The Age of Reason followed by the Age of Science wrecked the traditional presentation of Christianity. That they failed to wreck historical Roman Catholicism until our own time was largely owing to the authoritarian nature of that Church. From the intellectual point of view, Roman Catholics lived in a game reserve which, as outside pressures mounted, gradually contracted into a zoo. Reluctantly, the Second Vatican Council unloosed the rusty bolts. Most of the animals remained bewildered and shivering behind the bars. A minority dashed out and scattered in all directions.

The first of this group to organize themselves were the Catholics in the Netherlands. For the past five years the faithful have been scandalized, delighted, shocked, stimulated, and outraged by reports of the goings on in Holland. Dutch Catholics, it is said, with the connivance of their Hierarchy, have denied Transubstantiation, defied the Roman Curia, cocked a snook at the Pope, declared contraception a matter for personal choice, homosexuality no longer a mortal sin, intercourse before marriage a good idea, held joint services with Protestants, celebrated something suspiciously like a New Testament agape, announced enforced clerical celibacy to be against the Natural Law, and co-opted Calvinists into their National Council of Bishops. Cardinal Alfrink, the Archbishop of Utrecht, has had to defend his province against a charge of disloyalty, papal encyclicals reproving those pastors suffering from “the virus of rationalism” who are “disturbing the faithful and filling their minds with no little confusion” have been plainly directed to the mouth of the Rhine. The white hope of the Catholic liberals, the Dutch friar Fr. Schille-beeckx, accused of expressing heretical opinions during an international theological conference at Toronto, established his orthodoxy only by producing tape recordings after an uncomfortable lunch at the Hotel Columbus with three Consultors of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith.

SOME OF THESE reports are, of course exaggerated and taken out of context. But the anxiety both of the Pope and the Curial party at Rome is evident. So is the fact that the Dutch Church is in a state of ferment and revolt not only against accepted structures, but the traditional formulation of Catholic doctrine. There is fear, in more conservative quarters, that the contagion may spread. In the United States, to some extent, it has already. A popular English Catholic weekly promised a series of articles under some such intriguing title as “What really is happening in Holland?” Those who bought the paper at the church door next Sunday hoping to hear that the Dutch were chopping up their confessional boxes for firewood had a disappointment. The editor, it seemed, had decided after all not to let the faithful know what was going on in another part of the Universal Church.

It is against this background that the farcical row over the publication of A New Catechism must be set. Like all ecclesiastical squabbles its development is complicated, not altogether clear in detail, funny, and sad. Funny, because it is one of life’s blessings that all clerical maneuvers take on this quality. Sad, because behind the evasions, contradictions, and strategic withdrawals, lies a sincere and fundamental split; and because upon its closing the faith of so many depends.

TO MOST PEOPLE who have had a Christian education, whether Protestant or Catholic, the word “catechism” means a small book provided for the instruction of children, which contains questions and answers to be learned by heart. The Dutch Catechism is nothing of the kind. It is a large volume of some 500 pages and, far from being suitable for children, is intended for adults of university education and background. It contains, in the accepted form, no questions, and, as its detractors would say, no answers either. Its object is to write an exposition of the Catholic faith in terms such an audience can understand. It has been widely acclaimed. “…a magnificent attempt to state, comprehensively and persuasively, the full account of the inner meaning of the faith.” “A priest should feel quite happy to put it in the hands of sixth-formers, or those under instruction, or those wishing to deepen their understanding: it is a most valuable compendium of Catholic belief and practice in contemporary idiom.” These opinions from two prominent Jesuits show which readers the book has been designed for, but they have, too, an ironical significance in view of the extraordinary events that followed its publication.

