The Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior is a book which should have been reviewed in my country by Professor Niko Tinbergen of Oxford University. It is just up his street. But since it has fallen to the writer of this review to do so, he would preface his remarks by one made by Colonel Meinertzhagen in the Introduction to his Birds of Arabia: “In case a reviewer troubles to read this introduction, let him first ask himself the question: Do I know more about this subject than the author? To be critical is easy; to be correct, not quite so easy.” There are few men with sufficient knowledge of live waterfowl combined with taxonomic and biological experience to review Professor Johnsgard’s book as it undoubtedly merits, and the present reviewer is not one of them! He can therefore only call attention to what strikes him as being an outstanding contribution to the study of animal behavior.

One of the chief aims which Professor Johnsgard set himself was to test the value and limitations of behavior—particularly sexual behavior—as an aid to classification. For this purpose he has “wandered about the Americas, Europe, and Australia” studying wildfowl in their native haunts and paying a visit of no less than twenty months to the Wildfowl Trust in Gloucestershire, England, where Peter Scott has the largest collection of living waterfowl in the world. Thus he was able to study at close quarters and to film an enormous number to which such access would have been impossible in the wild. From the 7,000 feet of film exposed there and elsewhere the drawings which embellish the text of this book were made, illustrating the courtship and threat displays and the many other postures employed by the duck tribe in their sexual behavior. As the author tells us, many species were studied in the wild as well as in captivity but in no case was it noted that the sexual behavior of wild and captive waterfowl differs significantly.

Professor Johnsgard then discusses in turn the general and the sexual behavior of the individual species in the three sub-families into which the Anatidae are divided (pp. 14-337), followed by a short summary of his conclusions. This section, in which he compares the behavior of the various “tribes”—a word coined by Jean Delacour, if memory serves—with one another, always with emphasis on their sexual behavior, is the most interesting in the book. In the Stiff-Tailed Ducks, for instance, at least two of the members have a major courtship display which consists of the male repeatedly drumming his bill on an inflated tracheal air sac!

The book ends with a classification table of the Anatidae based very largely on that proposed by Delacour and Mayr (1945) with subsequent revision by the first-named, but revised by Professor Johnsgard himself in the light of his own researches. In the course of his work he gives repeated acknowledgment to such well-known students of behavior as Heinroth, Lorenz, and McKinney, to the anatomical researches of G.E. Woolfenden and Verheyen, and to the suggestions of Dr. von Boetticher. Finally the author pays a warm tribute to Peter Scott, the Director of the Wildfowl Trust.

There is no doubt that Professor Johnsgard’s work will be widely acclaimed as a fine achievement. In the course of his study no less than 133 of the 142 extant species of Anatidae came under the author’s personal observation and only three of the genera, which the author accepts, were not personally studied—a statement which speaks for itself of the thoroughness of Professor Johnsgard’s investigations and the value which must be attached to his work.

The book is printed in clear type and has the great merit of being light to handle, the line illustrations being well reproduced on the non-coated paper. There are also some photographs, a particularly pleasing one showing a female Spotted Whistling Duck defending its brood.

The book is sure to find a prominent place on the shelves at Slimbridge and should be in the library of everyone with an interest in keeping waterfowl. Taxonomists in our great museums cannot afford to ignore it.

THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY is fortunate indeed to be able to call upon such rich talent as is represented by the contributors to this volume, for in addition to Dr. Wetmore, whose name is a household word in whatever country ornithologists are gathered together, there are chapters in the book from the pens of John W. Aldrich, Dean Amadon, Philip S. Humphrey, Robert M. McClung, Alden H. Miller, Robert Cushman Murphy, Roger Tory Peterson, Olin Sewall Pettingill, Jr., Austin L. Rand, S. Dillon Ripley, and George Miksch Sutton among others. The book is a companion volume to Song and Garden Birds of North America, published by the Society in 1964.

