In response to:

Historical Justice and the Cold War from the July 10, 1969 issue

To the Editors:

I don’t quite understand Professor Morgenthau’s conclusion [NYR, July 10] that “historic truth, tempered by charity and understanding, may emerge from the dialectic of opposite extremes.”

The official version makes Russia the prime cause for the beginnings of the Cold War, Professor Kolko’s version reverses the terms. The two antithetical extremes will merge and the final synthesis will satisfy everybody. But I don’t see any place where the blood and bones of the victims of the Cold War will fit into this marvelous dialectical scheme. I can’t see what synthesis will reconcile the rape of Czechoslovakia and the rape of Greece.

If we must have a synthesis I would like to quote Professor Noam Chomsky in this respect: After decades of anti-Communist indoctrination, it is difficult to achieve a perspective that makes possible a serious evaluation of the extent to which Bolshevism and Western Liberalism have been united in their opposition to popular revolution.

Dimitri Sotiropoulos

Ball State University

Muncie, Indiana

Hans J Morgenthau replies:

Mr. Sotiropoulos misunderstands my position. It never occurred to me that “The two antithetical extremes will merge and the final synthesis will satisfy everybody.” The two extremes will remain as the expressions of two different perspectives from which historic reality is perceived. But each will now be aware of the other’s legitimate existence. It is this awareness that increases our understanding of history.

Bolshevism and Western liberalism have been united in their opposition to popular revolution only temporarily and for entirely different reasons. For the West, that opposition has always been a matter of ideological principle. For Stalin, it was a temporary expedient resorted to towards the end of the Second World War in order not to upset the applecart of the alliance which Stalin saw threatened by the West, making a separate peace with the Axis and withholding economic aid from the Soviet Union once the war was over. As soon as the international situation removed these reasons for restraint, Stalin used again the Communist parties throughout the world in the most pragmatic fashion in support of the national interests of Russia, encouraging and supporting revolution here and making elsewhere deals with governments suppressing their Communist parties.

There is no opportunity for a synthesis here either; for we are here in the presence of policies that are different in their essential qualities even though they may coincide sometimes in their immediate moves.

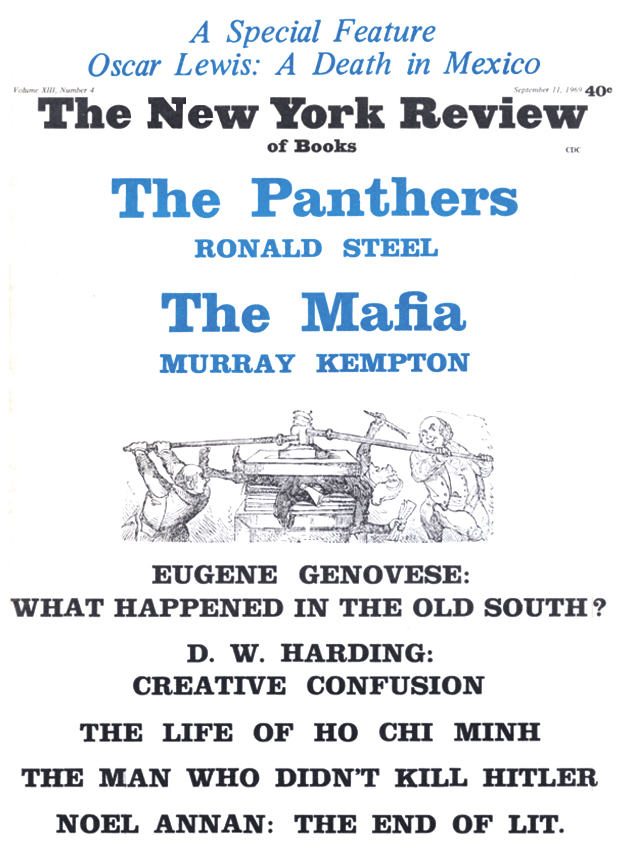

This Issue

September 11, 1969