In the current situation of chronic crisis and intermittent polarization on the campus, and in the country as a whole, what can the professional intellectual do? Especially what can he do if he is an academic intellectual, strongly opposed to the current drift of American society, yet equally strongly committed to certain liberal values, such as rational inquiry, intellectual freedom, tolerance, and civilized discourse, values that some sections of the extreme left now vehemently reject? Does this kind of liberal commitment sooner or later force one inevitably and reluctantly into the arms of those who call the police, and thus not very indirectly into the arms of the military and all those forces responsible for the cruelties that pass under the name of law and order in western civilization?

One answer comes to mind, based on the famous remark attributed to Florence Nightingale: Whatever else hospitals do, at least they should not spread disease. We can paraphrase it thus: Whatever else academic intellectuals do, they should not spread myths.

Let this homely version of the categorical imperative serve as a starting point from which to take bearings. Those who attack myths frequently do so from a perspective that itself rests upon mythical assumptions. There is no perfect cure for this situation—least of all confidence in one’s own infallibility. Nevertheless, the liberal ideal does contain one very powerful antidote. It is the assumption that no idea should or even can be permanently preserved from rigorous critical scrutiny. That assumption or ideal seems to me the essence of the concept of tolerance and intellectual freedom. It means something quite different from the notion that everybody has a right to his own opinions.

That notion may be the first myth that it would be wise to get out of the way. In a strict sense, there is no such thing as a right to opinions. I have no right to believe what is manifestly false, or even what is only moderately likely. All that exist are grounds for opinions, warrants for belief, based on logic and fact. Some of these warrants are much stronger than others. Many of them turn out upon examination to be rather feeble. In a reasonably good university nowadays very many of the most important warrants—pace radicals who see the university as mainly a factory of technical skills and social polish for the managers of the status quo—are undergoing severe re-examination. Thus the liberal commitment to intellectual freedom is a commitment to a process, not to a specific set of beliefs.

Like all commitments it is open to challenge. The eighteenth- and nineteenth-century faith that this process would soon make the world a better and happier place to live in now seems absurd. There is no real guarantee that it can do anything of the sort. On the other hand, there is plenty of evidence to show (a) that once the process has gotten started it is very difficult to stop; and (b) that political efforts to stop it cause enormous misery which extends far beyond the fate of the immediate victims. Finally, unless one wants less rational grounds for belief rather than more rational ones, no other commitment is possible.

Very likely most people, including even acute professional thinkers, by and large would prefer less rational grounds in the sense of more emotionally satisfying ones. The danger that the world will soon lose its mysterious and mythological qualities is probably a romantic exaggeration. That observation takes us back to the starting point, the mythological bias and possibilities of self-deception in any attack on prevailing myths, the hint of arrogance in any effort to stop their spread. Both liberal and radical traditions come to the aid of any thinkers with honest misgivings on this score. Since there is enough freedom here to allow intellectual opponents to leap at the opportunity to pluck motes and beams from the eyes of anyone so rash as to commit thoughts to paper, there is not much risk that such arrogance will be seriously misleading.1

In the study of human affairs, critical rationality is most effective when it asks embarrassing questions about what we would like to believe. That is roughly the way I shall try to proceed in endeavoring to locate the dangers to the process of rational inquiry and hence to intellectual freedom. A substantial number of basically humane academic intellectuals remain most reluctant to acknowledge that the central threat to their values derives from fundamental trends in modern society itself. In other words, the threat comes from and through the Establishment, an imprecise term but one that refers to something very real, of which they form one part.

Here I shall not try to separate out the strands of truth from those of exaggerated rhetoric in neo-Marxist and other radical analyses because that is a difficult and complicated task, one I am doing my best to execute elsewhere. It is sufficient to repeat what is becoming increasingly obvious to many: In American society there are enormous structural obstacles to the humane and constructive use of our tremendous technological power. Partly, though not entirely, for these reasons this frightening power takes destructive forms, finding as its main victims those with dark skins and wretched lives in the economically backward sectors of both American society and the world at large.

