Though Gallic wit will always continue to flourish even if it is driven underground, it has become increasingly hard to seek in modern French literature. Possibly this may be due to the last war: a heavy pall of bleak pretentious boredom has descended—one hopes only temporarily—on the purveyors of contemporary fiction. The recent winners of prominent French literary prizes reinforce a suspicion that these are allotted by masonic agreement between publishers and critics. Politics may also play its deleterious part, and the personal magnetism of such avantgarde exponents as M. Robbe-Grillet and M. Le Clézio, but the Muses are seldom present at the coronation. The prizes insure a large sale, if not an enduring reputation. The crowned novels are read, or rather skimmed, in a spirit of curiosity by a public eager to keep abreast of the times. How many readers are doomed to disillusion! Surely never before has there been such a spate of pompous drivel parading as creative literature. Let us then be all the more grateful to M. Roger Peyrefitte, who upholds the virtues of crystaline lucidity, barbed wit, subtle insight, observation, and elegance of style which have distinguished the best French writers in the past. These virtues even percolate through translation, though le mot juste is most difficult to render.

M. Peyrefitte is a peculiarly French phenomenon, for one can think of no parallel in other countries. In England he would become involved in endless lawsuits; behind the Iron Curtain he would be liquidated. He collects violent protests instead of literary prizes, in fact he thrives on them. His books, which grow longer, bulkier, and more expensive, continue to sell like hot cakes in spite of being so well written. Their subject may be scandalous, but not his treatment of it. His language is never coarse. Schoolboy passions have seldom been described with such delicate sympathy and understanding as in his Special Friendships. His Death of a Mother is another haunting document which all psychologists should read. In these earlier novels M. Peyrefitte’s seriousness is more apparent than his wit. Diplomatic Diversions, on the other hand, is a rollicking satire on the antics of certain pre-war diplomats. Here his wit is paramount, but I confess I have not read it in translation. Several of his older colleagues still turn purple when Les Ambassades and La Fin des Ambassades are mentioned, but in strict confidence they are bound to admit the underlying truth of his observations. Greece strengthened his devotion to Hellenic culture during his fruitful period in the diplomatic service. His translation of The Loves of Lucian of Samosata reminds one of his kinship with that pioneer satirist, who wrote that the historian should be “fearless and incorruptible, independent, a lover of frankness and truth…indulging neither hate nor affection, unsparing and unpitying, not shy nor shamefast, an impartial judge….”

In middle age he remains an enfant terrible who delights in provoking the Establishment. Sometimes he suggests a learned Jesuit; at others (as Auden said of T. S. Eliot) “a twelve-year-old boy who liked to surprise over-solemn wigs by offering them explosive cigars.” In his later novels, beginning with The Keys of St. Peter and ending with Les Juifs, wherein he maintains that most of us, including General de Gaulle, are of Jewish extraction—a book which has kindled the fierce resentment of the Rothschild family and not a few literary colleagues such as Marcel Jouhandeau—one cannot be sure where fiction ends and history begins; for he combines fictitious with real characters. The novelist seems to be writing history and vice versa. This may help to account for his great popular success: he supplies neither footnotes nor index to distract that important customer, the common reader. After the highly controversial Keys of St. Peter, followed by his erudite tome on The Knights of Malta, M. Peyrefitte produced an elaborate period piece with the island of Capri as its background and foreground, for he was naturally drawn to this picturesque outpost of Hellenism. The period, often misnamed la belle époque, is the two decades preceding the first World War, and M. Peyrefitte has chosen to concentrate on its seamier side, its domestic scandals, perversities, frivolities, and florid bad taste.

The Exile of Capri is a romanticized biography of Jacques d’Adelsward-Fersen, poetically described by Jean Cocteau as “an Icarus whose wings melt in the sun of vainglory”—a poor little rich boy with whom it is hard to sympathize in spite of his inherent pathos. One regrets that a writer of Peyrefitte’s caliber should have wasted so much powder and shot on this third-rate exhibitionist, yet one cannot fail to admire his skill in marshaling relevant anecdotes, his architectural sense, and ability to administer and excavate so many buried facts. His aim was to satirize the flamboyant decadence of his hero’s environment, yet for once his satire is gentle, suffused with an undercurrent of nostalgia which gives the book an elegiac tinge. Compassion replaces Swift’s savage indignation, for Peyrefitte has a humanist’s kind heart. Hence the satire is not wholly successful.

Advertisement

In his autobiographical excursion, Looking Back, Norman Douglas remarked that Compton Mackenzie had caught the comic side of Fersen’s personality in Vestal Fire, but there was a tragic side as well. M. Peyrefitte had portrayed both aspects in this chronicle of a Capri long extinct—the sybaritic “Nepenthe” of Norman Douglas’s South Wind. Fersen, who might have been a good actor in another walk of life like his contemporary De Max, craved notoriety at any cost and was consumed with self-pity as soon as he achieved it—by giving absurd tea parties for schoolboys “to glorify the pagan religion.” Trouble with the police in consequence impelled him to settle in Capri, where he could indulge his taste for ephebes with less danger of interference. Even there his Neronian love of ostentation got him into hot water, for he was an irrepressible Captain Grimes under his thin veneer of greenery-yallery aestheticism. But his favorite color was pink, an attentive reader might object. Be that as it may, the effect was greenery-yallery. M. Peyrefitte describes his apartment in Paris as follows:

Jacques had put in electric light, a novelty at the time, and had daffodils painted on the milky glass lampshades. His big central room, its walls hung with Liberty silk, had been furnished with Louis Quinze day-beds, Turkish divans, Chinese pedestal tables, and Persian carpets. A piano and a harp confronted each other across it. A painting attributed to Boucher depicted “Venus among her nymphs.” There was a bronze group entitled, “Two Loves striving for a heart fallen at their feet.” A nielloed frame contained a photograph of Sarah Bernhardt swaggering as l’Aiglon. Two columns bore figures, one of Apollo, the other of Minerva. The bedroom was decorated with licentious prints and chasubles. The bathroom tiles and furniture were decorated with nosegays of roses, [etc.]

