To the Editors:

In a story in the July 3 New York Times I read, “According to the best estimates, from 5 to 20 percent of American children suffer from…a complex and little-understood learning and behavior disorder sometimes called ‘minimal brain dysfunction’…such children, usually boys, are all too evident in almost every classroom. They jump up and down, throw paper airplanes at the teacher, fight and shove on the lunch line, can concentrate for only a short time, frustrate easily, etc. etc.” I then read that many doctors are treating this so-called disorder by dosing the children with amphetamines.

It is most unfortunate that the Times should have given this much support to this currently fashionable quackery, which blames on the nervous systems of children the stupidities and inhumanities of our schools, recently described by Charles Silberman in detail in an all too aptly titled article, “Murder in the Schoolroom.”

We take lively, curious, energetic children, eager to make contact with the world and to learn about it, stick them in barren classrooms with teachers who on the whole neither like nor respect nor understand nor trust them, restrict their freedom of speech and movement to a degree that would be judged excessive and inhuman even in a maximum security prison, and that their teachers themselves could not and would not tolerate. Then, when the children resist this brutalizing and stupefying treatment and retreat from it in anger, bewilderment, and terror, we say that they are sick with “complex and little-understood” disorders, and proceed to dose them with powerful drugs that are indeed complex and of whose long-run effects we know little or nothing, so that they may be more ready to do the asinine things the schools ask them to do.

It would seem reasonable and prudent, to say nothing of scientific, to ask ourselves a few questions about this “complex and little-understood disorder” that supposedly afflicts as many as 20 percent of our children. If indeed it has something to do with injuries incurred during or soon after birth, how is it possible that it affects mostly boys? Is it not a hundred times more likely that boys have a harder time in school because their women teachers do not like and cannot deal with the kind of behavior that boys have grown up to think of as being appropriately boyish? Might it not be wise to see whether there is as great an incidence of this “disorder” in classes that are taught by men, or in schools where the children are not forbidden to move or talk? Might it not also be wise to see whether there is some correlation between the incidence of this disorder and the age of the teacher, or the rigidity of the classroom? If this is indeed a defect induced at birth, births being about the same everywhere, might it not be wise to inquire whether other countries have also noticed this strange “disorder”? Given the fact that some children are more energetic and active than others, might it not be easier, more healthy, and more humane to deal with this fact by giving them more time and scope to make use of and work off their energy?

It is not surprising that the schools in many places should have given their support to this practice of doping children to make them quiet and docile in school, but that so many doctors and psychiatrists have joined them in doing so seems to me shocking and disgusting beyond words. And finally we must ask ourselves what can be the effect on a child of being told that he is so incurably bad that only a powerful pill can make him good?

Someone may suggest soon that the easiest and surest way to solve the problems of our schools may be to give all children a pre-frontal lobotomy at birth, or plant some behavior-controlling electrodes in their heads. We seem to me to be dangerously close to such horrors.

John Holt

Boston, Massachusetts

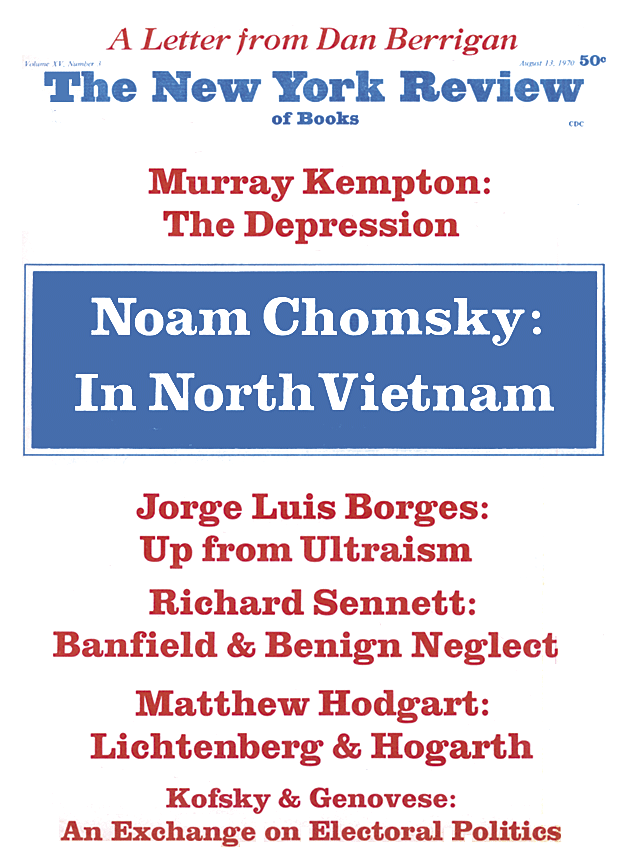

This Issue

August 13, 1970