Advertisement

The reasons why many academic intellectuals fail to perceive this threat are also fairly clear. To those past the draft age the Establishment poses no physical threat, at least so long as it is able to avoid the prospect of nuclear war. Indeed, the established order is the source of their substantial comforts and privileges. Hence the threat takes the insidious form of a temptation to avoid raising embarrassing questions.

Though the temptation is probably a lot stronger now than it was even a generation ago, owing to the massive inflow of government funds, it would be a serious error to conclude that the threat from the Establishment was either really new or really material. All societies have quite effectively controlled their educational institutions in the interests of the dominant groups. Contemporary societies may indeed be historically unique in their incapacity to take effective charge of educational institutions. More important for our immediate concerns is the fact that the Establishment does actually permit and even encourage a great deal of intellectual latitude. Some research sponsored by the military, I am assured on excellent authority, has at least until very recently been very “open” and free of petty bureaucratic vexations, because Congress has not been inclined to meddle.

Most academic intellectuals over forty perceive threats to intellectual freedom in terms of meddling or something stronger that approaches direct physical intervention or threat: censorship, legislative investigations, threats of prison and concentration camps at the hands of movements and governments that scorn or attack liberal democracy. Their own education, together with the experiences of fascism, communism, and the McCarthy era, impel them toward such a perception. These were very real threats, and they have left their imprint as a framework for the interpretation of subsequent events. Since the established order in so-called normal times poses no such threat of direct intrusion, and indeed supports considerable latitude, and since the activist radical students do pose exactly that kind of threat, it is scarcely surprising that to the senior faculty, by and large, the extreme radical students appear as the real danger.

They are a menace, even if a derivative one, a response to trends in the larger society. Both white radicals and black radicals—separately and, so far, much more rarely in combination—threaten and despise critical rationality. Certainly not all of them do. But some do. It is no service to anyone, least of all to simple truth, to deny the existence of the mood, manner, tactics, even strategy of the left-wing storm trooper. Though there are very rapid fluctuations in anything so intangible (yet so real) as currents of student opinion, there are some reasons for fearing that the secular trend against critical rationality may be an increasing one. Nevertheless, the important task for the moment is to understand why it exists. How does the cluster of values and practices that I have called critical rationality look to radical students? Between whites and blacks there are crucial differences that make it necessary to comment on each separately.

Amid the huge variety of psychological, sociological, and historical explanations of white student radicalism, two theses stand out, I suggest, as corresponding most closely with the evidence, especially the American evidence. In the first place, the immediate historical experience of anyone born around 1950 has been one during which the more repulsive aspects of liberal capitalist democracy became highly visible, while the “classic” enemies of freedom during the Thirties and Forties, fascism and communism, both changed their character and became something to learn about from textbooks. That this change in visibility corresponds only partly with what happened does not diminish its significance. Along with this change in the visibility and character of cruelty and suffering—indeed part of this change—has been an increasing contrast between ideals taught in both upper middle-class homes and good universities and the actual state of affairs in the outside world. Thus the young radicals have been both acting upon their elders’ ideals and rebelling against their betrayal, struggling to see what went wrong, and searching desperately for substitutes. The draft brings all these issues out of the realm of dormitory arguments and into the realm of agonizing personal decisions. Simultaneously, at a time when they are still partly outsiders within a continuing academic community, these students become acutely conscious of the way in which liberal values, such as freedom of research, serve to protect vested faculty interests, including the right to work for the Pentagon, which they perceive quite correctly as supporting under present circumstances the forces of cruelty and repression.

Advertisement

Because black students are outsiders in a deeper and more fundamental sense, they embody a different constellation of factors. Once again I shall not try to discuss all black students any more than all white radicals, but only certain trends that appear especially significant in view of the conception of critical rationality and intellectual freedom advanced above. Perhaps the most important fact here is the impact on black students of militant movements within black communities. At least in their rhetoric, these militants reject the workings of white society in almost all of its features. The rejection of rationality too as something racist, inhuman, and domineering—the weapon of those who enslaved the blacks and destroyed their minds and souls—plays a part in all this (sometimes with the help of arguments developed by white romantics of the nineteenth century). Let me add that their indictment is not totally nonsense, though a great deal of it is. Along with this rejection there exist among black students searches for a black identity, partly to override class and factional differences within their midst, partly as a charter myth to serve as the basis of legitimacy for their fight against white oppression.

