Written Chinese is extremely difficult. Before the revolutions of the twentieth century, the literary language was a barrier protecting the Confucian elite. Anyone who could jump over that barrier by passing the official examinations immediately joined the ruling class. The strengths of written Chinese were its huge vocabulary and its enormous number of references and allusions. These could be mastered only by years of grinding study for which of course the poor had no facilities or leisure—though, as in America, the myth of equal opportunity was maintained by stressing a few extraordinary cases of poor boys reaching the top.

During the twentieth century radical intellectuals became aware of the stultifying and socially divisive effects of classical education. They deliberately tried to establish pai-hua, a demotic written language close to ordinary speech and accessible to all, through which they hoped to mobilize the people to strengthen China against foreign imperialism. However, the idea that good style consists of abstruse allusions has died extremely hard. The writer Lu Hsün, who devoted his life to rousing Chinese workers and peasants, is generally acknowledged to be the best writer in pai-hua. Even so his work is full of esoteric references which make his convoluted sentences difficult for many Chinese. Mao’s poetry is known to be traditional and refined; but much of his prose also contains classical images and phrases. Familiarity has made his writing easier to read and his style has influenced the spoken language.

The growing closeness of speech to writing makes it considerably easier to read works published after 1949. Nevertheless the esoteric tradition still flourishes. The Cultural Revolution began with an attack on a series of plays and articles written by a leading scholar, Wu Han, on an official in the Ming Dynasty called Hai Jui. In them Hai Jui was supposed to have championed the peasants against oppressive authority. Insiders knew that Hai Jui stood for P’eng Te-huai, the Minister of Defense who was dismissed in 1959 partly because he had criticized the Great Leap Forward. In 1950 Wu Han had talked with Mao Tse-tung about his position and that of other intellectuals under the new regime largely by referring to the career of a fourteenth-century Taoist monk.

To this esoteric tradition has been added the Soviet practice of indicating policies and positions in the hierarchy by subtle linguistic devices, the inclusion or omission of adjectives or the different ordering of formulae. This practice has been grafted easily onto another part of the esoteric tradition known as “praise and blame.” Confucius and later writers used this tradition to show approval or disapproval of historical figures by the way in which their names and titles were given. Thus in China today there is the paradox that articles and stories are written as simply as possible to reach and rouse the people, while at the same time the language of political infighting is deliberately allusive in order to keep the uninitiate from understanding it.

These are problems of communication for Chinese. For foreigners, particularly those studying Chinese history and culture, the situation is infinitely worse. In his fascinating annotated editions of Alice in Wonderland and The Hunting of the Snark, Martin Gardner referred to many works of scholarship and included hundreds of footnotes to explain Lewis Carroll’s work and convey some idea of his environment. The cultural distance between nineteenth-century Oxford and modern Anglo-American readers is relatively slight; nevertheless Mr. Gardner’s task was extremely difficult and he and his correspondents clearly missed many details. There is also the inherent problem of subjecting delicate works of art to crude scholarship.

But Martin Gardner’s presumption is nothing to that of Sinologists, who spend much of their time trampling over flower beds in order to point out familiar trees. To my knowledge no one in the West, for example, noticed the significance of Wu Han’s works on Hai Jui or of the many other esoteric satires published in the early 1960s; but to insiders they were obvious.

Why then should foreigners even attempt detailed studies of China? In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Jesuits and other Europeans approached China with respect. They tended to accept the current Chinese orthodoxy and tried to transmit its wisdom to the West. Sinology was created in the mid-nineteenth century in the full flush of positivism. All histories and cultures were to be reduced to scientific order. China’s civilization was to be made into an object fit for analysis. Ancient China, which had satisfactory academic similarities to the Western classical world, was much more suited to this treatment than more recent periods, where there was the problem of living Chinese.

