Some old views of cities—the citrus grove in Los Angeles, the horse-drawn cart in a muddy lane in downtown Buenos Aires—are intriguing because the places they show are so unrecognizable. But old images of Rio de Janeiro are intriguing because the place they show is so recognizable. This has something to do with the landscape, and even more with the way it is depicted.

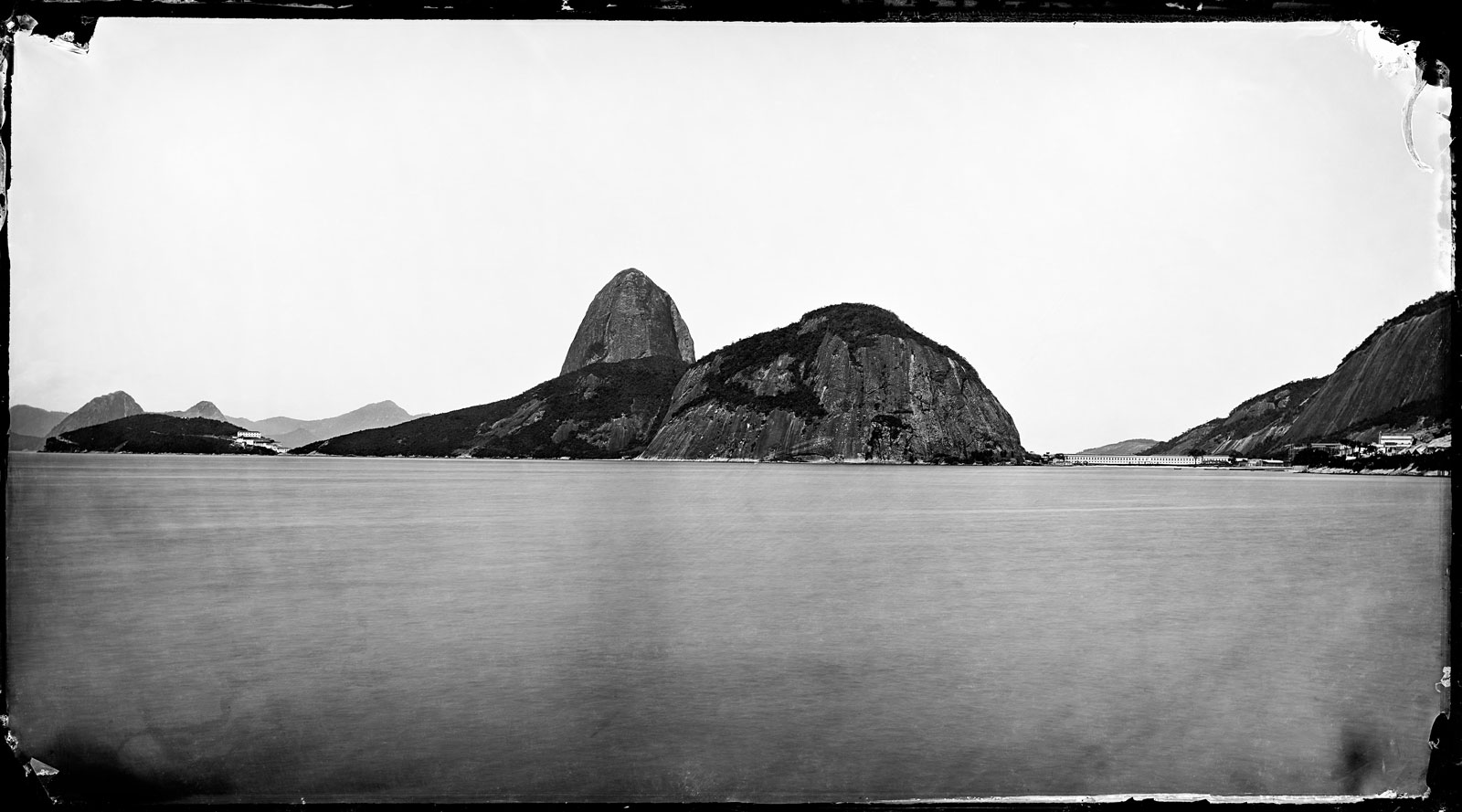

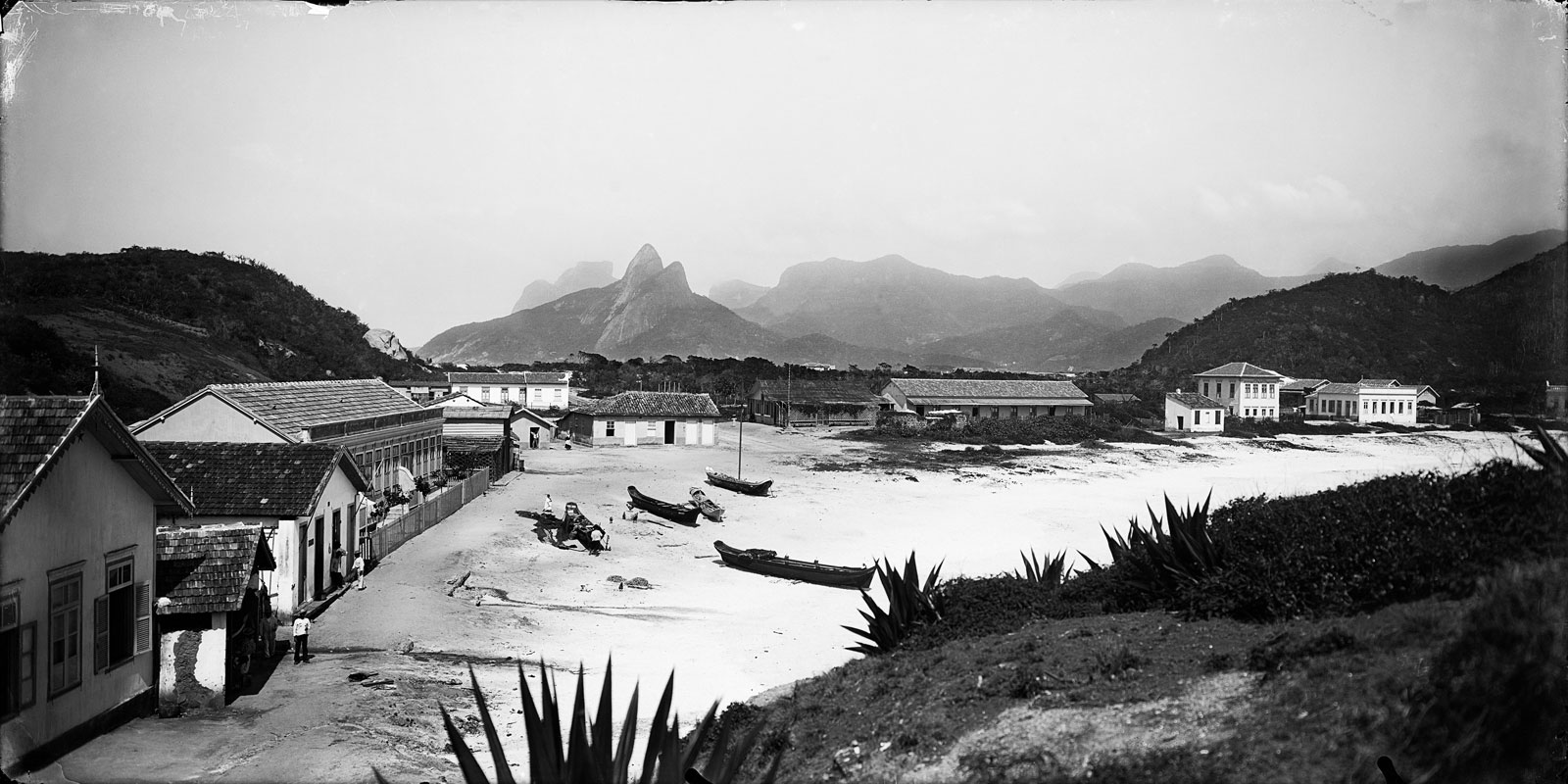

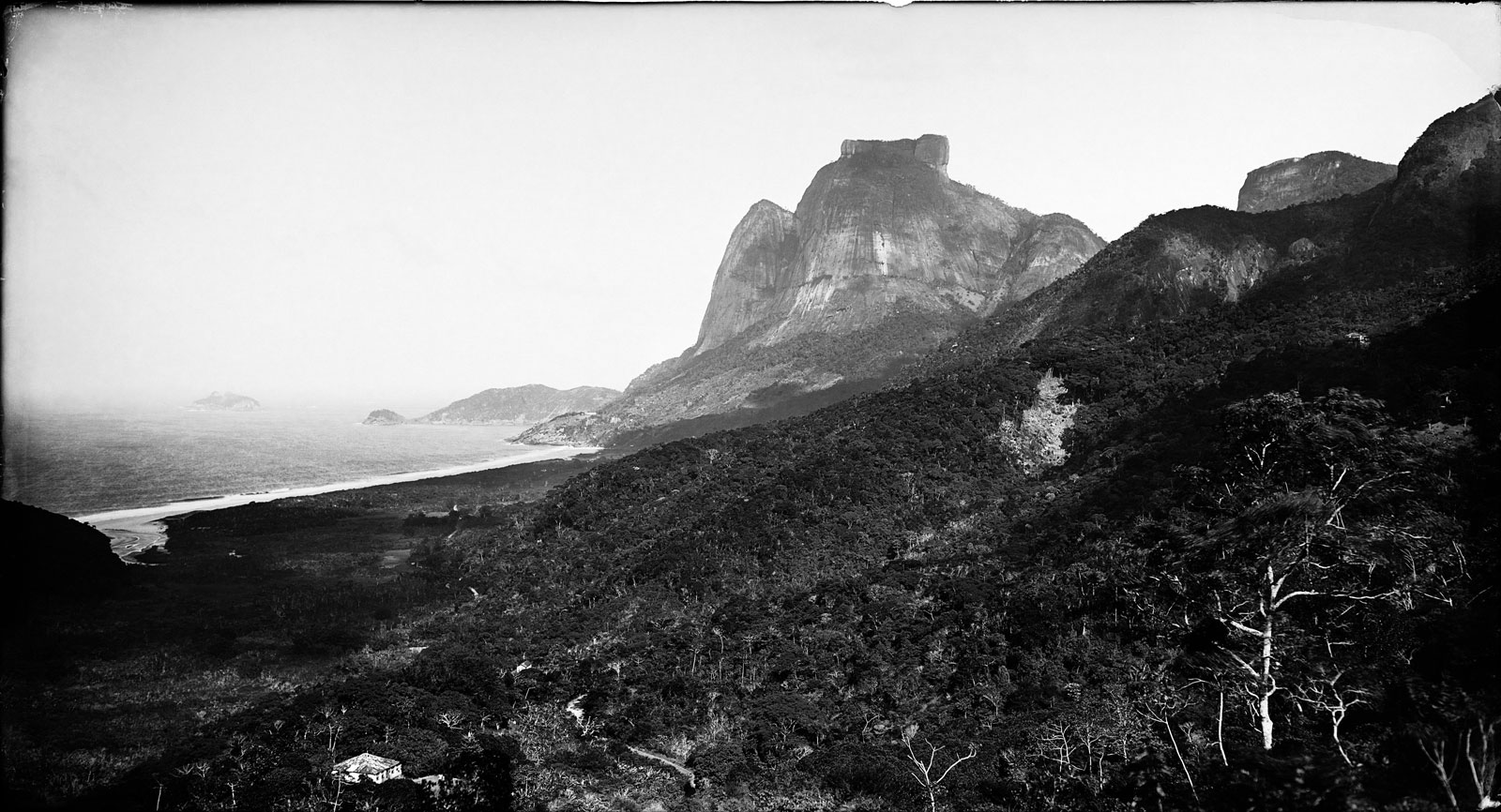

This continuity appears in Rio, a new collection of Marc Ferrez’s photographs of the Rio of the belle époque. With its great forests blanketing its granite-and-crystal mountains, its bright beaches lining its glittering bay, Ferrez’s Rio is a pristine modern capital in a setting that offers a nearly religious vision of paradise. This city is so glorious that it seems calculated to induce belief in the Creator as a benevolent gardener.

To some Olympic tourists—those not frightened off by the reports of raw sewage and mosquito-borne disease—Ferrez’s Rio will seem unspeakably distant from the huge graffitied metropolis of today. But a closer look will reveal that, despite the changes over the last century, some similarities remain, less in the city than in the highly aestheticized view being held up for their admiration.

*

It is a city that seems, then as now, to encourage the photographer, and Ferrez was among the first to take the hint. Over his long career, Ferrez photographed it with every tool of the nascent technology. Born in 1843, a scant four years after Daguerre’s discovery was announced in Paris, he died in 1923, the owner of a chain of cinemas. In life and work, Ferrez ranged widely, but his main subject always remained his native city.

He was the first photographer to lug his heavy equipment up the Corcovado and the Sugarloaf, and to aim his camera down the long ribbons of Copacabana and Ipanema. Still today, nearly a century after his death, we see the city through his eyes. Precisely where he stood, tourists and natives are standing now, grinning into their iPhones. Rio, in large part thanks to Ferrez, is a city of views.