First of all it should be clearly understood that the Catechism is not the work of an isolated theologian or independent group of scholars. It was commissioned by the Hierarchy of the Netherlands and produced by the Higher Catechetical Institute at Nijmegen. The Dutch edition bears the imprimatur, or license to print, of Cardinal Alfrink and a Preface written in the name of the entire bench of bishops. When it was first launched in the autumn of 1966, the Cardinal said at the press conference: “They [the bishops of the Netherlands] have accepted this book and they offer it in virtue of their office and charge to all who, in our day, want to hear what the Church has to say. They do this, certainly, with the authority which belongs to their office as the first among the teachers of the faith. The new Catechism is not intended to be a completely unguaranteed text to be questioned at will.” This was optimistic indeed. A month later a group of conservative Dutch Catholics appealed to Caesar. They represented to the Pope that the Catechism deviated so far from traditional teaching that it amounted to heresy. No one knows for certain what these heresies, or quasi-heresies, or imprudences are. Some say they number seven. Others forty-eight. As for their nature, Adam and Eve, Original Sin, the Virgin Conception, and birth control seem to be the most likely subjects.

Advertisement

Translators were busy. The English language version was completed early in 1967, and in the summer Bishop Joyee of Burlington, Vermont, granted it his imprimatur. Then Rome spoke. It was announced that a doctrinal commission had been set up to study the Catechism. The Dutch Hierarchy agreed not to authorize further translations of the work they themselves had guaranteed. Cardinal Alfrink sent to the Curia rewritten passages on contested points together with extensive alterations. The unfortunate Bishop Joyce “out of loyalty to the Holy See” hastily withdrew his imprimatur. It was therefore removed from the American edition. Since the British edition was printed before Bishop Joyce’s withdrawal however, we have an odd situation. The American edition bears the imprimatur of a Dutch archbishop, the British that of an American. The dust jacket of the former declares the book to be the “authorised edition of the Dutch Catechism.” The jacket of the latter carries the more modest description “the famous Dutch Catechism.” The contents are identical.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the Catholic bishops meeting in Washington have refused to recommend (pace those Jesuits) the adoption of the Catechism as a text for the teaching of religion, “because the book is being presented to the American public as an authorized edition although it does not in fact have such approval.” Cardinal Alfrink has been quoted by the Vatican daily L’Osservatore Romano as “regretting” the English translation. Regretting the dissemination of a book which was offered in virtue of the episcopal teaching office and addressed to all those who want to hear what the Church has to say? The regret, if it exists, cannot be very deep. For the Dutch Hierarchy have not withdrawn their authorization from the original edition, and what is sound doctrine for the Catholics of the Netherlands can hardly make dangerous reading for the rest of Christendom. It is said that three-quarters of a million copies have been sold in Holland, and the American publishers have started a second printing of 50,000 further copies of the unchanged version. They intend to incorporate all suggested alterations into future editions. They add, further, that in fact the commission of theologians has already completed its task and has recommended only a “few very minor changes.” It seems, however, that the Cardinals in charge of the theologians have not yet acted on their advice. The position, therefore, at the time of writing, is as uncertain as ever.

The moral of all this is plain. Those who want “to hear what the Church has to say” will have to wait until the Church knows herself. That cannot happen in our lifetime. But it would be a very great mistake to allow the value of this Catechism to be obscured either on account of distaste for the notoriety which has surrounded its publication or because it can only be an interim report.

The opening paragraph sets the tone for the book and shows the reader how utterly different the whole approach is from customary Roman Catholic treatment of this subject. It starts with that passage from Bede where the historian, describing the mission of St. Paulinus to convert King Edwin to Christianity, tells us how one of the King’s advisers compared the life of man to a small bird flying from the Northumbrian dark for a short space into the warmth and light of the hall, then out again once more into the winter night. We used to be told that this was a typical example of Anglo-Saxon melancholy. We now call it the human condition. It is, then, from the human condition, not revealed doctrines about God, that the compilers of this Catechism start. Instead of the old treatment which consisted of water-tight sections entitled “The Church,” “the Sacraments,” the Ten Commandments,” and so on (and, I fear, so forth) topics are subtly woven together to form an intelligible whole, strengthened throughout by an apt selection of much biblical, liturgical, and historical material. The intention is to lead the reader from man to God via himself, comparative religion, the Old and New Testaments, the history of the Church, the interior life of faith, and its external expression exemplified by Christian conduct.