However, in the latter half of the nineteenth century the conquest of the past was only a reflection of the conquest of the present. During this early but high stage of imperialism scholars found it necessary to believe that only white men were capable of “modern” activities. Thus what other people said about themselves might be interesting but it was “unscientific.” Accurate descriptions of other societies or histories had to be written by Europeans. By the turn of the century this position had to be modified when Sinologists came to realize the extremely high level—by Western standards—of Chinese textual and historical research. Nevertheless the earlier impetus and to some extent the racist beliefs behind it have persisted up to the present.

Advertisement

The obvious justification for research on China is that Western and Japanese studies are better than nothing. The Chinese comprise so large a part of mankind and their culture is so rich and well-recorded that one simply cannot neglect so important a part of human experience. Therefore any descriptions—however crude—are valuable. In the 1950s all kinds of scholarship flowered in China. Since then concern with the present has been so overwhelming that there has been relatively little new historical research there. Important source materials have been reprinted in Taiwan and the Chinese Diaspora, but original research has been hampered by lack of contact with China. This bleak situation is professionally providential for students outside China. In the West and Japan independent research provides a satisfying life and a prestigious occupation in a way that “mere translation” of Chinese secondary materials could never do.

There are, however, more decent justifications for outside study of China. Western and Japanese scholars study problems that interest them and presumably those around them. Thus their work can mediate between China and other countries in a way that Chinese writers with different preoccupations cannot. Another justification for cross-cultural studies is that although distance blurs details it gives a perspective that is sometimes interesting even to members of the culture being perceived. Professor Benjamin Schwartz points this out in his book on Yen Fu, the great Chinese translator of the early twentieth century. He argues that many of what most Westerners would consider to be Yen Fu’s misconceptions about the works he translated were in fact useful perceptions of the thought behind them. For instance Herbert Spencer believed himself to be an uncompromising internationalist, and is generally held to have been one. Yen Fu with his preoccupation on the weakness of China saw Spencer as an advocate of the release of human energy that would create strong nation states.

Professor Schwartz demonstrates that Yen Fu’s perception brings out real inconsistencies in Spencer’s thought: his proclaimed interest in the individual while being prepared to sacrifice any number of inferior individuals to the “natural” struggle for survival and the greater good of the whole. There was also his dubious but repeated analogy between society and a biological organism. If he had been consistent in applying this model he would have demanded that, just as cells or even limbs in advanced organisms are subordinated to central organs like the brain, individuals in highly developed societies should subordinate themselves to central control.

Professor Schwartz’s biography of Yen Fu is probably the most important cross-cultural study of ideas published in the last twenty years. It is not surprising that a brilliant and subtle scholar like Professor Schwartz should choose Yen Fu. Yen thrived on complexity and he was deliberately esoteric. He had no intention of popularizing his many important translations. He wrote in extraordinarily intricate classical Chinese because, as he said, “principles of original subtlety cannot be mixed together with language lacking in eloquence.” For this he was bitterly attacked by Hu Shih, one of the leading proponents of the pai-hua movement.

Hu Shih was by no means the first Chinese intellectual to write in the demotic language. He was however one of the first to abandon classical Chinese in all his work, even in his poems. He did not need the classical language, for he had a more up-to-date elitist defense, English. He spent seven years at Cornell and Columbia and remained enthusiastically pro-American throughout his life. He was particularly influential as part of the “loyal opposition” to Chiang Kai-shek, working with regimes that are often best seen as prototypes of neocolonialism. Thus in Hu’s case an American biographer has insights not available to a Chinese. These have been used well by Jerome Greider in Hu Shih and the Chinese Renaissance, which also contains fascinating descriptions of the intellectual arguments that took place in China in the 1920s and the 1930s. There is, however, something extremely dreary about Hu’s life as a bigoted pragmatist constantly telling students to work within the system and to deal with small concrete problems while Chinese society was visibly crumbling around him.

