How can a contemporary novelist confront experience? How, knowing that art has worn out so many of the details of life, can one still fix a narrative of a novel’s length into a world made up of “things” and “characters”? How can one make the selection of events or the color of an eye without arousing disquieting feelings about old-fashioned literary calculation? Or again, how to make those eyes and the events they witness not seem examples of a self-indulgent modernism or a coy eccentricity? When excess is tolerated, indeed sought after, by the public and its critics, how can one keep those first tentative ideas for a novel from serving an easy, étonne-moi aesthetic?

Finally, how simply to describe, how to hang qualifiers, metaphors, and images onto events without making the language seem obstructive or cloying, without bringing on oneself the charge of naïveté, of writing as if the objects of the world had not already been heavily described by those masters who made the novel an exploration in naming the particulars of experience? More primitive still: How to move a character across a furniture-stuffed room and not create the deadening sense that words once again are bustling us through a moment that seems somehow perfunctory and that writer and reader are being held by an effete convention?

These questions nowadays hover around the novel. One does not need to believe in a non-linear theory of art, or in progress, or in the artist as a conquistador of new forms, to wonder if this ritual exchange between a single imagination and a loose gathering of receptive readers has not become an empty, formal agreement—a matter of cultural manners rather than a spontaneous and enjoyable common trust. Fortunately, of course, these questions do not intrude each time someone with a literate memory reads, or for that matter writes, the first sentence of a novel. Just as we do not inhibit our daily actions by constantly justifying them with ethical principles, so also we do not read for pleasure only after assuring ourselves that the novel, as an expressive form in the last third of the twentieth century, still vindicates itself. Nevertheless, there are moments—at a sudden break in the narrative, for instance, when we see a cloudburst of fine writing coming on; or when punctuation begins to fade, words couple with their neighbors, and we know that we are off into another neatly planned simulation of unguarded thought—when all the paraphernalia of the novel seem like polite rituals.

If the novels of John Updike occasion such speculations, it is because they are more nakedly traditional than the works of most of our readable contemporaries. By traditional I do not mean that they are simply put together with a debt to a certain historical style, but rather that they present fragments of life without the constant imposition of extraneous attitude, without, that is to say, making the self-conscious and fashionable gestures to irony. The Centaur, Rabbit, Run, Of the Farm, Couples are all works that unfold stories which seem to have no large aesthetic or philosophical frame from which the reader is meant to derive their meaning. Here and there, one may sniff out in these novels some genteel religiosity or notion of a guiltless nature that is a witness to, and absorbant of, human passion; but most of the incidents unfold in Updike’s work without metaphysical coercion or formalist tricks.*

Then, too, to narrow the idea of tradition, Updike’s works have generally come to us without the fashionable patina of creative self-consciousness. They do not writhe over the problem of their own composition; in their margins there is no apperceptive author whispering dicta on what fiction can and cannot do. In a time of antinovels, epistemological novels, novels as reportage, novels as history, novels as games, etc., Updike accepts the old principles of the form. He does not torture, analyze, or make fun of the novel so that it will not seem a quaint and out-of-date curio. From this assurance comes, I assume, his belief in the novel of characters and his narrator’s trust in their plain predicaments.

Here, of course, he is heir to a specific Anglo-American legacy; namely, that the writer is esteemed not for his powers to fabricate examples of the outlandish, but rather for his ability to uncover unusual patterns and shadings where an ungifted eye sees only a single, quotidian tone. Often this means that he must examine with exhausting effort the unassuming and commonplace so that he can make the truths about them self-evident and impressive. To do this today argues great faith in the slow, hard-won revelations of novels and in the absolute value of imaginary men and women whose claim to our attention is predicated on the value of their author’s insights and on how smoothly he forces us to make the transition from his tidy world of language to our rough, disordered one of experience.

Advertisement

To read Updike, then, is to come to the heart of a form that has seen a lot of hard service in the past. Rabbit, Run and The Centaur, to me his most successful works, do not try to disguise their heritage. Indeed, they insist upon it. At every page they reveal themselves as artifices, as written, as a display of observation. The celebrated Updike style, that often wearisome struggle for the most precise yet extensive metaphor, is like those Dickensian asides that unabashedly remind us that a writer is present. This reminder, however, is not meant to unsettle our belief in the experience of fiction. On the contrary, it is rather an attempt to re-enforce it, to make certain that the reader attains a certain emotional intensity, that he will see and feel as the author wants him to.

