In response to:

All in the Mind from the January 16, 1969 issue

To the Editors:

I hope you will permit me to correct an important error and point out an omission in Charles Rycroft’s interesting All in the Mind, a review of C.G. Jung’s Analytical Psychology: Its Theory and Practise. He reproduces what he calls two “diagrams of the mind,” one by Jung and one by Freud, which he thinks would be “almost identical” if Jung’s diagram “were rotated ninety degrees.” They are both “metaphorical artifacts” which are “unnecessary,” in Rycroft’s view, and do not do justice to the real nature of mental processes, which would be better represented in “auditory, musical language” than by trying to describe their spatial relations, which “derive as much from the facts of geometry as from those of psychology.”

What Rycroft fails to mention is the title of Jung’s diagram which is simply “The Ego,” and this is only the second in a series of four diagrams. This is the least important and limits itself to only one aspect of the ego. Freud’s, on the other hand, is a diagram of the intricate relationship between the Ego, the Id, the “repressed” and the Pcpt system, and is therefore a diagram of mental processes of a very far-reaching nature. It is unfair to both of these great pioneers to compare these two diagrams, and to imply that there is not much difference in their basic concepts. Later on, in this same volume, Jung produces a diagram which fully shows his much more complex conception of the psyche, and here I think we see how in this he did satisfy Rycroft’s wish that we should have a “psychology in which thoughts are conceived of as themes.…. which can undergo development and variation” (see p. 49), and also how totally different this is from anything Freud ever envisaged.

I should also like to say that, having been, myself, present at this series of lectures, I can testify to the fact that Jung was being very much himself and did not, as Rycroft states, artificially assume a personality which he thought would please the English. He was not playing a role when he appeared to be “a direct man, down-to-earth even when scaling the heights or plumbing the depths,” and a careful reading of the discussions shows how much his audience appreciated and responded humanly to this naturalness of expression.

Joseph L. Henderson, M.D.

President

C.G. Jung Institute of San Francisco

San Francisco, California

Charles Rycroft replies:

I think Dr. Henderson has mistaken both the tone and the intentions of my review. I was not seriously suggesting that there are no significant differences between Freudian and Jungian psychologies but was concerned to make three skeptical points: 1. The original formulations of psychodynamic theory were much more influenced by the personalities and styles of thinking of their creators than they themselves realized; 2. Both Freud and Jung got themselves into a position in which they were able to impose their own (possibly erroneous) views of themselves on their followers; 3. Writing as they did before the advent of techniques of linguistic and semantic analysis they were oblivious of some at least of the pitfalls surrounding the construction of psychological theories.

Dr. Henderson evidently takes more seriously than I do the possibility of constructing a psychological theory based on music. Perhaps I should refer him to John Cohen’s Humanistic Psychology, Chapter 1, “The Difficulty of Making the First Step,” where he discusses the pervasive effect on a theory of the initial analogy on which it is based.

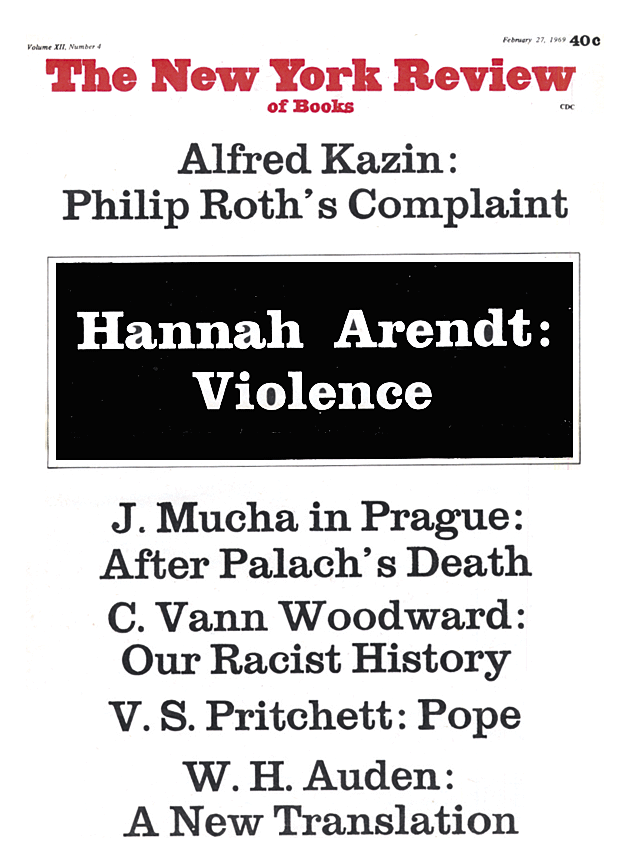

This Issue

February 27, 1969