There are certain composers whose music we can recognize and identify immediately. It is unnecessary to listen to more than a few moments of any mature work by Olivier Messiaen, Elliott Carter, or Philip Glass (to name three dissimilar artists) to realize who was responsible for its creation. But there are others whose music may change radically from piece to piece—or, for that matter, from measure to measure. The German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007) falls into this camp.

Stockhausen burst on the scene directly after World War II, a stateless, brilliant representative of the “new” Germany whose mother had been euthanized for what the Nazis considered mental illness and whose father, a soldier, had disappeared during the war. By the mid-1950s, through his ambition and ceaseless creativity, he was ranked with Pierre Boulez and John Cage as a controversial avatar of all that was new, strange, and challenging in classical music. He composed in an astonishingly wide range of styles: electronic music, serial music, aleatory (or chance) music, in which some parts of the composition are determined by performers. His works were scored for everything from the tape recorder to solo piano, music boxes, multiple orchestras, and full opera companies.

But for the past thirty years, most of Stockhausen’s music has been all but impossible to hear, and a generation or more has come of age without the slightest understanding of what he once meant to young composers and musicians, who cheered him on as passionately as an older generation rejected him. From the 1950s through the early 1980s, almost all of Stockhausen’s compositions were issued on LP by the Deutsche Grammophon label, which disseminated his work throughout the world. When the leading recording format changed to CD, around 1982, Stockhausen took back all of his rights and the majority of his significant works became available through him, at outrageously expensive prices (while the composer was still living, some of the discs cost more than $100; the prices have recently been lowered).

Few young people, therefore, had the means to learn about Stockhausen for themselves anymore, unless they found one of his used Deutsche Grammophon LPs by chance, or heard a performance of one of his very few works that were easily accessible in printed score (a number of his recordings have found their way to Youtube, though they quickly disappear). Certainly these newcomers would have been surprised to know that Stockhausen was once so influential—and, for that matter, very famous. There may be no more telling sign of the popular stature he once held than a quick glimpse at the familiar faces the Beatles chose for the cover of their ambitiously all-embracing Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, where, in the top row, you will find Stockhausen nestled between Lenny Bruce and W.C. Fields and only a few people removed from Mae West, Carl Jung, and Bob Dylan.

Stockhausen’s work abounds in contradictions. He composed music of Webernian concentration (the Klavierstuck No. 3, a flash of brittle, pianistic lightning that lasts less than thirty seconds) and a massive series of experimental operas that make Wagner’s Ring cycle seem laconic. (The Licht series, created between 1977 and 2003, includes seven operas, one for every day of the week, that add up to a total of twenty-nine hours of music). He wrote fiercely organized, precisely notated serial compositions alongside conceptual works that leave virtually every traditional musical choice (pitch, rhythm, timbre, and duration) up to the performer. He was a pioneer in the development of profoundly complicated music for several orchestras and choruses, yet one of his great masterpieces (Stimmung) is a lyrical, hypnotic, and near-motionless seventy-five-minute work for six a cappella solo voices, sometimes sung cross-legged on the floor in a darkened room.

Stockhausen won his first fame in 1955 with what is widely considered the first great electronic composition, Gesang der Jünglinge (Song of the Youths), which combined the recorded voices of children with purely synthesized sounds to create a sort of contemporary Mass (whenever the text can be deciphered, the words praise God). This thirteen-minute tape piece was originally intended for an audience surrounded by loudspeakers in every corner of the hall. Gesang der Junglinge was later released on LP, where it necessarily lost its three-dimensional spatial qualities, but proved a work of singular poetry and ethereal beauty that has diminished not at all.

After this electronic beginning, Stockhausen continued to explore spatial music with live instruments. Gruppen (1957) was written for three orchestras, arranged to surround the audience on three sides. Carre (1960) was scored for four orchestras and four choruses, fashioned in what Stockhausen called “moment” form.

