There are those survivors of political disaster whose experience is like that of a man trapped in the air-raid cellar of a bombed house: an eyeless, troglodyte’s underworld to which, none the less, there faintly penetrate the sounds of the daylight street above, following its normal middle-earth concerns. Such is the experience of Jiri Mucha, who survived the coal mines and uranium mines of Czechoslovakia under Stalin. And there are those who have survived the nuclear explosion itself, the total holocaust, so that there no longer exists a world to return to: here is the place of Elie Wiesel, revisiting the metaphysical crater where once there existed European Jewry. Lastly, there are those whom the blast scorches and bruises but leaves still upright, still with the breath to yell back in fury and outrage. This is the category of Vassilis Vassilikos, the young Greek novelist and left-winger who watched the rise of fascism in Greece before the coup of the Colonels and must now live abroad.

Book after book which emerges from Czechoslovakia uncovers a little further the sheer size of the wound which the political trials conducted by the Communists made in the public consciousness. The seven months of liberty, and the twilight of literary tolerance that preceded them, have produced accounts of the Slansky trials alone which amount to a small library of nightmare—the accounts of Mme. Clementis, of Slansky’s widow, of Mme. Slingova, of Eugen Loebl, to name only some of them—but they have shown, too, how much still remains to be revealed. As an account, not of his trial, but of the life of the prisoner, Jiri Mucha’s book surpasses them all. Condemned in 1951 for “spying for the Americans” to six years’ imprisonment, of which he served three, Mucha was the novelist son of the great “Jugendstyl” painter Alfons Mucha. He entered captivity as a young Western intellectual whose roots were in the Czech lands but who had lived in Paris and New York, traveled in the Middle East, and served most of the war in Britain with the Royal Air Force. Living and Partly Living (the title is a quotation from Murder in the Cathedral) is the diary and commonplace book which Mucha kept during the year he worked as a penal laborer in a coal mine.

Mucha’s job was to manhandle loaded coal-tubs round a turntable below ground. The paper on which he kept his journal was hidden under lumps of coal in a tin with a few pencil stubs, dug out and re-buried every day. Even when things were normal, he had constantly to drop his writing and attend to the coal-tubs rumbling down the gallery to him from the mine face. And in this death-hole of a pit, where the equipment was totally worn-out and men smoked freely below ground, explosions, roof-falls, and accidents were frequent. “Bergson maintains that—“ Mucha begins and then drops everything as he hears the thunder of a runaway tub hurtling down the drift toward him. Afterwards, it is hard to remember what Bergson did maintain. Yet in these conditions, listening with half an ear to the rustling and cracking of the coal around him and the faint stress-cries of pit props gradually bending under the strain, Mucha produced a small work of literature.

It is fragmentary, of course. There are descriptions of his life and his companions in the pit and the camp above ground: “…the beauty of the people is composed of a large number of small hideousnesses.” There are records of extraordinary moments: Stalin’s death, with the funeral music from Götterdämmerung blaring from loudspeakers in the cold night just before dawn, as the shift arrives at the pithead under the red neon star, the black smoke pouring upwards in the gale—this is put down with all the energetic visual detail of his father’s painting. There are long essays in criticism, snatches of dialogue between prisoners, reportages like his account of a journey through the Sudetenland as the Germans entered, and much humor. There are minute reconstructions of remembered scenes on the sunlit middle-earth above. There is a violent revulsion from Czech behavior under Occupation: “…petty-bourgeois mice. The people had become puny and grey and even their noses had grown long like mice…the return of that cowardly pettiness, just as a generation, born without imperial Austrian gendarmerie, was beginning to overcome it.”

Outside, a sort of life goes on. Mucha dreads his release: he must remain the same, while others outside grow and change. He watches the release of a German going reluctantly out into a world which has nothing for him, “only the backward view on his own life which had expired and a forward view to a lonely old age…his past was dead. He had nothing to return to.”

Advertisement

What had Elie Wiesel to return to, as a Jew from Transylvania who emerged living from the extermination camps of the “Endlösung” and now revisits Eastern Europe, even Germany? The author of three other books, he has produced in Legends of Our Time a series of brief imaginative confrontations with the past. Two pieces stand out, his visit to the town from which he was deported and the extraordinary short story, “The Wandering Jew”; but in all of them the confrontation becomes no confrontation. Nothing can be revisited, the dead cannot be resurrected, even the guilty have forgotten their guilt and the teachers—the source of order and authority and interpretation—have vanished. In “The Last Return,” Wiesel returns to Sighet, now in Rumania, and seeks what is to be found from the days before he and 10,000 other Jews were deported in 1944. The streets are there, his house is there, and yet—so it seems to him, wrapped in the invisible cloak of self-tormenting, almost guilt-ridden emotion which so many “heimkehrer” wear—the Jews have been utterly forgotten. In fact, the people of Sighet “give the impression of having nothing to forget. There never were any Jews in Sighet, the former capital of the celebrated region of Maramures. Thus the Jews have been driven not only out of the town but out of time as well.”