Black students, then, who find themselves within the relatively sheltered environment of a university are often the objects of a certain amount of contempt and suspicion from these militants. Sharing at least some of the general militant resentment, as soon as they form a sizable and visible minority within a university, black students feel a need to justify their presence there. Along with other factors this pressure leads them to respond favorably to student militants who appear within their own ranks. The result is an inflammable minority. So far, as in the larger black communities, the flame has been used to put heat, often quite effective heat, behind immediate and concrete objectives, rather than revolutionary ones. There is the same gap between rhetoric and actual behavior that characterizes the black communities and movements in general, as well as other protest movements (such as the labor movement in some countries) at certain points in their development.

In many universities the basic situation is one in which academic liberals find that they have been granting reforms in which the black beneficiaries are not interested or, perhaps more precisely, in which developing circumstances have prevented the beneficiaries from taking much interest. This situation contains at least two major threats to the university’s efforts to remain and become a place of free inquiry. White liberals may be unwilling and unable (for it is no simple task) to select those aspects of the rational tradition that deserve and require defense against the myth-making propensities inherent in the search for black identity. Maintaining standards of rigor, accuracy, and objectivity, and facing disagreeable consequences often look to black students like the imposition of “white standards” except in those instances where they lead to results unflattering to western culture and its achievements.

In some segments of the faculty, uneasy resentment against these romantic and anti-intellectual trends among the black students could conceivably give rise to pressures to get the black students out of the university or more likely de facto out of the way. If influential faculty members sense that black students more and more do not want a “white” education; furthermore if faculty members become resentful over having to make slots for black students and thereby keep out more highly qualified and motivated white students (an uncertain proposition in the light of increasing alienation among many of the most talented white students); and, finally, if they become more and more angry about the frequent interruptions of normal academic operations by black militants, the demand to remove black students from the “regular” campus might become quite powerful.

Instead of setting up a separate physical plant, which is much too expensive, the removal can take the form of increasing the social and intellectual exclusion that already exists for reasons of mutual repulsion. The result would be a repetition within the academic scene of the situation in the larger society: separate but highly unequal education, a militant ghetto uneasily contained within the larger group. In view of what a university is supposed to accomplish, both sides would lose heavily. The whites would lose the advantages of critical exposure of their own myths from the black standpoint. And the blacks would be cut off from critical exposure of their myths, as well as the opportunity to acquire skills and knowledge that would be useful no matter what they can and do decide is to be their individual and collective fate. That this pessimistic prognosis is no firm prediction goes without saying. There are significant counter-forces at work, especially in the white liberals’ strong desire to prevent such an outcome. At the same time, a clear recognition that the possibility does exist is one prerequisite for efforts to prevent its occurrence.

For all their bitter internal differences, black and white radical students (and their faculty sympathizers) share one trait. The situation drives them toward adopting the strategy and tactics of the powerless. They have only too many good reasons to be highly skeptical and impatient about the real effectiveness of the slow ferment of rational discussion when it comes up against well-established patterns of thought, old habits, vested and material interests, the whole complex inter-twined with and supported by strong forces in American society itself. For example, facing the concrete problem of scientific research and the potential or actual repressive applications of that research—under sponsorship that makes such application seem highly probable—radicals can ask themselves: how can a slowly changing climate of opinion possibly compete with the golden flood of temptation,2 the pressures for career choice, the apathy of most students and faculty?

In this setting, many students who try to work “through channels” and who come to take part in the process of debate and discussion, with very little real power but with liberal if critical inclinations, easily turn radical as they perceive the slowness of the whole undertaking, a pace which to faculty members may seem unduly hasty and ill-considered. Later, out of a mixture of desperation, moral fervor, and cool calculation (the proportion of these ingredients may vary), a very small number may then decide on the now familiar “confrontation tactic.”

The essence of this tactic is to do something in the name of a good cause that will compel the university to call the police or, more fundamentally, to engage in some form of behavior that will dramatically expose the hypocrisy of the university’s claim to be a place of rational discourse and its subservience to the forces of repression in the larger society. In this connection, and indeed more generally, it is usually futile to tell radicals, or at least many radicals, that their acts run the risk of increasing repression and intensifying neo-fascist trends. For these radicals “causing fascism” means nothing more than bringing the inherent character of the system to the surface anyway. What impresses them is the “normal,” necessary, and structurally induced cruelty and waste of contemporary American society.