If Hu Shih was an American Chinese, the distinguished geologist Ting Wen-chiang was a British one. He was one of the very few Chinese who went not only to a university but also to school in the West. In many respects Ting remained a Chinese of his class, but the British stamp was deep and permanent. The paradox is not so great as it might appear. As his biographer Charlotte Furth rightly points out, there were profound similarities between the Confucian gentry and the ruling class of Edwardian England. Unlike the rest of his generation Ting was able to behave and think like a European. It is not surprising that Bertrand Russell wrote of him, “He was the ablest man I met in China.”

Advertisement

Ting was a scientist and contributed greatly to bringing Chinese geology up to high international standards. At almost the same time he became a businessman and held official posts under extremely corrupt warlords. In many respects he was a Chinese Fabian, an autocratic elitist reformer. He had an instinctive appreciation of authority and was a champion of law and order. Like the Webbs he admired Stalinist Russia while distrusting radicals at home. Charlotte Furth brings this out neatly in her excellent book.

The connection between Ting’s science and his politics fascinates her. In a famous literary debate on science and metaphysics he took the critical positivist view that science can know everything knowable. Society was clearly included. While China suffered the most appalling catastrophes Ting tirelessly argued that its problems should be solved scientifically. His message to the students was very much the same as Hu Shih’s: They should continue their study—to build up a new elite—and collect more data on social problems. Presumably with her own surroundings in mind Charlotte Furth stresses the conservative bias inherent in any attempt to apply “objective” social science. Defenders of the status quo can and do pretend to be “nonpolitical” because if let unstated their values will be assumed. Only radicals are obliged to create different ideologies and new values, thus defying “objective” science.

Yen, Hu, and Ting all had considerable experience of the West. There were very few like them. A far larger number of twentieth-century Chinese intellectuals gained their chief impression of the industrial world from Japan. For students of modern China Japan is fascinating and frustrating: fascinating as an alternative East Asian culture and a stimulating comparative case; frustrating to any studies of cultural relations between the West and China because it adds the further problem of the mediating effect of another culture. Western institutions and ideas transmitted to China appeared there in different forms, but in the early twentieth century nearly all of these passed through Japan. Thus it is far more difficult to trace the process of transformation, let alone analyze the reason for it.

A much more basic way in which Japan confuses Western students of China is simply that Japanese is another extremely hard language. Japanese scholars have produced and are producing thousands of books and articles on China. Many Western students of China have a smattering of Japanese, few have more. Thus to read an article in Japanese is an effort, a book often out of the question. Students in all fields of Chinese studies feel threatened by this mass of secondary material.

Kuo Mo-jo was among the many Chinese of his generation trained in Japan. He was married to a Japanese and spent long periods of his life there. In China, he is now president of the Chinese-Japanese Friendship Association. Yet the bibliography in David Roy’s biography contains only one entry in Japanese and that is peripheral. This is largely a matter of honesty. Where most writers would throw in the titles of a dozen virtually unread Japanese works, David Roy—a superb American scholar who has, I suspect, read twice as many books in Chinese as any of his contemporaries—refers only to works he has read or made use of. Another reason for the omission may be that Mr. Roy believes that Kuo’s life can be described in detail from his ample diaries, letters, and other autobiographical writings supplemented by pieces by his Chinese contemporaries.

Kuo is the Ilya Ehrenburg of the Chinese Revolution, or rather Ehrenburg is the Kuo Mo-jo of Russia, for Kuo’s intellectual and political career has had far greater influence. Both men came from rich and assimilated families of despised minorities, the Hakka and the Jews. Both began in the artistic rather than the political avant-garde, although the two worlds overlapped among Russian exiles in Paris and the Chinese both in Tokyo and in the foreign concessions in Shanghai. Both men romantically made the leap from romanticism to Marxism and both retained many of their earlier bourgeois sensibilities and prejudices. Both have written voluminously on many subjects, but especially about themselves. Their main similarity, however, is that both have been survivors.