Those views are breathtaking, magnificent. With his leisurely exposures and silky silver tones, Ferrez captured a place that seems like more than a mere city—a place that seems to aspire to metaphor. When, a year before his death, construction began on the gigantic statue of Christ the Redeemer atop the Corcovado, the gesture seemed to reinforce his vision of this city as something supernatural.

It is an artist’s vision, and one that, like Ferrez himself, descends from earlier artists. His father was a sculptor from the Jura named Zéphyrin Ferrez, who arrived in Brazil with the French Artistic Mission of 1816—one of Napoleon’s many inadvertent gifts to the city. When Napoleon invaded Portugal in 1807, the entire Portuguese court, fifteen thousand strong, abandoned Lisbon and took refuge in Rio de Janeiro.

Their arrival was as revolutionary as if, following an invasion of Britain, the King of England had cleaned out Hampton Court and Buckingham Palace and descended, with all his retinue, upon sleepy colonial Boston. The newly christened capital desperately needed an upgrade, and King Dom João VI summoned a boatload of artists and architects from Europe. Most stayed on after Brazil became independent, in 1822, under Dom João’s son.

Strangely enough, then, independent Brazil’s most fervently patriotic art was created by foreigners, in the service of a foreign dynasty. Even by the standards of the age of Romanticism, this art stands out as highly romantic; and even by the standards of a Europe swooning with Rousseauvian fantasies of the tropics, it stands out for its volupté. This was Brazil as paradise, as muse: as tourist destination.

*

When he was seven, Marc Ferrez’s parents suddenly died and he was dispatched to France. He remained there until he was a young man, when he returned to Brazil; throughout his life, his frequent journeys back to France allowed him to keep up with the fast-evolving technology of photography.

