In 1858, Abraham Lincoln launched his campaign for the Senate seat from Illinois with his now famous “A House Divided” speech. While he did not predict disunion or civil war, Lincoln alluded to the country’s deep political divisions over slavery and concluded, “I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.”

Even before what historians call the political crisis of the 1850s, the rise of an interracial abolition movement had encountered mob violence in the streets and gag rules in Congress. From then on, abolitionism in the United States was tied to civil liberties and the fate of American democracy itself. By the eve of the war, in 1861, most people in the northern free states felt that the democratic institutions of the country were being subverted.

There are many Americans who feel the same way today. Some have pointed to the glaring, and growing, partisan divide in the US to conjure doomsday scenarios, including “civil war.” How does our own epoch of fierce political polarization compare to the decade that was rent over the issue of slavery before the Civil War? Predictions are often overwrought and historical analogies can be misleading, but the controversies that bedeviled that age and its legacies still haunt us. In certain ways, they foreshadow—or, perhaps, still condition—our own divided house.

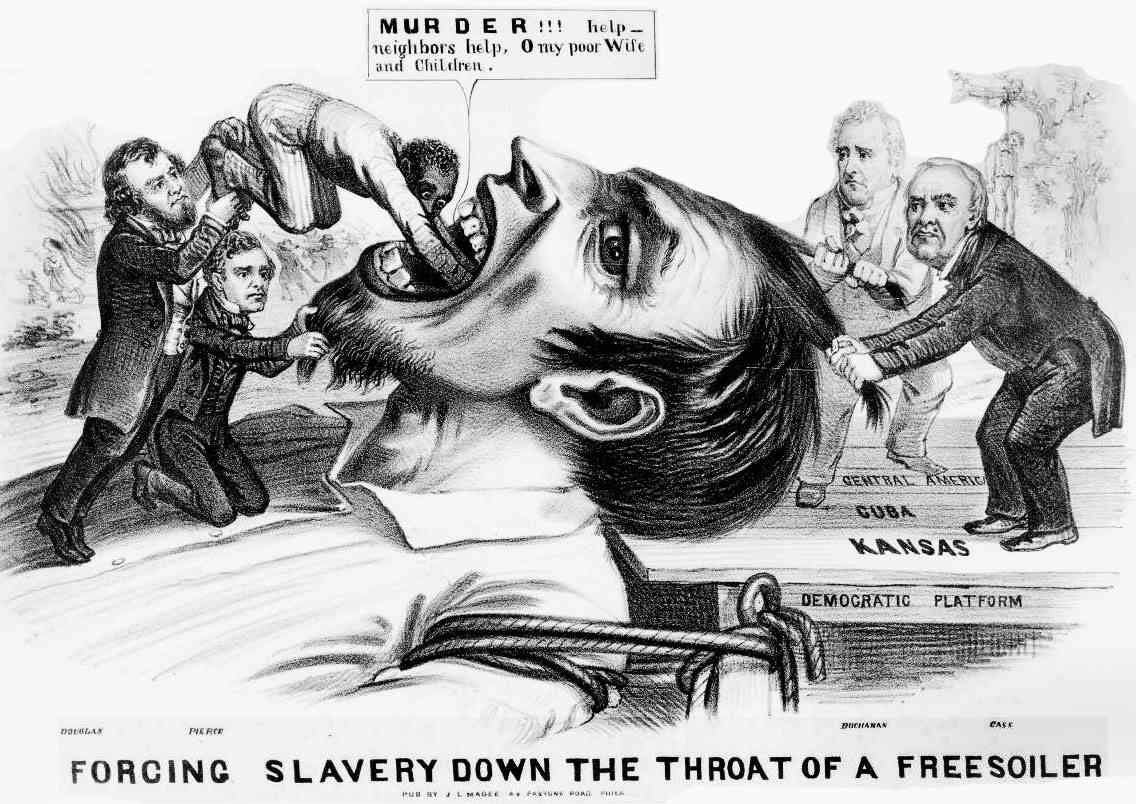

In 1850, the passage of a draconian federal Fugitive Slave Law not only imperiled black freedom, but also threatened the rule of law and due process in the North. During the Kansas Wars of 1854–1861, which were, in hindsight, a dress rehearsal for the Civil War, proslavery ruffians from Missouri regularly invaded Kansas to steal territorial elections and push through the legalization of slavery—contrary to the wishes of a majority of the territory’s inhabitants. Finally, the Democratic-controlled federal administration tried to force on Kansans a proslavery state constitution, representing the interests of just 10 percent of the territory’s population. That attempt failed, but even northern Democrats realized that the white man’s democracy could break down over slavery.

