The pseudo-private corporations of the United States and the pseudo-public firms of the USSR have this much in common: neither comes close to achieving “industrial democracy.” As an organizing principle, hierarchy seems to have won out over democratic participation.

Probably the most radical alternative to the American and Soviet methods of governing economic enterprises is the system of self-management that has been developed in Yugoslavia since 1950. Yugoslavia is the only country in the world where a serious effort has been made to translate the old dream of industrial democracy into reality—or into as much reality as dreams usually are. Let me add at once that in the government of its state apparatus, Yugoslavia is not, of course, a representative democracy. The leadership has not yet permitted an opposition party to exist; as the famous cases of Djilas and Mihajlov show, merely to advocate an opposition party may land one in jail. Yet if Yugoslavia is less democratic than the United States in the government of the state, it is more democratic in the way industries and other enterprises are governed. In both respects, of course, it is much more democratic than the USSR.

In fact, it was after Yugoslavia broke out of the Soviet orbit that her leaders introduced social self-management1 as a deliberate and systematic effort to shift from the orthodox, highly centralized, bureaucratic Soviet-style socialism toward a socialism that would be more democratic, liberal, humane, and decentralized. During their brief revolution in 1968, the Czechs also moved rapidly toward decentralized socialism. Beginning in June, 1968, elected councils were established within a few months in several hundred firms, including the Skoda works in Pilsen, the largest in Czechoslovakia. But after the Russians moved in, this dangerous challenge to bureaucratic socialism was suppressed and the radical idea of self-management was attacked as anti-socialist; the only appropriate representative of the workers was, naturally, the party.

Although in Yugoslavia the most dramatic step toward industrial democracy and the one most relevant here was the introduction of workers’ councils throughout all economic enterprises,2 the principle of social self-management was gradually extended to include practically every kind of organized unit—local governments, rural coops, schools, hospitals, apartment houses, the post office, telephone services.3

It would be a gross exaggeration to say that self-management of economic enterprises in Yugoslavia is a complete or wholly satisfactory achievement of industrial democracy. But, in conjunction with other aspects of the Yugoslav system, about which I shall have a word to say in a moment, the workers’ councils seem to have produced not only a relatively decentralized economy but a substantial amount of participation by workers in the government of industry and of work generally. To be sure, the workers’ councils are by no means autonomous; here as elsewhere in Yugoslavia organized party opposition is not permitted; strikes are rare and of doubtful legality; and the special influence of the party is important. Nonetheless, it seems clear that the councils elected by the workers are very much more than a façade behind which the party and state officials actually manage an enterprise.

What happens to “property rights” in such a system? Who owns the factory, railroad, bank, retail firm? In this kind of system the great myth of the nineteenth century stands exposed; ownership is dissolved into its various components. What is left? A kind of ghostly penumbra around the enterprise. The enterprise is described in the constitution as “social property.” But it might be closer to the mark to say that no one owns it. It is not, certainly, owned by the state or by shareholders. It is not owned by the workers. The point is that “property” is a bundle of rights. Once the pieces in this bundle have been parceled out, nothing exactly corresponding to the conventional meaning of ownership or property remains.

How competently would the employees of large firms in the United States manage their enterprises under such a system? Would American enterprises be as efficiently run as at present? One ought to keep in mind that even a modest decline in physical productivity could be offset by some important gains, of which the most significant would be to transform employees from corporate subjects to citizens of the enterprise. How great a gain this would be depends on how much value we (and the employees) attach to democratic participation and control, as good both intrinsically and in their consequences for self-development and human satisfaction, quite independently of other goals.

In the absence of strictly relevant experience, predictions about productivity are of course hazardous. Although one can hardly compare Yugoslavia and the United States on this matter, it is significant that the introduction of self-management in Yugoslavia was followed by a rapid rise in productivity. As to the consequences for productivity of the various less radical schemes of employee participation and consultation that have been tried out in this country and elsewhere, the evidence is inconclusive.4

Advertisement

But surely the most relevant consideration is that in the United States management is increasingly professional and therefore available for hire. In fact, the emerging practice in the American corporation is for managers and even management teams to shift about among firms. In a recent book on the American corporation, Richard Barber writes:

…the old notion that a responsible official stays with his company, rising through the ranks and wearing the indelible badge of Ford or IBM or duPont, is quaint and out of tune with a world of skilled scientific business management. It is not that the new executive is any less interested in or dedicated to the success of the company that employs him; rather it is that he sees himself as a specialist whose skills and growth are in no way necessarily associated with any particular enterprise.5

I do not see why a board of directors elected by the employees could not select managers as competent as those selected by a board of directors chosen by banks, insurance companies, or the managers themselves. The board of a self-governing firm might hire a management team on a term contract in the way that a board of directors of a mutual fund often does now—and also fire them if they are incompetent. If the “profit motive” is all that it has been touted to be, who would have more at stake in improving the earnings of a firm than employees, if the management were responsible to them rather than to stockholders?

