“You forget, my dearest Love, that I am the Sovereign.” This is how a girl of twenty wrote to the young man she was about to marry. The candor is stunning. Some have found it disarming, but perhaps they also forget that Victoria remained the Sovereign for no less than sixty-four years, in much the same frame of mind. These letters, covering the first part of her reign up to the death of the Prince Consort, produce a chilling effect. The imperiousness of fat-cheeked Little Vic soon loses its charm. By 1862, she looks more like a little tyrant.

Today, the British Royal Family has become supercilious about other monarchs. Sinking gradually into attitudes more upper-middle-class than royal, Buckingham Palace seems to have accepted one of the most insular snobberles: that all foreign dynasties are fake ones. The smile which greets a visiting king is wary rather than cousinly. But for Queen Victoria, the crowned heads were a great big family, a crowned trades union, a royalist international. She winced and fussed when the least royal sparrow fell, when some syphilitic margrave was deposed for firing his butlers from cannons, when some rustic kinglet expired after a surfeit of cold rice pudding. They all belonged, and their eclipses all darkened her own light.

This was an unlucky feeling to have in the century of nationalism and republicanism. Yet it remained central in Victoria’s attitude to politics. She could even develop a housemaid’s crush on the senior king of all, Tsar Nicholas I. “Really, it seems like a dream when I think that we breakfast and walk out with this greatest of all earthly Potentates.” Goggling, she took the great tyrant round the grounds at Windsor. “How many different Princes have we not gone the same round with!!” Also present was “the dear good King of Saxony,” who pottered about dimly. Victoria’s references make him sound like an idiot child: “He is so unassuming. He is out sightseeing all day, and enchanted with everything.” Throughout the revolution of 1848, Victoria was “so anxious for the fate of the poor smaller Sovereigns, which it would be infamous to sacrifice.” One notices the patronizing “poor smaller Sovereigns,” as one notices her uncritical obsequiousness to the Tsar: between beggarly curates and the Archbishop, Queen Victoria was like the wife of a well-nourished dean in a senior cathedral close.

These were the years of her quarrel with Palmerston. A long and inconclusive dispute ended with the Queen coming to terms with her Minister, though never with his outlook. But the hero of the whole exchange was beyond doubt Lord John Russell.

Events assumed a pattern. Lord Palmerston, as foreign secretary, would draft a despatch saluting a new revolution or calling some unreconstructed foreign big-wig “a notorious defaulter to the amount of 200,000 drachms.” The Queen would accuse him of inconsistency and warmongering, and require him to change the text. Lord Palmerston would then turn out to have already sent off the original. The Queen would request Lord John Russell to remove Palmerston instantly from office. And then Lord John would go into his masterly, unctuous, regretful act of pretended impotence: Lord P. could not be excused—naturally—but he was so popular, so influential; one could not risk “turning him against the government” and so on, and so forth. At the price of appearing too weak to control his own subordinates, Russell kept Palmerston in office and Britain on a boldly liberal course in foreign policy until in 1851 Palmerston did something which was not only reckless but also anti-liberal: he gave effective recognition to the coup d’état of Louis Napoleon without consulting his colleagues or the Queen. He fell, only to return four years later as Prime Minister.

From these letters, there emerges nothing essentially “constitutional” about Queen Victoria’s attitude to her job. She was not given an education for monarchy, and learned only empirically from men like Lord Melbourne and the devoted Baron Stockmar from Coburg. She came to understand that there were certain things she could not do, but there is no sign that she ever accepted reasons why she should not do them. Much has been written about the influence on her of Leopold I, first King of the Belgians, her uncle and, through innumerable letters, her counselor on the duties of a queen. But it emerges quite plainly from this book that much of his advice just didn’t apply to the British situation. In Belgium, he had accepted the throne of what was practically a republic, a state with a carefully written constitution which limited his powers closely. Yet, with politics still molten in the new Belgian parliament, Leopold found himself acting as the country’s political leader; he had to put ministries together, he had to run foreign policy, he had at all times to stop the parties from taking up extreme attitudes which would endanger Beigium’s very existence. Britain did not need or want this sort of parental care. The last thing Parliament and the party leaders wanted was royal initiative in political matters; they were tough enough to fight their own battles. In those battles, of course, the loyalty of the Crown to the existing ministry was a useful weapon. But the loyalty of the ministry to the Crown was only to be assumed, not put to practical use.

Advertisement

Leopold, who had nearly become a Prince Consort of Britain himself, had bitter views about the national hypocrisy towards things moral and constitutional. “…the very state of its Society and politics renders many in that country essentially humbugs and deceivers; the appearance of the thing is generally more considered than the reality… Defend yourself, my dear love, against this system …” But this she was not able to do. The reality was the confident supremacy of Parliament, which already in effect required her to speak only when she was spoken to.