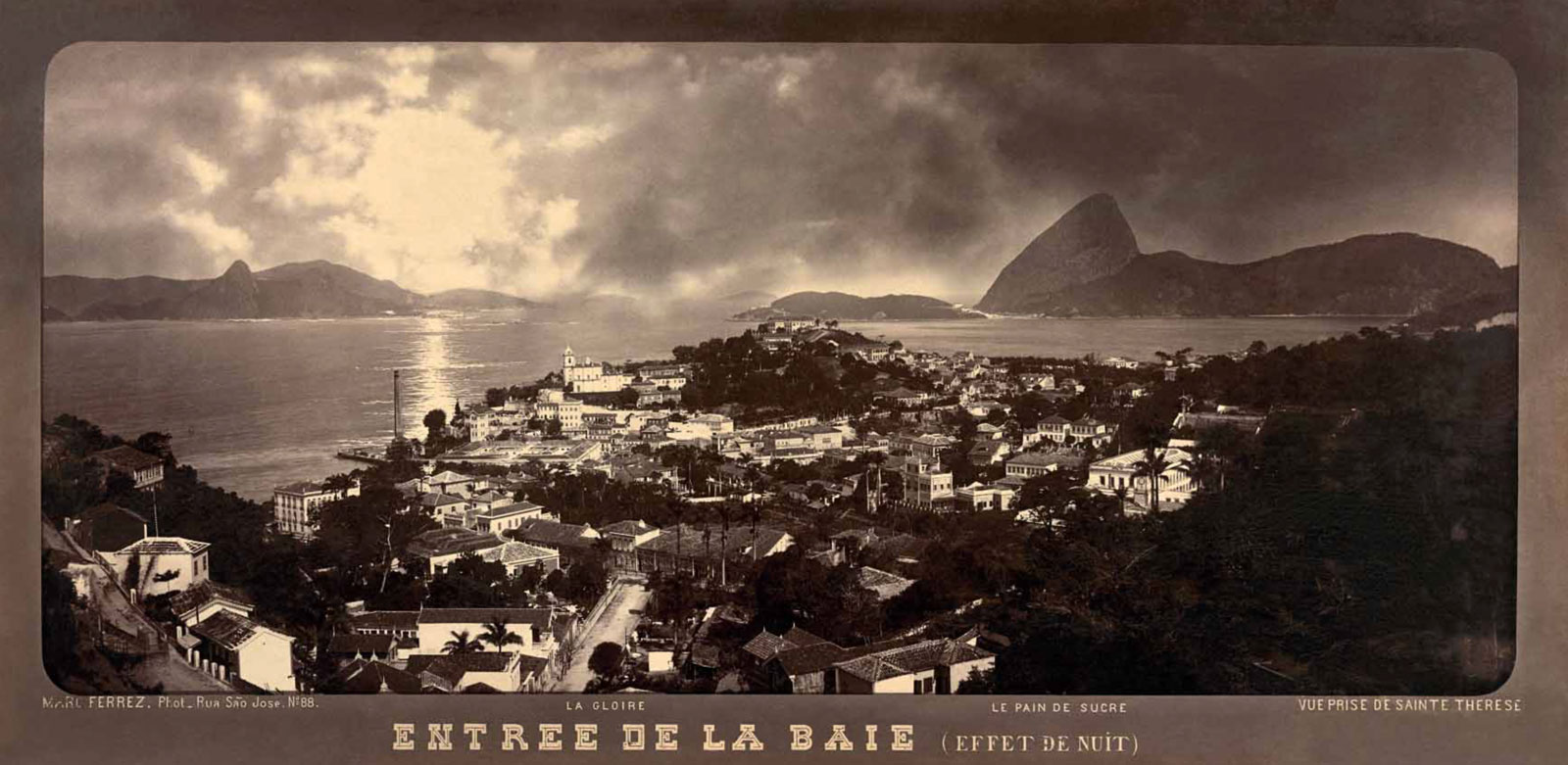

In 1878, he brought to Rio an early panoramic camera he had acquired in Paris. At this point, his work began to approach the earlier—painted—views of the city. Brazil’s stupendous nature seemed designed for the panorama, all the more so in an age when these were mass entertainments. As early as 1827, a huge “view of the city of St. Sebastian, and the Bay of Rio Janeiro” was displayed in Leicester Square.

