In response to:

To the Whitehouse from the February 1, 1963 issue

To the Editors:

Perhaps it might be well to point out to your readers that the sentence in The Politics of Hope which led Dwight Macdonald to a long paragraph of lamentation over my moral and political condition was nothing more than a gloss on the quotation from Thomas Jefferson which immediately preceded it: “To lose our country by a scrupulous adherence to written law, would be to lose the law itself, with life, liberty, property and all those who are enjoying them with us; thus absurdly sacrificing the end to the means…. The line of discrimination between cases may be difficult; but the good officer is bound to draw it at his own peril, and throw himself on the justice of his country and the rectitude of his motives.”

Now there are no doubt those who dismiss Jefferson and join with Macdonald in saying that it is more important to save the letter of the law than to save the nation. But it seems a little extreme to suggest that those who disagree with Macdonald and agree with Jefferson on this matter are necessarily, as old Dwight implies, wicked, un-American or even illiberal.

If Macdonald is going to continue to write about American history, I wish someone would tell him that the remark “he made his law; now let him enforce it,” if ever said at all, was said by Jackson about Marshall, not by Lincoln about Taney (whose name, both Mr. Macdonald and the editors of The New York Review might note is not spelled “Tawney”).

ARTHUR SCHLESINGER, JR.

Washington, D. C.

DWIGHT MACDONALD replies:

That’s quite a gloss that Mr. Schlesinger (young Arthur) has glossed on Jefferson’s truism. Let me write a nation’s glosses and I care not who writes its laws—assuming any are left. I agree with Jefferson (old Tom) that “to lose our country by a scrupulous adherence to written law” would be folly, and I disagree with the formulations that young Arthur has glossed into my mouth: “It is more important to save the letter of the law than to save the nation.” Of course it isn’t. The political—as against the debating—point is not whether one would choose to sacrifice the law in order to preserve the republic of which the law is an expression, but rather what are the grounds on which one decides such a choice has become necessary. “The line of discrimination between cases may be difficult,” Jefferson writes, but Mr. Schlesinger makes it sound as easy as falling off a log called the Constitution. In my declining years, I have come to have a great respect for that ancient document for somewhat the same reason the frogs came to prefer King Log to King Stork: it may not be very dynamic but it does, occasionally, protect us against the storkish aggressions of an authoritarian Executive and a majoritarian Congress.

The Schlesinger gloss on Jefferson to which I objected was: “The Executive…should not be able to abrogate the Constitution except in the face of war, revolution or economic chaos.” There is no space here to go into the semantic and historical questions that are raised by a second look at this apparently harmless formulation, but I hope to expatiate in the next issue. Meanwhile, let me thank Mr. Schlesinger for correcting me on the spelling of Chief Justice Taney’s name and also on the attribution of that damaging quote to Lincoln. It was sporting of him to substitute his own very first Heroic Leader, whose respect for our Constitution was even more moderate than Lincoln’s. I was writing from unprofessional memory and should have looked it up. However, I shall impenitently “continue to write about American history” as long as Mr. Schlesinger continues to write about movies. And perhaps a bit longer.

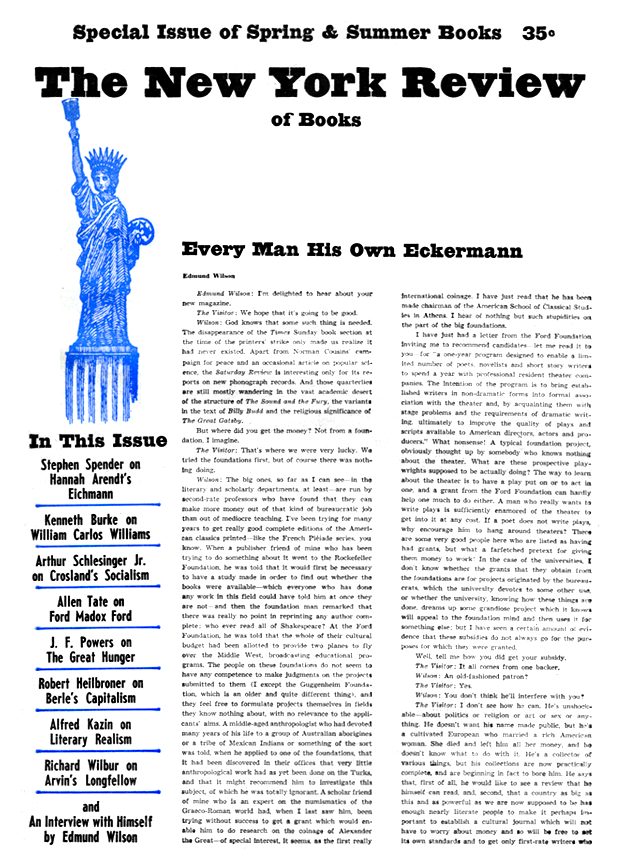

This Issue

June 1, 1963