In response to:

The Little Foxes Revived from the December 21, 1967 issue

To the Editors:

Even those who believe that Francis Bacon wrote the plays attributed to Shakespeare will not believe that Lillian Hellman wrote the plays attributed to her by Elizabeth Hardwick [NYR, Dec. 21, 1967]. To begin with an elementary point, no one who for whatever reason dislikes The Little Foxes or who for good reason objects to the casting, in the Lincoln Center Production, of Pearl Bailey as Regina will recognize that suitcase Miss Hardwick “seems to remember” in the last scene. There isn’t one. More importantly, no one who knows the play can make the misreading necessary to Miss Hardwick’s political interpretation of it: that Birdie “represents culture.” Even through the Cockney “Oscars” of Margaret Leighton, one could hear what Hellman wants us to hear—Birdie’s besotted, pitiable, aggravating frailties of pretension that justify the irascibility of her husband as well as his weakness in relation to the other Hubbards. But Miss Hardwick doesn’t want to think that the characters exist in relation to one another. For her they are so many inadequate historical imitations, mismanaged in a hopeless dissertation on Southern Agrarianism submitted by Hellman every now and then to Vanderbilt University.

It really doesn’t matter that Miss Hardwick, expecting W. J. Cash’s history of the past in Hellman’s play, is angry not to find it there, any more than it mattered awhile back that in a novel she disliked she could not find “evil” that was “instructive.” Plucked from some child’s toyland of neo-classicism, the standards of history and probability, or representativeness and instruction have appeared in quite a few of NYR’s keynoting reviews of fiction and drama. What’s disconcerting in Miss Hardwick’s review of Hellman is the way these standards are put into play with a late nineteenth-century ogre named “melodrama.” Miss Hardwick’s notion of “melodrama” might at least have saved her from wondering why Horace doesn’t respond to the history in Cash’s Mind of the South, rather than to the dramatic possibilities of repentance in a household like Regina’s, and it might have kept her, too, from complaining that the German refugees in Watch on the Rhine did not go to Fort Washington Avenue instead of to a country house near Washington D.C. where, freed of commuting, they could spend more time in the kind of environment to which Hellman wanted to expose them.

When Miss Hardwick’s next successor for the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism is selected, maybe the judges should test the candidates with a question once asked by a teacher of mine at Amherst—“why did Friar Lawrence leave the tomb?” We were freshmen, and after we tried Miss Hardwick’s sort of thing, including attacks on the scene’s improbability, the answer turned out to be a memorable hint about what a play, melodrama or not, has a right to be and what it has a right not to be—“because,” said the teacher, “Shakespeare wanted it that way.” A simple lesson maybe, but it’s at least a protection from the confusion that because the theater may be political, politics is therefore the theater.

Richard Poirier

Rutgers University

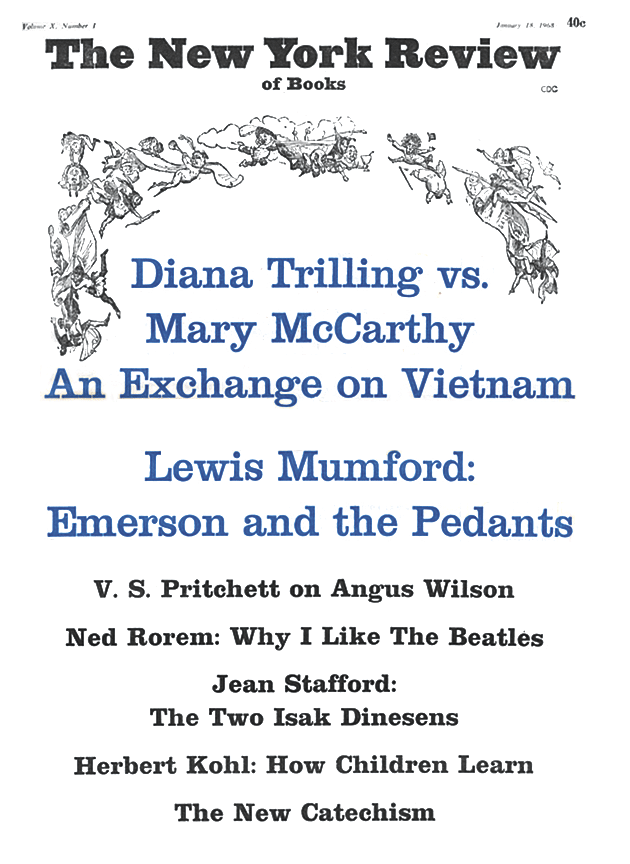

This Issue

January 18, 1968