The Sentimental Education was first published in the Paris of 1869, thirteen years after the triumphant appearance there of Madame Bovary; and the later novel has remained ever since in the long long shadow of the earlier one, waiting for full recognition. The reasons for this preference may seem cogent, at least to the average reader of novels. Thoroughly original in its conception and its language, Madame Bovary still rests on the ancient formula of sin and retribution and so moves steadily toward a decisive end: the suicide of Emma and the ruin of her family. Emma’s adventures dominate the action; one’s attention is the more acute for being fixed on a single line of development.

True, Emma is a wretched woman, and her character and culture are relentlessly dissected by the author. Yet she has the advantage for any reader of being violently real in her physical presence. Her lush irritated sensuality works on one’s own sensuality, even to the moment when, agonizing on her death-bed, she “stretches out her neck” and “glues her lips” to the crucifix offered her by the priest. Emma dying is the same person as Emma living, the literal embodiment of unlimited desire. One might say that she has turned into the very stuff of her daydreams: the stuff of sex and body, of the money, jewels, marriages, draperies, and yards of dress goods she has coveted. And Emma’s ghastly “materialization,” so to speak, has a pathos about it. The impoverished moeurs de province, the phrase Flaubert uses for the book’s subtitle, defeat her efforts to escape them. Confined to her dismal province, she feels permanently excluded from Paris, where all the good things—sex, money, jewels, and the rest—presumably abound.

In The Sentimental Education bountiful Paris is itself the scene of most of the drama. The characters with “life stories” are numerous and rather better endowed than Emma is with culture and experience. Nevertheless they come to ends which for the most part are not decisive ends at all; they just fade away into nothingness. The Paris of The Sentimental Education is “sick” in much the same secondary sense as that word has today. And during Flaubert’s lifetime it was one thing to represent the provinces as “sick,” quite another to represent as “sick” a great city, the capital of a great nation’s culture as well as its government. On its first publication The Sentimental Education was condemned by all but a few of Flaubert’s contemporaries as ailing itself: it was called politically perverse, morally squalid, and an aesthetic failure. Until recently the book has been stuck with that reputation, so far as the large public was concerned, while Madame Bovary has continued to flourish.

Nothing in recent literary history is better known than the contagious fame won by Madame Bovary. Emma’s appeal to readers was equalled by the appeal of the novel itself—its subject as well as the sophistications of its form and language—to young novelists in all the novel-producing countries. Flaubert’s new, exacting realism was adapted to the life stories latent in other provinces, remote from France, where young men and women yearned for other capitals: Moscow, Madrid, New York, even Chicago.

Implicit deep within Madame Bovary, however, is a theme which only the greatest of Flaubert’s progeny have laid hold of—insofar as it was not given by their own experience—and the theme becomes quite explicit in The Sentimental Education; though publicly neglected, the Education soon acquired an underground reputation, especially with writers. This theme was the existential one: the perception of a growing estrangement from “real experience” and the “lived life”—vague terms for elusive but powerful feelings—on the part of individuals living in whatever locale, provincial or metropolitan. This perception was at the heart of Flaubert’s idea of modernity; he and Baudelaire were the first “modernists,” not solely because of the innovations they brought to the art of writing but because each developed powerful conceptions of the nature of modernity itself.

The history of Flaubert’s influence, as the author of both novels and tales like Un Coeur simple, is formidable. It has been a history not of imitations—which don’t matter—but of transformations, unpredictable, brilliant, self-perpetuating. Among the novelists strongly affected there was Henry James, especially in The Bostonians, and later there were Proust and Joyce (not to mention the several French writers who were Flaubert’s immediate disciples). The least predictable episode in this history was the infusion of Flaubertian spirit, together with the Baudelairean-Symboliste spirit, into modernist poetry, chiefly the earlier poetry of Eliot and Pound. As Flaubert had fought for a prose that was as well written as poetry, so Pound fought for a poetry that was as well written as prose—meaning, in part, Flaubert’s prose: its precise rhythms, its acutely particularized images.

Advertisement

Of the two poets, Eliot was the more susceptible to the existential theme, which was localized in his “Unreal City.” Bored, restless, and afraid, the people of the Unreal City are subliminally anxious to hear the saving Word but can only hear the comforting commonplace: “Cousin Harriet, here is the Boston Evening Transcript.” Our knowledge of Eliot has helped us to identify and understand the function of commonplaces and banalities in The Sentimental Education. Mme Arnoux remarks to Frederic: “Sometimes your words come back to me like a distant echo, like the sound of a bell carried by the wind.” Mme Arnoux talks like Eliot’s too baffled, too articulate “lady of situations” in her several guises. The Flaubertian tradition has been a two-way thoroughfare.

Where Flaubert’s influence is concerned, however, qualifications are called for. To his literary progeny Flaubert was assimilable only in part. He was a difficult father figure whose testament was full of discriminatory clauses that seemed to require contesting. His pessimism was too unyielding, his work a triumph of artifice over art, his style a medium too solid to transmit the possible varieties of feeling implicit in his subjects.

Henry James objected that Flaubert “had no faith in the power of the moral to offer a surface.” This delicately phrased judgment is convincing if one agrees with James about how “the power of the moral” asserts itself upon the “surface,” that is, in the necessarily aesthetic style and form of any good novel. For James “the moral” makes itself felt through a series of identifications between the best in the author and the best in his readers, with the characters acting as agents in the transaction: those of his characters, I mean, who at their best are capable of reaching states of consciousness about themselves and their situations, and then of acting decisively on the data of consciousness. For James, experience is the great teacher and the lesson is the primacy of mind, mind as awareness. In his own subtle fashion James was captivated by the Bildungsroman conception of literature. Flaubert was not. James’s New World idealism was alien to Flaubert’s conception of the average human potential in the age of modernity, itself a manifestation of the sovereignty of the average. The Sentimental Education is a negative Bildungsroman. With the characters, the education by experience doesn’t “take.” They learn nothing. For readers, the novel is an unlearning of indefensible sentiments and ideas.

Among Flaubert’s other putative descendants, Eliot and Proust found different exits from the Flaubertian Limbo. For Eliot, the saving Word is really there, even if it comes to us garbled and attenuated, offering partial epiphanies and precarious conversions. For Proust transcendence is the peculiar privilege of the artist, a conclusion that gives his wonderful big-bodied novel, clamorous with suffering, a very small head.

Only Joyce among “moderns” surpassed Flaubert in greatness while possessing a similar vision of human limitation; both writers were of course renegade Catholics. Joyce’s Dublin, like Flaubert’s Paris, is incurably stricken with paralysis (Victor Brombert1 astutely diagnoses the particular Parisian mal as a universal susceptibility to prostitution). Dublin epiphanies range from the frankly false to the merely promising. The immanence of myth deflates reality. Molly Bloom is more Molly than earth mother. In Dublin nothing really happens, nothing transcendent. Dubliners simply reveal, for the reader’s pitying or amused contemplation, the general lifeness of life: people are what they are, not in any past or future imagined by them, but in what they feel and do and imagine at any given moment or hour or day in their lives.