The tactic “works” if there is fairly widespread support for specific radical objectives; that is, if the action is legitimate according to the still predominantly liberal climate and if the response of the authorities appears to be the overwhelmingly aggressive one. Calling in the police to oust students from a building sends a shock wave of sympathy for the radicals through the student body and part of the faculty. Out of the shock wave there comes some slight increase in forward momentum toward the immediate radical objective, such as the reduction of ties with the Pentagon and the infusion of more social conscience into the university’s real estate policies. In urban universities these policies generally affect black communities. Perhaps more important from the radicals’ standpoint is that a few more students turn completely and definitely away from their studies and the prospect of careers in the prevailing order, while the anxiety and uncertainty of many others increase.

On the other hand, the device “fails” where the student radicals by their tactics put themselves in the position of the aggressors who resort openly and prominently to violence. The pseudo-guerrilla raid, in which a small band of radical students physically attacks and beats up professors (and secretaries, the forgotten individuals in most of this turmoil) thought to be tools of the more sinister aspects of the Establishment, still sends the opposite kind of shock wave through the university, especially when the attack comes out of the blue. Even among many who are sympathetic to the radicals the response has been one of disgust and revulsion. Such at any rate has been the case in the United States. (Where the cultural climate differs in some respects, as in France, the results also differ. There the polarization is sharper. Leftists by various rough tactics have sought to block the implementation of reforms that might preserve a system they detest. In so doing they have brought to the surface latent rightist movements. The two have been struggling for control of different sectors of the university system and could conceivably establish areas of hegemony in separate parts of it.)

What will be the ultimate outcome of the insidious threat to the university from outside its walls and the derived but more obvious menace from within, it is of course impossible to predict with any confidence. In the course of their bitter factional disputes the American radical students show signs of learning that the attempt to change society through the university is like trying to pry up a stump with a bamboo crowbar. Even those who care little about the crowbar find the method slow and ineffective.

In any case, trends in the society as a whole will play a major part in shaping the result. Both inside and outside the university there is the possibility that the prevailing semi-legal toleration of professed revolutionary movements may shake down into a more permanent arrangement. Though neither the revolutionaries nor their opponents can possibly afford to acknowledge the fact, there are some signs that a tacit code of conduct to govern the behavior of each is emerging. If such a code takes hold, the revolutionaries would be allowed to indulge in as much rhetoric as they chose and a certain amount of violence to keep alive the flames of revolutionary hope. But there would be certain boundaries (as yet dimly defined) that they would not transgress, that they would even keep their own members from transgressing, out of a variety of prudential and moral considerations, just as out of similar considerations the dominant groups refrained from trying to “clean up the mess for good,” that is, total extermination of the radical opposition.

A slightly more hopeful prognosis would hold out the prospect that radical actions could yield liberal reforms. There are reasonably good grounds for thinking that past liberal reforms have to an important degree resulted from radical prods; these reforms have at other points followed full-scale revolutions. The Revolt of the Netherlands, the Puritan Revolution, the French Revolution, and the American Civil War did help to break down certain institutional obstacles to the establishment of western liberal democracy, though it is of course impossible to prove that they were necessary to achieve this result.

But liberal reforms sparked by radicalism did occur only where, and because, for other reasons, there had grown up a widespread commitment to liberal values and a demand for liberal institutions. Where these additional crucial intellectual ingredients and their social carriers were lacking, the outcome of revolutionary and radical prods has been very different indeed. And in the world at large, liberal institutions and ideals, like those of any other successful movement, show clear signs of historical obsolescence. So, for that matter, does the Russian brand of communism.

The most pessimistic prognosis perceives student radical movements today and the responses to them as part of a general unraveling of the whole social fabric under the stress of new and unprecedented strains, a disintegration that will eventually lead to the rejection of any and all forms of authority and to a chaotic barbarism, a war of all against all, in which life will be nasty, brutish, and short, if it is possible at all. Without wishing to discount this possibility altogether, I can see some reasons for finding it rather extreme. Two processes actually seem to be at work. The general unraveling of existing social fabrics has been going on for a long time, and at an especially rapid rate since the beginning of this century. There has also been at work a process of forced reintegration by both revolutionary and counterrevolutionary methods. Either one can gain mass support, or lose it, depending on circumstances that are only imperfectly understood.

