To the Editors:

As one who on occasion has been an admirer of Ronald Steel’s writings, I was dismayed and saddened to read his review of Robert F. Kennedy’s Thirteen Days. It is ill-informed; there are gross inaccuracies; and several quotations are so wrenched out of context that the result is simply the opposite of truth. And his overall judgments and conclusions are sometimes not only questionable as scholarship, but naive and simple-minded.

On the questions of quotations out of context, consider the following. Steel writes: “What happened was nothing less than a failure of intelligence, ‘a failure,’ in Hilsman’s words, ‘not of rationalization, but of imagination—a failure to probe and speculate, to ask perceptive questions of the data, rather than of explaining away the obvious.”‘

But turn to my book, to the conclusions of my chapter, “The Intelligence Post-Mortem: Who Erred?”, where one would expect to see my final judgment, and what do you find? “Given the inherent difficulties of espionage and the special circumstances…it is probably something to be proud of that the missiles were discovered as early as they were. In sum, Cuba in 1962, it seems to me, must be marked down as a victory for American intelligence—and a victory of a very high order.”

Now that is just exactly the opposite of what Steel says my views are. Where did he find the quote he cites? He found it in an earlier part of the chapter, in a discussion not of American intelligence in the Cuban crisis, but of a small sub-unit of CIA involved in shipping intelligence, and the “failure” I speak of was the failure of this tiny sub-unit to report to higher authority that two of the ships bringing arms to Cuba had exceptionally large hatches and were riding high in the water, indicating space-consuming cargo. The sub-unit had not reported these facts—which were suggestive, but not decisive—because these ships, one of which had been built in Japan, were designed for the lumbering trade; and since the Soviets were short on ships, the shipping specialists thought it only natural that they should be using these, and so saw no significance in the reports. The part of the quote Steel left out was the crucial part: “The fact that the shipping specialists did not call these facts to the special attention of their intelligence superiors was clearly a failure. But it was a failure not of rationalization…”and so on.

Again, Steel quotes my description of a memo, written the next day, about Gromyko’s meeting with the President, which argued that the Soviets would assume from what was said in that meeting and in earlier meetings with Dobrynin, that Kennedy knew about the missiles. Steel then says, “Yet if the Russians assumed that Kennedy knew, presumably they were not plotting a surprise attack.” The truth is that the conclusion was a major point of the memo, and the President’s plans and actions were based on the judgment that the Soviets were not planning a surprise attack. To quote again from my book (page 201), “The Soviets did not put missiles in Cuba with the intent of using them in a military sense any more than the United States put Minutemen ICBM’s in Montana with the intent of using them.”

And there are many more, either misquotations or straight inaccuracies. It was not “shortly after assuming office” that Kennedy learned there was no missile gap, but in late summer, 1961, following an intelligence breakthrough. And it was not from U-2 flights and Penkovsky that we learned, as Steel asserts. U-2 flights were never made over the Soviet Union after May 1, 1960. And a moment of reflection on what Penkovsky’s job was would reveal how unlikely it is that he would have known. Since Kennedy did not know there was no missile gap until late summer—although he may have begun to suspect it—he could not have decided after the Vienna meeting, as Steel would have it, to let the Soviets know by way of Roswell Gilpatric’s speech. Gilpatric gave his speech in October, and the facts are that the decision to make the speech was made in the days immediately preceding it.

Another quotation from Steel: “Meanwhile reports kept flowing in from agents inside Cuba that missiles much longer than SAM’s were being delivered…” There were in fact only two such reports, as is fully described in my book, which hardly justifies the suggestive phrase, “flowing.”

Still another quotation from Steel: “There were available [for diplomacy] not only the Soviet ambassador and the famous “hot line” direct to the Kremlin, recently installed with such fanfare…” Yet the truth is that the “hot line” was installed after the crisis, and partly as a result of it.

Advertisement

There are many more pieces of misinformation or inaccuracies, but one more will suffice. Steel says McCone “immediately ordered the entire island photographed.” In fact, however, McCone had no such power. The decision could be made only by the President on the recommendation of a high level committee. McCone attended a meeting of such a committee at which there was discussion of the fact that a rhomboid-shaped area in Western Cuba had not been photographed for a month. The SAM’s were most nearly operational in this part of Cuba, and the discussion centered on the risk to the U-2 of making a surveillance flight, and the possible consequences if it were shot down. Nevertheless, the full group decided to recommend to the President that a U-2 be flown, providing great care be taken in planning the exact route it was to fly.

