In her first solo show, at Gavin Brown’s enterprise, LaToya Ruby Frazier uses the gallery’s grand, multistory Harlem building to great effect, staging her own grand, multistory portrait of the contemporary United States. The show begins on the ground floor with Frazier’s documentation of the Flint water crisis, and ends on the top floor with blazing scenes from the Californian desert. Along the way, three discrete series of gelatin silver prints, each on its own floor, demonstrate the endemic racism and hazardous decay of post-industrial America, the bond and burden of home for families caught amid these crises, and the redemptive potential of art to tell these stories. Like the camera’s technical process of exposure, Frazier brings things to light that would otherwise remain obscured. “I create visibility through images and storytelling,” she says in the show’s materials, in order “to expose the violation of… human rights.” Her black-and-white photographs are unsentimental witnesses to the furloughed American dream.

We enter into the thick of it on the ground floor with Flint is Family (2016–2017), comprised of images that Frazier made during the five months she spent in Flint, Michigan, with one of its residents, Shea Cobb, and her daughter Zion, in the aftermath of the city’s water crisis. To save money and reward corporate contracts, in 2014 the city switched its water supply from Detroit to the local Flint River, contaminating its residents with toxic levels of E. coli and lead. Officials willfully ignored evidence of tainted water for years. First published in 2016 in Elle magazine alongside a reported story, the photos in Frazier’s Flint series exist somewhere between portraiture and photojournalism. They show the trajectory of a municipal catastrophe through public scenes of protest and private scenes of perseverance.

