In response to:

Divided Selves from the October 22, 1970 issue

To the Editors:

Because of the immunity that critics enjoy, it is considered unseemly to answer back, even to defend a book which has been reviewed irresponsibly, in a way unworthy of the book, the readers of The New York Review, and the reviewer. The defender runs the risk (since the critic is presumed to be right) of doing further damage to the book and of reawakening the pleasurable pity that the zapping of the book evoked in the first place in the hearts of those who had not read it. However, I am running the risk and hope at least to make the point that a critic has the duty to read a book with attention before he reviews it. Mr. D.A.N. Jones, who reviews The Manuscripts of Pauline Archange by Marie-Claire Blais in your October 22 issue, did not read it with attention, has reduced it to the dimensions of his own irritability and prejudices, and by the use of generalizations and fabrications that throw more light on him than they do on the book, has destroyed it for New York Review readers.

From the beginning, Mr. Jones is irritated by Miss Blais’s long sentences, which “unroll…like parodies of Proust.” Are long sentences the exclusive property of Proust? Are short sentences the exclusive property of Hemingway or Isaac Singer? Miss Blais writes short sentences, too, and perhaps should be criticized for that—as at the end of Chapter III of the book, “September was approaching. My big suitcase lay in the shadows, packed with black things, like my past.” Her sentences belong to no one except herself. But just as Mr. Jones implies that the book is only composed of long sentences, he implies that violence is its only subject matter. “In this Canadian town,” he says,

torture is the main preoccupation: cats are skinned alive and children beaten [read “cat” for “cats” and “child” for “children”] until their eyes bleed. Meanwhile, a Genetesque priest makes love to a boy murderer with a vague, cruel smile.

Mr. Jones’s “meanwhile” suggests that all these events have taken place simultaneously, though they are in fact spread over the 213 pages of the book. Worse still, he has not read the book carefully enough to realize that the priest had nothing in common with Genet and that he does not make love to the murderer but is only supposed to have done so by a character (Germaine Léonard) who is as squeamish as Mr. Jones. Mr. Jones has not noticed either that the book contains pages of the purest humor—the parts about Julien Laforêt and Romaine Petit-Page and the pages near the end about the Bellemort family.

One comes to the end of the review with a sense of incredulity. “Its sensuous appreciation of pain, cruelty, and guilt,” says Mr. Jones, “is so unrestrained as to be finally ludicrous.” Is it really possible to misread the book in this way, can Mr. Jones really not see that Pauline, who admittedly suffers from guilt, suffers equally from her experience of pain and cruelty? Can this attempt to exorcise pain by writing about it, by making it into the material of a writer’s life be called “sensuous appreciation” or is Miss Blais’s crime to have written too well about things that Mr. Jones prefers not to think about?

Mary Meigs

Wellfleet, Massachusetts

D.A.N Jones replies:

If Miss Blais is trying to “exorcize pain” (out, demons, out?) I wish her good luck. But how does Miss Meigs know this? Any more than she knows that I am irritable, prejudiced, and squeamish? It is better to discuss the text of a book (or review) than to attempt a long-distance analysis of the writer’s character.

It seems oversubtle to charge me with “squeamishness” when I have admitted to finding Miss Blais’s horror stories “ludicrous.” My fault would seem to be insensitivity, rather than oversensitivity. But I did not laugh at the atrocious deeds recounted in the four other novels I reviewed. Perhaps Miss Blais’s novel piled on the agony to the point (well-known to producers of Titus Andronicus, makers of horror stories, and comic-song writers) where audiences start to laugh, D. A. N. Jones among them. This would seem to be the only “light thrown” on me by my review.

Is the priest Genetesque? If Miss Meigs will compare his dialogue with Genet’s Journal du Voleur, she will recognize the similarities. Does he “make love” to the murderer? It is not my business to decide whether any penis is involved in their homoerotic relationship. Miss Blais is vague—and blames her characters for not being more precise. For instance, the priest is said

…to go out in search of what Mlle Léonard called “haunts of fornication”…though he, scorning her evasive terms, would have said: “That evening I had the desire to hold a man in my arms.”…

If we want to avoid being “evasive,” we will have to decide whether the priest had an orgasm or not. I don’t know—and don’t care—but my ambiguous phrase, “make love,” seems to cover the possibilities.

I won’t take up your space by setting out the long sentences of Proust and Miss Blais to illustrate my suggestion that the one sort is like a parody of the other. I was criticizing the comic effect, not the length. The publishers, incidentally, compare Miss Blais’s work with that of Genet and Proust—and also Baudelaire and Colette, though the latter two influences are perhaps less evident.

As to the number of cats skinned, see page 177. I agree with Miss Meigs that one would have been enough. As to child-torture, on one page a man goes from one child to another “in a crazed, waltzing stupor,” whipping their faces. A girl’s eyes bleed and her cousin says, with pleasure: “He’s made you bleed just like me.” There are many pages like this. If torture is not “the main preoccupation” of this book’s characters, can Miss Meigs tell me what is?

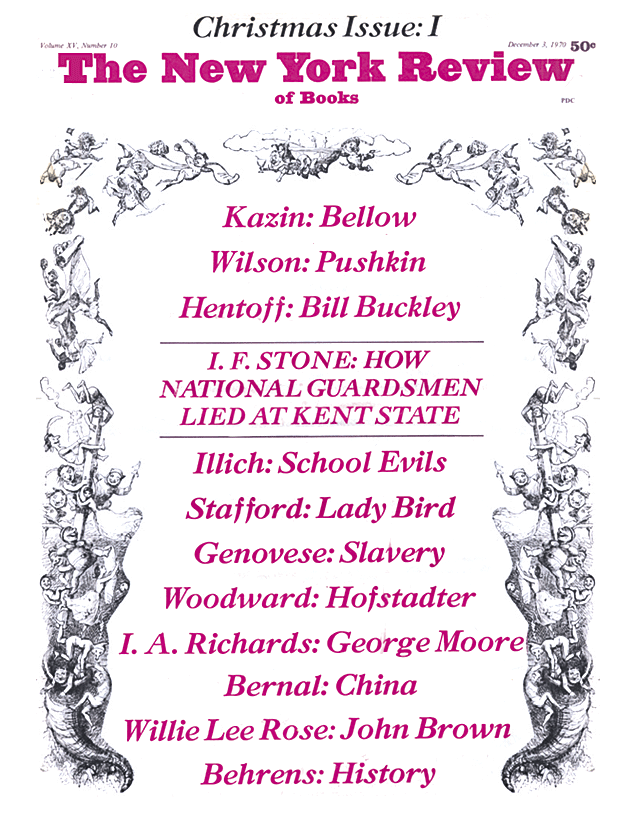

This Issue

December 3, 1970