In this sea of uncertainties, about all there is to cling to is one firm conviction. I submit that there is plenty of evidence to support it. Any future society that does not preserve and extend certain traditional liberal values, such as the right to criticize prevailing beliefs and corresponding rights giving protection against the arbitrary abuse of authority, will not be a fit society for human habitation. It will be unfit not only for intellectuals but also for practically everybody else.

This conviction can provide some rudimentary guide lines. In an acute crisis there is not much one can do. The crisis, however, is a chronic one with intermittent acute flare-ups. Even if the flare-ups should lose their intensity or disappear, burning issues are almost certain to plague academic life for the foreseeable future. Within universities there is precious little agreement among the various contenders about what they want to accomplish, what they want to change, what they want to defend, indeed, and perhaps most important of all, what, if anything, is worth defending.

That situation is by no means altogether unhealthy. It is part of the general disintegration of a unified medieval view of the universe and man’s place therein (was it really so unified?). This transformation has come about largely because of the corrosive influence of critical rationality, which has by now turned back upon many of its own prior achievements. For the modern thinker, one consequence has been the enormous widening of intellectual options. Generally part of the price of abandoning errors and discovering new truths is emotional turmoil and confusion.3 Nevertheless these are scarcely virtues in their own right, and are an additional danger to processes of rational thought.

As we have already had occasion to notice, one specific form this danger often takes is the misapprehension derived from intellectual responses to past experiences. Principles hammered out during previous struggles, and which do have significant merits, turn into universal rules. Indeed, the emotional appeal of the principles derives from their original claim to universality, as occurred when liberal ideals were part of a general offensive against entrenched privilege during the eighteenth and part of the nineteenth centuries. As circumstances change, if the facts that these principles once deemphasized or omitted become more important, the consequences of an emotionally stubborn defense could be disastrous. All this is familiar enough from the fate of classical economics between the time of Adam Smith and our own. In intellectual struggles, as in military ones, a stubborn defense of an untenable position can lead to a disaster in which valuable truths perish along with serious errors. That is the case with liberal ideals in general. It is especially so with certain conceptions of academic freedom. By a curious twist of fate they happen to be on an exposed and active sector of the front.

From this perspective three aspects of the ideal of academic freedom are especially significant, and widely taken for granted. The first holds that all political pressures on the academic intellectual are equally bad; that all deserve to be rejected. It is not very difficult to perceive in a somewhat theoretical fashion that this position is untenable. From the viewpoint of a simple commitment to truth alone there are good and bad political pressures. In informal and more concrete discussions most academic scientists are likely to agree that the kind of political pressures that led to the useless experiments of the Nazi doctors on concentration camp victims during World War II deserve the utmost resistance. That, almost anyone can see, was a horrible perversion of science.4 When comparable pressures are exerted today, many academic liberals are much more reluctant to perceive and resist them, partly because these pressures take the form not of physical threats but, as noted earlier, of temptations and opportunities. Though resistance to such pressures has commenced and is increasing, so far it remains rather ineffective.

The second idea is that it is possible to make scholarly and scientific decisions that have no political component. They are supposedly matters of pure knowledge. Along with this idea, perhaps indeed part of it, is a third partial truth that becomes dangerously misleading when taken as the whole truth. Since it is impossible to foretell what kinds of knowledge may turn out to have significance in the future, all forms of inquiry deserve to have an equal opportunity. This idea links up with the first—for the three form a reasonably coherent whole—through resentment against any kind of political pressure or political consideration in resolving intellectual issues.

