Derek Walcott is a poet, a playwright, a West Indian, sometime director of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop. For all I know, he may have other distinguishing marks, but these few are enough to give him a plot, a predicament. It is clear from the Overture to Dream on Monkey Mountain,* a collection of his plays, that he carries on his back a load of unfulfilled history, promises, promises. He has done well by his own promise, he has been as good as his word, but one man can’t do everything. When Mr. Walcott writes of Caribbean theater and its bearing upon the nature of Caribbean life, his prose reminds me of those early propaganda essays in which Yeats tried to call a theater into existence by will power and rhetoric. Often, what ought to be done requires magic, divine intervention. In the end, a writer settles for the inadequate resources of talent, time, energy, and a little patronage.

Mr. Walcott is a powerful writer, but many of his poems are trapped in the politics of feeling, knowing the representative fate they must sustain. It is enough for any poet that he is responsible for his own feeling: he answers to his scruple, his conscience, hard master. But Mr. Walcott’s poems try to serve a second master, the predicament of his people. They tie themselves in historical chains, and then try to break loose. It is my impression that the poems are trying now to escape from the politics of feeling by an increasingly personal understanding, taste, truth. Fighting against rhetoric, he resorts to rhetoric, both Caribbean, inescapable. Besides, he has a weakness for grandeur, and he rushes into temptation by writing of exile, ancestral loss, historical plangencies, the gulf between man and man.

He is in a middle state, history at one extreme, sensibility at the other; history, meaning loss and bondage, “customs and gods that are not born again,” and sensibility, meaning a sense of responsibility to feeling, its validity and measure. His chosen themes are black and white, Desdemona and Othello, “a life we never found,” ancestry, “I am the man my father loved and was,” New York, Robinson Crusoe, Christmas, death, Guevara, loneliness, leaving home and coming back. What these themes do to the sensibility is the substance of the book: in a word, exacerbation. Often the sensibility is outraged by fact, and the poem is a cry of humiliation.

In principle, Mr. Walcott wants a direct style. “All styles yearn to be plain / as life,” he says, but he will not let his own style yearn for that quality. In “Homage to Edward Thomas” he speaks of “lines which you once dismissed as tenuous / because they would not howl or overwhelm,” and in “The White Town” “the poet howling in vines of syntax,” is treated with irony. But many of Mr. Walcott’s poems howl, their sensibility overwhelmed. Sometimes the abuse is his own fault, one violence answering another, and we have the feeling that Mr. Walcott is impatient to assume the world, he will not wait for the just word. I find it surprising, for instance, that the word “prickling” appears so often in these poems: “eyes prickling with rage,” “hair / prickling the scalp.” Again:

Pins

of fine hair prickled his skin’s

horror of that cold.

It is hard to believe that the word is exactly right in each case. In diction, Mr. Walcott is striking, but often what he strikes is a hard bargain, practicing usury in the transaction between language and feeling. He writes everything so large that the reader is inclined to deduct something, to keep the situation reasonable. An impression of excess arises from Mr. Walcott’s poems, especially when they insist upon converting the natural forms into human terms:

From a harsh

shower, its gutters growled and gargled wash

past the Youth Centre.

And later:

I never tire of ocean’s quarrelling,

Its silence, its raw voice.

I, too, never tire of the ocean, but I would be disappointed to learn that those wonderfully alien sounds can so easily be translated into growling, gargling, and quarreling. If that is what the wild waves are saying, we are wasting our time listening to them. Mr. Walcott’s language does not give enough allowance to mystery or silence; he assumes that everything in nature can be overwhelmed.

Or most things, anyway. Some few are impenetrable: a concession wrung from Mr. Walcott when he encounters frosted glass. As for glass generally:

Elizabeth wrote once

that we make glass the image of our pain.

Mr. Walcott is extraordinarily resourceful with the image. In “A Village Life” it begins impenetrable:

But that stare, frozen,

a frosted pane in sunlight,

gives nothing back by letting no- thing in.

Later it justifies a corresponding attitude in the perceiver:

Advertisement

And since that winter I have learnt to gaze

on life indifferently as through a pane of glass.

