I sit looking out a window at 3:30 this February afternoon. I see a pasture, green out of season and sunlit; in an hour more or less, it will be black. John Berryman walks brightly out of my memory. We met at Princeton through Caroline Gordon, in 1944, the wane of the war. The moment was troubled; my wife, Jean Stafford, and I were introduced to the Berrymans for youth and diversion. I remember expected, probably false, images, the hospital-white tablecloth, the clear martinis, the green antiquing of an Ivy League college faculty club. What college? Not Princeton, but the less spruce Cambridge, England, John carried with him in his speech rhythms and dress. He had a casual intensity, the almost intimate mumble of a don. For life, he was to be a student, scholar, and teacher. I think he was almost the student-friend I’ve had, the one who was the student in essence. An indignant spirit was born in him; his life was a cruel fight to set it free. Is the word for him courage or generosity or loyalty? He had these. And he was always a performer, a prima donna; at first to those he scorned, later to everyone, except perhaps students, his family, and Saul Bellow.

From the first, John was humorous, learned, thrustingly vehement in liking…more adolescent than boyish. He and I preferred critics who were writers to critics who were not writers. We hated literary discussions animated by jealousy and pushed by caution. John’s own criticism, mostly spoken, had a poetry. Hyperenthusiasms made him a hot friend, and could also make him wearing to friends—one of his dearest, Delmore Schwartz, used to say no one had John’s loyalty, but you liked him to live in another city. John had fire then, but not the fire of Byron or Yevtushenko. He clung so keenly to Hopkins, Yeats, and Auden that their shadows paled him.

Later, the Berrymans (the first Berrymans, the first Lowells) stayed with us in Damariscotta Mills, Maine. Too many guests had accepted. We were inept and uncouth at getting the most out of the country; we didn’t own or drive a car. This gloomed and needled the guests. John was ease and light. We gossiped on the rocks of the millpond, baked things in shells on the sand, and drank, as was the appetite of our age, much less than now. John could quote with vibrance to all lengths, even prose, even late Shakespeare, to show me what could be done with disrupted and mended syntax. This was the start of his real style. At first he wrote with great brio bristles of clauses, all breaks and with little to break off from. Someone said this style was like Emily Dickinson’s mad dash punctuation without the words. I copied, and arrived at a manner that made even the verses I wrote for my cousins’ bouts rimés (with “floor,” “door,” “whore,” and “more” for the fixed rhymes) leaden and unintelligible. Nets so grandly knotted could only catch logs—our first harsh, inarticulate cry of truth.

My pilgrimage to Princeton with Randall Jarrell to have dinner with the Berrymans was not happy. Compared with other poets John was a prodigy; compared with Randall, a slow starter. Perpetrators of such mis-encounters usually confess their bewilderment that two talents with so much in common failed to jell. So much in common—both were slightly heretical disciples of Bernard Haggin, the music and record critic. But John jarred the evening by playing his own favorite recordings on an immense machine constructed and formerly used by Haggin. This didn’t animate things; they tried ballet. One liked Covent Garden, the other Danilova, Markova, and the latest New York Balanchine. Berryman unfolded leather photograph books of enlarged British ballerinas he had almost dated. Jarrell made cool, odd evaluations drawn from his forty, recent, consecutive nights of New York ballet. He hinted that the English dancers he had never seen were on a level with the Danes. I suffered more than the fighters, and lost authority by trying not to take sides.

Both poet-critics had just written definitive essay-reviews of my first book, Lord Weary’s Castle. To a myopic eye, they seemed to harmonize. So much the worse. Truth is in minute particulars; here, in the minutiae, nothing meshed. Earlier in the night, Berryman made the tactical mistake of complimenting Jarrell on his essay. This was accepted with a hurt, glib croak, “Oh thanks.” The flattery was not returned, not a muscle smiled. I realized that if the essays were to be written again…. On the horrible New Jersey midnight local to Pennsylvania Station, Randall analyzed John’s high, intense voice with surprise and coldness. “Why hasn’t anyone told him?” Randall had the same high, keyed-up voice he criticized. Soon he developed chills and fevers, ever more violent, and I took my suit-coat and covered him. He might have been a child. John, the host, the insulted one, recovered sooner. His admiration for Randall remained unsoured, but the dinner was never repeated.