Once again it is not too difficult to see that the last two ideas are untenable and that the attempt to carry them out literally and rigorously leads both to absurdities and to results abhorrent to the humane elements in the liberal tradition. Limitations on human and intellectual resources make it impossible to pursue all lines of inquiry simultaneously. Hence choices are unavoidable. The political component enters into both the making of these choices and their consequences. It forms part of the diffuse sense of priorities that governs every discipline, even the most abstract ones. No mathematician is likely to seek (or obtain) a huge grant for working out the values of pi to a few hundred more decimal places. It is just not thought to be worthwhile. But what is thought to be worthwhile, the kinds of questions that scholars and scientists ask and do not ask have enormous consequences for the kind of life everyone else leads. Since the kind of life we lead is what politics is all about, these issues are political ones.

These issues have gained salience in recent times through radical attacks on the “myth of university neutrality” and the demand for “relevance.” The cry of relevance in turn becomes a cover for all sorts of historical and cultural provincialism and the demands of special interest groups. The cry for relevance becomes just one more obstacle to the serious consideration of fundamental issues, a mirror image of the demand that universities become service stations for the status quo. In the face of such demands the university is paralyzed, because its own myths lead to the rejection of any conception of a coherent intellectual strategy, any general grounds that would enable academics to say, for example, that knowledge about human heredity is more important than information about some fourth-rate political scribbler.

The curriculum thus becomes more and more of a cafeteria. Since it is impossible to claim that it represents the outcome of any defensible and rational intellectual process, any sensible use of resources, academics are forced to waste time either discussing the curriculum again and again, or else raising the absence of strategy to a virtue. To have no way of distinguishing significance from triviality is scarcely a proud badge for professional thinkers. In theory it amounts to conceding the right of the strongest. In practice it means that the university sells its services to the highest bidder and makes concessions to those who kick it the hardest.

Somewhere down that road lies death with dishonor. To be sure, a university can still “exist.” It can continue to exist by becoming nothing more than a service agency for the status quo, stifling all critical voices. Conceivably a university could even become a service station for revolution, though that is much more doubtful. So far universities have only been service stations for revolutionary regimes after they have themselves become new forms of status quo. Nevertheless, a university that exists only as a service station for either the status quo or the revolution has ceased to be a place where people can think freely, where critical rationality can exist at all. A university where a professor cannot on some occasions and with some real effect say “the people be damned” is not worth having. Nor does a university deserve its name where it is impossible to make similar and effective observations about the exalted of the world.

These remarks imply that there has hardly ever been anything that really deserved to be called a university, a position with which I see no reason to quarrel. It is something to strive for, not celebrate.

To the extent that the preceding analysis is correct, it means that the obligations of critical rationalism do coincide partly, but by no means completely, with major radical currents. The critical rationalists will have to take on some of the radicals’ tasks and, if they are to succeed, will have to perform them more effectively and in some ways that are different. Whether they can succeed, whether either they or the radicals can succeed, are separate issues. Furthermore, even the immediate tasks are not identical because the final purposes differ.

Radicals today of course vary enormously in their conception of the future society that will emerge from present and future contests. But what will the new social order look like? A great many radicals imply that it is impossible to present a blueprint in advance, accusing those who demand such information of engaging in unfair polemical tricks. They argue that it would have been impossible for the “bourgeois revolutionist” to anticipate capitalist democracy before it actually came into existence; on what grounds then should one expect more of contemporary revolutionaries?

Here, I think, the radical argument is mistaken. One can make a good case for the proposition that Adam Smith anticipates the central social mechanisms of nineteenth-century competitive capitalism. In any event, liberalism, capitalism, and democracy grew up both within and against various forms of an ancien régime. It was, one should note, a very long, drawn-out process. By the eighteenth century a social critic had plenty of partial working models around him upon whose experience he could draw in criticizing the present and projecting into the future.

Today, on the other hand, those radicals who reject both western liberalism and Soviet communism have very little upon which they can draw in the way of models: bits from Cuba and China and Vietnam and the guerrilla tradition. The relevance of any of this experience to advanced industrial society is doubtful. For western revolutionaries none of this actual revolutionary complex is part of their daily life in the same way as early capitalism was for past social critics. With far less experience to go on, and that much more remote, if not exotic, the present-day western revolutionary is free to be much more of a romantic—and to reject notions of intellectual responsibility as mere props for a cruel status quo. Regardless of the shape or shapelessness of the society to come, many radicals agree that the future will be so qualitatively different from the present that the problem of safeguards against abuse will become trivial.