But there was at least one great difference between them. Flaubert’s doctrine of “impersonality” in art was equally an item in Joyce’s literary creed. But impersonality can be “cold” or “warm.” Joyce’s is warm in the profoundly, elusively tempered way that the impersonality of Shakespeare and Cervantes is “warm.” Flaubert’s is cold, with variations here and there. His relationship with his characters tends toward incompleteness; a void is formed which the author’s brilliant irony is seldom capable of displacing. This, to me, is the most problematical element in his work: yet it is not the whole storv of his work. What Mark Van Doren has written about Thomas Hardy, another implacable ironist, is true of Flaubert too: “He is that most moving of men, the kind that tries not to feel yet does.” Flaubert does feel, almost in spite of himself, especially when his subject is the betrayal or exploitation of the helpless: Emma Bovary’s husband; the servant woman in Un Coeur simple; and, in the Education—among several others—Dussardier, the worker who is the captive and victim of his bourgeois friends. The pity that comes easily to certain other writers is the more moving in Flaubert because to him it comes hard.

Advertisement

A recent English, very English, critic condemned The Sentimental Education as “an attack on human nature.” One admits the charge is true, while wondering what is so great about human nature that it should be declared immune from attack. Flaubert’s aloof, melancholic temperament caused some of the bleakness of his vision, as any writer’s negations or affirmations owe something to his temperament. Yet the bleakness is also inherent in an Old World skepticism, a pre-bourgeois désabusement, concerning human nature as manifested in society, the only form in which human nature can be known. In Flaubert the moralism of, say, Montaigne, Pascal, and La Rochefoucauld (and of non-Frenchmen like Swift) survives, with the newly bourgeoisified Paris rather than feudal Paris as the object of his censure or derision. Invoking a writer’s traditions is an easy way of making him respectable. Flaubert was the rare kind of writer, later celebrated by Eliot in a famous essay, in whom a strong sense of tradition interacts with great originality to produce the “new, really new work.”

His immediate precedents for The Sentimental Education were, it would seem, the comprehensive eighteenth-century satires, among which Candide and Gulliver’s Travels were intimately known to Flaubert. Like those earlier satires, The Sentimental Education is an attack on the whole modern spectacle of human bétise, imbecility. Indeed, the Education has always been taken too seriously or with the wrong kind of seriousness by critics who are insufficiently tough-minded or are too humorless to see that the book is essentially if often deceptively comic, anticipating the pure comedy of Bouvard et Pécuchet, his next—and last—important work. “Deceptively” because the comic effect of the Education is generally subdued to conform with the generally dreary realities of bourgeois existence. The method of the satires was comic fantasy touched here and there with realism and pathos; Flaubert’s method is realism touched with the fantastic; many episodes of The Sentimental Education are as outrageously funny as anything in Candide.

Candide was one of Flaubert’s “sacred books”; and the Education forms certain relationships with it that are worth noting. Both narratives move at a frantic pace, “cresting,” like a flood, in a pair of major phenomena, the Lisbon earthquake and the 1848 Revolution; in both narratives, too, the episodes are strung along a continuous thread of romance: Candide’s enduring devotion to his much put-upon dream girl, Cunégonde, and Frederic Moreau’s devotion to his much put-upon Mme Arnoux, a rather mature dream girl. While a playful irony attaches to Candide’s affair, an irony that is alternately light and corrosive informs Flaubert’s account of Frederic’s affair.

The two heroes are essentially unlike. Candide is a thoroughgoing “innocent” whose continuing innocence is guaranteed by his incorruptible good will. Frederic is innocent only by virtue of the Romantic literary convention which tended to attribute this quality to the young, so long, at least, as they stayed young. (Flaubert’s ironic subtitle to The Sentimental Education is “L’Histoire d’un jeune homme.”) In his fine study of the novel,2 Harry Levin calls the mature Frederic “a dilettante who has survived his innocence.” I would only object that Frederic’s innocence and the good will it rests on have been subject to corruption from the start. So while Candide gets his reward, is at last reunited with Cunégonde and they are left cultivating their garden, Frederic loses Mme Arnoux, the possession of whom he has always blown hot and cold about, and is left cultivating his memories.

I mention these parallels with Candide not to pronounce The Sentimental Education a classic by association but, again, to affirm Flaubert’s originality. In part, the originality of the Education consists in his bringing to bear a comic perspective, infinitely variable in its intensity, on a mass of “real life” characters and stories which normally were subject to serious, or occasionally serio-comic, concern, especially in popular novels of the time, like Octave Feuillet’s Roman d’un jeune homme pauvre.

In a larger sense, Flaubert’s manner here is an adaptation of the traditionally French manner of working within deliberately confined borders, the success of the performance depending, like the success of laboratory experiments, on just this principled selectivity. The Anglo-Saxon way is different, sometimes causing philistines of that community, even important philistines like D. H. Lawrence, to belittle the energy of French creation. On this subject V. S. Pritchett3 remarks:

We [English] tacitly refuse to abstract or isolate a subject or to work within severe limits…. A native instinct warns him [the English writer] that he could learn more than is good for him. He could learn, for example, final fatalism and acceptance.

In The Sentimental Education it was Flaubert’s feat, and one that followed from his comic aims, to have made an epic novel out of an accumulation of anecdotes. The novel is epic because the fates of numerous characters and of a major revolution are embraced in the action; it is anecdotal because each episode recounts—as I think anecdotes do by nature—the momentary defeat or the equivocal victory of someone in a particular situation. Each episode extracts from the situation a maximum of irony and then, having made its point with a precision consonant with its brevity, is caught up in the furious current of the enveloping narrative. By itself, anecdotal irony is self-contained, a blind alley. It is irony for irony’s sake, such as is apt to inform the anecdotes that circulate in any group of acquaintances, real or fictional, getting from the reader or hearer only a laugh or amused sigh or a murmured “How typical of him!” Superior anecdotes make for superior gossip as distinct from mere talebearing. And the doings of the members of the circle—mostly career-bent intellectuals and their women—that centers on Frederic Moreau in the Education make for superior gossip. However, the irony itself isn’t finally of the blind alley kind, as the following episode should make clear.

For years Frederic has been trying at intervals to seduce Mme Arnoux, the faithful wife of his friend, the art dealer Jacques Arnoux. Finally she consents to a rendezvous in a room Frederic has rented and beautified for the occasion. But she doesn’t show up. And after hours of frantic waiting and searching, Frederic takes his whore to bed in the same beautified room. Later she wakes up to find him weeping and asks why. “Because I am so happy,” he says, meaning the opposite. In itself the outcome of this little episode may deserve no more than a snort of recognition. “How typical of Frederic!” But this primitive response doesn’t stick. There’s more to it.