Sometimes, as when Rabbit takes flight at the beginning of his story, there is a tense balance kept between the packed, unremitting lyricism of Updike’s prose and the action it surrounds; from image to image, one can almost catch the language breathing in rapid unison with Rabbit. The details of the impromptu basketball court, the apartment, the town, and the labyrinthian turnpike at night are described in a way that suggests that they are charged with secrets vital to Rabbit’s life, secrets that might be uncovered if analogies were pushed further and further to the resolution of a final metaphor. Rabbit’s spasmic escape sustains all this in the way that the leisurely scope of the Victorian novel permitted an author time to sigh and moralize in his own voice without breaking the rhythms of his art and causing the reader to stumble out of a psychic sympathy with him.

Similarly, in The Centaur, Caldwell, a teacher moving half gratefully toward death after a lifetime of trying to kindle in his students an interest in the universe, is caught at such a heightened point in his life and in such extremes of self-abnegation that one appreciates Updike’s intention to hold him firmly within the finely described details of a small town, to fix him, as it were, on a proper level of reality.

Caldwell is an eccentrically powerful character, and it is interesting to see Updike work so hard, not only to surround his protagonist with mystery, but also to ensure that this high-school teacher will not carry a meaning beyond himself. Whereas in Rabbit, Run, the “writing” is meant to approximate the inarticulate awareness that is driving Rabbit, in The Centaur it serves the opposite purpose; to counteract ironically Caldwell’s slightly mysterious, evocative behavior. Even in this ambitious book, Updike wants to stay within the boundaries of the traditional novel, to convince us of the common actuality of what is presented.

Sometimes, however, as in Couples, Updike merely convinces us that his lyrical moments are little more than escapes from the novel itself. In such a work, one sees why there exists a certain impatience with the old assumptions of the novel. For Couples is almost a case study in the effects of literary decadence, if such a phrase is taken to mean purposeless ornamentation, formalized passions, and a joyless candor about sex that tries to disguise the lack of any real life in all those swooning copulations.

For all his gifts and intelligence, Updike seems as lost as the reader in this saga of suburban Angst. Here all his traditional weapons have let him down: he has observed keenly, each of his characters carries his own portmanteau of telling peculiarities, events glide together neatly and engender enough agitation to keep the couples of Tarbox moving through their abortions, wife-swappings, community intrigues, and graceless aging. Yet everything seems frozen and all of Updike’s ingenious evocations of seascapes or prose illuminations of the orgasm cannot animate a book that is so formally dead.

It would be simple to say that Couples is merely a stillborn effort, a good writer’s failure. However, I think that there is something more portentous in this collapse, something that almost suggests the exhaustion of the genre itself. For it is not so much that this novel is bad as that it is worn out. Reading it, one feels more and more constricted by the limits Updike has set. When a good writer makes all the right choices and still comes up with a four-hundred-page stretch of tedium artificially stimulated by an occasional, anxious lyricism, one may very well wonder if some mistake has not been made that runs far deeper than miscalculation. One could conclude that the form itself no longer sustains our interest and that, like the modes of allegory, it has had its time.

Advertisement

From this dark hypothesis it is easy to come to Updike’s most recent work, Bech: A Book, for of all the many things Bech is, he is mainly a beguiling embodiment of the novelist’s problem. Bech is a blocked writer. The author of a reputation-making first novel, a reputation-bolstering novella, and a long “noble failure,” Bech has, in his middle forties, fallen on barren times. He now writes, we are told, a review or two and some “subjective reportage” for Esquire. Apart from these, his muse is silent and he is gradually fading into a literary “personality,” an object to be dispatched on cultural exchanges and lecture tours.

He is indeed a harried man, and we see him at cross monologues with his Iron Curtain colleagues, being used for a week by a pretty gossip columnist in London, fighting the tedium of his mistress and the vacuities of a former student while vacationing at a place resembling Martha’s Vineyard, and sensing death and the breakdown of his art while on the fecund campus of a Southern college for girls. Throughout, Bech keeps a keen, melancholy, and ironic eye on his absurdities, and gradually becomes that rarity in modern fiction: a real portrait of a writer that is appositely agonizing and justifiably humorous.

In the book’s Foreword, a benediction from Bech himself, Updike has anticipated the roman à clef games by admitting that Bech is something of a Jewish pastiche. To me, because his musings are so Herzogian, there is more Bellow in Bech than Mailer, Roth, Malamud, et al., but this is only a dutiful conjecture. Bech is a way of literary life that has in part absorbed many writers, a way of life that presents slightly tawdry but comforting alternatives to the work they feel guilty for not doing. But it is really not Bech’s career that interests or the fact that, as he says, he has become his own creation. Rather, it is his darker battle to hold onto his faith in art itself that keeps Bech from being simply a clever conceit. The battle is fought on all levels: from the vapidness and willful misunderstanding of an interviewer to Bech’s own disquieting night thoughts. But his worst moments come when he is surrounded by intensely literary Southern belles at a dinner table. First, they give him a classic case of existential upset:

Their massed fertility was overwhelming: their bodies were being broadened and readied to generate from their own cells a new body to be pushed from the old, and in time to push bodies from itself, and so on into eternity, an ocean of doubling and redoubling cells within which his own conscious moment was soon to wink out. He had had no child. He had spilled his seed upon the ground. Yet we are all seed spilled upon the ground. These thoughts, as Valéry had predicted, did not come neatly, in chiming packets of language, but as slithering, overlapping sensations, microorganisms of thoughts setting up in sum a panicked sweat on Bech’s palms and a palpable nausea behind his belt.