In another poem the dirty window of a railway carriage is noted as if perception were already compromised. Scenes pictured from a train are “lantern slides clicking across / the window glazed by ocean air.” Near the end of the book, middle age brings the speaker “nearer the weak / vision thickening to a frosted pane.” My list is incomplete. I merely suggest that readers take the image as a point of entry to Mr. Walcott’s poems. Presumably it is related to the poet’s sense of himself as distinct, however marginally, from the mere sum of his experience.

As a poet, Mr. Walcott comes on strong: his common style is more suited to the theater, perhaps, and certainly the plays, especially The Sea at Dauphin and Dream on Monkey Mountain, seem native to their idiom. The finest poems are those in which Mr. Walcott’s sensibility communes with centuries of historical experience, the long perspective of life in place and time. Perhaps in these poems the venom of his own promises, needs, and aspirations is dispelled; there have been thousands of years before now. My favorite among such poems is “Air,” which starts from a paragraph in Froude’s The Bow of Ulysses almost as touching as the poem itself, then moves through a series of meditations, beautifully balanced, ending in a long sentence running down the page to the “nothing” at the end. It is a lovely poem, and there are other poems in the book almost as fine.

The Carrier of Ladders, W.S. Merwin’s new book, begins with poems about beginnings, implying rock bottom, starting out again. “Toward morning I dream of the first words / of books of voyages,” a few pages later, “Oh god of beginnings / immortal.” “The Piper” ends:

Beginning

I am here

please

be ready to teach me

I am almost ready to learn.

In the corresponding form of language, words are emptied of all allegiance except what remains in their cadence: that is, Mr. Merwin does by cadence what other poets do by image and figure, the further difference being that cadence is the last part of words to go and the best part to start from:

by now

more and more I remember

what isn’t so.

In these poems the diction is as tenuous as it can well be. The words do not call attention to themselves as words, they have hardly more than the modest aim of connectives, establishing rhythmic sequences on which later efforts depend. The poet is looking for ways, means, stirrings, directions (“oh long way to go”), guidance, consequence (“I do not think it goes all the way”), ultimately “the way home.” I was reminded of Theodore Roethke’s poems of beginning, his idiom of rudiments, as if words had to begin all over again, yielding up every position ostensibly reached. But Mr. Merwin’s version is more urbane than anything I recall in Roethke.

What distinguishes Mr. Merwin’s poems in this collection is the assumption that the mind may be imprudent to rely upon objects of perception. “Leaves understand flowers / well enough,” he says at one point; on the other hand, “the darkness is cold / because the stars do not believe in each other.” Objects are endorsed only when they are felt as participating in the life of feeling: “how many things come to one name / hoping to be fed.” As objects, independent of feeling, they are hardly recognized.

Just as words live so long as the cadence lasts and not a moment longer, so objects survive in our arbitrary sense of them. In these poems the body survives as footprints in snow, speech as the echo of speech, but the relation between man and nature is insecure, perhaps doomed. Many of the poems are soundtracks of loss and lapse: even on the page, with the finality of print, they look as if they have recently been divorced. When objects are invoked, they are seen in a middle distance, not as figures sturdy in their setting but as departing presences; losing their substance, they are diminished to their shapes.

So it comes as a shock when Mr. Merwin writes, as the last line of his “Third Psalm,” “oh objects come and talk with us while you can,” except that the note of desperation is true. We are to suppose a speaker of these poems, long accustomed to recitations of the beautiful, who is on the brink of discovering that beauty has nothing to do with truth. Those old books of voyages were “sure tellings,” but there is nothing now to tell. Mr. Merwin’s new poems issue from severance. They are not messages, swiftly delivered from poet to reader, but tokens of fracture; the only hope is to begin again with a recovered ABC of feeling.

Advertisement

I find these poems extremely moving. Of Mr. Merwin’s earlier work I have sometimes wondered why poems so richly endowed should not have passion as well. One poem led to another, and there was no wish on my part to give them up, but few of them stayed in the mind or cast a shadow beyond the page. I admired Mr. Merwin’s manner, not least his good manners, but I wished he would commit an outrage occasionally. The work seemed more impressive as poetry than as poems: that is, as evidence of a poetic imagination at large. The new book retains something of this impression: no single poems leap from it, but the book as a whole has an air of nobility which cannot be refuted.

I now think it vulgar to demand “passion” from such a poet as Mr. Merwin, if we mean something hieratic or Yeatsian. Mr. Merwin plays a different instrument, his fingering is different. “The First Darkness” begins:

Maybe he does not even have to exist

to exist in departures

then the first darkness falls.