Advertisement

THE APPROACH is admirable. So is the writing. The general manner is quite free from the old take-it-or-leave-it, spiritual recruiting-sergeant attitude which characterized old-fashioned apologetics. But what of the actual content? After all, the point of Bede’s narrative does not lie in a striking literary image. “We do not know,” it continues, “what went before and we do not know what follows. If the new doctrine can speak to us surely of these things it is well for us to follow it.” How surely does this Catechism speak?

To answer this question justly is to indicate the fundamental weakness of the Catechism At its heart lies not a spiritual but an intellectual ambiguity. It could not be otherwise. This ambiguity is of two kinds. The first is a direct consequence of that uncertainty, shared by all Christians, about what exactly they believe and their grounds for doing so. The second, nowadays, is more or less peculiar to Roman Catholics. Archbishops, even Dutch archbishops, do not want an out-and-out breach with the central authority. Openly to defy the Pope could only mean a futile schism. Catholicism, to use the expression the authors here employ to describe a feature of Hinduism, has “surpassed its own principles.” Its truths can be spiritually illuminated and made rationally acceptable only by repudiating a good deal of the letter of its former teaching. Liberal Roman Catholics, therefore, find themselves in an awkward, not to say paradoxical, position. They have to work within existing structures. Yet what they are working for must ultimately destroy those structures. As for those who say that, under such circumstances, bishops have no business to start writing catechisms, let them consider the world as it is, not as they would like it to be. St. Paulinus’s task was simplicity itself compared with Archbishop Alfrink’s. If this Catechism had pretended to know all the answers it would have been a fraud. If it had made the logical consequences of some of its views more explicit, it would have collided head on with the Roman authorities, alienated the mass of the faithful, and failed to get a hearing at all.

Rome is said to have exhibited no little uneasiness on the subject of “Man’s First Disobedience and the Fruit of that Forbidd’n Tree.” This is a good example of the difficulties that best the authors. As historical figures Adam and Eve get their quietus. The notion of an earthly paradise is scouted. The whole problem is treated with a penetration which takes into account scientific findings together with religious and moral values. It is a great improvement on the ancient improbabilities that did so much to widen the gap between the teaching of theologians and the belief of educated people. Contrary to rumor, Original Sin is not denied. But it no longer means what it used to mean. The Catechism takes the now common view that it is less of a sin than a propensity to evil which takes on concrete form in our personal sins. This interpretation raises as many questions as it answers, but perhaps it is about as far as we can get. One conclusion, though, is inescapable. Since, as the authors put it, no one is lost except for the sins he has personally committed, Limbo and the necessity of baptism for the salvation of infants fly out of the window in company with the relevant decrees of Florence and Trent. If decrees of General Councils are to be set aside when they conflict with knowledge and moral attitudes which their participants could not possibly have possessed, well and good. But it is confusing, in the same book, to read about the infallibility of General Councils without a more realistic and factual discussion of how that infallibility is expressed.

“The day,” George Sand announced, “the Church of Rome made damnation eternal she consummated her suicide.” The Catechism understands what it calls, in an oddly discordant way, “reprobation” to be the self-inflicted pain of the conscious loss of God endured eternally. To their credit, the authors do not try to shuffle out of this notorious difficulty by glossing over the evidence of Scripture and the Church. Less to their credit, they do not seem to perceive that although, as they put it, “we must not manufacture for ourselves a God of our own” it remains true that we cannot think of God as being less good than our fellow men. They pass over in silence the Church’s doctrine that the damned suffer pain of sense. What they have to say about the nature of sin and the extent of personal responsibility is excellent. A pity they did not go further and suggest a solution which would at the same time safeguard these truths and not violate the human conscience.

ON A LESS important matter the same conflict between head and heart is apparent. It is not true that the Catechism “allows divorce,” or undermines the sanctity of marriage, or any other rubbish that has been put about. It insists strongly on the indissolubility of a consummated Christian marriage. However, when it comes to “hard cases” it admits that it is not given to us infallibly to know “who is really married in Christ and who is not.” Quite so. But the trouble is that the Roman Catholic Church has always claimed, on the contrary, that it is given to her to know. What of those thousands of Catholics who, at this moment, are being deprived of the sacraments and denied the practice of their religion precisely because the Church has told them they are living in sin?

