the situation of all psalmists whosoever.

As for poor Nineveh, where even the beasts are bedecked in sackcloth and ashes, Yahweh merely postpones its destruction. That leaves the Cainlike gourd, whose life is so brief and whose destruction prompts poor Jonah’s death-drive. What remains is Yahweh’s playfully rhetorical question:

And should not I spare Nineveh, that great city, wherein are more than sixscore thousand persons that cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand; and also much cattle?

Presumably the cattle (“beasts” in the Hebrew) are able to tell one direction from another, unlike the citizens of Nineveh, Jerusalem, or New York City. Tucking Jonah away as another minor prophet was a literary error by the makers of the canon. Or perhaps they judged the little book aptly, and were anxious to conceal this Swiftian coda to prophets and prophecy.

* According to one theory of Biblical criticism, the Five Books of Moses are derived from the writings of several different authors: the Yahwist or J Writer is a southern writer who may well have composed at the court of David and Solomon.

This piece is drawn from Harold Bloom’s The Shadow of a Great Rock: A Literary Appreciation of the King James Bible, which will be published in September.

Advertisement