A lush and lurid conglomeration to dazzle his juvenile guests. Those milky glass lampshades adorned with daffa-downdillies might still make a few mouths water, since art nouveau is returning to fashionable favor. The Exile of Capri is a literary counterpart of the products of Gallé and Lalique.

Incapable of self-criticism, Fersen scribbled insipid verses and sentimental novels with such titles as Lord Lyllian, of which Norman Douglas remarked that it had “a musty, Dorian-Grayish flavor.” Jean Lorrain, whom he seems to have taken as a literary model, saw nothing in him but “the hypertrophy of an insufficient ego.” When he realized his failure as an artist he took to drugs. Perhaps opium helped to illude him that he was a creative genius: from opium he went to cocaine. The genial Norman Douglas, who discerned “some lovable streaks in him, some touches of genuine sensibility,” tried to give him some sound advice but he realized that the case was hopeless. Whereas opium could stimulate certain writers, including Cocteau, who contributed an eloquent Foreword to The Exile of Capri, it appears to have intensified Fersen’s mythomania: his pink roses turned blood-red in the Capri sunset.

Though Peyrefitte has delved with Teutonic patience and thoroughness into the sordid scandals of the characters who flit through his pages, The Exile of Capri is far from scandalous. It might even be described as a well documented sermon on the penalties of sexual aberration. As M. Cocteau, de l’Academie Française, exhorts us in his Foreword: “May The Exile of Capri serve to teach youth that beauty exists only if an inner beauty and hard work strive against and exorcize its arrogance!” And one is tempted to add: “Lilies that fester, smell far worse than weeds.” Certainly Peyrefitte has squeezed Capri like a sponge. The hordes of more or less standardized tourists who throng that island today offer meager grist to any potential rival’s mill.

Peyrefitte’s more recent book, The Prince’s Person, is scandalous indeed. Only those familiar with the original documents printed privately in Florence (II Glornale di Erudizione, 3 vols. 1886, I vol. 1893, with a preface by Giuseppe Conti) will be able to appreciate fully the comic art with which M. Peyrefitte has retold this historical anecdote, hinging on the sexual potency of Don Vincenzo Gonzaga, Prince of Mantua, after the non-consummation of his marriage to the Duke of Parma’s grand-daughter, who was very reluctantly relegated to a convent. Though for reasons of state Don Vincenzo appeared to be an eligible bridegroom, the Medicean Grand Duke Francesco I required positive proof of his virility before entrusting his daughter Eleonora to his conjugal embraces. The Farnese had spread a rumor that Don Vincenzo was to blame for the failure of his first marriage and the diplomatic démarches between prelates and princes, including a future saint, to investigate the truth, followed by the sacrifice of an innocent virgin who was used as a guinea-pig in the experiment, are related with ironical gusto by M. Peyrefitte in The Prince’s Person, of which Peter Fryer has produced an excellent translation. Don Vincenzo vindicated his sexual prowess under circumstances where many another prince equally potent might have failed through modesty. But the Renaissance, early and late, had little modesty, and publicity flourished long before the proliferation of the Press.

Advertisement

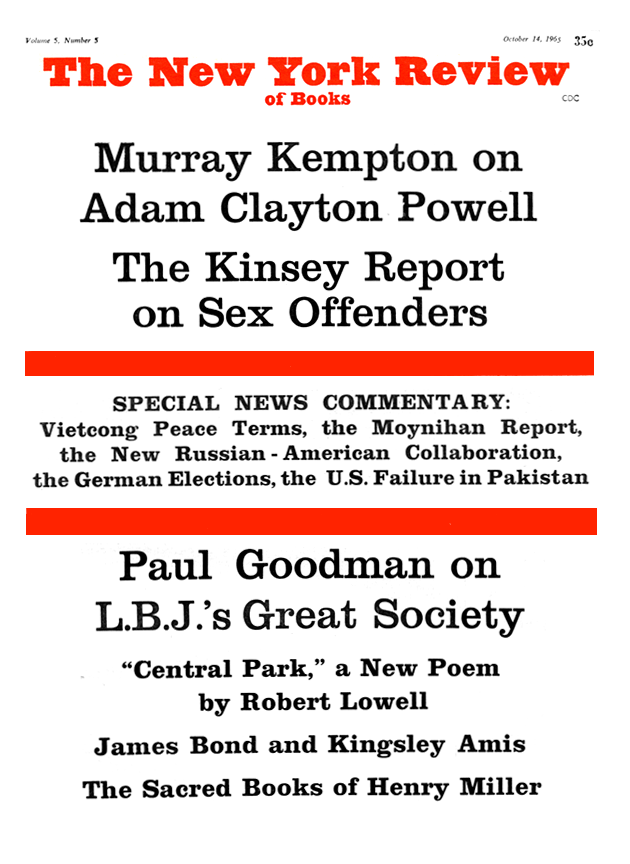

This Issue

October 14, 1965