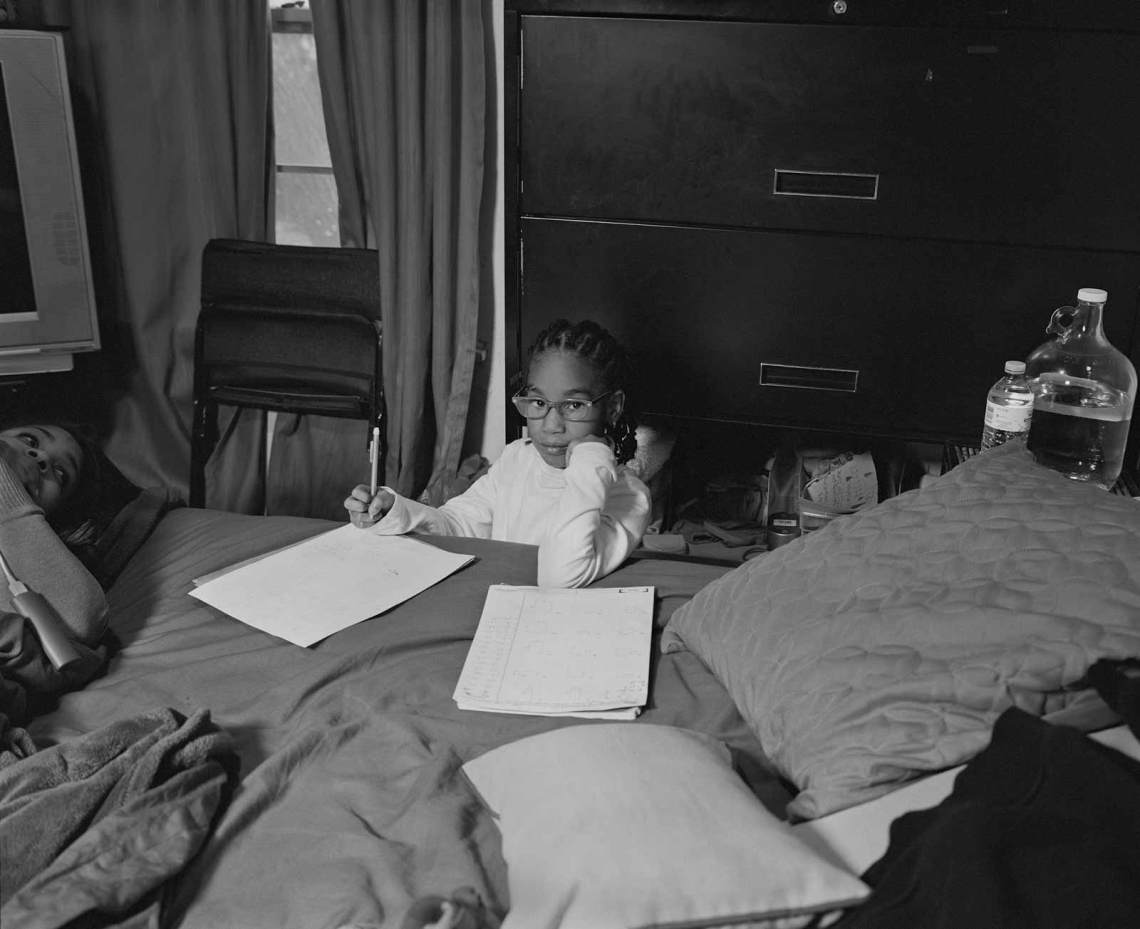

The didactic weight of the project’s backstory, told at Gavin Brown via extended wall labels and with daunting statistics from the American Academy of Pediatrics, is buoyed by Frazier’s images of active daily life: Shea driving a school bus and braiding hair; students who cannot drink from water fountains at school brandishing “Flint Lives Matter” signs and donning hazmat suits at rallies; Shea’s cousins getting married; Zion doing her homework under the watchful eye of her mother; the two out to dinner at their favorite restaurant. “It’s the hustle that gets us through,” Shea explains in an accompanying video, also titled Flint is Family. There are no images of passive desperation.

