To the Editors:

The Metropolitan Museum is now facing the problem of housing three large, new donations: the Lehman Western European Art Collection, the Rockefeller Primitive Art Collection, and the Egyptian Temple of Dendur. Since 1870 whenever space was needed the Museum expanded into the Park. In 1970 the Museum insists on solving the same problem in the same fashion. It proposes to add 325,000 square feet to the present structure at a cost of over $50 million to accommodate its new acquisitions. Before this amount of public money is spent, whether from federal, state, or city funds or from tax-deductible private gifts, several questions should first be publicly discussed.

The role of today’s museum is not fulfilled by its size, number of works of art, catholicity of the things collected, nor by developing itself into a “fully organized encyclopedia of man’s fifty centuries of aesthetic development,” to quote the language of the Museum. Such a concept is too diffuse and any attempt to carry it out will prove self-defeating. Socially and culturally museums should take account of specific needs and interests of different communities. There is no reason why, instead of encroaching on the Park, the Metropolitan should not decentralize into different parts of the city, following the example set by Mayor Lindsay who has repeatedly urged decentralization of the city government into smaller units in order to better serve individual neighborhoods. Why shouldn’t the new donations to the Metropolitan be easily accessible to people in Queens, for example, or Harlem or lower Manhattan? Why should the Lehman collection, first assembled in a private house, not be on view in one or more of the buildings marked for preservation by the city’s Landmark Commission?

The Museum has no convincing answers to such questions. It claims that only by expanding will it realize its goal, as stated in the Charter, to “reach, educate and recreate the working millions.” The Museum should then define who these working millions are, and elect their representatives to its Board of Trustees so that they can voice their demands and suggest ways to meet them. Community needs can no longer be defined by self-perpetuating private enterprises.

There has been inadequate public discussion and consultation on the merits of centralization as against decentralization. A spokesman for the Museum says, “We will provide whatever the communities tell us they want.” If the Museum has been polling communities about their needs and wishes, why have their findings not been made public? The same Museum spokesman says he believes in decentralization. The Museum should show how it intends to implement this belief before using up all available financial resources on a grandiose plan for even greater concentration.

The need for such proof is further demonstrated by the contradictory statement of a staff member appointed by the Museum to the trustees’ committee on decentralization and community needs that “decentralization is to split up what has meaning because it is together.” The Louvre did not lose its “meaning” by being decentralized. In September 1801 the first redistribution of its works of art was carried out at the expense of the Louvre, and museums in Brussels, Geneva, and Metz were founded. Eugene de Beauharnais carried this decentralization further by creating museums in Italy such as the Brera Gallery in Milan. Decentralization is meaningful because it provides the foundations of new museums.

The Metropolitan’s proposed expansion plan invades much needed Park land; it is hardly reassuring to have the Museum argue that it will be returning park land to public use by making use of space now occupied by a parking lot. In 1876 a city charter granted the Museum legal occupancy of an area of the Park bounded on the east and the west by Fifth Avenue and the East Drive in the Park, and on the north and south by 85th Street and 80th Street. But in 1876 the ratio of citizens to available Park land was considerably lower than it is today. The charter is outdated, outmoded, and no longer valid.

To pacify Park lovers it has been pointed out that the new structure will include two glass-enclosed garden courts attractively labeled “New year-round public gardens.” Their public availability, however, is restricted by Museum hours and Museum rules, not to mention the impossible crowding at peak hours.

The Museum has given no binding assurance about further expansion plans. To calm our fears Museum spokesmen have variously promised that it will undertake no further collecting or that it will collect only news-worthy items or architectural sculptures. Yet they have at the same time requested additional funds for new acquisitions and have failed to state that they will adopt a policy of refusing large donations, especially those conditional on the construction of new wings.

Lewis Mumford has called the expansion plan “another nail in New York’s coffin.” Many other citizens concerned with conservation, pollution, and urban planning oppose the present plan and the many changes it will make in the environment of the Park. They feel that a thorough study of these problems should be made available to the public before any final decision is reached. Their request has been ignored. Two adjacent community planning boards are opposed to the present expansion plan. The Museum has failed to respond to any of them and in fact chose not to consult any community planning board when the plan was drawn up.

Since the Museum is requesting and receiving money from the city for maintenance and expansion, why has this not been publicly brought before the Board of Estimate? The city has just allocated $9.7 million from its capital budget for work on roofs, skylights, and “other alterations.” By what skillful wording of its requests has the Museum avoided the public hearings usually conducted by the Board of Estimate when expenditures of this size are in question? The Museum is now asking for additional city funds, including $125,000 for planning the future American and European wings. It has been repeatedly stated that the funds for the proposed expansion plan will come from private sources. Therefore, why is the Museum requesting money from the city at the expense of other community cultural centers in need of support?

It will be irresponsible if the proposed expansion is carried out before full consideration has been given to the many questions raised by the Museum’s plan. It is the duty of those in public office to see that this is done.

Gabriella B. Canfield

New York Museum Action

Antonio Olivieri, Cochairman

112 East 74th Street

New York, New York 10021

988-2748

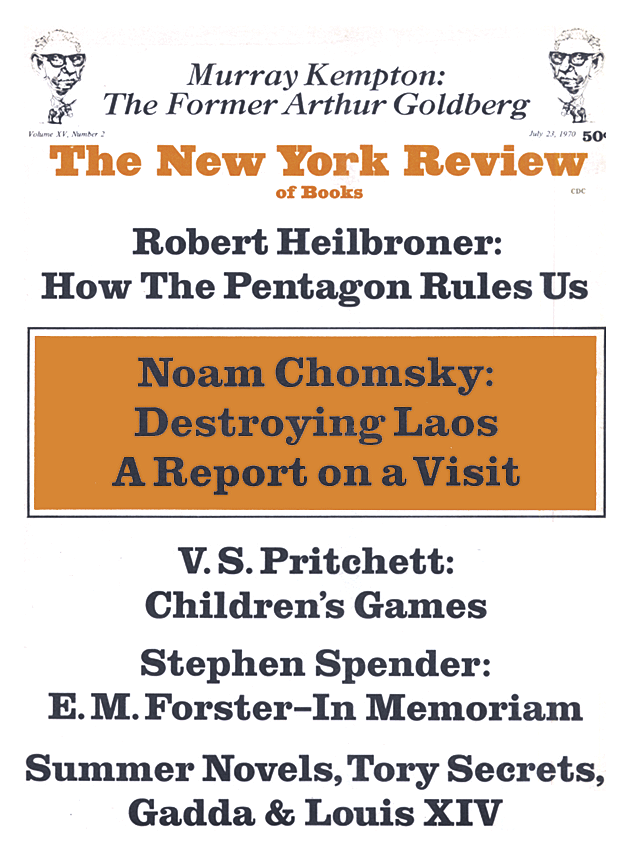

This Issue

July 23, 1970