In addition to distorting the meaning of quotations, Steel also uses the technique of the grave question, implying that the answers have been concealed, when in fact they are readily available. “But why were photographs not made earlier?” Steel asks. I have a long analysis of that question in my book and reach some conclusions that Steel should have found interesting. For example (page 186): “It could reasonably be argued that the U-2 flight of October 14 found the missiles at just about the earliest possible date…” I do believe that it could be reasonably so argued, but my own conclusion is that they could have been discovered at least two weeks earlier, but probably not much more. “Given the vagaries of the weather, (page 190) it would have been a fantastic stroke of luck if convincing photographs could have been obtained before September 21…” The decision to fly the U-2 was made on October 4, and the subsequent delay was at the operational level. Time was consumed in planning because of the SAM’s; there was postponement because of weather; and there was a disgraceful squabble between the Air Force and CIA as to who should fly the plane—all of which is fully documented in my book. The point is simply that Steel’s misuse of quotes, his inaccuracies, and his rhetorical questions leave the reader with an impression of mystery and possible conspiracy—yet the facts and the answers to Steel’s questions are all laid out in a book he has read—or at least quotes from.

It is against this background of misquotation, inaccuracy, and suggestive rhetoric that Steel’s major conclusions must be judged.

One of these conclusions is that the Kennedy administration was caught “flat-footed” in the Cuban missile crisis, and that the reason was that the administration “could never figure out why the Russians might find it advantageous to put missiles in Cuba.” Yet the evidence on both counts is in the exactly opposite direction. As described above, a study of the data indicates that if the decision to fly the U-2 that discovered the missiles had been made two weeks earlier, it might have discovered nothing at all. This is not being caught “flat-footed.” And there is other evidence. In my book, for example, in discussing the failure of the shipping intelligence unit to report the fact that two of the ships had large hatches (mentioned above), I wrote (page 189): “All that these reports could do, no matter how seriously they were taken, would be to increase sensitivity in Washington to the possibility that the Soviets would put missiles in Cuba. But the people in Washington, as even the public statements of the time show, were already sensitive to the point of nervousness. President Kennedy made several public statements warning the Soviets. He instituted special security precautions concerning intelligence on offensive weapons. Questions were asked on the subject in every Congressional hearing that had even the remotest connection with Cuba. And everyone in official Washington talked about the possibility constantly.” This is not being caught “flat-footed.”

On the second point, Steel’s charge that the administration could never figure out why the Russians might find putting missiles in Cuba advantageous is simply not true. The September 19 estimate, which decided on balance that the Soviets would probably not put the missiles in, also pointed out that the advantages were so great that the intelligence community should be extraordinarily alert to detect any evidence that they might be doing so after all. The September estimate put particular emphasis on the military advantages, but alluded to others. Then, once the missiles were discovered, the various advantages and motives were fully debated. Again, to quote from my book (page 201); “Judgments about Soviet motives and purposes were inevitably a salient influence on judgments about policy, and even though no one analysis was singled out at the time for formal approval as authoritative, as time went on, knowledgeable opinion tended to converge.” The Soviet decision, I go on to say, “seems to have been an expedient, essentially temporary solution to a whole set of problems—the overall U.S. strategic advantage and the ‘missile-gap-in-reverse,’ the exigencies of the Sino-Soviet dispute, and the impossible demands on their limited resources, ranging from defense and foreign aid to the newly created appetite in the Soviet citizenry for consumers’ goods. The motive was strategic in a broad and general sense, based on the characteristic Soviet expectation that a general improvement in the Soviet military position would affect the entire political context, strengthening their hand for dealing with the whole range of problems facing them and unanticipated problems as well.” It was this fundamental, broad judgment that led to a consensus that the Soviet missiles in Cuba must be removed. For such a sudden upsetting of the world’s balance would set in train events that were unpredictable and that might well bring about confrontations in other places that might be much worse, more likely to bring on a war than Cuba.