Advertisement

The names listed above are a sufficient guarantee that the volume contains accurate and often unusual information. We are told on the title page that 329 species are portrayed in color and are fully described. What is meant by “fully” is generally a short paragraph to accompany the colored illustration in which the chief characteristics of each bird are noted and two or three lines of plumage description, the rest of the paragraph occupied by field notes and general range. It is noted that despite the title of the book, any bird which has remotely occurred on the fringe of the area, such as the redbilled tropic bird Andean Condor, and some almost entirely tropical Petrels and Albatrosses, has managed to find a niche in the book, without, it seems, very much reason, unless it be to give so distinguished a naturalist and writer as Dr. Robert Cushman Murphy an opportunity to write widely on the topic with which his name will forever be associated.

Of the vast number of illustrations with which this volume is crammed, many are from color photography at its best, but however good the photographs may be, this reviewer, being perhaps old-fashioned, will always give pride of place to reproductions from the work of first-rate bird artists of which America has produced such outstanding examples.

As we should expect of the National Geographic Society, the book contains some striking scenic pictures, such as that illustrating the haunts of the Phalaropes (pp. 348-9) and of the guano birds off the Peruvian islands (pp. 84-5 and 70-71), and of Lake Tule, California (p. 190), whereas the picture (on pp. 134-5) of some tame Flamingoes backed by a crowd of admiring tourists came as a distinctly jarring note in a volume under such distinguished authorship. Surely entirely out of place in even a pseudo-scientific work. Nor does this reviewer appreciate the habit of printing an entire page in glaring color (see pp. 48-49, 208-9, and 384) more suited to a fashion magazine than scientific literature in however popular language it is couched. Most of the writing is first-class and it seems a pity to cheapen a good book with such flights of “artistic” fancy.

Apart from such matters of opinion, which may not be shared by the American public, for whom, after all, the book is intended, Water, Prey and Game Birds is a fine production with a great wealth of informative matter under one cover. It is sure to meet with tremendous success. With the volume six long-playing vinyl records of bird song are presented, clearly explained by Dr. Paul Kellogg in the holder. The voices of 97 different birds have been captured.

IN JEAN DELACOUR’S The Waterfowl of the World (Vol I, 1954) that author wrote, p. 163, “the Giant Canada Goose appears to be extinct.” It was named by Delacour himself Branta canadensis maxima in 1951 from a specimen from Minnesota in the American Museum, and was then believed to be non-migrating, breeding in the great plains of the Central United States. Among its characteristics it was said to weigh “up to 18 lbs.”

Canada Geese have a huge distribution in the Nearctic Region and extend into Asia. Delacour accepted no fewer than twelve subspecies, including maxima and how this large race came to be written off as extinct this is not the place to argue.

In The Giant Canada Goose, Mr. Harold Hanson first of all sets out to document the history of the efforts made to gain recognition of this race, observing that it is a story from which professional biologists and conservationists can take little satisfaction. Branta canadensis is, as we all know, a very puzzling species. The many scattered populations live, while on their breeding grounds, in isolation; but after migration (which is normal) they are often mixed up in the same wintering area with other races, though apparently even then, the flocks of the different subspecies keep to themselves. Parents and young stay together for nearly a year. The races are distinguished from each other mainly by size, but in the Canada Goose there is considerable variation in color shade as well as size. No species of goose has been more studied by taxonomists, who are, as usual, prone to disagree in their conclusions. In this case they have some excuse.

It is safe to say that Mr. Hanson—even before the publication of this book—has done more than anyone (in conjunction with R. H. Smith: Canada Geese of the Mississippi Flyway) to elucidate the many problems which the Canada Goose presents, and in this closely documented volume under review, illustrated with many fine photographs, he gives us a treatise on the Giant Canada Goose in such detail, discussing every aspect of the bird’s life and physiology, as to leave this reviewer amazed that so much information can be gathered on a single subspecies. Whether this giant member of the species occurring in widely separated areas truly qualifies for subspecific rank must be left to the experts to decide. It would appear to be what Professor Ernst Mayr terms a “polytopic subspecies.” Of its extensive but scattered breeding range as accepted by Mr. Hanson, and its winter distribution, full details will be found in this book. These very large geese, with massive bills, are partially migratory, those populations nesting in the northern sectors of the Great Plains of the United States and those breeding in the prairie provinces of Canada being forced to migrate because of climatic conditions. Many flocks, however, tend to be non-migratory, if food and some open water are available. In the weight-table (pp. 16-17) Canada Geese are reputed to have turned the scale “at over 16 lbs.” The maximum variation is said to reach 24 lbs. (!), although evidence for the highest figure seems unsatisfactory.