The episode crawls with implications, not only amatory but domestic and political; and promptly caught up in the narrative stream, it goes to feed the rising flood of irony which will at last engulf the novel’s entire scene, figuratively speaking. The whore, as I unjustly called her, is really a lorette or kept woman, Rosanette Bron, and is at present the mistress of Jacques Arnoux. Rosanette is beautiful and weirdly charming, by turns affectionate and mean, wonderfully vulgar in her taste for lush boudoirs and Turkish parlors complete with hookahs, and no happier in her profession than Frederic and his circle of fellow intellectuals are in theirs, but a cut above them in her prodigious vitality.

Mme Arnoux, for her part, has failed to keep the rendezvous because, her young son having come down suddenly with a violent croup, she takes this as a judgment on her for her proposed betrayal of what she instinctively values most: husband, children, home; and for years to come she will rarely see the importunate Frederic. Meanwhile, searching the streets for her, he hears a noise of rioting on the distant boulevards. “The pear is ripe,” he soon reads in an excited note from his friend Deslauriers. Deslauriers is trying to involve Frederic in the political struggle against the degenerate monarchy of Louis Philippe, an involvement that Frederic, busy with his love affairs, prefers to avoid. In short his amatory mix-up coincides with the outbreak of those disturbances which, extending from February through June, will be known to history as the Revolution of 1848.

As reported by Flaubert, the uprising generates its own irony and contributes to the epic, or mock-epic, character of the whole novel. It is not only the political “commitments” but even more the personal “motivations” of the participants that naturally fascinate the novelist—the participants including people of all political persuasions, not least the rich banker, Dambreuse, who promptly declares himself a republican.

And just as their motivations, better and worse, color the actions of people during the Revolution, so the actions are sometimes heroic, oftentimes fatuous and self-serving. Flaubert’s account of the uprising is, again, episodic, his tone dispassionate. He doesn’t want to make a monumental set piece out of an event which will turn out to be, from his viewpoint in the novel, a tragic farce. So he touches in more or less detail on such episodes as the abdication and flight of Louis Philippe; the eruption all across Paris of political meetings and street battles; the sacking of the Tuileries palace by a mob; certain incidents connected with the gradual concentration of power in the middle classes and their military force, the National Guard; certain incidents connected with the corresponding loss of power by the working classes; the final defeat of the proles; the imprisonment of hundreds of them in vaults beneath the Tuileries facing the Seine where they are left to starve. In one instance an imprisoned youth who screams too insistently for bread is shot to death by Old Roque, Frederic’s miserly home-town neighbor who has hastened down to Paris to take his stand in the National Guard and who commits this decisive act in defense of private property (the memory of it sickens him a little, but not for long).

So the Revolution itself is caught in the embrace of Flaubert’s irony. Just as the proletariat is put down by the Republican middle classes, so those classes are presently put down—or bribed to surrender—by Louis Napoleon when, in his coup of 1851, he converts the Second Republic into a Second Empire with himself as Emperor. Flaubert soft-pedals this development, possibly because Napoleon III was still in power and his censorship still in effect when Flaubert wrote the novel. But the implications of the coup are made clear. Louis Napoleon has dreamed of playing the same role that his uncle, Napoleon the Great, played when, in 1799, he proclaimed the First Empire, with himself as Emperor, thus terminating the Great French Revolution of those years, and leaving France, with its burden of half-resolved problems, to a century of turmoil. Two years after the Education appeared, Napoleon III would be defeated by the Prussians and driven from France. Paris would again be the scene of a working-class uprising (the Commune) which would again conclude with the slaughter of rebellious proles.

Flaubert’s own politics, if any, were protean in the extreme. One might call them, paradoxically, a politics of non-commitment, except that he did now and then react impulsively, and stupidly, to events. He had been no more than a spectator of certain actions in ’48, having been in Paris at the time more or less by chance. But his instinct for detecting the convulsions at work deep within the society was steady, profound, and, alas, prophetic. What Henry James called, in a misguided attempt at reductive wit, Flaubert’s “puerile dread of the grocer” was a dread of the entire acquisitive culture which corrupted, or threatened to corrupt, grocer, banker, and worker alike. Flaubert was far less knowledgeable about society than Balzac or Dickens were. Nevertheless, as concerns his visionary pessimism and its effects on his art, there was a point in his refusal to identify his fortunes with those of any existing or pre-existing social class, aristocratic, big bourgeois, little bourgeois, or proletarian. Having no faith in the power of the social—that is of reformism or revolutionism—to offer a surface, he made what he could of his unimpeded, unqualified bleakness of vision. He made, chiefly, The Sentimental Education, and the world has now caught up with the bleakness.

“The first time as tragedy, the second time as farce,” Karl Marx wrote of the coups d’état of the two Napoleons, in words that have been often quoted since. Flaubert views the events of the years 1848-1851 in a similarly theatrical spirit, though with less hopeful implications for the future of France and its working class than those entertained by Marx.4 In 1835, as a boy of fourteen, Flaubert had observed in a letter to a school friend that “our century is rich in bloody peripeties.” Such peripeties, as they affect the characters of the Education, bring the harsh comedy of the novel to a climax. The tragic farce of the revolutionary years is a large-scale political manifestation of the farces, bitter or merely ludicrous, enacted by the characters in their individual lives.

The fiasco of 1848-51 hastens and intensifies all the processes at work in the novel. The temporal process is one of these; it pervades everything, and accordingly accelerates in the years following the Revolution. Yet there seem to be two kinds of time at work in the Education, and since the two interact in devious ways, neither is easy to define in itself. The first and more obvious may be identified with what we call “clock time.” It consists of the hours, days, months, and years—often specified by Flaubert—during which Frederic and his circle pursue the objects of their various ambitions. The wretched painter Pellerin boasts that “art, learning, and love—those three faces of God,” are solely on view in Paris. And Paris, insofar as it is assumed to enjoy this exclusive privilege, represents the pure present, an eternity of now.

Generally invisible to the characters, therefore, are the monuments of the city’s past. In Flaubert’s descriptive patches, they appear rarely: reminders of what Frederic and company tend to ignore. Frederic is first seen aboard the steamer bound for his home town of Nogent-sur-Seine. As the steamer pulls away from the quay and up the Seine, he gazes regretfully back at the city. “He peered through mists at bell towers and buildings whose names he did not know,” while glimpses of Notre Dame and the Cité merge in his eyes with glimpses of riverside “warehouses, yards, and factories.” Caught in the unlimited present, physical Paris is to the characters a faceless configuration of streets, shops, cafés, restaurants, and residences, among which they hustle, trying to meet or avoid meeting one another, and generally contesting for place and preferment like the checkers on an immense checkerboard.