Advertisement

I might add that this judgment on Soviet motivations also looks good in hindsight, after additional evidence has come in, by way of such books, for example, as Michel Tatu’s Power in the Kremlin. Tatu, to illustrate, points out the military advantages to the Soviets—the missiles altered “the strategic balance of power in its favor,” and did so with missiles that escaped the United States early warning system. Tatu points out that such a strategic advantage, achieved with relatively small expenditure, was a great boon for the Soviet economy. He then goes on (page 231): “There is no doubt that the move was a gamble, but it was not necessarily bellicose. At that stage of the balance of terror, Khrushchev had no new motives for wanting actually to use the weapons. The missiles like the rest of his arsenal, were meant to intimidate, not to be fired. They were to serve as formidable instrument of pressure on the United States in future negotations and it is conceivable that Khrushchev himself meant to withdraw them some day—in exchange for substantial concessions, of course.” Tatu, in other words, writing later and from Soviet sources, reaches essentially the same judgment.

Steel’s most important conclusion, however, revolves around whether or not Kennedy should have used diplomacy instead of blockade to get the missiles out. Steel seems to agree that Kennedy did have to get the missiles out, that this sudden upsetting of the world’s balance would bring on uncalculable events even though the Soviets did not intend a sudden, surprise attack. Steel argues that instead of resorting to a blockade coupled with a public demand for the removal of the missiles on a tight deadline, Kennedy should have used diplomacy over a longer period of time, and he suggests that it was “party politics” and the upcoming Congressional elections that determined Kennedy’s choice of method and timing.

To support his contention that Kennedy’s motive was politics, Steel again quotes me—to the effect that if the United States were not in mortal danger (i.e., of a surprise attack), then the administration most certainly was. But I certainly had nothing in mind so simplistic as the congressional elections. The theme of To Move a Nation is that policy-making is a political process. “Policy,” I write (page 13), “faces inward as much as outward, seeking to reconcile conflicting goals, to adjust aspirations to available means, and to accommodate the different advocates of these competing goals and aspirations to one another. It is here that the essence of policy-making seems to lie, in a process that is in its deepest sense political.” I meant that the Administration would be faced with a revolt from the military, from the hardliners in the other departments, both State and CIA, from not only Republicans on Capitol Hill but some Democrats, too; that it would be faced with all this opposition at home just at the time that it would be undergoing deep and very dangerous challenges from the Soviets, brought on by the alteration in the balance of power wrought by their successful introduction of missiles into Cuba, and which might well put the United States in mortal danger. This was why the Administration was in trouble. It was political trouble, all right—but the upcoming elections were the least of it—and this was why they had to get the missiles out.

The question of timing, of the tight deadline, was something else again. The reason the deadline had to be tight was the missiles themselves. Steel quotes me as saying that “the two-thousand mile IRBM sites, which were not scheduled for completion until mid-November, never did reach a stage where they were ready to receive the missiles themselves.” The quote is correct, but Steel again chooses what serves his purpose, and leaves out the parts that damage it. He neglects to mention what I said about the MRBM’s, as opposed to the IRBM’s. The MRBM’s would have been operational by October 30th—which is why Kennedy and others on Saturday, October 27th, were talking about “two days”—and that would have meant the Soviets could have launched an initial salvo of 24 missiles followed by a second salvo of 24. Even at it was, Kennedy was taking a risk, for the intelligence community believes, as I describe in my book, that on October 28, the day Khrushchev agreed to pull the missiles out, between 12 and 18 of the missiles were already operational. What is more, the intelligence community believes the IRBM’s were in the large-hatch ships headed toward Cuba at the time of Kennedy’s speech. If the blockade had been delayed, and the missiles reached Cuba, the blockade would no longer be an effective pressure, and it would probably then have taken a much more risky form of pressure to persuade the Soviets to remove the missiles. As I say, it was the missiles themselves that made Kennedy adopt a tight deadline, not the upcoming elections.