Advertisement

Mr. Hanson’s conclusions will no doubt be subjected to close scrutiny by those who have made geese their special study, and reviews of his book in the scientific journals will make interesting reading. Should Delacour’s maxima for any reason not be applicable to the “new” Giant Canada Goose, it should certainly be named in honor of the late W.B. Mershon, who for seventeen years tried to have the race recognized.

For a piece of fine research Harold Hanson is to be warmly congratulated. If the author is anything like the attractive photograph on the dust-cover, he is also a fine sportsman, well worthy of bagging a “Giant Canada” weighing at least twenty lbs.

IN A CONVENIENTLY handled book, Philip Brown presents short informative essays on those birds of prey, diurnal and nocturnal, which normally breed in the British Isles, and which, as a former Secretary of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, he did so much to conserve. Birds of Prey is called “A Survival Book” (Editor Colin Willock) and in its pages the author tells of the struggle that birds belonging to the families of Hawks and Owls are having to escape extermination—this time not directly at the hands of man by shooting and trapping and egg-stealing, but by the much more dangerous and deadly agency of toxic poisons, chemical sprays, and such like horrors which have already, we trust unintentionally, but certainly callously, taken such a toll of bird-life. America is no more free of the menace than we are in Britain. Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring did much to bring the state of affairs before the American public and if Philip Brown’s account of British birds of prey contributes to the same end (as I am sure it will), it will be well worth reprinting in every language under the sun where chlorinated hydrocarbons are sowing death and misery among thousands of birds. Governments are unfortunately slow to act, even when, at long last, they are persuaded that irrevocable harm is being done. Public opinion is perhaps the strongest card which nature lovers have to play in their efforts to save the birds. Perusal of Philip Brown’s essays will help to convince the public what we shall have lost if the Eagles, Buzzards, Kites, Falcons, Harriers, and Owls are swept from the skies and woods and sea-cliffs where they give infinite pleasure to so many and do so much good and so little harm.

The excellent photographs would have been so much better placed with the appropriate text instead of all being bunched together between pages 56 and 57. Surely an unnecessary economy?

Although there is little new in what Mr. Brown has to say, his chapters are pleasantly written and should stimulate an interest in the birds discussed in his pages.

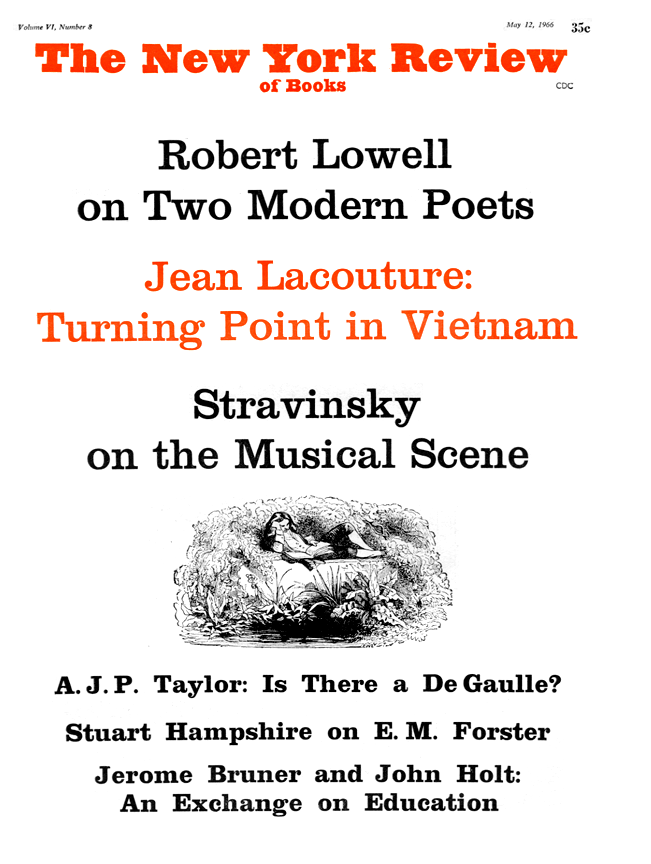

This Issue

May 12, 1966