The critical rationalist finds this claim impossible to swallow. Skeptical that any institutional changes, no matter how necessary they seem, will ever lead anywhere remotely near perfection, the critical rationalist retains a powerful interest in seeing to it that opportunities for rational discussion and criticism continue to exist. To the extent that he also believes it is impossible to dismantle anywhere near completely the apparatus of modern industrial society—or that attempts to do so can only lead to catastrophe in a different form—he cannot easily avoid the conclusion that human society will continue to exist in the form of large and complex units that from time to time will be at war with each other. Should these units manage to avoid exterminating each other, a prospect about which there is no reason to be especially sanguine, the best one can anticipate is the continuation of specialized institutions that will have some recognizable resemblance to the traditional ideals of the liberal university. It is not an outlook that sends one screaming to the barricades.

From this general assessment there follow certain obligations for the academic intellectual. The first is to try to uncover and expose the roots of violence and the threats to human freedom that derive from the prevailing social order. Under present and foreseeable circumstances in the United States this conception of his obligation places the critical rationalist in sharp opposition to official liberalism as expressed by political leaders, including those in the left wing of the Democratic party. The task of critical exposure of course runs much wider and deeper than concern with the ephemera of daily politics. Even more broadly conceived it is not everyone’s job. But it is a crucial one, and shared with certain radicals. At the same time, the academic intellectual has the equal obligation to avoid capitulation to the intellectual provincialism of the oppressed and the pseudo-oppressed. In social action, which is much less part of the academic intellectual’s métier but not necessarily excluded from it, there is an obligation to work for the removal of institutions and abuses that threaten to overwhelm what there is of an open society, and to do what is possible to establish such a society.

More concretely, with respect to the everyday life of existing universities this position implies an awareness that the pursuit of knowledge unavoidably has political consequences. It is impossible to foresee many of these, especially as some of the most important ones may well lie in a distant future. Nevertheless, professional thinkers should see to it that these consequences are as far as possible humane and constructive ones, that they reduce rather than increase the amount of misery and cruelty at large in this world. What are humane and constructive purposes change with historical circumstances, and from this standpoint remain forever open for redefinition. In discussing both the means to attain them and the ends themselves, anyone who adopts this stand will realize that the choices are seldom unequivocal and easy, that all of them may involve serious costs.

The most difficult intellectual task, therefore, will often be to distinguish between serious argument and specious rationalization. Adherence to this view of the world therefore implies a large measure of courtesy and detachment that nevertheless stops short of both blandness and intellectual irresponsibility. Finally, the conception of humane and constructive purposes does not only include working for the removal of specific evils and abuses, even if their stench reaches to the heavens. Trying to be humane also includes giving a large place to the search for truth that widens human horizons in time and space and for the beauty that enriches it. These too are political conceptions for they are part of what makes life worth living. Here too there is an obligation to be aware of the cost, to realize that the costs are not readily measurable—perhaps in a deeper sense not measurable at all, since those who pay them may use a different moral and intellectual currency—and hence to make a serious effort to see that the obvious material costs do not fall upon those least able to pay.

This conception presupposes for its full development a form of society that has never existed. Meanwhile attempts to approximate it, it is often asserted, are passing from the historical stage. Perhaps that is so. Are critical rationalists like intelligent pagans in the last phase of classical civilization? Probably with some violence to the historical facts, in moments of relaxed musing one can imagine a pagan thinker sufficiently intelligent and humane to perceive that the Roman Empire was cruel and corrupt, that its rationale was nonsense which no intelligent person could take seriously any longer. If this pagan had a slightly sensitive conscience, he might be uncomfortably aware that the soldiers on distant ramparts, whose plundering he criticized, still somehow indirectly supported not only his own privileges and right of detached contemplation but also the liberties of those who more radically attacked the social order, as in fact Symmachus taunted the Christians. If he were curious too, he would of course make every effort to gain a sympathetic yet critical understanding of the new forces of ferment and change in his world, the Christians and the myriad sects with whom they competed and quarreled. And if he were at all successful in his effort at understanding, he might gain at least some dim sense that for a long time to come these new forces could only create something much worse: that out of the rhetoric of brotherhood there could easily come bloodshed, chaos, heresy, persecution, the Crusades and the Inquisition….

