This is the third in a series of excerpts from Robert Walser’s Berlin Stories, which have been translated into English for the first time by Susan Bernofsky, and just published in a [new edition by New York Review Classics]((http://www.nybooks.com/books/imprints/classics/berlin-stories/). The other pieces in the series can be found here and here. —The Editors

A lager please! The tap man’s known me for ages. I gaze at the filled glass a moment, take it by the handle with two fingers, and casually carry it to one of the round tables supplied with forks, knives, rolls, vinegar, and oil. I place the sweating glass in an orderly fashion upon the felt coaster and consider whether or not to fetch myself something to eat. This food-thought propels me to the blue-and-white-striped cold-cuts damsel. I have this lady serve me a plate of assorted open-face sandwiches and, thus enriched, trot rather indolently back to my seat. Neither fork nor knife do I use, just the mustard spoon, with which I paint my sandwiches brown before inserting them so cozily into my mouth that it is perhaps tranquility itself to witness this.

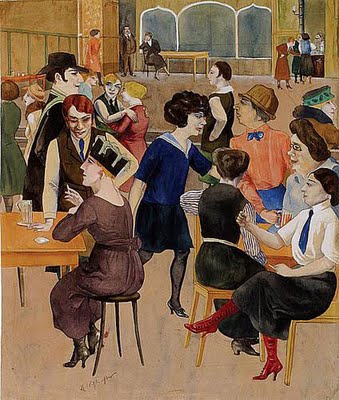

Another lager please! At Aschinger, you quickly adopt a familiar food-and-drink tone of voice; after a certain amount of time there, a person can’t help talking just like Wassmann at the Deutsches Theater. Once you have your fist around your second or third glass of beer, you’re generally driven to engage in all manner of observations. It is imperative to note with precision how the Berliners eat. They stand up as they do so, but take their own sweet time about it. It’s a myth that in Berlin people only bustle, whizz, and trot about. People here have a nearly comical understanding of how to let time flow by; after all, they’re only human. It’s a sincere pleasure to watch people fishing for sausage-laden rolls and Italian salads. The payment is extracted mostly from vest pockets, almost always just a matter of small change.

Now I’ve rolled myself a cigarette, which I light at the gas flame beneath its green glass shield. How well I know it, this glass, and the brass chain to pull on. Famished and satiated individuals are constantly swarming in and out. The dissatisfied quickly find satisfaction at the beer spring and the warm sausage tower, and the satiated dash out again into the mercantile air, each generally with a briefcase beneath his arm, a letter in his pocket, an assignment in his brain, firm plans in his skull, and in his open palm a watch that says the time has come. In the round tower at the center of the room reigns a young queen, the sovereign of the sausages and potato salad—she’s a bit bored up there in her quiver-like surrounds. An elegant lady enters and with two fingers skewers a roll spread with caviar; at once I bring myself to her notice, but in such a way as if being noticed were of no concern to me at all.

Meanwhile I’ve found time to lay hands on another beer. The elegant lady is somewhat hesitant to bite into the caviar marvel; of course I immediately assume it to be on my account and none other that she is no longer fully in control of her masticatory senses. Delusions are so easy and so agreeable. Outside on the square is a racket no one really hears: a tumult of carriages, people, automobiles, newspaper hawkers, electric trams, handcarts, and bicycles that no one ever really sees either. It’s almost unseemly to think of wanting to hear and see all these things, you’re not new in town. The elegantly curved bodice that was just nibbling bread now quits the Aschinger. How much longer am I planning on sitting here anyhow? The tap boys are enjoying a calm moment, but not for long, for here they come rolling in again from out-of-doors to throw themselves thirstily upon the bubbling spring.

Eaters observe others who are similarly working their jaws. While one person’s mouth is full, his eyes can simultaneously behold a neighbor occupied with popping it in. And they don’t even laugh; even I don’t. Since arriving in Berlin, I’ve lost the habit of finding humanity laughable. At this point, by the way, I myself request another edible wonder: a plank of bread bearing a sleeping sardine upon a bedsheet of butter, so enchanting a vision that I toss the whole spectacle down my open revolving stage of a gullet. Is such a thing laughable? By no means. Well, then. What isn’t laughable in me cannot be any more so in others, since it’s our duty to esteem others more highly than ourselves no matter what, a worldview splendidly in keeping with the earnestness with which I now contemplate the abrupt demise of my sardine pallet.

Advertisement

A few of the people near me are conversing as they eat. The earnestness with which they do so is appealing. As long as you’re undertaking to do something, you might as well set about it matter-of-factly and with dignity. Dignity and self-confidence have a comforting effect, at least on me they do, and this is why I so like standing around in one of our local Aschingers where people drink, eat, talk, and think all at the same time. How many business ventures were dreamed up here? And best of all: You can remain standing here for hours on end, no one minds, and not one of all the people coming and going will give it a second thought. Anyone who takes pleasure in modesty will get on well here, he can live, no one’s stopping him. Anyone who does not insist on particularly heartfelt shows of warmth can still have a heart here, he is allowed that much.

1907

—translated by Susan Bernofsky