By contrast, the countryside is reserved for holidays and duty visits, and there time’s action is naturally decelerated, at least for the Parisians; sooner or later they must be off to the metropolis. It is the presence in the country of the Parisians and the Parisian idea that injects into these rural scenes the peculiar Flaubertian compound of yearning dreariness and elegiac charm. Here as in Madame Bovary some of his greatest passages are devoted to bringing out, through people’s behavior, through the look and feel and smell of trees, rivers, gardens, palaces, and houses, this intermingling of past and present France, of artificial and natural time, of pastoral “poetry” and realistic “prose.” No country scene in the novel is without its intrinsic serenity, no country scene fails to excite an intrinsic anxiety.

In the two chief country-based episodes, one in Frederic’s home town of Nogent, the other at Fontainebleau, love itself partakes of these contradictions, flowering on the serenity, withering with the anxiety. At Nogent as at Fontainebleau the presence of the past is complicated: in both places there are pasts within pasts. At Nogent Frederic wanders with Louise Roque among waterside gardens strewn with the broken statues and ruined pavillions of a Directoire “folly.” Louise is the neighbor girl, once an illegitimate waif, now a potential heiress, who has always adored Frederic. Since he is at present low on funds and she will have money, it is now vaguely understood between them that he will propose marriage. Together they sit on the river bank and play in the sand like children, Louise hinting that the clouds are floating toward Paris.

Her passion for Frederic is awkwardly but violently physical; she envies the way fishes live: “It must be nice to glide in the water and feel oneself stroked all over.” The two have reverted to their own pasts, but not for long. On the premises there is a big wood shed, and when Louise suggests they go inside it Frederic is embarrassed and ignores the suggestion. She breaks into frank reproaches—the frankest and truest he ever gets from anyone—and the pastoral idyl limps to an end. The Parisianized Frederic has refused to play his appointed role in the idyl. And Louise is left to ripen within the retarded medium of rural time—to ripen, alas, into bitterness.

The idyl motif recurs with variations in the later passage that describes the visit of several days that Frederic and Rosanette pay to Fontainebleau hoping to get away from the turmoil of revolutionary Paris. Here too there is a monument to an earlier past within the perennial splendor of the great wooded park with its radiating carriage roads, its sunny clearings, deep glens, and outcropping of ancient rock. The monument is the Palace itself, heavy with grandiose mementos of Henry II and his mistress Diane de Poitiers. The Palace excites in Frederic one of his sudden “frenzies of desire,” this one “directed toward the past.” But Rosanette is bored and weary and can only say, “It brings back memories.” In a way it does. But her memories concern herself—her past as an impoverished working-class girl in industrial Lyons, turned lorette at the age of fifteen. Her thoughts concern herself and Frederic, whom she too adores, momentarily at least, dreaming of a lasting affair with him. (“One day she forgot herself and told her age; she was twenty-nine and growing old.”)

They daily explore the forest in a carriage, happy with each other, feeling a “thrill of pride in the freer life.” Yet misgivings shadow their pastoral excursions. They recall other lovers, she Arnoux in particular, he Mme Arnoux. Each yearns discreetly for the lover who is absent. By turns the forest soothes and disturbs them. The vistas into its dark interiors gloom at them; the rocks take on the shapes of wild beasts coming at them. One day Frederic finds in a newspaper Dussardier’s name on a list of men wounded at the Paris barricades. Dussardier is a young man of heroic size and strength, the one authentic worker in Frederic’s circle. It is late June and the workers are making their last stand. Frederic and the reluctant Rosanette leave for the city, Frederic finally getting into Paris alone, past barriers and guard-posts manned by suspicious National Guardsmen, past ruined barricades and shot-up houses, to the attic room in the house where the wounded Dussardier lies.

Meanwhile Flaubert’s Paris, citadel of the pure present, is also subject to the workings, barely perceptible though they are, of natural time as distinct from artificial or clock time. Natural time flows through the city with the river, drifts across its skies with the mists and clouds, manifests itself in the succession of day and night, in the changing seasons, in the winter wind that reddens Rosanette’s cheeks, in the setting sun whose rays—in Frederic’s rather mercenary imagination—cover buildings with “plates of gold.” If he is more susceptible than others are to these presences, it is, again, never for long. Pausing on bridges, he has exalted visions which, however (as Harry Levin points out), quickly resolve themselves into dreams of instant acquisition.

Parisian epiphanies, Parisian dreams. Yet it should be said that, whatever Flaubert himself thought of the city—and his pleasure in it was intermittent—he shapes the Paris of the Education to his own selective purposes in the novel. Those purposes have their bit of common truth vis-à-vis the real Paris. Surely Paris was, and is, a great city if there ever was one. It lends itself to satirization (in how many works besides the Education!) because its sillier inhabitants are tempted to believe that the city’s greatness rubs off on them, causing them to feel unduly self-important.

Pellerin’s “three faces of God” slogan is the reduction to nonsense of this Parisophiliac madness. Pellerin himself, like so many of Frederic’s copains, suffers from this gratuitous sense of privilege. Haunted by the idea of art, he never makes it as an artist in fact. The actual endowments of les copains are unequal to the expectations they have of themselves as Parisians or Parisianized provincials. They remain artists and intellectuals manqués. Flaubert knew that they were special types of the Parisian. Scattered through the pages of the Education are the names of actual, and variously distinguished, men of the period. Corresponding to Pellerin there are Géricault and Delacroix; to the sometime littérateur Frederic, Hugo, Chateaubriand, Lamartine; to the radical Senecal, Proudhon, Barbès, Blanqui, Louis Blanc. The Paris that harbored such men has eluded time in all senses, and lives on in an eternity of deserved fame.

The varieties of time are merged into a single powerful force by the happenings of 1841-51. As the crisis deepens, Flaubert’s characters undergo the same rapid changes of heart—from fear to exaltation to final disgust and fatigue—experienced by the populace at large. Individual weaknesses come glaringly to light; everyone grows confused, demoralized, desperate. Even Dussardier is confused. The good if simple-minded prole has been beguiled, as many proles actually were, into fighting with the bourgeois National Guard during the June days. Now, his huge body stretched wounded on his bed, he begins to suspect that he has fought on the wrong side. He has assaulted a fellow worker at the barricades. Presently Dussardier himself is shot to death by a policeman newly recruited to keep order in Louis Napoleon’s Second Empire. The policeman is Dussardier’s old friend and mentor, Senecal, once known as “the future Saint-Just,” long a strenuous advocate of Socialist discipline, scientific logic, proletarian literature, and progress. Senecal’s motivation has been in excess of his Socialist commitment. His real commitment is to power, even if exemplified in the lowly figure of the policeman with uniform and gun.