Mr. Merwin’s special nuance of feeling is there, in his sense of existence in departure; as, later in the same poem, he speaks of stone as seen “though the eyes are not yet made that can see it.” Passion in the new book, if the word is to be used, is the energy of the book as a whole, the entire record of loss, fear, and hope; not a spirit to be distilled at any chosen moment, but a quality of conscientiousness which maintains itself throughout.

Mark Strand’s new volume, Darker, seems to me a much stronger work than his Reasons for Moving (1968) or Sleeping with One Eye Open (1964). The strength is largely the coherence of his figures. As the title claims, Mr. Strand is going deeper into the darkness, taking greater risks, but he is not foolhardy, he goes in well accoutered. His element is time; he has trained himself to walk in that darkness by practicing the tenses, seeing present things in the oblique light of the future, confronting present and past. He is very good on memory, but even better on prediction and the failures of prediction: best of all on situations in which it is possible to say, “the future is not what it used to be.”

Many of his poems sound as if they were written on the principle: take a cliché and wring its neck. For instance, that time changes us: in “The Remains” the poet goes through the motions of emptying his pockets, turning out his life, reciting events and coincidences, until at the end:

Time tells me what I am. I change and I am the same.

I empty myself of my life and my life remains.

In “The Prediction” the same imagination works upon future things, a young woman walking under the moon, and the future coming to her in a flash. But if Mr. Strand has a preference in these matters, it is given in the poem “Not Dying”: “The years change nothing.” At least that is what the speaker tells himself, perhaps because his need is great.

A poet engaged with time is likely to devise a structure against which he can play his temporal figures. He may not need anything as elaborate as a complete symbolism. Mr. Strand’s poems manage very well on a little system. Beginnings, hopes, and potentialities are featured as breath: “breath is what saves me.” In “My Life”:

Out of breath,

I will not rise again.

Whatever denies breath is given in static, visual terms: a map, and in one poem a black map of the present, representing finality, recognized too late to make a difference.

I am not sure how far such a modest system could go, but its success in the present book is clear. If it is stark, that is a venial fault, for it accords with the nature of Mr. Strand’s language. He likes to make his poems by putting down separate notations, bleak or triumphant in their finality. The design is not a network of relationships: it is the nature of each notation that it resists assimilation to the next, as if one item were separated from the other by a zone of silence. Often, in these poems, each line represents a distinct act of the mind, strict and superior. The syntax distinguishes one moment from the next, asserting its full stops. It may be that Mr. Strand admired this procedure first in Borges’s fiction, where the sentences offer themselves in single file with a show of independence. The lines have the precision of aphorisms: the fact that each is replaced by the next means that more precise notations are still possible rather than that an effect of intimacy and complication is sought.

Even in poems of praise, Mr. Strand favors the strict sentence. Like Christopher Smart in “Jubilate Agno,” he divides his poetic time into separate moments, a line to each. A line is never allowed to stain its neighbor. The form of the poem, as in Mr. Strand’s “From a Litany,” is the movement of feeling from one committed position to the next; the relation between the lines is definitive but not complex. The significance of any line consists in its weight rather than its anticipated involvement in other lines; when the involvement comes, the effect of strictness and commitment is retained. As in other litanies, the plot is simple, and the poetry comes with the detail, slight differences having disproportionately large effect.

The Country of a Thousand Years of Peace, James Merrill’s second book of poems, has been out of print for some time, and it is now resuscitated in an enlarged edition. Meanwhile Mr. Merrill has published Water Street (1962), Nights and Days (1966), and The Fire Screen (1969). Many of his poems start from an incident, a scene, a picture: a woman having a baby, a man washing his hands, a photograph, the mind’s eye view of Salomé. For the moment, the whole weight of human significance is deemed to concentrate upon the chosen place. The poet then sends his mind ranging about, circling over the place, wheeling as far as it cares to go, then returning, descending, until mind and place are reconciled.

The meditation is conducted with a certain inner gaiety, elegance, wit. The Salomé poem, for instance, proceeds so genially that doodling is turned into art, a kind of ball-point inspiration which appears effortless. Dreams lose their terror and become indistinguishable from perception. Mr. Merrill is “a sleuth of the oblique,” he delights in experiment and latitude, trying anything provided his taste allows it. If he carries his meditation lightly, the reason is that he is not intimidated by anything he knows of horror or boredom: whatever he knows, he can tackle. He has little time for time, if it offers itself as a gloomy topic, portentously overcast.