The treatment of the Virgin Conception—the doctrine that Jesus had not a human father—in many respects so illuminating, contains a puzzling feature. As the Catechism stresses, Christianity stands or falls by the truth of certain allegedly historical facts which, although they transcend it, belong to the order of empirical experience. Either Jesus performed certain actions we call miracles, or he did not. Either his bones are mingled with the dust of palestine, or they are not. Facts of this nature are in principle subject to historical verification, but they have long since eluded our grasp. Christians believed that the Gospels were true, not because they could be empirically proved, but on the word of the Church which complied them. Despite the authors’ conservatism about New Testament miracles in general, they draw back when it comes to the Virgin Conception. They neither deny its factual truth nor do they assert it. Some Christian teaching must be understood in the spirit and not the letter. But the Virgin Conception is dependent on its literal meaning. Either Jesus was conceived in the normal biological manner or he was not. If he was then the Church has been teaching substantial error for nearly 2000 years and what value can be placed on her word? The question here is not whether the orthodox doctrine is actually true, or whether its acceptance is essential to the Christian faith. No doubt the traditional affirmation will be inserted into the revised edition. What is perplexing is the Catechism’s apparent blindness to the radical implications of its own deliberate hesitation.

Compared, however, with much Christian speculation, the Catechism is on the whole conservative. This is shown, for example, in its treatment of the Divinity of Christ, the Apostolic Succession, and Holy Orders. The general approach to the thorny question of the historicity of Scripture is, as one would expect from such distinguished theologians, up-to-date and moderate. As for contraception, the liberal view is adopted. Without repudiating the values the Church’s prohibition was intended to protect, that prohibition itself is rejected. The number of children is no longer to be left to “the blind forces of fertility” but to the individual conscience in consultation with a doctor of medicine. Abortion, on the other hand, is condemned without any real effort to go into the complexities of the matter. Homosexuality is treated with a sympathy and compassion undreamed of a few years ago; whether it is a sin is not altogether clear.

In the last analysis, this Catechism is neither Catholic nor Protestant. It is a tentative, necessarily unrealized, stretching out toward a Christianity which, we hope, one day will combine the best in both traditions. As an attempt to put new wine into old bottles it is unconvincing. But as a powerful witness to the validity of the spiritual experience which runs beneath the surface of our present troubles, it is an assured and impressive achievement.

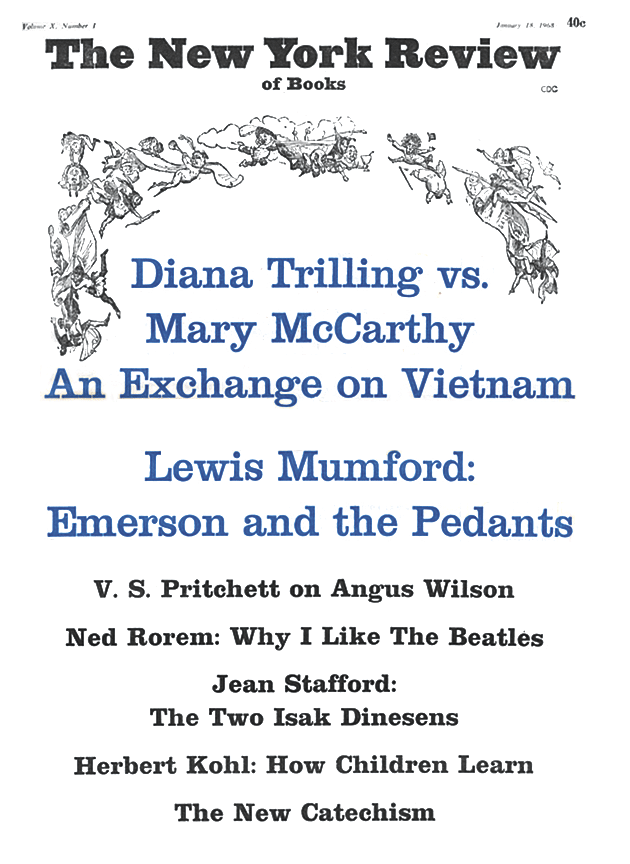

This Issue

January 18, 1968