Moreover, the development of professional managers sharply spotlights the old question, Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? As Barber points out:

With corporate managers holding the reins of widely diversified, global firms, but conceiving of themselves essentially as professionals, what are the rules—the standards—with which these men are to be governed in their use of the immense power they possess? As well, how are those within the corporation—especially its multitudinous family of technocrats and middle-level executives—to be protected from encroachment on their legitimate interests?6

Although Barber poses the question, he offers no answer. Yet self-management is one solution too obvious to be ignored—except in a country blinded by an unthinking adherence to the absolute conception of a “private” firm “owned” by stockholders.

It is not, I think, the question of competence that raises problems for the introduction of self-management in American firms, but the possibility that on the one hand many employees of a particular firm might not wish to participate in governing it, while on the other hand many people outside the firm might not only want to participate but could make a very good case for their right to do so.

Consider the people who work in an enterprise. While many employees, particularly technicians and lower executives, would probably welcome self-management, it is very much open to doubt, unfortunately, whether blue-collar workers want to allocate any of their attention, time, and energy to governing the enterprises in which they work. Although sentimentalists on the left may find the idea too repugnant to stomach, workers and trade unions may be the greatest barriers at present to any profound reconstruction of economic enterprise in this country. Several aspects of their outlook militate against basic changes. Along with the officialdom of the trade union movement, workers are deeply ingrained with the old private property view of economic enterprise. What is perhaps more important, affluent American workers, like affluent workers in many other advanced countries and the middle class everywhere, tend to be consumption-oriented, acquisitive, privatistic, and family-centered. This orientation has little place for a passionate aspiration toward effective citizenship in the enterprise (or perhaps even in the state!). The job is viewed as an activity not intrinsically gratifying or worthwhile but rather as an instrument for gaining money which the worker and his family can spend on articles of consumption.

In so far as this is true, the modern worker has become what classical economists said he was: an economic man compelled to perform intrinsically unrewarding, unpleasant, and even hateful labor in order to gain money to live on. So far as its intrinsic rewards are concerned, work is simply so much time lost out of one’s life. The work place, then, is not a small society; it is simply a place where you put in time and labor in order to earn money.7 The union is a necessary instrument, but it is also a crashing bore. Solidarity is a matter of sticking together during bargaining and strikes in order to get better wages and working conditions, but it is not animated by any desire to change the structure of power within the firm.

Advertisement

The result for many workers is that a chance to participate in the government of a factory or business (even during working hours) might very well hold slight attraction. We know, after all, that in every representative government in the world, and even in the more direct democracy of many New England towns, including my own, a great many citizens are indifferent toward their opportunities to participate. How much more true this is likely to be in the business firm: so long as the enterprise pays good wages, its affairs seem even less interesting than affairs of state. In addition to reflecting these attitudes of their constituents, trade union leaders could easily interpret self-management as a threat to their influence: the consequences for incumbent leaders would at best be uncertain, and like leaders generally, most trade union leaders prefer to avoid risks.

Yet these bleak prospects are by no means the whole story. The impetus toward self-management may not come from the strata which the conventional left (old and new) has for so long courted with such meager response. It may come instead from the white-collar employees, technicians, and the executives themselves. What is more, there is a good deal of evidence to show that although participation may not guarantee increased output in the conventional sense, it does generally increase the worker’s satisfaction with and interest in his work. If a significant number of employees, whether white-collar or blue-collar, were to discover that participation in the affairs of their factory or firm—or that part most directly important to them—contributed to their own sense of competence and helped them to control an important part of their daily lives, then lassitude and indifference toward participation might change into interest and concern. Of course, we should not expect too much. But we should also not reject self-management because it may not measure up to the highest ideals of participation—ideals that are, after all, not met in any democratic association.

The most severe problem raised by self-management is, I believe, the existence of interests other than the employees of an enterprise: not only consumers but others who may be affected by decisions about location, employment, discrimination, innovation, safety, pollution, and so on. Decisions made in the automobile industry, for example, have obvious consequences for a great many persons outside the industry. Car buyers are affected by poor safety features and by planned obsolescence. Unless the industry can be induced to develop and adopt exhaust control devices, nearly all of us stand a good chance of suffering harm sooner or later.