For him, the significance of life consists in extension, the wonderful fact that we have not exhausted the mind, though we threaten to exhaust ourselves. In a poem about the phoenix he speaks of the bird’s “flights between ardor and ashes, back and forth,” and it is clear that these are his own flights, too. Ashes are reality, the way things are, history, fact, gravity. Ardor is the mind’s possibility, passionate intelligence, wit for short. Flights may be long or short, a matter of choice. Mr. Merrill’s poems are flights of fancy or wit, as in “A Narrow Escape,” a variation on the theme of Eliot’s “Portrait of a Lady,” and a delightful poem in its own right. The book is hardly as daring as Nights and Days, but its “joyous memoranda” are exhilarating.

I wish I could find exhilaration in The Whispering Roots. The book is full of good will, good intentions, but it never gets off the ground. A certain charm resides in its competence; Mr. Day-Lewis can turn his hand to anything, a flair useful to poets laureate. A poet who can write a poem which includes the line, “I turn now to American university practice,” cannot be said to lack courage; such a man can be entrusted with the job of composing memorial verses on the death of Winston Churchill or T.S. Eliot. But competence is not enough.

The book begins with a series of poems on Ireland, the soil of Mr. Day-Lewis’s roots. But I am afraid these are picture postcard verses, nonetheless. An Anglo-Irish gentleman returns to native Ireland on a visit, looking for roots as another man might look for a good trout stream or an admired castle. He finds what he wants to find. “The modern age has passed this island by,” he reports: like hell it has, I report from a somewhat longer visit and a closer look. Mr. Day-Lewis sends postcards from Ballintubbert House, Avoca, Cleggan, Lissadell, the pony fair in Cliften, sundry places from which one says, “wish you were here.” But the poems, well-meaning, mean little, except that the poet is a bit nostalgic these days.

In the second and third parts of the book the themes are more general, and these suit the poet rather better than those of the first part, but the language is still dead. Mr. Day-Lewis’s style can only deal with facts by blurring them. In “Kilmainham Jail,” a poem about the martyrs of Ireland’s Easter Rising in 1916, he writes of these men:

Their dreams, coming full circle, had punctured upon

The violence that gave them breath and cut them loose.

Nothing is realized, nothing really apprehended: these words were possible, but they were not necessary. Nearly anything is possible. The trouble with such a language is that it betrays Mr. Day-Lewis into effects which he seems to have accepted for no better reason than that they offered themselves. “Epitaph for a Drug Addict,” for instance, seems to me a gross error of taste, but I cannot believe that Mr. Day-Lewis is tasteless. “Apollonian Figure” probably seemed a good idea at the time, but it now reads like a parody of Roy Campbell. As for “Moral,” where Mr. Day-Lewis produces a piece of uplift on the strength of an admirable sentiment from Whitehead, I am surprised that it passed the proof stage unrebuked.

The question of style is inescapable. It seems to me that Mr. Day-Lewis simply does not command a style of his own. What he does with Yeats’s style is therefore inevitable. It is probably imprudent of any poet to write another poem called “All Souls Night,” or another poem about Countess Markiewicz, unless he is determined to do better than Yeats in both cases. But it is folly to drag Yeats into an elegy on Churchill by writing

Soldier, historian,

Orator, artist—he

and then again by writing the following lines in a sequence on love:

When eyes go dark and bodies

One to another fly,

Let not the soul decry

What wisdom’s born from dialogues

Of wanton breast and thigh.

These poems cannot survive the style they mime.

Collecting Evidence is Hugh Seidman’s first book and a very good performance. He speaks of “a life at its end / in detached phrases,” and the interest of his poems is mainly a quality of their patience, waiting for the end. His official theme is “the old words: the old lives,” and while he insists that his poem is “a poem of absolute resignation,” he does not, in fact, resign. Sometimes his tone is rueful, sometimes exasperated, often he enters into complicity with the end, following the logic of a situation to its conclusion. But his heart is not in that place. “That Hamlet was more than his sickness” is one of many acknowledgements; the pillar stands, he says in another poem, “thru all humiliation and mischance.” There is also love: “what is there where love is not.” And art, and the love of art, “the possible / of construction,” fiction, the imagination, “the true museum / surrounding the one / they have built of concrete.” Mr. Seidman is collecting evidence to justify an apocalypse, but also to make the end a pity, when it comes.