Advertisement

Our trip a year later to Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital near Washington was softer, so soft I remember nothing except a surely misplaced image of John sitting on the floor hugging his knees, and asking with shining cheeks for Pound to sing an aria from his opera Villon. He saw nothing nutty about Pound, or maybe it was the opposite. Anyway his instincts were true—serene, ungrudging, buoyant. Few people, even modern poets, felt carefree and happy with Pound then…. When we came back to my room, I made the mistake of thinking that John was less interested in his new poems than in mine…. Another opera. Much later, in the ragged days of John’s first divorce, we went to the Met Opera Club, and had to borrow Robert Giroux’s dinner jacket and tails. I lost the toss and wore the tails. I see John dancing in the street shouting, “I don’t know you, Elizabeth wouldn’t know you, only your mother would.”

Pound, Jarrell, and Berryman had the same marvelous and maddening characteristic: they were self-centered and unselfish. This gave that breathless, commanding rush to their amusements and controversies—to Jarrell’s cool and glowing critical appreciations, to Berryman’s quotations and gossip. His taste for what he despised was infallible; but he could outrageously hero worship living and dead, most of all writers his own age. Few have died without his defiant, heroic dirge. I think he sees them rise from their graves like soldiers to answer him.

Jarrell’s death was the sadder. If it hadn’t happened, it wouldn’t have happened. He would be with me now, in full power, as far as one may at fifty. This might-have-been (it’s a frequent thought) stings my eyes. John, with pain and joy like his friend Dylan Thomas, almost won what he gambled for. He was more eccentric than Thomas, less the natural poet of natural force, yet had less need to be first actor. He grew older, drier, more toughly twisted into the varieties of experience.

I must say something of death and the extremist poets, as we are named in often prefunerary tributes. Except for Weldon Kees and Sylvia Plath, they lived as long as Shakespeare, outlived Wyatt, Baudelaire, and Hopkins, and long outlived the forever Romantics, those who really died young. John himself lived to the age of Beethoven, whom he celebrates in the most ambitious and perhaps finest of his late poems, a monument to his long love, unhampered expression, and subtle criticism. John died with fewer infirmities than Beethoven. The consolation somehow doesn’t wash. I feel the jagged gash with which my contemporaries died, with which we were to die. Were they killed, as standard radicals say, by our corrupted society? Was their success an aspect of their destruction? Were we uncomfortable epigoni of Frost, Pound, Eliot, Marianne Moore, etc.? This bitter possibility came to us at the moment of our arrival. Death comes sooner or later, these made it sooner.

I somehow smile, though a bit crookedly, when I think of John’s whole life, and even of the icy leap from the bridge to the hard ground. He was springy to the end, and on his feet. The cost of his career is shown by an anecdote he tells in one of the earlier Dream Songs—as a boy the sliding seat in his shell slipped as he was rowing a race, and he had to push back and forth bleeding his bottom on the runners, till the race was finished. The bravery is ignominious and screams. John kept rowing; maybe at the dock no one noticed the blood on his shorts—his injury wasn’t maiming. Going to one of his later Minnesota classes, he stumbled down the corridor, unhelped, though steadying himself step by step on the wall, then taught his allotted hour, and walked to the ambulance he had ordered certain he would die of a stroke while teaching. He was sick a few weeks, then returned to his old courses—as good as before.

The brighter side is in his hilarious, mocking stories, times with wives, children, and friends, and surely in some of the sprinted affairs he fabled. As he became more inspired and famous and drunk, more and more John Berryman, he became less good company and more a happening—slashing eloquence in undertones, amber tumblers of Bourbon, a stony pyramid talking down a rugful of admirers. His almost inhuman generosity sweetened this, but as the heart grew larger, the hide grew thicker. Is his work worth it to us? Of course; though the life of the ant is more to the ant than the health of his ant hill. He never stopped fighting and moving all his life; at first, expert and derivative, later the full output, more juice, more pages, more strange words on the page, more simplicity, more obscurity. I am afraid I mistook it for forcing, when he came into his own. No voice now or persona sticks in my ear as his. It is poignant, abrasive, anguished, humorous. A voice on the page, identifiable as my friend’s on the telephone, though lost now to mimicry. We should hear him read aloud. It is we who are labored and private, when he is smiling.

Advertisement

I met John last a year or so ago at Christmas in New York. He had been phoning poems and invitations to people at three in the morning, and I felt a weariness about seeing him. Since he had let me sleep uncalled, I guessed he felt numbness to me. We met one noon during the taxi strike at the Chelsea Hotel, dusty with donated, avant-garde constructs, and dismal with personal recollections, Bohemia, and the death of Thomas. There was no cheerful restaurant within walking distance, and the seven best bad ones were closed. We settled for the huge, varnished unwelcome of an empty cafeteria-bar. John addressed me with an awareness of his dignity, as if he were Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeth’s, emphatic without pertinence, then brownly inaudible.