The idea of negotiating quietly with the Soviets about the missiles, of using diplomacy as Steel would have it, was discussed in the Kennedy administration, but was rejected for the reason given above. And again, with the benefit of both hindsight and the additional evidence that has come in from Soviet sources, the decision seems to have been a wise one. Pointing out that work on the missiles already in Cuba, the MRBM’s, continued at a furious pace right up to October 28, Tatu says, “It is obvious that if this work could be completed under cover of diplomatic negotiations over broader issues, for example the general problems of foreign bases, Khrushchev would have won all he wanted: not only strategic reinforcement as a result of his newly built Cuban base, but also the diplomatic initiative resulting from his greater strength.”

As I say, I was dismayed and saddened by Steel’s review. These are extraordinarily difficult and dangerous times; and there is much to be learned from the Cuban Missile Crisis that would be helpful in dealing with them. The event deserves more serious and responsible treatment from someone with Steel’s gifts.

Roger Hilsman

Professor of Government

Columbia University

Ronald Steel replies:

As a high official in the last Kennedy administration, and perhaps an aspirant for an even higher position in the next one, Roger Hilsman makes a spirited defense of the motives and the methods of those handling the Cuban missile crisis. He seems particularly sensitive to the suggestion that domestic politics might have influenced the administration’s attitude toward the Soviet missiles—as though such considerations were beneath the dignity of the Kennedy brothers. In his letter, as in his book, he portrays an administration that, while besieged by evil forces from within and without, nearly always seemed to end up doing the right thing. My article was not intended as a critique of his book, which is mentioned half a dozen times at most, but as an analysis of the missile crisis based on Robert Kennedy’s memoir. I wanted to raise some questions which have not been answered by Kennedy, Hilsman, or any other administration officials writing on the subject.

Apparently I have touched a sore spot, since Hilsman, instead of dealing with the substance of my criticism, quibbles over allegedly incomplete quotations, how many weeks constitute a “shortly after,” and what kind of teletype machine links Washington to Moscow. But he does not address himself to the major point of my argument: 1) that Kennedy refused to use traditional methods of diplomacy that might have permitted the crisis to be resolved quietly, and instead confronted Khrushchev with a public ultimatum, 2) that he did so because he needed a foreign policy “victory” on the eve of the Congressional elections, 3) that the intelligence analysts had been obtuse in interpreting data (even Hilsman calls them “a little lazy”) that was flowing into Washington from official and unofficial sources, 4) that the administration did not understand why the Russians might have found it politically advantageous to put the missiles in Cuba (erroneously connecting it with Berlin) and thus was caught flat-footed when the crisis occurred, 5) that the stakes, as Robert Kennedy suggested in his memoir, were not so high as we were led to believe at the time.

Since Hilsman’s objections do not touch on these basic questions, I am really not sure what is the purpose of his letter, unless it be to preserve from further tarnish the reputation of the administration he served. If so, he has not addressed himself to the issues. On the peripheral issues he raises, I would still maintain that the “failure…of imagination, a failure to probe and speculate, to ask perceptive questions of the data, rather than of explaining away the obvious” describes not only a unit of the CIA, as he would have it, but the whole intelligence apparatus, including the one he headed. As for the meeting with Gromyko, if Hilsman advised Kennedy that the Russians were not planning an attack, then Kennedy’s refusal to confront Gromyko with the facts is even more suspect politically, and merely confirms my suspicion that Kennedy wanted a public confrontation with Khrushchev.

I fail to see how Michel Tatu’s speculations offer any “additional evidence” that the Soviet missiles altered the strategic balance of power—particularly since Hilsman agrees with Tatu, and myself, that the missiles “were not to intimidate, not to be fired.” If the Soviets were not intending to use the missiles, why was the administration so desperate to prevent the medium-range MRBMs from being installed? These would have posed little, if any, threat to the American deterrent—as McNamara himself states. Was it the United States that would be threatened, or the Kennedy administration that would be intimidated in its dealings with political opponents at home?

If the threat was not military, it must have been political: the Russians would have racked up a point on the cold war scorecard, they would have damaged the bruised, image of the administration, they would have set up a military foothold in “our” hemisphere, they would have forestalled an invasion of Cuba, they would have helped bridge the “missile gap in reverse,” they would have angered the Pentagon and furnished ammunition for the Republicans. They would have done a number of things—except pose a serious offensive threat to the United States. And in retrospect Kennedy’s behavior could be justified only if such a threat existed—which nearly everyone agrees it did not.

