Most photographers use the camera as a tool of memorialization. They choose which moments to rescue from the enormous trash heap of everyday existence, by referencing some sort of defined visual hierarchy, a scaling of what scenes deserve to be immortalized. A “good” photograph happens when reality lines up in a way that is more valuable than other arrangements (see Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment”), and a good photographer, therefore, is someone with a knack for recognizing that value and clicking the shutter.

That is not how Stephen Shore uses a camera, and his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art makes this apparent. The exhibition casts a wide net, including the anomalous periods when Shore worked abroad, but its main focus is his many photographs of hyper-quotidian America, our stalest shades of red, white, and blue. These quiet and straightforward pictures—of food, buildings, cars, and toilets—show that Shore is best understood as a photographer uninterested in photographing what is agreed to be worthy of capture.

But the true subject of Shore’s work cannot be found in the contents of his photographs alone. When Shore frames a very American breakfast spread at a restaurant in Utah, we may ponder the scene, and what our country’s particular styles of consumption say about us, but to focus entirely on the reality represented would be to miss what makes this extraordinarily ordinary photograph profound. Shore shoots the table from above, from the familiar perspective of someone who has walked away, maybe to go to the bathroom, and returned to find their food served. The silverware is haphazardly placed, the cantaloupe sits askew, the edges of the frame seem to include and exclude details at random. The photograph, a kind of highly intentional accident, is a reminder that when it comes to Shore, it’s not always about what we are seeing, but how we are seeing it.

Shore has had a half-century-long preoccupation with the difference between the way we see the world when we move through it, and the way we see it in images. His hope, he has often said, is to make photographs that look “natural.” For Shore, this means an erasure of mediation, a lightening of his hand in the creation of an image. Writer Lynne Tillman called it Shore’s attempt at “willed objectivity.” Photographer Joel Sternfeld described it as Shore’s “Zen-like, awakened unconsciousness.” Shore simply says he wants his photographs to “feel like seeing.”

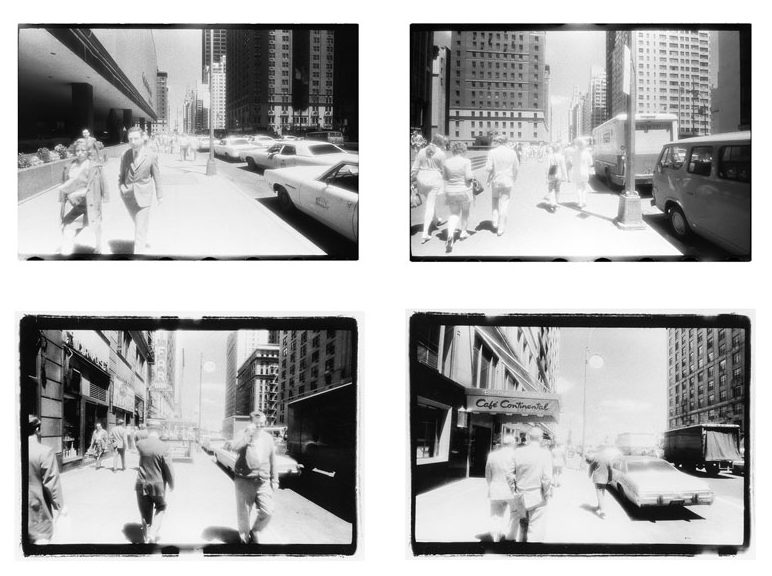

With this in mind, the many phases of Shore’s career, which unfold chronologically in MoMA curator Quentin Bajac’s sprawling layout, begin to look like distinct strategies employed to achieve this effect. At first, he experimented with blunter instruments, making images within tight frameworks reminiscent of those designed by the artist Ed Ruscha. In 1969 Shore made “Circle No. 1,” a series composed of photographs of a friend taken from the perspective of all eight points on a compass. For “Avenue of the Americas” (1970) he took a picture facing north on every corner of New York City’s 6th Avenue between 42nd and 59th streets. These photographs—plain, repetitive and sometimes even poorly exposed—may not be very interesting when examined individually, but that’s not the point. Systems like these allowed Shore to remove himself from the equation, to make an image without entirely dictating its contents.

Unlike Shore’s friend and mentor, Andy Warhol, though, Shore did not want “to be a machine.” He wanted to retain some sense of authorship. He wanted to bring the conceptual spirit of Warholian pop to the documentary tradition of Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and the other great photographic chroniclers of the American condition. So Shore eventually left the systems behind. In 1971 he experimented with a toy camera called the Mick-a-Matic (a Mickey-Mouse-shaped device that is on display at the exhibition) in an attempt to amateurize his work, to remove traces of sophistication. It was around this same time that Shore made his controversial switch from black and white to color. (The renowned modernist photographer Paul Strand famously told Shore that this was a disastrous career move.) Until that point, black and white film served as an aesthetic marker that differentiated the medium from the way we see reality; it elevated a photograph from banality to a work of art. Contemporaries like William Eggleston and Joel Sternfeld were also pioneers of color, but their use of it often added dynamism to their images. Shore, on the other hand, used color to bring photography back down to realism.

Advertisement

That Shore has been so drawn to Instagram recently makes sense, and the photographs he has made while using the app are presented in the exhibition via iPads. Instagram is, after all, definitively diaristic. It might not always be used in that mode these days—when aspirational filters and curation seems to dominate—but the original premise called for unmediated snapshots of everyday life. Shore seems to use the platform in this manner, posting photos of nature, his friends, and pets, creating a large visual repository of sorts. Scrolling through his feed, it’s clear that his artistry is often a strategic stripping away of artfulness. In that respect, Instagram can seem a more natural home for his photographs than the white walls of a prestigious museum.

It’s telling, then, that Shore has expressed mixed feelings about one of his most famous photographs: U.S. 97, South of Klamath Falls, Oregon (1973)—a billboard with a mountain range painted on it in the foreground, a real life mountain range in the background. The picture, clever, beautiful, and a little sad, is a “good” photograph, as close to a “decisive moment” as Shore gets. But it’s when he uses the mundane the way a sculptor might use clay, manipulating a material that seemingly has no inherent character or value, that Shore’s mastery is on full display. The pictures that might have visitors to the museum scratching their heads, thinking, “I could do that,” reveal Shore not just as one of his generation’s great photographers, but as a rare kind of seer—the sort that, with his eyes, can change the way we use ours.

“Stephen Shore” is at the Museum of Modern Art through May 28.