No other incident connected with the general decline is as lurid—and prophetic—as this one. Frederic and the remaining copains merely prey on others, and on each other, in their abasement before the new God of three faces: sex, money, and power. Much that happens in the new situation is merely ludicrous. There is “the magazine” and its change of heart. Les copains have long struggled to start and keep going the precious periodical without which no intellectual circle is complete. Their periodical now ends up as a gossip sheet. Frederic’s development is scarcely more interesting. He terminates his quest for greatness by trying, and failing, to marry money.

Only one member of the group survives intact, preserved by the remarkable system he has imposed on his life. He is the stern republican, Regimbart, known as “the Citizen,” and his system consists of his rushing around Paris each day in order to be present in the same cafés or restaurants at the precise hours scheduled for his presence at these establishments. Regimbart’s regimen has constituted his career. Come revolutions or coups d’état, he remains the useful Parisian citizen, a sort of human clock, a walking landmark.

One tends to dwell with special delight on Regimbart and others of his type in the circle of copains that surrounds Frederic Moreau. Frederic, for reasons that I will go into later on, is not himself a compelling character, although he is the occasion for much anecdotal amusement. Nor are the habitués of that other Parisian scene, the Dambreuse salon, compelling either. The rich banker Dambreuse, a bourgeoisified nobleman, and his sleek fashionable wife, later widow, whom Frederic woos for her money, are puppets; their world is a pastiche of Balzac’s world.

Regimbart and his type are not puppets. Regimbart, Senecal, and Pellerin, for instance, are lively grotesques, literal embodiments of their obsessive ideas. Frozen in their characteristic attitudes, they are like figures in Daumier, just as the milder people and their characteristic settings, the studio scenes, the rural scenes, recall those of Courbet. There is, I believe, nothing quite like les copains elsewhere in literature, whether in the intellectual milieux of Dostoevsky’s Petersburg or of Joyce’s Dublin. Only in Paris, where the cultivation of arts and ideologies counts for so much in the high French culture, could such debased types of the artist and ideologue as Frederic and company be found in such profusion.

No doubt the type of the intellectual manqué fascinated Flaubert, and for reasons that form part of the well-known Flaubert legend. Acknowledged master though he became at the age of thirty-six with his first publication, Madame Bovary, he had in him at all times a good deal of the perpetual amateur, the compulsive dreamer, the man of obsessive ideas. Born in 1821, he was admittedly, proudly, a belated Romantic. Precociously literary from childhood, he was given to revering, as if they were holy relics, certain images of past beauty: old stones recalled from a visit he made to the Acropolis; old paintings in oil or glass studied in cathedrals or museums; old books—Candide, Don Quixote, Rabelais—continually reread and pondered through the years; old professions, like sainthood, monkhood, and prostitution; old friendships and exalted moments in his life. Familiar too as part of the legend is the detestation he nourished for the present, the age of “the grocer,” as a corollary of his passion for the past. The present was given over to the worship of commodities, so much so that people, their possessions, their careers, their speech, their very dreams belonged to the commodity realm.

Divided souls like Flaubert’s were of course common in the emergent industrial democracies of the mid-century and on into our own time. The type has produced connoisseurs, collectors, critics, professional travelers, and, when the luck was good, fine writers, major and minor. Flaubert became a major figure in this tradition, partly by practicing in his literary work a unique form of the division of labor. He split his writings into historical fictions and fictions of contemporary life, while composing all of them with the same attention to style and form. To the world of his historical fictions (Salammbô, La Tentation de saint Antoine. La Légende de saint Julien l’hos pitalier, Hérodias) he assigned the qualities he worshiped in the past: the heroism, idealism, romance, beauty, and so on; while to the novels of contemporary life (Madame Bovary, L’Education sentimentale) he relegated, so to speak, his sense of the modern materialization of life. As he practiced it, the division of labor had its limitations. It was mechanical. Whether for this reason or another, the bulk of his work was small in an age when novelists were prolific, almost by definition.

The bulk of his unpublished work was considerable. He lived amid a clutter of dormant manuscripts, the continually expanding archives of his restless creative spirit (many of these items have recently been exhumed and put into print). There were the notebooks; the first drafts; the more or less completed works that never saw print (among them an earlier version of The Sentimental Education); the assorted early projects that remained fragmentary; the plays that were unproducible or, if produced, as Le Candidat was, were flops; the fairy tale briefly worked at in collaboration with friends; the Dictionnaire des idées reçues, a compilation of clichés to which he added items through the years and which was to have formed an appendix to Bouvard et Pécuchet, the great extravaganza of which he had completed ten chapters when, in 1880, he died.

In addition, letters to friends poured from him in daily profusion: they now fill thirteen indispensable volumes in the posthumously published Corréspondance. The letters testify in dizzying detail to the quality of Flaubert’s mind. His mind was more than chaotic: protean, it was by turns adult, juvenile, kind, cruel, masculine, feminine, myopic, prophetic, supremely fantastic, supremely intelligent.

Given his genius, there were advantages in being, as Flaubert was, subject to epileptic seizures. He could produce extraordinary masterpieces and still live with his devastating knowledge of the precariousness of everything, one’s genius included. To George Sand he confessed when he was quite old: “One doesn’t shape one’s destiny, one undergoes it. I was pusillanimous in my youth—I was afraid of life. One pays for everything.” The condition of his existence was that he remain vulnerable, and for this too he ungrudgingly paid—to the extent, finally, of surrendering to his grasping niece whom he loved, and to her feckless husband who faced bankruptcy, much of the income on which his precious independence had rested, and then of looking about for jobs, as librarian or whatever, to support him in his old age.

As the letters make clear, Flaubert himself was not the Flaubert of the invidious literary legend contrived by critics, whose praise for Flaubert’s “technique” has been relative in intensity to their distaste for his unseemly habit of self-exposure, his extremism, in his novels as well as in his letters. The letters show that Flaubert was not the “confident master of his trade,” the “technologist of fiction” that some critics have called him. His kind of realism, compounded of observation, research, and certain specialties of style and construction, was no fool-proof method. It was a looming idea, which he sought always to realize in different ways in his writings. Great innovator in fiction as he was, he re-created his innovations from work to work. Each work was a fresh start, preceded by anxious deliberation, accompanied in the actual writing by attacks of self-doubt, depression, panic, boredom, disgust. True, his pride in his Idea and his finished work was great, and so was the almost Johnsonian authority he exercised over other writers of his time. Yet the pride and the authority rested on a consciousness, acute and pervasive, of possible failure. The great artist in Flaubert represented a continually renewed triumph over the artist manqué in him.