Someone who reflects along these lines soon comes to realize that human civilization has never been arranged mainly for the benefit of the doubters and the skeptics. A moderately thoughtful person will not waste much time in self-pity on that score. The world is too full of terror and wonder, which cry out for the effort at disciplined understanding; there is just too much work to be done for indulgence in this form of luxury. The critic should also be modest enough to realize that the role of doubter and skeptic is not the only one in the human drama. Therefore such a person will not try to force this role upon those unsuited to taking it.

At the same time he, and nowadays fortunately she, will take due pride in this role so long as it remains at all a possible one. Just as they do not force this role upon others, and respect those who act in very different ways on behalf of humane ideals, they will insist on respect for their own role, for the freedom to choose it, and resist with whatever force and courage they can command any attempt to deprive them of the right to take it. They will not be afraid to call in question the inevitable, which, in the words of C. Vann Woodward, needs all the opposition it can get because it is usually unpleasant. And, one may add, the inevitable is seldom what anybody expected.

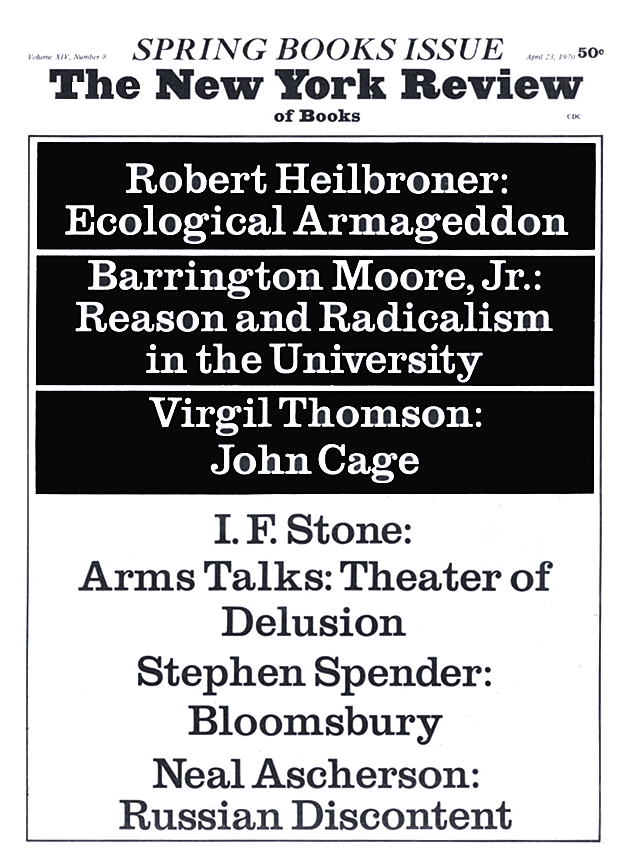

This Issue

April 23, 1970

-

1

There is also enough good solid human spite for many critics to want to pluck out the author’s eyes as well. Spite has not yet received its due as an engine of intellectual progress. ↩

-

2

If the golden flood of temptation sharply diminishes, as now seems probable, the situation may develop in the direction prevailing in France, where the absence of suitable career outlets creates further doubts among the young about the legitimacy of the prevailing system. The new situation could extend the potential mass base for student radicalization. ↩

-

3

Premature attempts to restore a unified view (if indeed one can ever be restored), to do so rapidly and by force majeure, lead of course only to terrorist regimes. The neo-anarchist hopes of the New Left are in my judgment, and for reasons to be given elsewhere, unworkable. Attempts to put them into practice on any wide scale as the basis of a new society are a reasonably effective prescription for another form of disaster. Whether it is a more effective prescription than the continuation of what exists is a question for which no precise answer is possible. ↩

-

4

The liberal will of course point out at once that the two situations are different, that in a democracy there are means for protest against such hideous perversions. The effectiveness of these means is what the radical in turn denies. Hence the issue is in part a straightforward factual one that could in theory be resolved by an appeal to the evidence. Fortunately, some on both sides are still willing to make the effort. But the differences become irreconcilable if the radical insists on escalating his conception of “effective” changes toward utopia and the liberal slides toward a pragmatism that justifies anything that happens to exist. ↩