The controversy also took a violent turn. Abetted by their state governments, southern slaveholders had long restricted freedom of speech and of the press, as well as prescribing medieval forms of punishment for those accused of advocating abolition, including public whippings and imprisonment. In 1837, a pro-slavery mob had murdered the abolitionist newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy as he defended his press in Alton, Illinois. It shocked the North when, in 1856, the South Carolinian Congressman Preston Brooks caned the anti-slavery senator from Massachusetts, Charles Sumner, for giving an abolitionist speech. By that time, many northerners, especially abolitionists, were ready to respond in kind: there was open warfare in Kansas between emigrants from slave states and free states, and fugitive slave rebellions throughout the North to prevent the rendition of runaway slaves. Such conflicts culminated, famously, in the raid at Harper’s Ferry in 1859, John Brown’s attempt to start a slave rebellion.

None of these actions, however, led directly to the South’s secession and the Civil War, although they sharpened the country’s sectional divisions over slavery. There were many other moving parts involved in the political disarray of the 1850s. One was the collapse of the so-called second-party system, in which each of the main political parties comprised of northern and southern wings were bound in a complicated alliance of forces. Another was the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment. While Lincoln’s party, the Whigs, disintegrated under the weight of the sectional argument over slavery, the nativist Know-Nothing party took its place in many states, North and South. Lincoln memorably stated his position in 1855:

I am not a Know-Nothing. That is certain. How could I be? How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it “all men are created equal, except negroes.” When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read “all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.” When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocracy [sic].

In our time, the surge of anti-immigrant sentiment in the US, exemplified by Republican support for Trump’s plan to build a border wall, has resurrected this ugly, persistent strain in American politics. (It is interesting to note, too, that even in Lincoln’s day, Russia made itself felt as a political presence, a rival model to American democracy.) Today’s efforts to obstruct immigration and citizenship for Dreamers have a precedent in the nativist Know-Nothing party’s initiative to restrict the path to citizenship for the large waves of immigration of the 1850s. Under the Trump administration, the Citizenship and Immigration Service has changed its mission statement from safeguarding “America’s promise as a nation of immigrants” to promising enforcement of the nation’s immigration law.

Advertisement

Anti-immigrant politicians in the Republican Party like Congressman Steve King of Iowa are even eager to undo national birth-right citizenship that was originally mandated by the Fourteenth Amendment to enfranchise former slaves. And in our time, immigration activists and the sanctuary movement have looked to the abolitionists’ defiance of fugitive slave laws and resistance to the federal marshals who implemented them to counter, with grassroots activism and legal strategies, the Trump administration’s immigration directives and the actions of ICE agents. The punitive separation of children from parents under ICE detention evokes the cruelty of ripping apart black families long settled in the North through the enforcement of fugitive slave laws.

Unlike today, though, slavery proved to be a fault-line that overrode every other political division and difference. Eventually, the Know-Nothing party itself would break up over debates about slavery; it was replaced, in part, by the rise of the antislavery Republican Party, based primarily in the free states.

We need to reverse everything we know about the Republican and Democratic Parties today when we talk about the mid-nineteenth century. In the third-party system that emerged during the 1850s, Lincoln’s Republican Party was liberal on slavery and the political rights of black Americans. The Democratic Party was the party of southern slaveholders and their conservative northern allies, known as “doughfaces” (northern men with southern principles); it was thus the party of slavery, white supremacy, and states’ rights. Writing to his estranged father in New York, Oscar Lieber, who would die fighting for the Confederacy, argued that the South had more in common with Cuba, where slavery was still legal, than with the free North.

Like most northerners and southerners who could vote in the 1850s, Republicans and Democrats today can seem to inhabit different universes with fundamentally opposed values, mores, and tastes. (According to one recent survey, most people who expressed support for one party would not want to marry a person who backed the other.) Southern pro-slavery ideologues charged that atheism, socialism, feminism, anarchism, and “niggerism” would overthrow all class, race, and gender hierarchies. Even as the Republican Party today has adopted the platform of states rights and laissez-faire capitalism, the Democratic Party has adopted progressive politics and a social liberalism that they decried a century earlier. The reactionary politics and religious fundamentalism of southern slaveholders finds an echo among the political flat-earthers of our time, those who deny science, history, and reason, and instead believe in all manner of lurid conspiracies.

In recent years, graphics that transpose maps of the partisan divide in Lincoln’s 1860 election on recent presidential election maps have become popular memes. Finer-grained electoral maps reveal a more complex picture, both at the county, urban, suburban, and rural levels in each state, and between the more cosmopolitan East and West Coast states and the vast, though less peopled, interior and South. Notwithstanding the emergence of purple states, partisan divisions have hardened.

In a four-way contest in 1860, Lincoln won both the popular vote and the electoral college decisively. After Lincoln was elected as the first Republican president, following a decade of northern doughface presidents and Democratic control of the federal government, seven Lower South (the cotton states of the Deep South) states seceded rather than accept the result of the election. For Lincoln, the war became tied to the emancipation of slaves and the survival of American democracy, as he famously outlined in the 1863 Gettysburg Address. We may not be in the midst of a war today, but the progress of democracy in this country is still tied to the rights of its most vulnerable citizens.