Kuo was a poet who became a distinguished archaeologist and ancient historian. After 1949, he was the founder and chairman of the All China Federation of Artists and Writers, and later became president of the Academy of Sciences. At the same time he has held high political office. It is extraordinary for a polymath to be so successful without rousing enmities bitter enough to destroy him. That he survived the Cultural Revolution is still more remarkable. He made an early statement of self-criticism, saying that “if we are to judge by the standards of today all my works should be burned because of my failure to understand the thought of Mao Tse-tung.” As a passionate student of ancient China Kuo was an obvious target for the revolutionaries in their attacks on tradition. Many student groups were anxious to denounce him but the message always came down from above that he was to be left alone. In 1969, he was elected to the Party Central Committee and although he is now almost eighty he is still active as the president of the Academy of Sciences. When Peking bookshops a few weeks ago suddenly started selling major works unavailable since the Cultural Revolution, a book by Kuo Mo-jo was among them.

Clearly such an influential figure should have at least one Western biography. David Roy has begun this important task in Kuo Mo-jo: The Early Years, which will be essential reading for all students of modern China. Unlike the other works under review, it is more concerned with Kuo’s life and feelings than with his ideas. There is much to be said for this. The lives of most men—even intellectuals—often have more impact than their ideas. What is more, however intricate, subtle, and paradoxical the analysis of a man’s thought, it is bound to systematize what is essentially unsystematic. Nevertheless intellectuals are supposed to be interested in ideas, and among many academics there is a persistent feeling that it is indecently easy or unprofessional merely to study a man’s life.

There is, however, a positive aspect in refusing to deal with anything “lower” than the brain. Many Western students of China, particularly those influenced by Professor Schwartz, take what the men they study said and wrote very seriously instead of looking for hidden social or personal “determining” factors.

All the books mentioned above are products of the Harvard School of East Asian Studies established by Professor John K. Fairbank. There are now almost sixty titles in the Harvard series, which all maintain an extremely high standard of scholarship. Many are biographies or works that center on one man. One reason for this is that graduate students at the beginning of their research are faced with an abundance of immensely difficult Chinese historical material and by concentrating on one person they hope their study will gain coherence. But this is seldom easy in view of the shifts and transformations of a single life-time, and the number and variety of social, political, and intellectual lives one man can lead more or less simultaneously. It is also believed that four or five years spent working for a Ph.D. is a convenient period in which to cover the life of one person. This too can break down. Kuo Mo-jo, for instance, is far too wide ranging a figure and has lived too long to be dealt with in a scholarly way in one book. It is for this reason that David Roy’s useful book ends in 1924.

Biography is even more common among Chinese historians. Considered against the stereotyped view that the Chinese lack concern for the individual, interest in this personal literary and historical form is puzzling. But the earliest Chinese biographies served a specific social function. They seem to have been lives of ancestors recorded to cement clan and family unity. As in the West with its hagiography and lives of great men, biography in China was written for purposes that were more moral than historical. Lives are models for the young to follow. By far the most widespread literary historical form in China today is the life of the young dead hero. Traditionally there was a reluctance to write about “bad” men, and thousands of Chinese biographies and obituaries begin with passages showing how hard-working and brilliant the subject was as a child, and there is usually a section describing his extreme filial piety.

The earliest existing Chinese biographies are in the Shih-chi, Records of the Grand Historian, the comprehensive history written by Ssu-ma ch’ien in the second century B.C. Most of its chapters are constructed around the lives of great men and there is a large section specifically devoted to biographies; which is entitled Liehchuan, “connected traditions,” a name that reveals that the biographies were meant to be taken as a collection. Together they form one of the most memorable parts of the Shih-chi. Later historians largely adhered to the form established by Ssu-ma ch’ien; all of the twenty-four offical dynastic histories have a biographical section.