“In the concept of the ‘moment,’ Stockhausen sought a resolution of listeners’ difficulties in experiencing form in serial music,” G.W. Hopkins observed in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. “Each individually characterized passage in a work is regarded as an experiential unit, a ‘moment,’ which can potentially engage the listener’s full attention and can do so in exactly the same measure as its neighbors. No single ‘moment’ claims priority, even as a beginning or ending; hence the nature of such a work is essentially ‘unending’ (and indeed ‘unbeginning’).” Stockhausen himself put it somewhat more plainly. “You can confidently stop listening for a moment,” he said, “if you cannot or do not want to go on listening, for each moment stands on its own.”

Advertisement

The Klavierstucke IX, first performed in 1963, begins with a brutally dissonant chord repeated 156 times—not, as it may seem, a precursor of minimalism but rather a protracted, calibrated fade-out—before moving into a Olivier Messiaen-like aviary of trills and twitters. Klavierstucke X is as brilliantly virtuosic as any nineteenth-century operatic paraphrase by Franz Liszt, filled with scurrying grace notes, hammered tone clusters, and a sense of heart-in-mouth drama. I remember the way a good portion of an Avery Fisher Hall audience (virtually all those who hadn’t left when the nineteenth-century part of the program was over) rushed the stage when Maurizio Pollini played Klavierstucke X at the end of one of his programs in 1983. It was one of the most exciting things I ever saw in recital and I wonder why more pianists don’t take these works up as encore pieces.

Because Stockhausen’s piano music was published (by Universal Edition), it has been recorded and performed with some regularity. The score for Stimmung is also available. The same cannot be said for the massive electronic epic Hymnen (1968) which combined more than forty national anthems into a two-hour exploration of vast panoplies of sound. A third major work from 1968, Aus den sieben Tagen (From the Seven Days), was entirely conceptual. The “score” for one movement began with the following instruction:

play a sound

play it for so long

until you feel

that you should stop

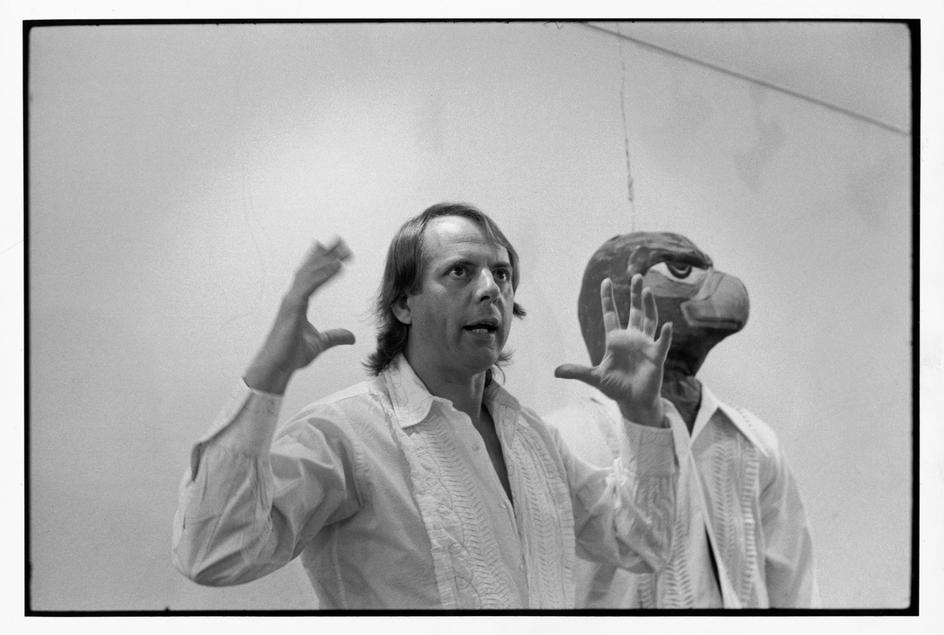

One hopes that recordings of this music, made available at prices that average listeners can afford, might inspire a reevaluation of Stockhausen’s important work. Only then will we be able to take the full measure, once again, of this Promethean shaman, theorist and composer.