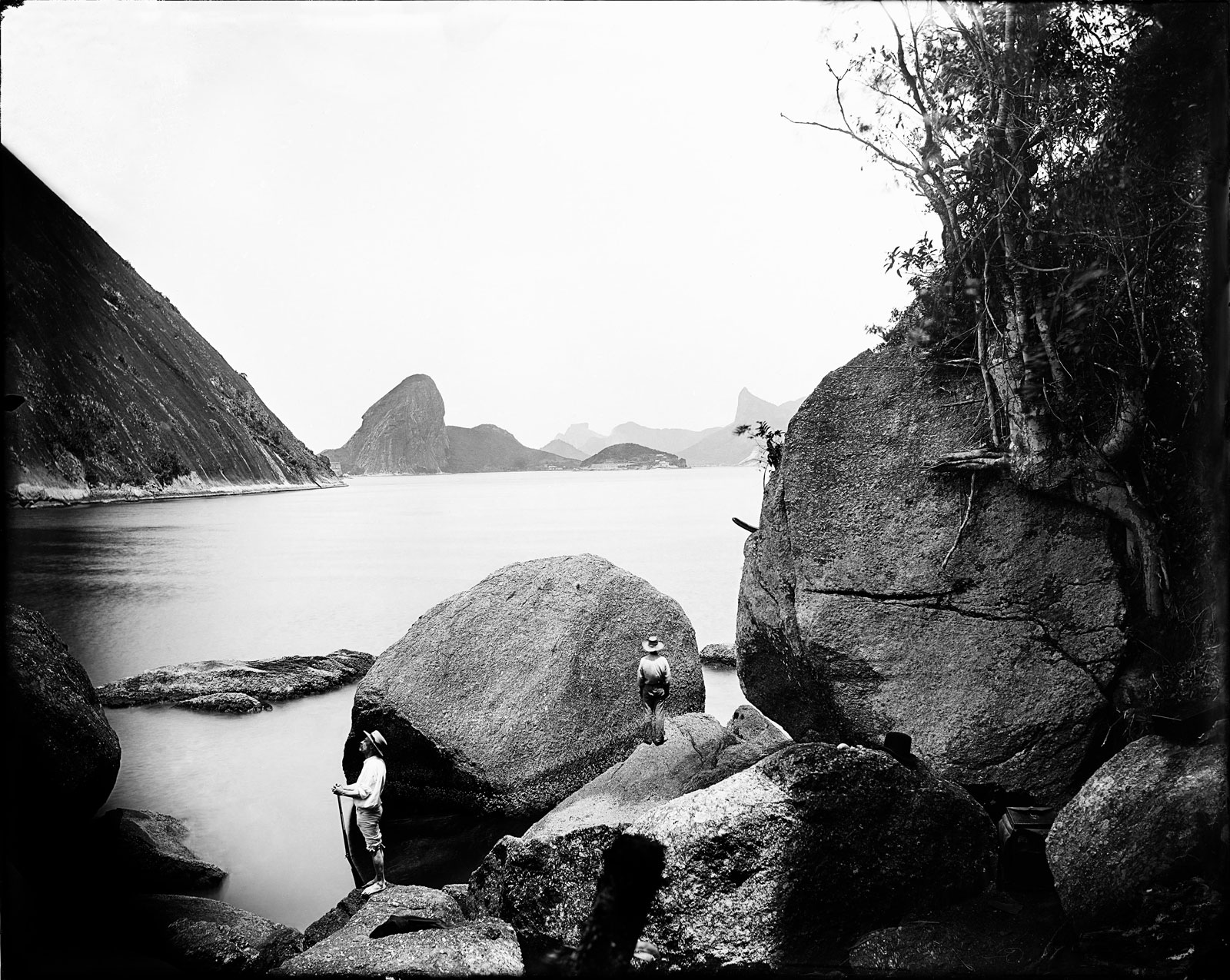

The panorama allowed Ferrez to capture the city as the visitor experiences it today, standing atop peaks, gazing along beaches. These pictures, too, employed a range of painterly conventions: Ferrez frequently used a palm tree as a framing device, for example, a trope of tropical painting that, in Brazil, dates back to the seventeenth-century Dutch painter Frans Post.

Ferrez’s panoramas also included modern novelties, which can be seen from a night view, Entrée de la Baie (Effet de Nuit). From the dazzling moon reflected in the bay to the dark storm clouds gathering over the Sugarloaf, the picture is a summa of black-and-white film, showcasing its possibilities with such a range of dramatic effects that every amateur photographer will wonder how, exactly, it was made.

But if Rio seems made for the camera, that is because, to a large degree, it was. To look through these pictures is to wonder to what degree they are art, and what degree artifice. It was an old question: European painting had always recognized the distinction between land shaped—landscape—and nature brute. A landscape was a human arrangement, and not to be confused with nature.