There were also many unofficial collections of obituaries, tomb inscriptions, and funerary odes; for the Ch’ing Dynasty (1644-1911) alone there are thirty-three important ones. During the 1930s a group of scholars condensed these into Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period. The work was directed by an American, Arthur Hummel, but was largely carried out by his Chinese collaborators. Its 800 biographies are examples of superb scholarship, and to find a fault in any of them gives one a glow of satisfaction that lasts for days. The biographies tend to concentrate—in a traditional Chinese way—on the subject’s official posts and esoteric literary works, but the collection also contains much social and political information on the elite. It is in many ways the best history of the Ch’ing period available in any language.

The success of Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period has attracted many imitators, and scholars in American universities are now completing similar projects on the Ming and Sung dynasties. Its influence on study of later periods has been even greater. In 1967, the first of four volumes of a Biographical Dictionary of Republican China was published under the direction of Professor Howard Boorman. Its 600 subjects were chosen for their eminence in the “Republican Period,” that is, between the fall of the Manchus in 1911 and the establishment of the People’s Republic. As Professor Boorman points out, this has resulted in an odd mixture of the living and the dead. Fewer references are given and the level of scholarship is not as high as that of Hummel’s work. Nevertheless the dictionary is an impressive achievement; it is, for example, more concerned with social and economic background than its predecessor.

One of the dictionary’s major faults is that it pulls its punches on the Kuomintang leaders. For instance, in the entries on Chiang Kai-shek and his wife’s family, the Soongs, there are no references to the notorious corruption of nationalist governments of the 1940s, let alone the Soongs’ central roles in it. The writers merely state that the communists “excoriated” T. V. Soong for using “official position for personal gain.” Or they write, “The image of the Soong family was at its best abroad,” a perfect example of their esoteric approach. Another flaw is that the dictionary tends to regard the period after 1949 as at best a sad twilight for scholars and intellectuals who stayed in China. The entry on the historian Ku Chieh-kang describes his “humble position as an annotator and punctuator” of a certain text; but Laurence Schneider points out in his fine biography of Ku that the “annotation” was an article in which Ku brilliantly summed up decades of study on the text and that in many ways during the 1950s his career was at its height.