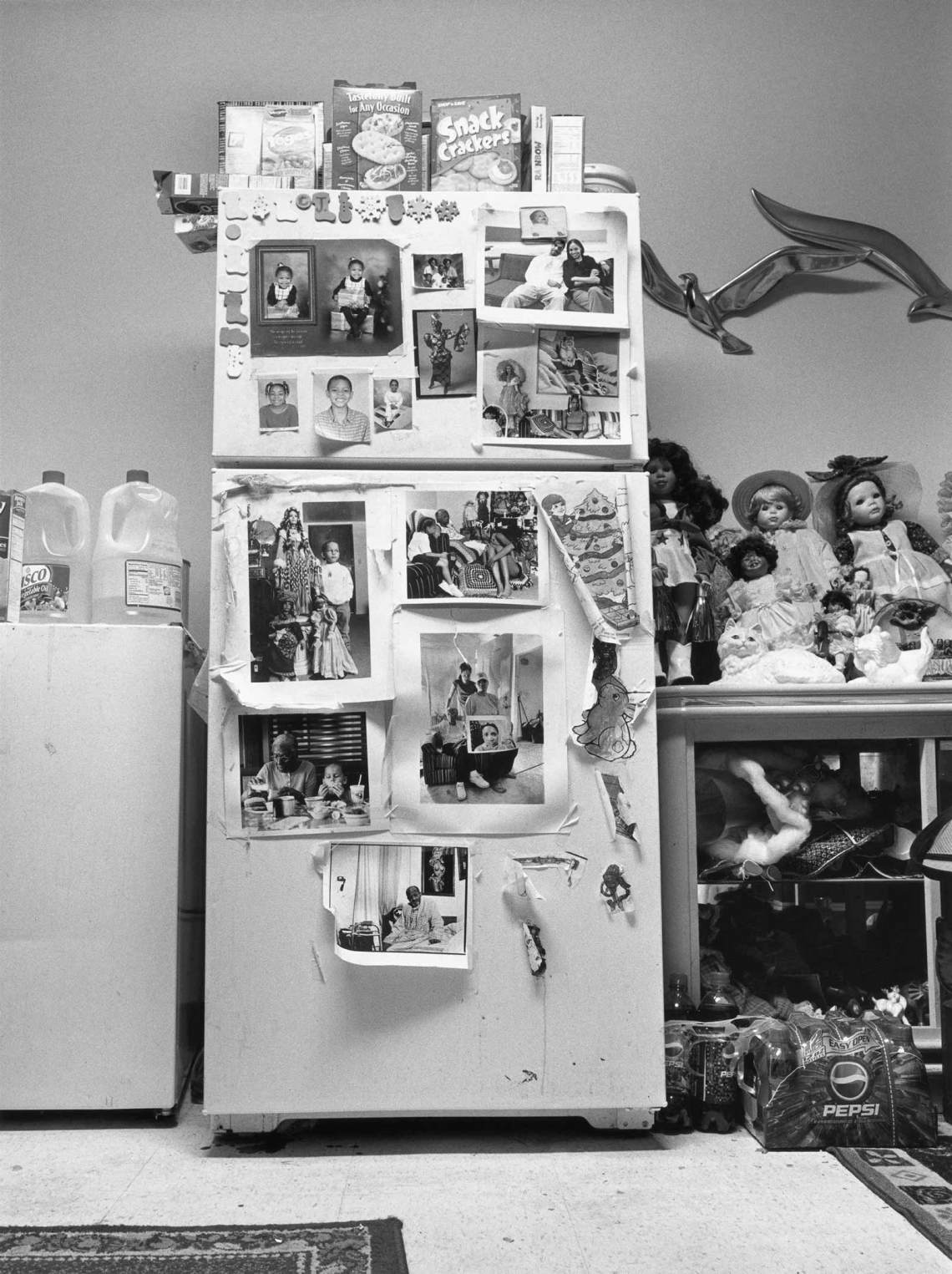

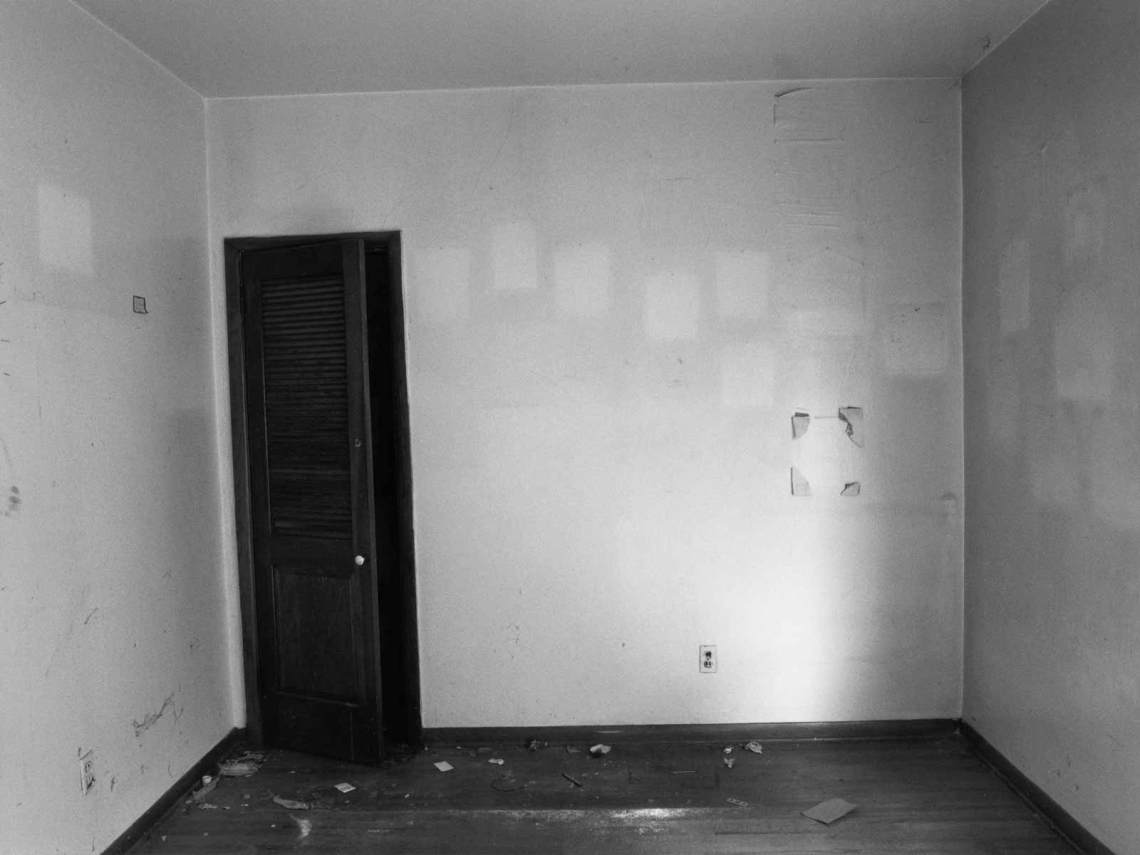

The second floor contains selections from The Notion of Family (2001–2014), Frazier’s project documenting her own family in the once-thriving steel-mill town of Braddock, Pennsylvania, and the work that was cited in Frazier’s 2015 MacArthur fellowship. Many of the photos on view here are intimate interior shots of several generations of Frazier women (bathing, hanging out, falling asleep in front of Lifetime television) and their belongings (collections of porcelain dolls, knickknacks, and many photos). The ubiquitous presence of photographs in Grandma Ruby’s home suggests their central role for the family—as both record and livelihood. Rooms are crowded with pictures (including Frazier’s prints) framed, taped to walls, and curling on the fridge. The same images crop up again and again in the background of Frazier’s photos for the project, as if refracted in a mirror. (In one group portrait, Frazier shoots directly into an actual mirror, further underscoring this proliferation of images.) Other pictures, such as a 1990 Kmart family portrait, are re-photographed at scale, collapsing any categorical hierarchies as to who is taking the picture. In The Bedroom I shared with Grandma Ruby (227 Holland Avenue) (2009), shot after Grandma Ruby’s death, a small, empty room has reverse shadows on the wall—pristine white squares in different sizes, sometimes a little crooked—where pictures once hung. After the packed views of Grandma Ruby’s home, this emptiness is jarring, as if the missing photographs had been a part of her presence.

Frazier’s images form a sort of living archive—and one with many contributors: she began The Notion of Family when she was a teenager, collaborating with her mother and grandmother, who also took pictures for the series. (She considers their trio to be “one entity,” and it’s clear that her whole family is