“Realism” is a boring term now, fit only for textbooks. There are people who still use it with interest. But these are either literary scholars, who are concerned with the history of ideas, the history of forms, the history of a common way of seeing reality (which is what a literary movement represents)—or propagandists for art-with-a-purpose. No intelligent novelist worries about “realism” any more; what it stood for in the 19th century has long since been absorbed into even the most indifferent and machine-produced literary entertainment for the masses. And when “realism” is used to denote a positive ideal, as it is by people more interested in sociology than in literature, it is difficult to repress one’s indignation at the thought of what “realism” in the Soviet Union, where it is not a literary creed but the state religion, has done to honest writers.

Why then bother with “realism” today? Why read and review an anthology of this bulk, laden with thoughts on realism by all those 19th-century writers, Russian, French, German, Italian, Spanish, English, American, for whom “realism” was a lively issue? The answer is that the interest in “realism” has been an interest in the novel. The novel is nothing without “real life”; the novel has always, whether supported by “realistic” doctrine or not, been synonymous with realism; the novel, even in our day, when so many literary minds are expressly against realism as a doctrine, seems to break down whenever there is not vital enough or consistent enough a sense of “reality.” Even the most pretentious and boding epistemological French novelists of the new wave don’t seem to be able to write fiction or even to talk about fiction except in relation to “realism.” For realism and the novel grew out of the same need to describe and indeed to systematize our literary ideas of the external world. Realism and the novel had the same roots in the “modern,” sceptical, thing-concerned instrumentalist world. Works completely “romantic” are not novels, they are romances; no matter how much there is of romance in a novel by Cooper or Scott or Melville, the relationship to the agreed-upon and sensible external world is unmistakable.

It is true, as Professor George Becker says in his comprehensive introduction to realism as a movement, that “realism rarely, if ever, dominated and controlled a whole work before the middle of the 19th century; rather it was controlled and its functioning directed by the official aesthetic doctrine of a given time and place, which was never before realistic.” But the novel with its peculiar openness—to the life of crowds, groups, streets; to erotic detail; to adventures and journeyings; to low life; to thieves and prostitutes; to politics, scandal, war, the stock exchange, the factory, the fields, the labor exchange, the hiring hall—would never have emerged as the great modern form, the almost inevitable destination that prose takes whenever it wants to make things really explicit by dramatizing them, if it had not emerged from the same interests and beliefs as “realism.”

Of course the novel is a form and “realism” is a formula. But the deepest interest of the formula is surely what certain “seizing” imaginations (to use a key word in Henry James’ writings on the novel) made of it. Just as there are textbooks of “realism” in American philosophy which no one not a a professor would ever open if they didn’t feature William James or Santayana, so no one who just cares for literature would today, when there is obviously no need for realism as a doctrine to be an explicit and fighting issue, pay any attention to “realism” if it weren’t for the fact that without it Stendhal, Balzac, Tolstoy, Flaubert, James, Crane, Dreiser and other pillars of the modern novel might never have created their works.

Does it matter, then, that Dickens is not a full-fledged realist? That in his preface to La Comedie Humaine Balzac is grandiloquent in his conception of it and that Zola, in Le Roman Experimental, simply mechanical and pretentious?

Yes it does—it matters not in relation to the doctrine, which like all literary doctrines is simply an agreed way of looking at reality, a “truth” good for a season, but in relation to the imaginations that are inspired by it. For me “realism” is something that Balzac believed in, or thought he believed in, and made use of as if he believed in it. It was a creed, undeniably pretentious, even in his hands obviously stretched to suit his imperial temperament, but which nevertheless gave him a convincing picture of things, an idea with which to unlock the voluminous 19th century. The fact that Flaubert didn’t really consider himself a “realist,” that he indeed resented and despised the doctrines and dictionaries of the movement, doesn’t remove the fact that if realism hadn’t been in the air, if Flaubert hadn’t forced himself to participate in it “once,” as he said grimly, Madame Bovary would not exist. Of course it is comic now to read the reviews of the time in Professor Becker’s anthology and to learn that Bovary is “arid” and “dry.” Today it is impossible to read the most beautiful passages in the book, like Emma unfurling her umbrella in the rain, without feeling a kind of compassion for Flaubert, still hungry for “beauty,” and indulging himself in colors and textures as if they were forbidden sweets. But it is less the inconsistency of “realistic” method in Flaubert that interests me now than it is the variations in tone. These proceed, I suspect, from Flaubert’s impatience for effect, from the extraordinary personal bitterness from which he was always trying to escape into the effects of brutality (which he called “objectivity”) and beauty. Flaubert was never really objective at all, since he despised the public world and wanted either to escape it or to parody it.