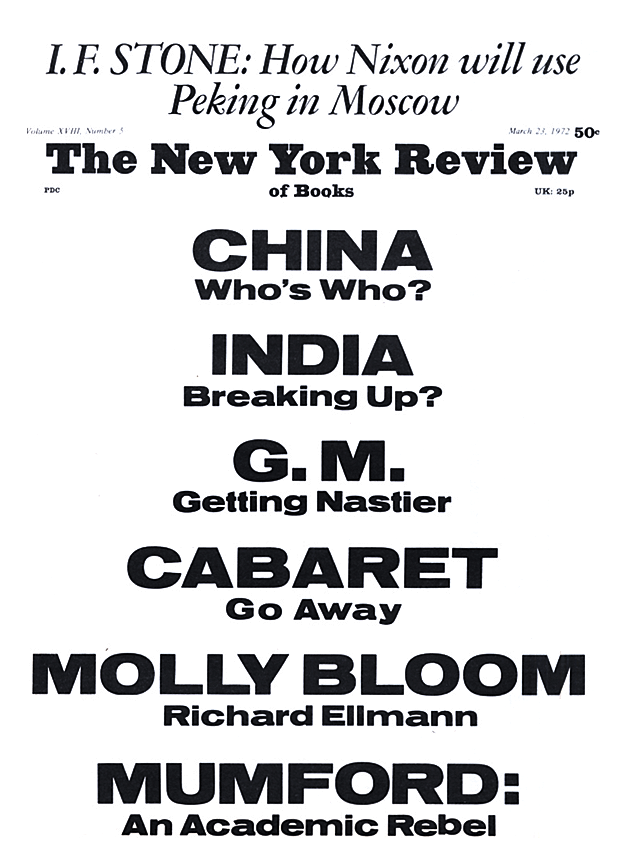

A still more recent successor to Hummel is the Biographic Dictionary of Chinese Communism 1921-1965. It is amazing that two editors, Donald Klein and Anne B. Clark, wrote 422 of its 433 entries. Both were on Professor Boorman’s staff and their own work shows his influence. Another tradition, however, is apparent in this dictionary. Throughout the twentieth century Westerners and Japanese have been publishing Who’s Whos in China for those doing business there. Most entries were merely lists of known appointments, but after 1949 this task became an official concern and the US government made large and expensive efforts to catalogue Chinese communists. Projects on which both Dr. Klein and Dr. Clark worked provided restricted information useful for espionage, but other more public work was also produced.

The American Union Research Institute has published a Who’s Who in Communist China. An enormous book, it deals with the careers of more than 2,800 men and women—the Japanese have exceeded even this with a dictionary containing over 12,000 names. These works are extremely useful for journalists and other China watchers who are encouraged to treat Chinese politics as a horse race in which “the favorite Chou En-lai is well ahead of the field but Chiang Ch’ing is moving up on the inside rail.” However the journalists are limited because their readers find it difficult to remember more than ten Chinese names at a time.

The lives in the Biographic Dictionary of Chinese Communism are in connected prose and go into far greater depth than do these works. Taken together they give a picture of the Chinese Communist movement that concentrates on the elite only but is nonetheless valuable. The pattern that emerges is extremely complicated. The only clear demarcations are those of sex and generation. Most of the leaders described are male and were born between 1890 and 1910. It is much more difficult to be precise about their class or geographical origin. All one can say is that they tend to come from rural areas, mainly in the central inland provinces, and are the sons of rich peasants or small landlords.

Before 1965 the stability of the Chinese leadership made it possible to hope that such a collection could function both as a history and as a tool for contemporary research. Any such hopes were dashed by the Cultural Revolution. It is ironic that just as American spies and scholars were beginning to understand the personalities and administration of Communist China, everything was thrown back into the pot. By January, 1972, most of the figures in the Biographic Dictionary appear to have fallen from power and to have been replaced by unknown outsiders.

An arbitrary list or racing form of the ten most powerful leaders in China could read: Mao Tse-tung, Chou En-lai, Yeh Chien-ying, Li Hsien-nien, Chiang Ch’ing, Yao Wen-yuan, Chang Ch’un-ch’iao, Chi Teng-k’uei, Chi P’eng-fei, and Wang Tung-hsing—the order given is also arbitrary and has no particular significance. In some cases their influence comes from their official positions. But at this moment of institutional flux, personal relationships often seem to be more important.

Naturally Mao and Chou are amply covered in both Boorman and Klein and Clark as are Yeh Chien-ying and Li Hsien-nien. Yeh, who is now seventy-three, comes from a rich Hakka family in Kwangtung. He had a formal military education and for twenty-five years he was a leading strategist of the revolution. In 1940 he became one of the ten Marshals of the People’s Liberation Army. Since 1940 he has held high official posts and traveled widely abroad. During the Cultural Revolution he rose still higher and unlike most other military leaders appears not to have been involved in the fall of Lin Piao.

Li Hsien-nien is extraordinary even in the generation of heroes produced by the Chinese Revolution. Coming from a poor peasant family he became an outstanding guerrilla leader. Without any higher education he became a superb administrator, economist, and expert in foreign affairs, in which capacities he has often been close to Chou En-lai. Li has been Minister of Finance since 1954.

Both dictionaries refer briefly to Chiang Ch’ing as Mao’s wife, but she and the other five “key” leaders do not have entries in either. However their names are listed in the excellent appendices at the end of Klein and Clark, which, as well as categorizing entries by age, regional origin, and education, give exhaustive lists of the members of different executives and committees. The six are also given very brief entries in Who’s Who in Communist China, none of which gives more than tantalizing hints about their careers or characters. Even if we add what we know from Japanese sources, our knowledge is still very slight.