And the defense and consolation of art?

He looked around the ring of munching females and saw their bodies as a Martian or a mollusc might see them, as pulpy stalks of bundled nerves oddly pinched to a bud of concentration in the head, a hairy bone nob holding some pounds of jelly in which a trillion circuits, mostly dead, kept records, coded motor operations, and generated an excess of electricity that pressed into the hairless side of the head and leaked through the orifices, in the form of pained, hopeful noises and a simian dance of wrinkles. Impossible mirage! A blot on nothingness. And to think that all the efforts of his life—his preening, his lovemaking, his typing—boiled down to the attempt to displace a few sparks, to bias a few circuits, within some random other scoops of jelly that would, in less time than it takes the Andreas Fault to shrug or the tail-tip of Scorpio to crawl an inch across the map of Heaven, be utterly dissolved. The widest fame and most enduring excellence shrank to nothing in this perspective.

Have such thoughts stultified Bech, or has his block created convenient, apocalyptic visions of human insignificance? It really doesn’t matter, for Bech loses either way. Pinioned by his own fears, trapped, as he again tells us, in a naturalistic style, there is nothing left for him but to accept the honors of his society as though they were post-mortem testaments.

Updike could have had many intentions in writing Bech: as a rejoinder to a competing style, as a parody of fashionable attitudes, as a sympathetic act of imagination, as an attempt to state the American writer’s case in the broadest terms possible. However, whatever the impetus, he has written a book quite unlike any of his previous works, a book that does not seem to struggle with the obligations of convention, that does not have to wrest its excellence from eroded soil. Everything about Bech is lean, antic, and to the point, and it has a daring that is supported, rather than encumbered, by the lessons of tradition. With its intelligence and verve, Bech reaffirms that writing is still our most subtle way of telling things. Perhaps also it hints that, in finally stultifying Bech, Updike has propitiously somewhat liberated himself.

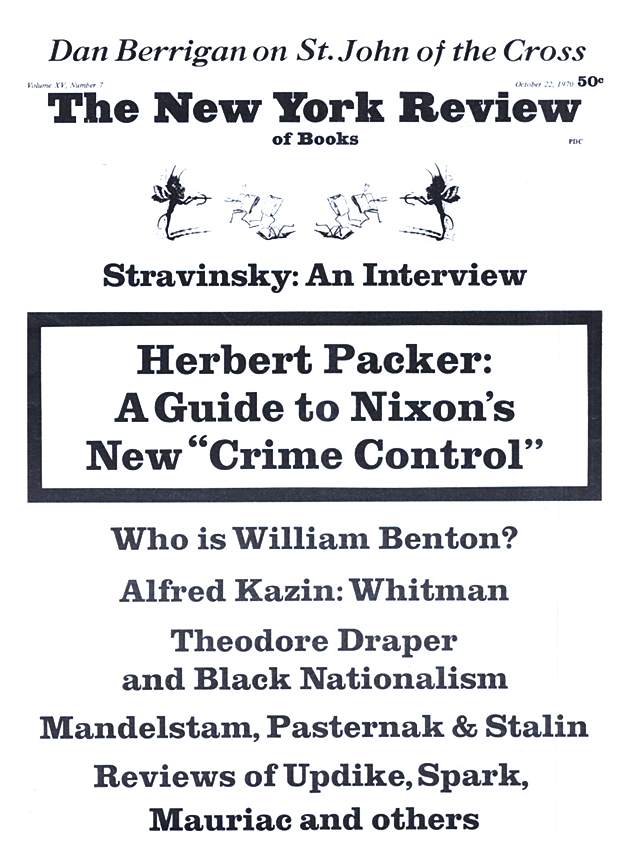

This Issue

October 22, 1970

-

*

The one exception to Updike’s general lack of literary guile is, of course, the mythological overlay of The Centaur. Those Greek intrusions into the Americana of a small-town high school seem so mistaken and so at variance with the usual fine integration of his novels, that, in speaking generally of his work, I would prefer to set them aside as a collective instance of simple absence of mind. ↩