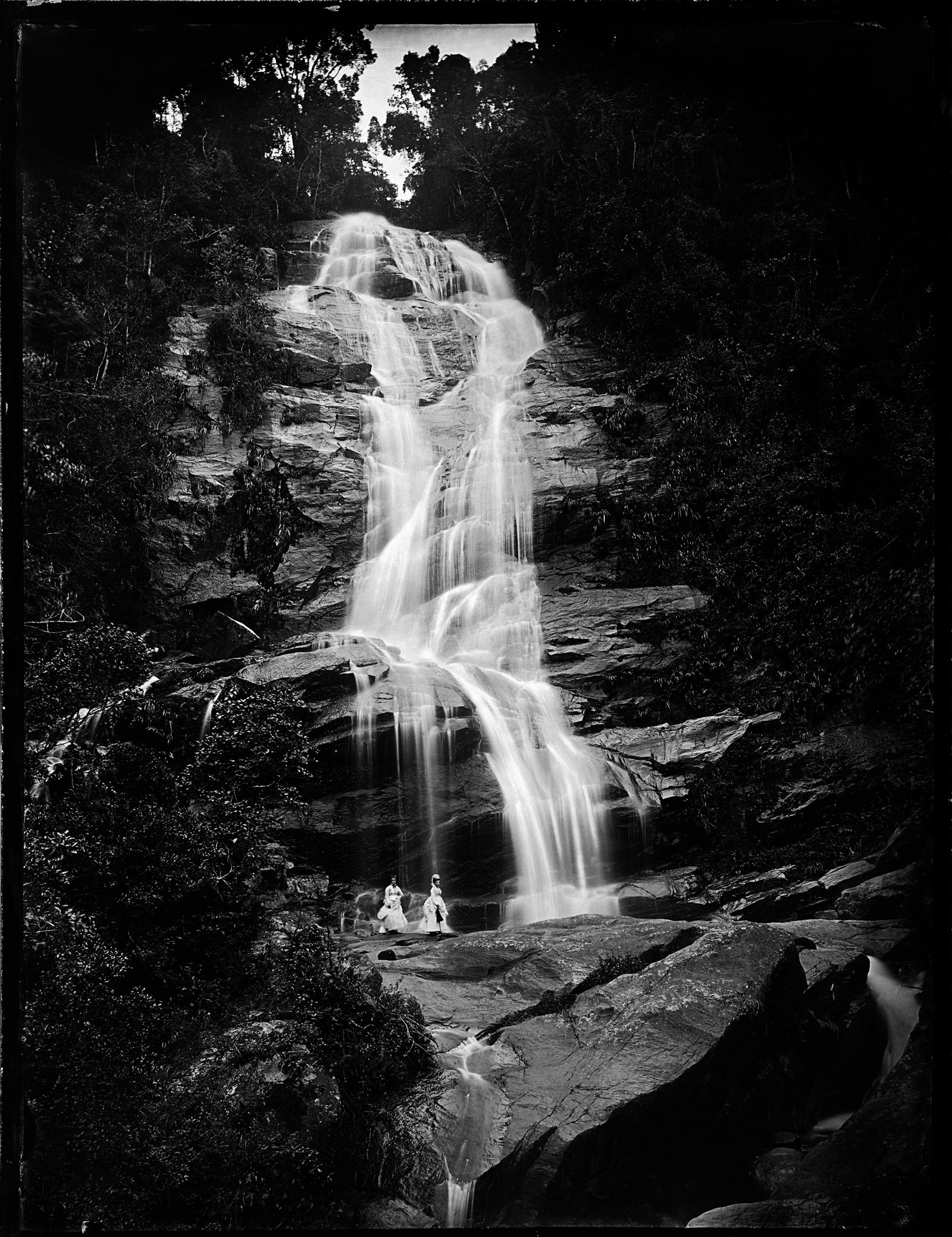

In France, nature brute was decidedly less desirable than a beautifully arranged landscape. But things were more complicated in the New World, whose romantic appeal lay in its untouched, savage state. This state is what Ferrez’s pictures show. Luxuriant with orchids, groaning with palms, the primeval forests on Rio’s great mountains suggest a prelapsarian world, unsullied by the hand of man.

Nothing in these pictures indicates that this Edenic marvel, the Forest of Tijuca, was hardly twenty years old in the 1880s, when most of these pictures were taken. This was the most modern forest in the world: younger, even, than the Bois de Boulogne, constructed between 1852 and 1858—the same year that work began on Central Park.

Work on the Tijuca Forest began four years later, in 1862. It was a herculean task, carried out by imperial decree (and by slaves). It was meant to address an environmental problem that threatened the existence of the city itself: the original forests had been stripped, principally to plant coffee and sugar cane, and this deforestation was drying up the rivers upon which the city’s water supply depended.

There are some hints of human presence in these pictures: a teensy aqueduct, a humble dam, fancily dressed ladies posing at the foot of the waterfalls. But plants grow quickly in Rio de Janeiro. Within a few years, the forest assumed the ancient appearance that makes these pictures Brazilian cousins of the Andean views of Frederic Edwin Church, or the Rocky Mountains of Albert Bierstadt. Here is the New World, in all its virginal splendor: voilà!

*

It is one thing to photograph a forest, of however recent vintage, as a landscape. It is another thing to photograph a city that way. When Ferrez turns to the recognizably man-made, the effect is more disquieting. For all its pomp and beauty, the capital of the Brazilian Empire, one of the world’s largest nations, seems strangely empty.

Part of this is a consequence of the panoramic view. Seen from a promontory, forests and mountains and oceans and spires appear, but people do not register. Still, when looking at this marvelous landscape, the curious viewer wonders about the people who inhabit it. What do they do? What do they look like? Where do they come from? This curiosity will be disappointed, since these people rarely appear.

The ideal city of the Renaissance was often portrayed empty. At most, a handful of well-dressed citizens turned up as props to illustrate the scale of the architecture. They serve the same function in Marc Ferrez’s photographs, in which a few elegant people wander in front of the lens. And even when we see people, we rarely see faces: the odd crowd shot reveals little more than a sea of hats.

Never before—certainly never since—was Rio de Janeiro as spotless as in the photographs of Marc Ferrez. The chaotic, stinky, feverish metropolis described in the Brazilian novels of the nineteenth century has given way to a glittering capital where not a plaza goes unswept, a façade unpainted, or a park unraked, and where wide empty avenues lead gracefully from one “natural” wonder to the next.

In his images, we walk—all by ourselves—up and down a sumptuous avenue, admiring pile after spangled pile. There, on our left, is the Municipal Theater. On the right, across the street, is the Academy of Fine Arts. Banks, then newspapers, then government buildings appear. This is the Avenida Central, and Ferrez show us every detail of the caryatids and spires decorating the boulevard. It was built starting in 1904, under an unelected mayor, Francisco Pereira Passos, who had studied in Paris and dreamed of remaking Rio along Haussmannian lines.

Advertisement

The cost, in Rio as in Paris, was gigantic. For the construction of the Avenida Central, nearly three centuries of architectural heritage were destroyed, and almost four thousand people made homeless. Some were killed. This catastrophe, which led to bloody rebellions and spurred the spread of the slums known as favelas, was justified by an ideology whose central concept was “modernization.”