instrumental in creating a notion of itself.) In addition to the ambitious scope of her projects, Frazier’s approach feels generous; her images seem to accentuate the ways that her subjects have worked to maintain their own presence and autonomy well before she showed up with a camera. (Her photographs of family photographs also exemplify this.)

Frazier’s work emphasizes the fact that photography, a process of exact reproduction, is reliant on what it pictures for what it is. Every photograph is, in this sense, a collaborative effort—made not just by the photographer but also by the photographed. In handing over her camera to her mother, or having Shea’s story dictate the scenes photographed in Flint, Frazier adroitly channels this truth about photography’s collaborative nature into further inclusiveness, particularly in the documentation of the African-American family. Wresting narrative authority away from a single, privileged role of “artist” or a single, privileged school of theory, Frazier boldly stakes her presence in photography’s history on her own terms. As she put it, “My mother did not have to read Camera Lucida to understand death in a photograph.”

The show ends with a note of transcendence on the top floor. The landscape is suddenly expansive and unpolluted in A Pilgrimage to Noah Purifoy’s Desert Art Museum (2016–2017), thirteen four-by-five-foot photographs, drenched in sun and shadow, of Joshua Tree and the magical ten-acre art space built there by the late African-American artist. Purifoy’s dozens of sculptures and structures were partly assembled out of burned materials he’d salvaged from the Watts Riots in Los Angeles in the 1960s, as Frazier explains in the exhibition’s materials: “He took these things—these pieces of wreckage—and turned them into works of art, a meditation on one’s life, one’s work, one’s history.”

“LaToya Ruby Frazier” is at Gavin Brown’s enterprise through February 25.