How can these and other affected interests be sure that their claims will be fairly weighed in the decisions of the firm? By focusing attention on the state as the best agent of all such affected interests, this question often drives the advocate of change straight onto the horns of the old dilemma: either bureaucratic socialism or else the private property solution. Is the only alternative to the giant American corporation the highly centralized, bureaucratically run enterprise that, however much the dead weight of hierarchy violates socialism in theory, is the usual outcome of socialization in practice? It is precisely because it enables us to escape this dilemma that self-management is so hopeful an alternative. Have we then escaped the dilemma only to find it lying in wait farther down the road?

I shall not pause to argue with any reader, if there be one, who is so unworldly as to suppose that once “the workers” control an enterprise they will spontaneously act “in the interests of all.” Let me simply remind this hypothetical and I hope nonexistent reader that if self-management were introduced today, tomorrow’s citizens in the enterprise would be yesterday’s employees. Is their moral redemption and purification so near at hand? If not, must self-management wait until workers are more virtuous than human beings have ever been heretofore? For my part it seems wiser to arrange the structure of government on the assumption that people will not always be virtuous and at times surely will be tempted to do evil, yet in a way that will produce the incentive and the opportunities to act according to their highest potential.

If we keep in mind that internal controls over the decisions of a firm can be supplemented by controls from outside, whether by the government of the state or by other economic entities, we will easily see that various affected interests might be protected in roughly three ways that are not mutually exclusive.

To begin with, in addition to workers, others whose interests would be affected by the decisions of an enterprise might be given the right to participate in decisions—to have a direct say in management, for example, through representatives on the board of directors of the firm. Thus the board of directors might consist of one-third representatives elected by employees, one-third consumer representatives, and one-third delegates of federal, state, and local governments. A system of this kind might be called interest group management.

Now candor compels me to admit that interest group management seems much more in the American grain than self-management. It fits the American ethos and political culture, I think, to suppose that conflicting interests can and should be made to negotiate: therefore let all the parties at interest sit on the board of directors. It would be a very American thing to do. Interest group management is, then, a development much more likely than self-management. It is hard for me to see how American corporations can indefinitely fight off proposals like those most recently made by Ralph Nader for consumer or public members on their boards.

I can readily see how we may arrive incrementally at interest group management of giant firms. One of these days a group of stockholders may succeed in electing several consumers’ representatives to a board of directors. Some trade union leaders might be co-opted. A federal law might compel boards to accept a few public representatives. In time, a reform-minded national administration might even push a law through Congress providing in some detail for representation of employees, consumers, and the general public on the boards of all firms over some minimum size. Since this innovation would probably be enough to deflate weak pressures for further change, the idea of self-management would be moribund.

Yet even if interest group management is more likely, it is much less desirable, in my view, than self-management. For one thing, interest group management does very little to democratize the internal environment of an enterprise. Instead, it would convert the firm into a system of rather remote delegated authority. For there is no democratic unit within which consumer representatives, for example, could be elected and held accountable. The delegates of the affected interests doubtless would all have to be appointed in one way or another by the federal government, by organized interest groups, by professional associations. There would be the ticklish problem of what interests were to be represented and in what proportions—a problem the Guild Socialists struggled with, but never, I think, solved satisfactorily.

Since the consequences of different decisions affect different interests, have different weights, and cannot always be anticipated, what particular interests are to be on the board of management, and how are they to be chosen? Are the employees to elect a majority or only a minority? If their representatives are a majority, the representatives of other affected interests will hardly be more than an advisory council. If a minority, I fear that most people who work for large enterprises would be pretty much where they are now, remote from the responsibility for decisions.

Doubtless interest group management would be an improvement over the present arrangements, and it may be what Americans will be content with, if the corporation is to be reformed at all. Yet it is a long way from the sort of structural change that would help to reduce the powerlessness of the ordinary American employee.

Moreover, interest group management would not eliminate the need for economic and governmental controls. For example, it would be madness in any economy to allow a firm unlimited power over the price of its product or unlimited access to funds for investment. Internal decisions on such matters may be influenced by market forces, by bargaining, by a regulatory agency, or by other means; but they cannot be left wholly within the discretion of the particular enterprise. Is it not through these external controls, rather than through participation in the internal control of the firm, that the affected interests could best be represented and protected in a system of self-management?

I cannot stress too strongly the importance of external controls, both governmental and economic. I do not see how economic enterprises can be operated satisfactorily in a modern economy, capitalist, mixed, socialist, or whatever, without some strategic external controls over the firm and its profits. However much the Yugoslavs recoil from the Soviet example of bureaucratic socialism, on this point they have no doubts. Their external controls include the forces of the market and credit, norms for salaries and the allocation of revenues, and the ubiquitous presence of the well-disciplined League of Communists. A firm is forbidden by law from selling off its assets for the benefit of the employees. The central government sets minimum wage levels; local governments may increase these levels. Depreciation rates are regulated. Foreign exchange restrictions are severe.