This did not prevent her from forming close friendships with her prime ministers. The almost passionate relationship of the young girl with Melbourne is covered in these papers, though Disraeli’s courtship falls too late to be included. And one is reminded that the professional politician in Britain—now as then—has to strike a pose not only before his electorate but before his monarch. With grotesque relish, statesmen threw themselves into charades of entreaty, abasement, humble reluctance, even of implicitly sexual enslavement (as the first Elizabeth’s ministers had done, and as Disraeli was to do). The Queen, they suggested as they groveled enthusiastically, was an exquisite autocrat, a tender little tyrant. The dungeons of the Tower of London, they implied, yawned for them if a frown crossed the angelic forehead.

All this was humbug with frogs and epaulettes on. They managed the Queen without serious bother, but had themselves a wonderful time pretending to chivalry. “I would waive every pre-tension to office, I declare to God! sooner than that my acceptance of it should be attended with any personal humiliation to the Queen,” lied Sir Robert Peel, as he forced Victoria to fire her Liberal ladies-in-waiting. In almost every Victorian politician there lurked a tearful masochist. The fact that the monarch was a woman brought it out. Did Mr. Macmillan and Mr. Butler and Lord Home shed crocodile tears with the Queen last month, as they exhibited to her majesty the blatant, rampant fact that they were going to force a new prime minister on her? One would love to know.

But it was lucky for Britain that Victoria could not have her way. She was despotic, without much intellectual enlightenment or even a vision of becoming a “poor people’s Queen,” and forming an alliance of the masses and the Crown against the upstart middle classes. She believed in power for herself, and protection for property. For the rest, charity. She approved the repeal of the Corn Laws because it removed the danger that “we would have been forced to yield what has been granted as a boon.” Her favorite environment was the depopulated, landlord-wrung background of the Highlands, where the survivors showed picturesque qualities of independence.

So one comes, with relief, to the character of Albert. Here at last is an educated person, and a sincere one. At the height of the anti-Chartist hysteria, on the very day in 1848 when their London rally was expected by the middle classes to ignite a revolution, Albert could write to the Prime Minister blaming unemployment for the discontent and criticizing the government for laying off builders on public works. He understood perfectly the constitutional set-up, and mediated like a Hammarskjold between Victoria and her ministers. Perhaps the opening of his Great Exhibition, at the Crystal Palace, really was “the greatest day” in British history, as Victoria wrote two days afterwards.

Victoria’s own attitude to Albert is the most extraordinary element in these papers. Extravagantly fond (“my dearest Angel”), she was still shockingly proprietary about him. Leopold I had produced him, and her grateful letters to Leopold make Albert sound like some wonderful household appliance. Albert is still running beautifully, gives not a moment’s bother, and I really don’t know what I would do without him. Even when he died, Victoria’s grief has in it something of regal fury: Fate, that Palmerstonian scoundrel, has gone behind her back and stolen her happiness.

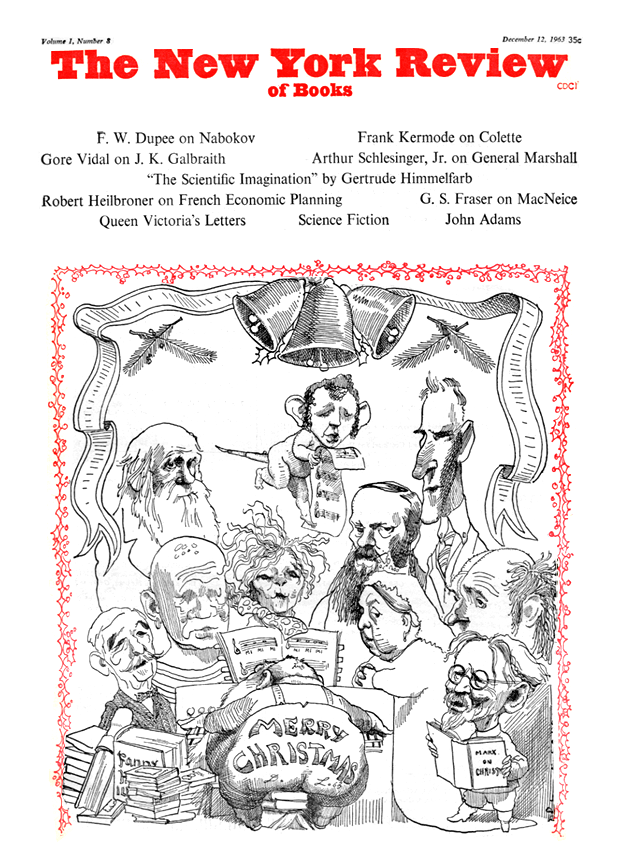

This Issue

December 12, 1963