His bond of sympathy with les copains and their women, when they have women, is therefore firm—firm in the degree that the sympathy is negative. Among them we find, perhaps, a couple of more or less “lovable rogues,” if the traditional phrase really applies to Arnoux and Rosanette: one betrayed “saint” (Dussardier), and one woman (Mme Arnoux), who remains a veiled figure of presumptive goodness until, at the last, unveiling herself, she shows slight traces of being what was called in old novels about fallen women “damaged goods.” But the fates of all, in particular that of Frederic, involved the broader problem of human freedom, a problem that is broached more explicitly, with more philosophic flair, in French literature than in most other literatures.

French writers in the tradition of Montaigne and the rest generally raise the question in a negative manner. They harp on the data of human unfreedom: the perverse impulse of people to enslave themselves to false ideas, ruinous passions, unwarranted pride. In this matter, again, Flaubert perpetuates a tradition by transforming it. His characters abase themselves before the very phenomena of their time that are presumed to liberate them. There is the prevailing idea of progress itself. There are the comforts and luxuries, the printed books and periodicals, the lithographed art works (“the sublime for sixpence”) provided by the new industrialism. Most ironically, there are the promises explicit in social revolutions (“No more kings! Do you understand? The whole world is free!”). Enslavement to material affluence and vocational opportunity produces its own kind of moral failure. Frederic, in whom this kind of failure is enlarged, as under a microscope, names it when in the final scene he casually remarks to Deslauriers, “Perhaps we let ourselves drift from our course.”

Drift! Flaubert did indeed have a faith in the power of the moral to offer a surface, and drifting is perhaps the precise word for the moral sickness of his Paris. A man like Frederic is incapable of fully recognizing the operation on himself of this universal force, which motivates our achievements while surviving them, prompts us to make commitments while working to eventually undermine them. A Frederic is congenitally unable to reach those ideal states of consciousness which signify the power of the moral for Henry James. Drift is one of those elemental human phenomena, like hunger, of which James is perfectly aware but which he keeps in the background of life, for his own admirable purposes as a novelist. Drift occupies both the foreground and the background of The Sentimental Education.

Given this general concern with human freedom, French novelists are fairly consistent about the degree and kind of volition allowed to the characters in their fictional worlds. In general, Stendhal’s is a world of the probable, Zola’s of the necessary, Flaubert’s of the plausible. The “average sensual man” of common realism is largely of his making. But Flaubert brings to this humdrum domain the dashing energy of primary creation. His mastery of the invention juste more than equals his better known mastery of the mot juste, or precisely chosen word. Perhaps, as I said, his inventions owe something of their apposite brevity to the anecdote—the ideal anecdote which after making its ironic point goes on to waken in the reader amusing recognitions, poignant identifications. Ourselves may be Frederic. Among our friends may be a Deslauriers, a Pellerin, a Senecal, a Louise Roque, a Rosanette.

Even so, Flaubert’s invented actions have a remarkable way of being unpredictably predictable. He seems to affirm the plausibility principle of realism, its capacity to liberate rather than to confine the imagination, by often stretching things to the verge of implausibility. His intellectuals manqués and their women lend themselves readily to this kind of testing. In the men, the ambition to create is strong but the relevant concentration, patience, and intelligence are nil. And it would seem to be the very extravagance of their exertions in this moral void that makes for much that is grotesque, fantastic, and ironic in the spectacle of their existence as mirrored in the Education.

By way of illustration, two highly developed scenes, first the masked ball and second Frederic’s last important encounter with Rosanette:

At Rosanette’s ball, Frederic and many of his acquaintances are present. Most of the guests come dressed as gypsies, Turks, angels, sphinxes—an assortment of standard disguises. Quite naturally, the party’s mood changes from hour to hour, going from gay to raucous to boring. But as the dawn light comes through the windows, surprising everyone, the mood turns desperate. The entire scene—people, costumes, furniture—resolves itself into a tangle of debris, a riot of hysteria. “The sphinx drank brandy, screamed at the top of her voice, and threw herself about like a madwoman. Suddenly her cheeks swelled; she could no longer hold back the blood that choked her. She put a napkin to her lips, then threw it under the table.” For Frederic “it was as if he had caught sight of whole worlds of misery and despair—the charcoal stove beside the truckle-bed, the corpses at the morgue in their leather aprons, with the cold tap-water trickling over their hair.” The ball has become a danse macabre, as in so many death-in-life party scenes in Proust, Mann, Joyce. Yet the symbolism of Flaubert’s scene is qualified by the everyday realism of it. The remaining guests leave to go about their business. Pellerin has a model waiting. A woman has a rehearsal scheduled at the theater. “Hussonet, who was a correspondent of a provincial journal, had to read fifty-three newspapers before lunch.”

Symbolic invention also contends with plausibility in the second of these exemplary scenes. Rosanette had originally become Frederic’s mistress because, terrified by the first uproar of the Revolution, she had thrown herself into his arms and because he had at last summoned the brute nerve to take advantage of such a situation. As a professional, Rosanette has since had other lovers along with Frederic. But she still longs for money, sex, and affection. Her vitality is more and more concentrated in her hunger for some kind of lasting attachment. But with whom among the several men in her life? Arnoux? Frederic? The actor Delmar? She doesn’t know, nor would most of these men be available for a lasting affair, even if she did know. Well, there is Frederic, of whom she is fond and whose vagueness of temperament makes him seem available, especially since Mme Arnoux, his dream girl, seems to him unavailable.

Rosanette has a child by Frederic but the child, a boy, dies in early infancy. Rosanette is frantic. “We’ll keep him, won’t we?” she asks Frederic and wants to have the skinny little body embalmed and preserved indefinitely in her rooms. Instead Frederic suggests that Pellerin be asked to paint the dead baby’s portrait. Pellerin arrives promptly. No commission is unacceptable to him so long as he can paint the subject in his own manner—that is, as he says, in the manner of Correggio’s children. Or those of Velasquez or Lawrence. Or of Raphael. “So long as it’s a good likeness,” Rosanette says. “But what,” Pellerin cries, “do I care about a good likeness? Down with realism! I paint the spirit.” He decides to do the portrait in pastels.

The result when shown to Frederic is a mess. Painted in wildly clashing colors, his head resting “on a blue taffeta pillow among petals of camellia, autumn roses, and violets, the dead baby is now unrecognizable.” But the little corpse remains unburied for an unspecified time, while Rosanette keeps gazing at it, seeing it as a young child, a schoolboy, a youth of twenty. “She had lost many sons. The very excess of her grief had made her a mother many times over.” The idea behind all this seems Balzacian or Dickensian in the extravagance of its pathos, but the passage remains pure Flaubert in its understated brevity. Another tragic farce has been played out, in miniature.