Mysteriously, this upheaval, in Ferrez’s photographs, registers not at all. When we recall the cost of the reform that made it possible, the missing people along the avenue become unwittingly symbolic. It is here that Ferrez diverges from the Parisian contemporaries to whom he is often compared. One need not wonder what Charles Marville or Eugène Atget would have made of the destruction of such a large swathe of their city, because they photographed it. Ferrez, in contrast, registered the avenue as he registered the forests of Tijuca: as a natural occurrence, happening outside of history.

Of course—except when its architecture was bulldozed and its inhabitants pushed out of the frame—scruffy old Rio never looked like this. But as words like “Entrée de la Baie (Effet de Nuit)” hint, these pictures were not meant for Brazilians. This is not Brazil as it was, or as Brazilians saw it, but Brazil-as-landscape: Brazil as a segment of the Brazilian elite wanted foreigners to see it.

In Ferrez, with his international connections, they found a perfect representative. The country, after all, had a terrible reputation: “For so long Europe has known nothing more of Brazil than the emperor Dom Pedro and yellow fever,” wrote one Brazilian—in French—in 1891. Rio was so known for pestilence that ships heading to Buenos Aires advertised that they did not stop there.

In this setting, Ferrez’s images of cleanliness and modernity, subtitled in French, were highly political—advertorial, even. It is a testament to his genius that they were also so highly successful. In 1923, the year he died, the Copacabana Palace opened on a beach he had shown as uninhabited but for a few fishermen’s shacks. Now, the seedy slave port had its Croisette, its Promenade des Anglais.

*

Exactly two hundred years after the French Artistic Mission arrived in Rio, the city has made itself up to receive its grandest foreign delegation ever. Some of the more than half a million visitors who have come for the 2016 Olympics will doubtless buy this beautiful book of photographs, and gaze at these pictures of a paradise transformed beyond recognition.

They will see, for example, photographs of the rustic idyll on the Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon. Today the lagoon is disgustingly polluted, lined with huge luxury apartment blocks, and strangled by a ring road permanently clotted with traffic. These are the kinds of pictures that, like paintings of lost arcadias, spur one to muse about the nature of modern progress: about how far we have come, and whether it was worth it.

But how unrecognizable is it, really? The city has once again been spruced up for international consumption. The Avenida Central, now the Avenida Rio Branco, has received a makeover. Its terminus, Mauá Square, beside the port where the slave ships docked, has received a futuristic building designed by the starchitect Santiago Calatrava, the frightfully expensive Museum of Tomorrow.

Its location, expense, and pretentious foreign architecture make it an appropriate addition to the avenue. But it is only part of an Olympic city that has redesigned itself as a vast Museum of Yesterday. This tomorrow is, in fact, the yesterday of Pereira Passos, photographed by Ferrez, meant to shove the population out of the picture in order to present a clean modern face to predominantly foreign audiences.

The current mayor, Eduardo Paes, has welcomed comparisons to the bulldozer of a century ago. He has even posed at campaign events beside an actor dressed as Pereira Passos, but this might be selling himself short. More than twenty thousand families have lost their homes in these preparations, earning Paes a gold medal of his own: for having removed more favelas than any previous mayor.

Brazilian politicians of whatever party have long been united by the desire to remove their people, particularly the poor and the black. “Rio de Janeiro went, in about half a century, from being the largest African capital outside Africa to an almost Portuguese metropolis,” writes Angela Alonso in an afterword. “The two regimes converged this way, never satisfied with the people they already had.”

Precisely because Ferrez’s pictures are so beautiful, they deserve something more than coffee-table treatment, and their subject something more thoughtful than a high-end infomercial. If the Potemkin facades along the unpeopled Avenida Central are dreamy to look at, they present the city as Architectural Digest presents a celebrity apartment: the term for this is shelter porn.

Yet there is a crucial lesson here, too. As in the time of the Emperor, the city is threatened by increasingly poisonous waters. Tons of sewage pour, untreated, into the bay and lagoons and beaches where the Olympians are competing. In Ferrez’s era, the city was saved by an audacious environmental project that continues to delight today. If the Forest of Tijuca was an artificial, man-made landscape, that does not make it any less beautiful or useful, and the vision of its architects—of a modern city coexisting peacefully with itself and its environment—is now more urgent than ever.

Marc Ferrez’s Rio is published by Steidl, as part of a two-book set that also includes recent photography of Rio by Robert Polidori.