It is worth keeping in mind, too, that the less effective the external economic controls are—the influences of the customers and suppliers on costs and prices, of suppliers of capital and credit on interest rates and terms of borrowing, of competing firms and products on the growth and prosperity of other firms—the greater must be the governmental controls. Just as the extreme limit of economic controls is the fully competitive economy (whether capitalist or socialist), so the extreme limit of governmental controls is bureaucratic socialism. The optimum combination of internal, governmental, and economic controls will not be easy to find.

Yet it seems obvious that if we place much value on democracy at the work place, our present arrangement is ludicrously far from desirable. As for alternatives, only self-management can provide anything approaching genuine democratic authority in the American business firm. Neither the present system, nor bureaucratic socialism, nor even interest group management, holds out much real hope of reconciling the imperatives of economic organization with democratic authority.

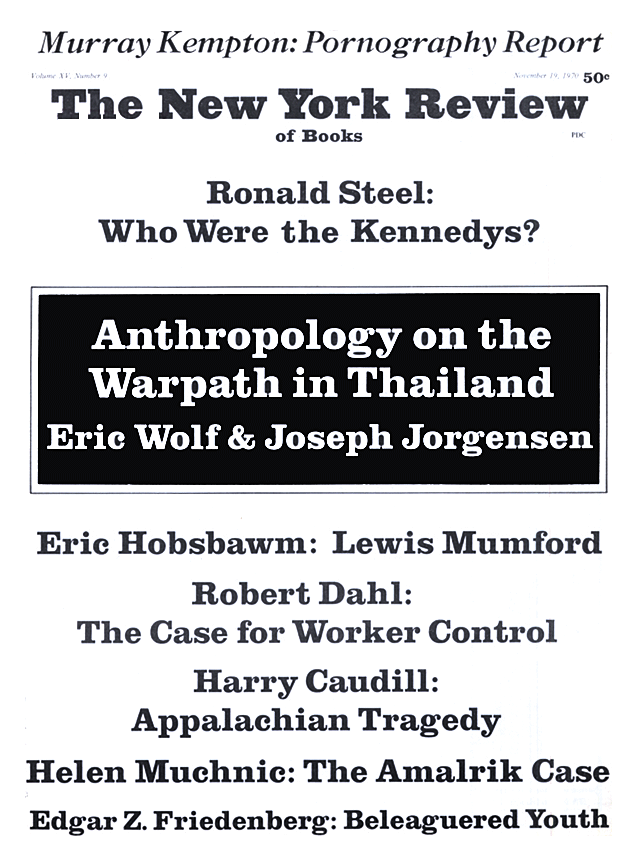

This Issue

November 19, 1970

-

1

“Social self-management” is the English translation of the Serbo-Croatian term used to cover the various forms of participatory authority at the lower levels. Thus the workers’ councils are said to represent workers’ self-management; at the municipal level (the commune) the term self-government is often used. See, e. g., Constitution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Ch. II, Art. 6, and Ch. V, Art. 96. ↩

-

2

Every person working in an enterprise is entitled to participate in the choice of the workers’ council. In an enterprise with fewer than thirty people, the council consists of everyone in the enterprise except the director; in firms with more than seventy people, they must elect a council; in firms with between thirty and seventy persons they opt for one solution or the other. ↩

-

3

Readers looking for information about Yugoslavia’s experience with self-management will find a brief, objective account (together with short descriptions of efforts toward industrial democracy in Sweden and the abortive movement in Czechoslovakia in 1968) in agenour (Brussels, November, 1969), pp. 28-40. Jiri Kolaja’s Workers’ Councils: The Yugoslav Experience (Praeger, 1966) is short and seemingly reliable, though somewhat out of date. ↩

-

4

See, for example, Rhenman, Industrial Democracy and Industrial Management, pp. 83-84. ↩

-

5

The American Corporation: Its Power, Its Money, Its Politics (Dutton, 1970), p. 97. ↩

-

6

Ibid., p. 98. ↩

-

7

The best evidence on this point that I am aware of comes from a study of attitudes of affluent workers in Britain, not the United States. See the three volumes of The Affluent Worker, edited by John H. Goldthorpe, David Lockwood, Frank Bechofer, and Jennifer Platt (Cambridge: At the University Press, 1968-69), Vol. 1, Industrial Attitudes and Behavior; Vol. 2, Political Attitudes and Behavior; Vol. 3, In the Class Structure. See especially Vol. 3, ch. 3, “The World of Work.” ↩