His remarks seemed guarded, then softened into sounds that only he could understand or hear. At first John was ascetically hung over, at the end we were high without assurance, and speechless. I said, “When will I see you again?” meaning, in the next few days before I flew to England. John said, “Cal, I was thinking through lunch that I’ll never see you again.” I wondered how in the murk of our conversation I had hurt him, but he explained that his doctor had told him one more drunken binge would kill him. Choice? It is blighting to know that this fear was the beginning of eleven months of abstinence…half a year of prolific rebirth, then suicide.

I have written on most of Berryman’s earlier books. 77 Dream Songs are harder than most hard modern poetry, the succeeding poems in His Toy are as direct as a prose journal, as readable as poetry can be. This is a fulfillment, yet the 77 Songs may speak clearest, almost John’s whole truth. I misjudged them, and was rattled by their mannerisms. His last two books, Love & Fame and Delusions, etc., move. They may be slighter than the chronicle of dream songs, but they fill out the frame, alter their speech with age, and prepare for his death—they almost bury John’s love-child and ventriloquist’s doll, Henry. Love & Fame is profane and often in bad taste, the license of John’s old college dates recollected at fifty. The subjects may have been too inspiring and less a breaking of new ground than he knew; some wear his gayest cloth. Love & Fame ends with an intense long prayer sequence. Delusions is mostly sacred and begins with a prayer sequence.

Was riot or prayer delusion? Both were tried friends. The prayers are a Roman Catholic unbeliever’s, seesawing from sin to piety, from blasphemous affirmation to devoted anguish. Their trouble is not the dark Hopkins discovered in himself and invented. This is a traditionally Catholic situation, the Sagesse, the wisdom of the sinner, Verlaine in jail. Berryman became one of the few religious poets, yet it isn’t my favorite side, and I will end with two personal quotations. The first is humorous, a shadow portrait:

…My marvelous black new brim- rolled felt is both stuffy and raffish.

I hit my summit with it, in firelight.

Maybe I only got a Yuletide tie

(increasing sixty) & some writing paperbut ha(haha) I’ve bought myself a hat!

Plus strokes from position zero!

The second is soberly prophetic and goes back twenty-six years to when John was visiting Richard Blackmur a few days before or after he visited me:

Understanding

He was reading late, at Richard’s down in Maine,

aged 32? Richard and Helen long in bed,

my good wife long in bed.

All I had to do was strip & get in my bed,

putting the marker in the book, and sleep,

& wake to a hot breakfast.Off the coast was an island, P’tit Manaan,

the bluff from Richard’s lawn was almost sheet.

A chill at four o’clock.

It only takes a few minutes to make a man.

A concentration upon now and here.

Suddenly, unlike Bach,& horribly, unlike Bach, it occurred to me

that one night instead of warm pajamas,

I’d take off all my clothes

& cross the damp cold lawn & totter down the bluff

into the terrible water & walk forever

under it out toward the island.

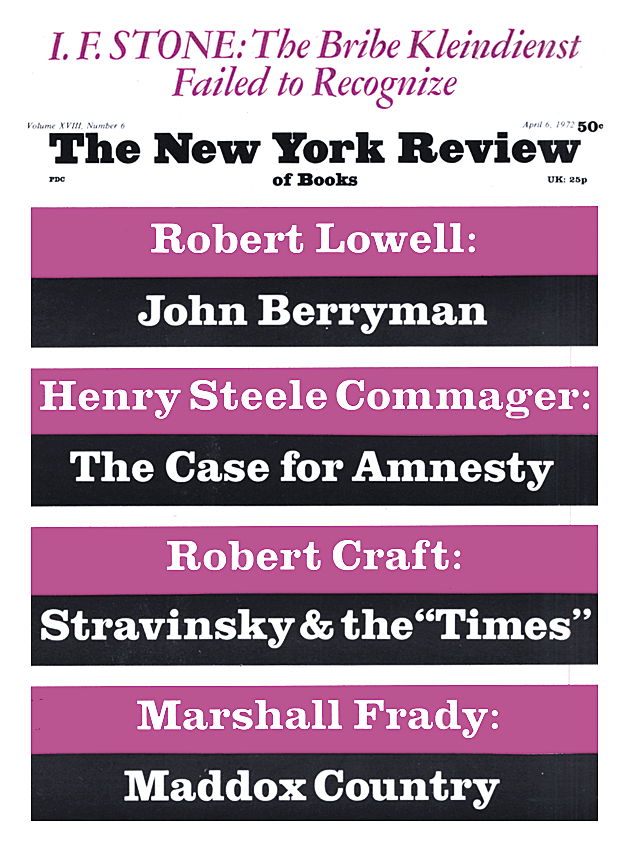

This Issue

April 6, 1972