Hilsman, along with many administration defenders, seems to be arguing that Kennedy had to be tough not because the danger from the Russians was mortal, but because the danger from the Pentagon and the hard-liners might have been. Thus in his own words, “…the United States might not be in mortal danger, but the administration most certainly was.” The danger, of course, included not only the loss of Congress to the Republicans, but his “image” before his political opponents at home and his adversaries abroad. Obsessed by the fear that Khrushchev did not take him seriously, Kennedy could not suffer another foreign policy defeat, and identified his own ability to be tough with the nation’s “credibility”—thus the build-up over Berlin, the bomb-shelter scare, the “advisers” to Vietnam, and the ultimatum to Khrushchev over the missiles. The usual defense of Kennedy’s behavior in these cases is that unless he were “tough,” the hard-liners would get hysterical—which is a bit like saying, “Don’t mind me if I burn down our house, because if I don’t that crazy guy next door might do something irrational.”

Like many academicians recruited into the government and transformed into administrators of the American empire, Hilsman seems to consider politics as something more base than “policy.” It is certain, however, that the Kennedys did not. President Kennedy knew that he was in trouble, not only from hard-liners in the Pentagon and on Capital Hill, but from his less-than-inspiring record in office. Heavy Republican gains would have killed chances for passing his legislative program. He certainly did not want to face a crisis in Cuba on the eve of the Congressional elections, but when photographic proof of the missiles became available and the Republican charges could no longer be denied, Kennedy needed a “victory.” He did not have time to seek a diplomatic solution that would have involved negotiations dragging on for weeks—not because a few MRBMs represented a deadly threat, but because the elections did.

In retrospect it might have been better had Khrushchev completed the Cuban bases, and they were then used as a basis for negotiations over broader issues. Not only would we have been spared the dangers of marching to the nuclear brink, but we would have been denied what Hilsman calls “a foreign policy victory of historical proportions.” That “victory” inspired the euphoria of power that led Lyndon Johnson to become obsessed by the imperial adventure launched so “idealistically” by Kennedy and his advisers. But I would not expect this view to be shared by Hilsman, who not only was a high official of the Kennedy administration, but a leading advocate of such Kennedy misadventures as the “strategic hamlet” program in Vietnam. Now that the empire has begun to crumble, some of its intellectual underpinnings are beginning to seem increasingly flimsy.

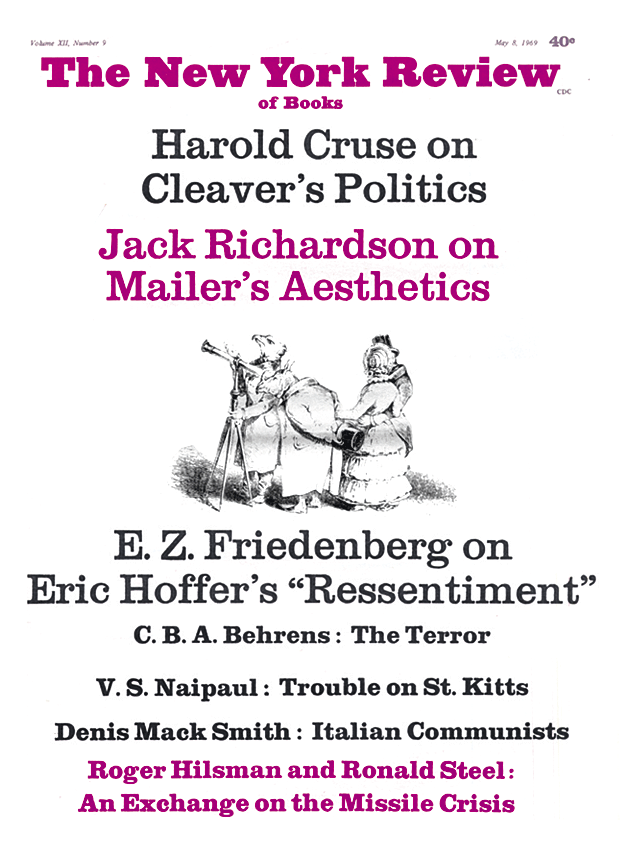

This Issue

May 8, 1969