Emptying the world, he is in some danger of filling it again and, worse or better still, filling it with the old things, people, feeling, affection, all the things that went wrong the first time. Gradually it emerges that this tough young poet, MIT scientist, is really an astrologer at heart, living by opposition, square, and trine. I began to suspect this charming poet of being a fellow-traveling archaic man and then, halfway through his book, found the suspicion confirmed. In one of his best poems, “The Days: Cycle,” a love story is told in a scientific context, “the jargon of acronyms & chance / encounters.” In the last stanza the speaker comes clean:

The ageless stars that hold us

by the force which is our own.

Not orthodox astrology, I admit, but close enough.

Further evidence would show that Mr. Seidman’s basic gesture, a sudden swerve from public to private truth, is a mark of his allegiance to the old gods:

Scientist of poetry

they’re burning Newark

and when she went away

I turned in my sleep

and the deepest synapse of my brain

sparked and broke.

Synapse, the dictionary says, is the junction, or structure at the junction, between two neurons or nerve cells. The little stanza is an anthology of junctions and disjunctions, beginnings and ends.

Finally Anne Waldman’s Baby Breakdown. I don’t know how to say this without offense, but I found the book a horrid little monster, a spoiled brat of a thing. Ted Berrigan, who wrote the blurb, makes only one statement with which I agree, that Miss Waldman “is no Emily Dickinson.” Apart from that, his eulogy means nothing to me and has no public relation to the poems.

It is perhaps significant that he refers to the poet as Anne; if he knows her personally, perhaps her poetry takes the form of action, words may not be her medium. On the mere evidence of the poems, Miss Waldman’s verses are baby-talk, precocious but not intelligent. The usual modish assumptions provide whatever content appears: the world was born today, young is by definition beautiful, a policeman is a billy club with a number, pot is good and acid is better, “give us your open mind.” Toward the end of the book the poems seem to tire of loving themselves and they think of something else, but the following passage is about as far as they go in that direction:

In fact at night

which is the best time

to be awake

if you enjoy

going slightly crazy

we don’t think too much

about the sky at all

Plotting the giant takeover

of the entire globe

occupies our total imagination now

Make no bones about it

We make love & dance

on the tired grave

of Thomas Jefferson

knowing he would

really dig it

if he could.

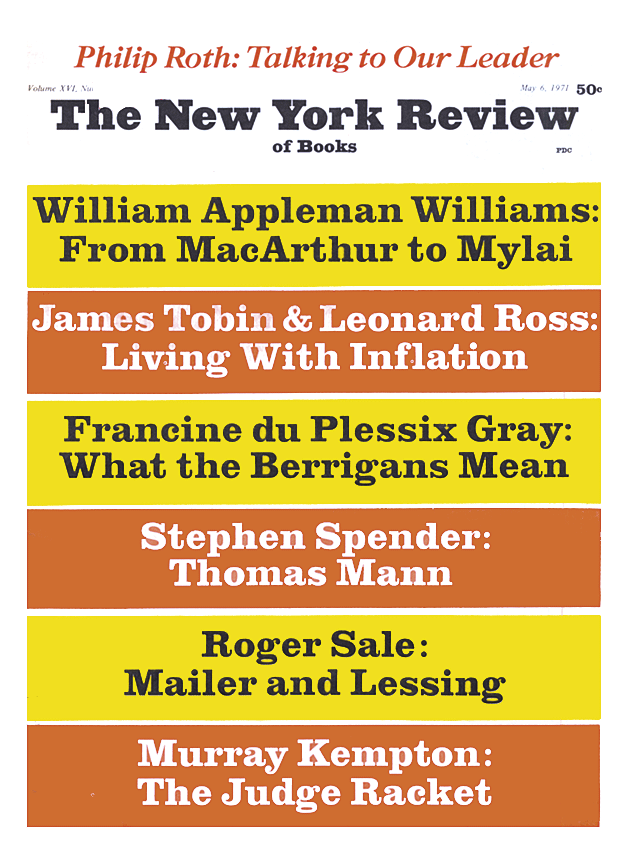

This Issue

May 6, 1971

-

*

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 326 pp., $10.00. ↩