Yao Wen-yuan, who is alleged to be Mao or Chiang Ch’ing’s son-in-law, is about forty-six, much younger than the other leaders. His father was a writer and he himself is a literary critic. He is an intellectual with a sharp mind and prose style. He first came to prominence as a very young man in the early Fifties when—with higher backing—he attacked a colleague of Hu Shih who had denied the political significance of the great seventeenth-century novel The Dream of the Red Chamber. At the end of 1965, Yao wrote the criticism of Wu Han’s writings on Hai Jui that launched the Cultural Revolution and he appears to have been a radical throughout that movement. In 1970 and the early part of 1971, during the eclipse and fall of Ch’en Po-ta, Mao’s secretary and champion of the rebels, Yao was expected to follow him. But by last summer he was back in public view, striking evidence that the Cultural Revolution is very unlikely to be renounced entirely.

Chang Ch’un-ch’iao, a member of the Politbureau, is vividly described in the brilliant Shanghai Journal by Neale Hunter.* His impression of Chang’s appearance on television was of a tough humorous man with a habit of turning aside in the middle of a sentence to light a cigarette. A journalist who later became an official in Shanghai, he rose to the top during the complicated struggle of the Cultural Revolution, with backing from Peking, by playing one faction off against another.

Chi P’eng-fei, the new Foreign Minister, has had a long and successful career in the ministry and in embassies abroad, including five years in East Germany.

Chi Teng-k’uei is about sixty. After holding various posts in the provinces he was appointed in 1968 to be vice chairman of the Honan Revolutionary Committee, from which Mao Tse-tung is supposed to have summoned him to Peking.

Wang Tung-hsing, who seems to be from Kiangsi province, has been head of Mao’s bodyguard and deputy head of the Bureau of Public Security for more than twenty years. Last summer he appears to have played an important part in factional fighting with Lin Piao.

It is of course far too early to know with any certainty what the economic and political differences were between the various groups in the leadership this summer and autumn. Probably one disagreement was simply that many army leaders who had possessed the only effective chain of command since the Cultural Revolution resented the reconstruction of the party and the government, especially since these had previously been tainted with revisionism.

Another much more tentative hypothesis is however fairly plausible on the scanty evidence available. This suggests that Lin Piao and many army leaders wanted to maintain China’s image of revolutionary purity and international isolation. To do this they appear to have pressed for major investment in the electronics industry which would back up national defense. At almost the same time, another group, probably including Mao and the “left,” advocated investment in the mechanization of agriculture to bring up the rural areas and to improve the political organization and consciousness of the peasants.

It seems plausible that Chou En-lai and other government leaders agreed to this radical policy with its consequent neglect of national defense only on condition that China could deal diplomatically to prevent an effective alliance between the four hostile forces surrounding her: the USSR to the north, Japan to the east, the US to the southeast, and India to the south. This would explain why both the government and the “left” should have agreed to respond to Kissinger’s blandishments. These were made more attractive by the realization that Nixon desperately needed the China trip to counter domestic opposition, and this was the best point at which to gain concessions from the US.

Army leaders seem to have objected to these policy changes, and some of them may even have disagreed with the new analysis that China’s principal enemy was the USSR rather than the US. Given the unpleasant choice between opening relations with America or easing them with Russia they may have preferred the latter. This would explain the mysterious destruction over Mongolia of a plane apparently heading for the Soviet border and carrying highranking Chinese officers. It is very unlikely but still possible that Lin Piao was on board. Now there is the still more fantastic story that Kissinger warned Chou En-lai of some dealings by Chinese army officers with Moscow. So many amazing events have taken place in China in the last six years that this nightmarish possibility cannot be ruled out entirely. No Western writer or biographer can adequately explain these events as yet. We must see the collected research on the lives of the recent Chinese leaders as the dim beginning of a quest for understanding that may never succeed.

This Issue

March 23, 1972

-

*

Prager, 1969. ↩