Advertisement

Realism-naturalism was a springboard to the creative imagination. Despite the lack of purpose in the universe that such doctrines announce, no writer ever feels that a doctrine is without purpose if he can make use of it. When a man says that life has no fundamental purpose and that his aim as a writer is “merely” to show the objective facts of behavior, he takes advantage of the supposed meaninglessness and objectivity to show how free, clever and dynamic he is in discovering these profound truths. So long as men live in time and can anticipate a future, they will make use of ideas, even ideas of purposelessness, to display their discovery of truth. The Count de Vogue, a section of whose remarkable book on Le Roman Russe is included in this anthology, complained, as so many thoughtful Christians did in the 19th century, that realism-naturalism was a denial of meaning and purpose in the universe. But when a writer himself says, as Zola did, that novelists have become scientists, that the novelist now performs “experiments” on his characters, that the “experimental” novel, as he called it, “is simply the record of that experiment,” that “the whole experiment consists of taking facts from nature,” how can we believe that Zola is a mechanism, that Zola is anything but a free and creative human being proud of having found his key to the mystery of nature and society? Nietzsche understood—Erich Heller quotes this in his essay here on “The Realistic Fallacy”—that “realism” in art is an illusion, that all the writers of all the ages were convinced that they were realistic…. “What then,” asked Nietzsche, “is it that the so-called realism of our writers tells us about the happiness of our time?…. One is indeed led to believe that our particular happiness does not spring from what really is, but from our understanding of reality…. The artists of our century willy-nilly glorify the scientific beatitudes.”

Nietzsche, who was more penetrating than perhaps any novelist of his time except Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, and despite his private instability actually more balanced a mind than either, was no doubt right to see “realism” as the artist’s key to understanding, a form of intellectual control and mastery—indeed, of overwhelming pride. But Nietzsche, who even as a philosopher was unique in his disdain of system, understood better than most philosophers—he was probably the most gifted “poet” among the philosophers after Plato—the relationship of any philosophy to imaginative creation. Dante’s cosmogony, which we consider mistaken, does not keep us from appreciating his poetry. Many a point of view which we in our day consider absolutely true, irrefutable, sensible, going to the heart of things, nevertheless has not added a good line to a poem, made a character live in a story and shaped a beautiful line in any piece of writing. Yet to write at all, one must see the world in some comprehensive light; one must see it so for oneself. Whether the character a writer gives the world will fit in well with the present age or be superseded by the next, the writer must give a character to the world he lives in—from its streets to its cosmos. He must believe in the image of reality he uses. He must really see things in its light.

“Realism” did this, passingly and scatteringly, for certain novelists in the 19th century who wanted to give direct impressions of life. Life had opened up even more than the novelists had. Realism liberated gifted people in the lower class to discover their vocation as novelists. If it hadn’t been for realism, all writers would have had to come out of the old elites; like the French revolution, industrialism, democracy, big cities, “realism” opened the way to new talents. Of course many such writers, notably Zola and Dreiser, were intellectually pretentious. They posed as thinkers, but were merely novelists.

Advertisement

Obviously this was not a loss; and in any event “realism” as a way of interpreting reality soon became banal, programmatic and even cheap. As an authentic philosophy it fell apart in the 1890s, when imaginative new thinkers like William James, Freud and Bergson put a new emphasis on the autonomous and unconscious resources of the individual. By now this, too, as a way of seeing human beings for purposes of imaginative form, has become so banal and second-hand that it is impossible to imagine works like Ulysses and The Sound and the Fury coming out of the Freudian clichés of our day. It may be that “creeds” in general are now mistaken by the writer as tyrannical and external; changes in the external world, which in the 18th and 19th centuries the novelists felt exactly suited to describe, now proceed too fast for everybody except computers. When one considers how confidently and rhythmically the novelists of the past advanced in order to display their mastery of “fact” in the external world, it is not hard to see why novelists do less well than they used to. They simply don’t know how to put so much change into their books, and though they try to look back, now, to the “age of psychology” as to a golden age, it is clear that the psyche is not of limitless interest as a subject for fiction. Yet “realism” as a way of thinking, as an approach to what we confidently still think of as “reality”—outside of us yet still embracing us in a single order of truth—will remain so long as fiction remains the natural extension of an age of prose.

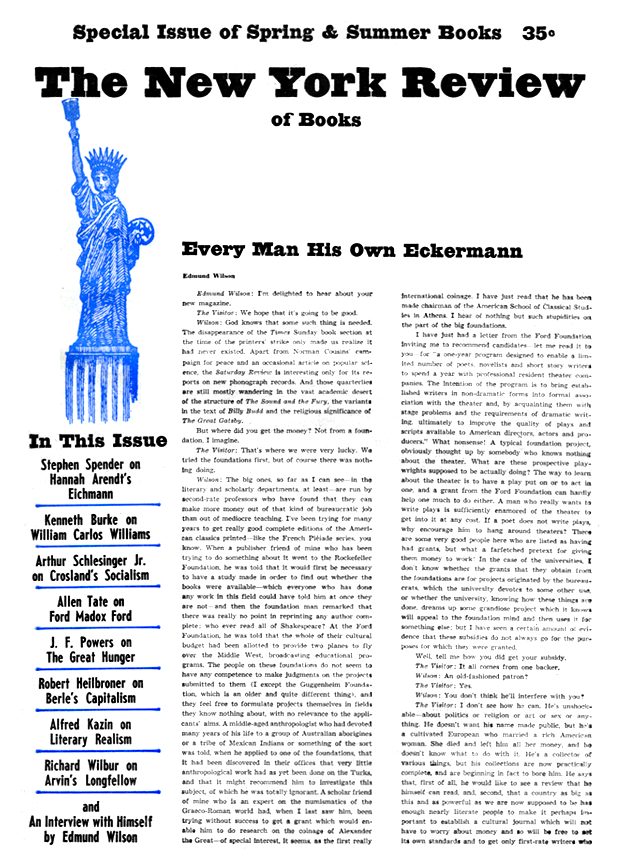

This Issue

June 1, 1963