Frederic Moreau is not one of Flaubert’s triumphs of invention as applied to character. He is scarcely a character at all, and the fact that he is by intention the novel’s unheroic hero, a prototype of the modern anti-hero, doesn’t alone explain his dimness. Like Bloom and many lesser modern examples of the type, the anti-hero can be a character among the other characters in a novel, visibly occupying space as they do, making himself felt as they do by his physical presence, the sum of his distinctive modes of speech, gestures, movements, whatever. Apparently Frederic was his author’s alter ego, the sum of Flaubert’s own refusals and malingerings; and one’s alter ego is apt to be a shadowy creature by nature. Frederic is all symptoms and no “surface.” Flaubert knows him too well, sees through him with a clairvoyance that dissolves its object. The author’s self-punishing hand is monotonously present in his hero’s thoughts and actions.

The actions can be marvelous in themselves. For example, Frederic decides to become a politician during the Revolution and so goes to make a speech at a noisy meeting where speakers are shouted down with slogans (“No more matriculation!” “Down with university degrees!” “No, let us preserve them; but let them be conferred by the people”). When Frederic’s turn to speak finally comes, the platform is seized by “a patriot from Barcelona,” who harangues the audience in his native Spanish, a language nobody understands. Frederic leaves the hall, disgusted with politics as a vocation. Frederic is Flaubert to the extent of having the same birth date and background that Flaubert had: the provincial home town, the superior social standing, the forceful widowed mother.

Dim though he is, Frederic has an essential part to play as the center of the innermost circle of characters. His symptoms, as distinct from his character, become interesting when he is seen in relation to the other members of the circle. Those who make it up are, besides Frederic, Deslauriers, Arnoux, Mme Arnoux, and Rosanette. In the economy of the novel, these five are reserved for intimate inspection at the point in their personalities where social and emotional charges explosively meet. The five of them form a series of interlocking triangles, which are subject of course to frequent interference from the “outsiders”: Mme Dambreuse, Delmar, the lurid, enigmatic career woman, Mlle Vatnaz. What brings the five together, apart from their social ambitions, is an intricate configuration of emotional states: love and lust, love and marriage, love and friendship, love in friendship.

Primary, by reason of its unparalleled duration, is the friendship of Frederic and Deslauriers, the poor, mistreated, lonely, unloved, and unlovely youth who becomes a lawyer by profession but will do anything that promises to relieve his desperate poverty and self-hatred. On Frederic’s part, the friendship is based on habit plus his need, from time to time, of Deslauriers’s special kind of devotion. Deslauriers, however, really loves Frederic, with a love that is definitely though discreetly shown to have a physical side to it. In his eyes Frederic’s good looks have something “feminine” about them. This impression explains, or perhaps justifies for him, the warmth of their frequent embraces, which otherwise are just manly Latin hugs. It explains much else: Deslauriers’s jealousy of Frederic’s friends; in one case his resentment of his own mistress, whom he cruelly denounces when she intrudes on the scene of one of their embraces; the fits of animosity that punctuate his relations with Frederic; his conviction that Frederic with his intermittent income owes him not only a living, so to speak, but a share in the hearts and beds of Frederic’s women, whom Deslauriers covets one after the other. In his milder way, Frederic is subject to a similar tangle of feelings for the Arnoux, husband and wife. Fond of the rascally, philandering, amusing, good-natured Arnoux, a gourmet of life, an attenuated Falstaff, Frederic covets Arnoux’s women, his wife and Rosanette, his mistress. The whole affair thrives on feelings which are, variously, filial, maternal, paternal, and sexual. Rosanette, on the other hand, is, as we have seen, given to bestowing her pent up affections on whoever is available, including her dead infant, although Arnoux is her favorite. “I’m still fond of the old goat,” she tells Frederic at Fontainebleau.

Any mere initiate into the deeper psychology can see that Frederic’s instability, emotional and vocational, arises from his unconscious desire to remain a child, with a child’s privilege of changing his mind and his allegiances at will; to the inevitable question, “What will you do when you grow up?” the child, like Frederic, has at his bidding any number of answers. Frederic is by turns “the future Sir Walter Scott of France,” a painter, a politician, a man of the world. The friends and lovers who surround him make up a substitute family, complete with possible fathers, mothers, brothers, and one “kid sister” (Louise). His sexual desires for them are at once stimulated and constrained by the incestuous implications of the desires.

His protracted, never consummated, affair with Mme Arnoux must be understood in the light of these subconscious impulses. Critics have always tried to view the affair as a genuine sublimation. It is the Great Exception, the Saving Grace, in a novel that is otherwise totally disillusioning. One commentator, Anthony Goldsmith, the translator and editor of the Everyman’s Library edition of the Education, sees the affair as a “pure romance,” exempt from the evils of the World, the Flesh, and Time. To another, Victor Brombert, whose study of the novel is the most accomplished I know of, “Frederic acquires nobility” from the affair. “For the sake of this ‘image’ [that of the unattainable Mme Arnoux] he has in the long run given up everything.”

Such ideal interpretations rest partly on the established fact that Flaubert transferred to the Frederic-Mme Arnoux affair certain of his own memories of a boyhood infatuation, also never consummated, for a certain Mme Elisa Schlésinger, whose husband was, like Arnoux, feckless and faithless. Doubts have nevertheless been recently cast on the nature and the duration of Flaubert’s love for Mme Schlésinger. 5 It is supposed that he loved her, as he did others—for example his sister, who died young, and a male friend who also died young—in memory only, and his memory, as we have noted, was a wonderful storehouse of sacred things and moments. He actually saw Elisa rarely in later life, and probably saw her not at all after she and her husband moved to Germany, where she died at a great age, following a series of confinements in a mental hospital. There she was visited by a friend of Flaubert’s who reported that Elisa, thin and white-haired, was a lovely woman still.

To examine at all closely the passages in the Education that concern the Great Affair is to suspect that, in adapting the original relationship to his purposes in this novel, Flaubert gave it a searching look. In the Education there are, to be sure, charming scenes between Frederic and Mme Arnoux. Troubled by the conflict between her fondness for Frederic and her attachment to husband, children, and home, she is touching. Mme Arnoux speaks little, and what she does speak are quite conventional sentiments. Yet she means them, and her speech is the more affecting because it is so unlike the loud, self-serving, sloganeering speeches of les copains. Frederic’s part in the affair is another matter. He alternately admires her from afar and tries to seduce her. His doing this may be only “human,” but does it make him “noble”? On the contrary, one agrees with Mme Arnoux that her son’s sudden illness is a kind of judgment on her and on Frederic, and that she is right to avoid him.

Yet in the long run she is corrupted or half corrupted, though not entirely by him. Arnoux’s ventures into “the popularization of the arts” have gone from pretty bad to atrocious, financially and artistically. Only a loan from Frederic has saved him from disgrace, and following this episode the Arnoux family has disappeared into Normandy for some sixteen years. The Mme Arnoux who, after this long separation, suddenly turns up alone one evening in Frederic’s Paris apartment is much changed by her sufferings, her isolation, and the sheer impact on her of Time.