Wiesel also continues his search for hate, for his own ability to detest the enemies of his people. “Appointment with Hate” is about Germany, but hate fails to keep this appointment. The Germans he found polite, self-confident, distressed but not especially concerned about the past. Not without irony held well in check, Wiesel examines his own wildly veering reactions to this. “I was ashamed of having permitted my hate to get away from me. It was this shame which overcame me in Germany: I was betraying the dead. Instead of judging the Germans, then, I judged myself.” He asserts that “whoever does not hate when he should, does not deserve to love when he should,” but adds, with his own characteristic plaiting of thankfulness and resentment, that “two thousand years of persecution…had only immunized [the Jewish mentality] against hate.”

He carries this further in a brilliant little story called “An Old Acquaintance.” In a Tel Aviv bus, he suddenly recognizes in the man sitting opposite him a brutal “Kapo” from one of the Auschwitz “Aussenlager.” The narrator challenges the Kapo, who refuses to admit his identity. Choosing to play this on his own, and not to call for the police, the narrator (or perhaps Wiesel’s imagined self) resolves that “facing the accused, I will be God.” He will judge this man alone and force his confession. At the end of the line, at the darkness at the last bus-stop, the Kapo suddenly drops his steady denials, swings on his accuser, and screams threats at him in camp German. And what happens? “I am suddenly aware of my impotence, of my defeat. I know I am going to let him go free, but I will never know if I am doing this out of courage or cowardice…. But I will have acquired the certitude that the man who measures himself against the reality of evil always emerges beaten and humiliated.” He turns away from the yelling man, moves off in a walk which changes to a run. “Is he following me? He let me go. He granted me freedom.” This, like several other stories in this volume, is writing of the highest quality. It is also history: the final light of art upon that unbearable controversy about those who went unresisting to their death.

Z is a loving, almost fond, reconstitution in fiction of the murder of Lambrakis, the left-wing Greek leader and member of Parliament who was knocked down and killed by a motorcycle van in Salonika after addressing a pacifist meeting there in 1963. Vassilikos, we are told, “digested five thousand pages of testimony” and “keeps to the historical facts.” The reader is taken into the underworld of Salonika, among the fruit-sellers dependent on police licenses, the desperate who would, for money, even stand accessory to murder, the old collaborators from the Occupation who have poured their fascism into the vessel of royalism. Lambrakis, referred to as “Z,” emerges as a superhuman figure of hope and virtue. A long and rather unsuccessful rhapsody describes the journey of his coffin by special train from Salonika to Athens, his soul hovering above it like a regretful captive balloon. A very much more moving series of soliloquies is attributed to “Z” ‘s widow, as she attempts to come to terms with his death. “I imagine myself at a railway crossing and the guard has put up the chain between us, an endless train roars over the rails with as many cars as the years I shall not see you. Only at fleeting moments, through the spaces between the cars, I catch a rare image of you waiting for me on the far side.”

Advertisement

But the bulk of Z is the story of the judicial search for the guilty, the unraveling of one layer of official corruption and intrigue after another, the sudden “breaks” in the hunt as a fresh witness comes forward, the supple chain of old fascists and their agents which protected the commanders of the Salonika police. Vassilikos here identifies and analyzes precisely the fertile compost which was, almost at once, to produce the monstrous growth of Greece’s present dictatorship. It all moves and instructs, but the murder of Lambrakis seems too close and relevant to be suitable material for balladizing. Perhaps the libel laws play a part, for Vassilikos has hidden real names under the titles of prehistoric monsters which never existed (“Autocratosaur,” “Mastodontosaur”). But the book leaves one longing to read a straight documentary account of this prophetic scandal.

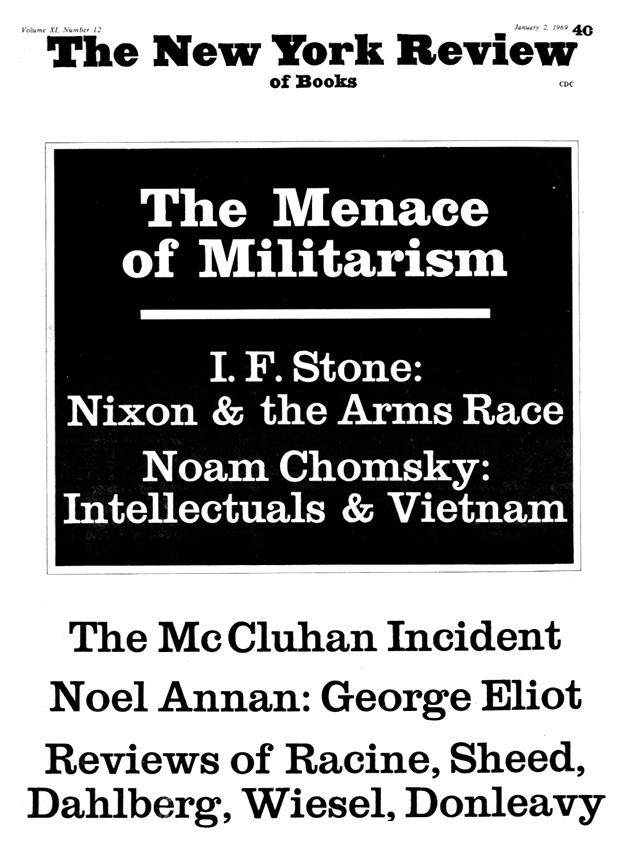

This Issue

January 2, 1969