Secessionism’s unprecedented assertion of state sovereignty, based on a profoundly racist and anti-democratic response to the election to the presidency of a “Black Republican,” as the slur used by southerners and Democrats put it, is still visible in the political reflexes of the American right. The notion that some people are inherently less worthy of the right to vote underpins continuing attempts at voter suppression and political gerrymandering by Republican officials. One can trace that legacy right back to the notorious Dred Scott decision of the US Supreme Court in 1857, in which Chief Justice Roger B. Taney pronounced that a black man had no rights that a white man was bound to respect, an idea that continues to infect the policing and mass incarceration of African Americans today. The ruling provoked Lincoln’s memorable condemnation of slavery that echoes to this day:

Advertisement

All the powers of earth seem rapidly combining against him. Mammon is after him; ambition follows, and philosophy follows, and the Theology of the day is fast joining the cry. They have him in his prison house; they have searched his person, and left no prying instrument with him. One after another they have closed the heavy iron doors upon him…

In the decade before the Civil War, southern secessionists had called for the re-opening of the African Slave Trade, demanded a federal slave code, hatched schemes to illegally invade Cuba and re-introduce slavery in Nicaragua. But how does the extremism on the issue of slavery in the Democratic Party of the 1850s compare to the extremism today of gun rights advocates, religious fundamentalists, and our present-day corporate robber barons allied to the Republican Party? By the end of the nineteenth century, the Republican Party had been transformed from the party of antislavery to the party of big business. Today’s GOP has married the regressive politics of the nativists and the slaveholders of the 1850s with the excesses associated with the Gilded Age.

The extreme-right positions of the modern Republican Party—opposition to gun control and tax breaks for the one percent that will take us back to the 1920s, not to mention endemic racism and misogyny—are reminiscent of the aggressive slave power of the 1850s that was drunk on its own certitude and arrogance. In the end, some northern Democrats bolted from their party because of the intransigent demands of slaveholders. Aside from a handful of #NeverTrump conservative intellectuals, we are still waiting for a substantial section of decent Republicans to disavow the openly racist and nativist sentiments, enflamed by the president, of their political base.

In the face of slaveholder extremism, Lincoln made an eloquent appeal to southerners in his first inaugural address to realize “the better angels of our nature”—a spirit of unity that Barack Obama invoked in his 2008 victory speech: “As Lincoln said to a nation far more divided than ours, we are not enemies but friends. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection.” Those bonds were soon broken in 1861. Within little more than a month, the Confederacy had fired the first shot at Fort Sumter, leading to the secession of four Upper South states and beginning a long and fratricidal war in which 750,000 Americans lost their lives—more than all the major wars fought by the United States in the twentieth century.

Under Obama, modern red-state Republicans did not threaten to secede from the Union as the southern slaveholders did, but their representatives seceded from all political cooperation in Congress, bitterly opposing the administration to the end. Both Lincoln and Obama were mercilessly race-baited. Lincoln was called “Abraham Africanus I” and “a general agent for negroes.” One secessionist alleged that Lincoln’s dark-skinned vice president, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, was a “mulatto” and had African blood. Shocking and crude insults against the Obamas, picturing them as monkeys and the like, were circulated by members of the party’s more unregenerate base. Right-wing talk radio hosts fed the fantasy that President Obama was an interloper—a secret Muslim not born in the United States. A self-appointed leader of the “birther” movement occupies the White House today.

For more than a century after the Civil War, the party of Lincoln was identified with emancipation and the rights of blacks. The transformation of the slaveholding republic into an interracial democracy during Reconstruction briefly realized African-American and abolitionist hopes. The violent overthrow of Reconstruction and the institution of a brutal racial regime of disfranchisement, segregation, sharecropping, and racial terror in the South—or “home rule” and states’ rights for southern whites—was a tragic counter-revolution.

The political realignment that began in the New Deal era and was reinforced by the civil rights movement and the GOP’s subsequent “southern strategy” led eventually to the present-day partisan divide over government, race, and the economy. African-American voters defected wholesale from the Republican to the Democratic Party, and the “Solid South” of the old Democratic Party that did not give Lincoln a single electoral vote contains the reddest of red Republican states today. (To see the continuities, look no further than the efforts to rewrite the history of slavery as the last time America “was great” by Roy Moore, the Republican candidate in Alabama’s special election for the US Senate.) After the Obama presidency (when, in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s words, We Were Eight Years in Power), the country has witnessed a resurgence of racial prejudice, sexism, and anti-immigrant sentiment, and a reassertion of the political economy of robber barons.

Beneath the weight of this history, it is little wonder that today’s struggles over the status of Confederate monuments and political demonstrations by avowed white supremacists evoke anxieties about disunion. We would do well to pay heed to the old enmities bubbling up in our politics: it is not that we are on the verge of another civil war, but that the Civil War never truly ended. With the exception of slavery itself, what divided the United States then divides us still today. As Lincoln warned, in his famous letter to James Conkling about those who opposed black emancipation and recruitment into the Union Army:

And then, there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they strove to hinder it.

An earlier version of this essay misstated how many southern states seceded in the first instance after Lincoln’s election; it was seven, not nine (the final total of Confederate States was eleven).