The scene that follows between them has been described as “heartbreaking.” It is heartbreaking chiefly in its falseness, in the sad failure of the two to rise to this putatively great occasion. There are exchanges of reminiscence, professions of eternal love, all in the kind of language that must have been taken for passionate in popular novels like Le Roman d’un jeune homme pauvre. Frederic is “drunk with his own eloquence”; while Mme Arnoux, her former restraint gone, is all breathless banalities. Telling him how she often broods by the sea, she says: “I go and sit there on a bench; I call it ‘Frederic’s bench.’ ” (It sounds no better in French.) Her sufferings and her age have made of Mme Arnoux a sentimentalist.

Frederic, for all his rapture, lies to her twice. She has brought him, in a velvet purse embroidered by her own hand, the money owed to him by Arnoux. He makes no move to refuse it. When she finally removes her hat and Frederic discovers that her hair is white (like Elisa’s), he suspects that “she has come to offer herself to him.” He recoils from the suggestion for reasons which, as Flaubert lists them, build up to a stunning anti-climax: “he was seized with a stronger desire than ever—a frantic, ravening lust. Yet he also felt something he could not express—a repugnance, a sense of horror, as of an act of incest. Another fear restrained him—the fear of the disgust that might follow. Besides, what a nuisance it would be! And, partly from prudence, partly to avoid tainting his ideal, he turned on his heel and began to roll a cigarette.” What can the poor woman do but exclaim, “How chivalrous you are!” and depart forever, after first cutting off a lock of her white hair to leave with him as a souvenir? Do his wildly mixed motives add up to chivalrousness or “nobility”? And how can Frederic be said to have “given up everything” for her image when his entire existence has been a series of uncompleted moves on the checker-board of life? The big scene is a fiasco.

One’s skepticism about Frederic and the Great Affair is confirmed by the final chapter, often called the “epilogue” of the Education. Frederic, now in his forties, and Deslauriers have been reconciled after a long separation on their part and are alone together. Reliving their pasts, they hover between mild regrets, mild complacencies, and tentative self-reproaches. (“Perhaps we let ourselves drift from our course.”) They end by recalling an incident from their boyhood. In his first chapter, Flaubert has sketched in the little incident very lightly, leaving it to the mature Frederic and Deslauriers to clarify the importance which the incident has—for them. As boys in their teens at Nogent they had decided one Sunday to visit the town brothel. On arriving inside, Frederic bearing a bouquet of flowers, they had been laughed at by the girls and Frederic, embarrassed, had fled the place, and because as usual Frederic had the money, Deslauriers had fled too. Recounting the story in detail, the two men agree on its significance: “That was the best time we ever had.”

That a long crowded narrative should conclude in this flippant manner has shocked many readers. Other long crowded novels end with real denouements, in which the complications of the plot are unraveled, the hero is reformed, and the ironic tensions are relaxed. For this long crowded novel, however, Flaubert’s epilogue is the perfect ending. The original brothel incident makes a miniature anecdote. That incident, as recalled and moralized by the middle-aged participants, is the apotheosis of the anecdotal form. It resolves nothing, leaves the hero unreformed, and perpetuates into the indefinite future the ironic tensions, the equivocations of drift, and the operations of the World, the Flesh, and Time.

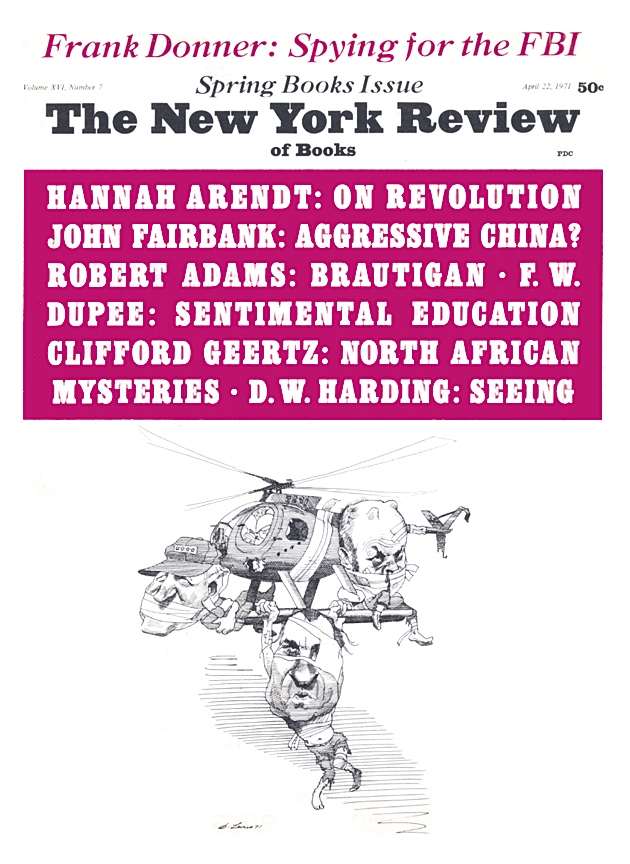

This Issue

April 22, 1971

-

1

The Novels of Flaubert, A Study of Themes and Techniques (Princeton, 1967), $7.50; $2.95 (paper). ↩

-

2

The Gates of Horn: A Study of Five French Realists (Oxford, 1963). ↩

-

3

“A Love Affair,” in Books in General (Harcourt, Brace & World, 1953), p. 104. ↩

-

4

For a modern account of the 1848 Revolution in its pan-European as well as its French aspects see Lewis Namier, 1848: The Revolution of the Intellectuals (1946). Namier’s judgment, supported by the failures of revolutionary or Irredentist uprisings in Central and Eastern Europe and in Italy, is close to the judgment of Marx and of Flaubert: “In February 1848, in Paris, political passions devoid of real content had evoked revolutionary phantoms [phantoms of the Great Revolution] Once more the traditional revolutionary cries were heard, but there was no élan, no sacrificial zeal All over Europe the middle classes paid lip-service to the ‘people’ and its cause, but never felt altogether secure or happy in its company They wanted the revolution to enter like the ghost in Dickens’s Christmas Carol, with a flaming halo round its head and a big fire extinguisher under its arm.” Tocqueville’s Souvenirs (1893), cited by Namier, include his reminiscences of the 1848-1851 period, in which Tocqueville was himself a participant; his appreciation of the courage and desperation of the working-class actions in Paris is moving. In the same connection I should call attention to Edmund Wilson’s pioneering essay, “Flaubert’s Politics,” in The Triple Thinkers (1938). ↩

-

5

See Benjamin F. Bart, Flaubert (Syracuse University Press, 1967), $16.00, p. 639 passim. ↩