According to Alain Touraine: “A new type of society is now being formed. These new societies can be labeled post-industrial to stress how different they are from the industrial societies that preceded them…. They may also be called technocratic because of the power that dominates them. Or one can call them programmed societies to define them according to the nature of their production methods and economic organization.”1

This description does not differ widely from those which have been formulated by a number of other writers. Brzezinski, for example, has observed that “America is in the midst of a transition that is both unique and baffling…ceasing to be an industrial society, it is being shaped to an ever increasing extent by technology and electronics, and thus becoming the first technetronic society“;2 while Daniel Bell, in his “Notes on the Post-Industrial Society,”3 emphasizes the central importance of theoretical knowledge in the system of production, and the shift from a manufacturing economy to a service economy.

But if the initial descriptions of the new society are similar, the interpretations of its historical character and potentialities are not. Brzezinski and Bell conceive it as a society in which major social divisions have been largely overcome,4 the domination of technically competent elites is more or less widely accepted, and the general course of social development is determined by a relatively harmonious process of economic growth. In such a society, it is claimed, there will be no basis for widespread dissent:

…it seems unlikely that a unifying ideology of political action, capable of mobilizing large-scale loyalty, can emerge in the manner that Marxism arose in response to the industrial era…. The largely humanist-oriented, occasionally ideologically minded intellectual dissenter, who saw his role largely in terms of proferring social critiques, is rapidly being displaced either by experts and specialists, who become involved in special governmental undertakings, or by the generalists—integrators, who become in effect house ideologues for those in power, providing overall intellectual integration for disparate actions.5

Touraine’s view is entirely different. The social conflict between capital and labor, he suggests, is losing its central importance in the capitalist societies of the late twentieth century, but new forms of domination (which are to be seen also in the state socialist societies) are giving rise to new social conflicts—between those who control the institutions of economic and political decision-making and those who have been reduced to a condition of “dependent participation.”6 The new dominant class is no longer defined by property ownership, but by “knowledge and a certain level of education.” The revolt against it arises from the will of the dependent class to break away from its dependence and to embark upon an autonomous development. Touraine supports this idea of the changing nature of social conflict by referring to the growth of new social movements, especially those that took a prominent part in the revolt of May, 1968, in France:

One of the significant aspects of the May Movement is that it demonstrated that sensibility to the new themes of social conflict was not most pronounced in the most highly organized sectors of the working class. The railroad workers, dockers, and miners were not the ones who most clearly grasped its most radical objectives. The most radical and creative movements appeared in the economically advanced groups, the research agencies, the technicians with skills but no authority, and, of course, in the university community. [P. 18]

This is not a reversion, he observes, “to meaningless themes like the end of the working class.” It is plain that “no socio-political movement of any strength can develop unless it includes the laboring class, which contains the greatest number of dependent workers.” The question is a different one: whether the working class can be conceived any longer, in Marxist terms, as the principal animator of social conflicts and the privileged agent of historical change. Touraine, basing his analysis mainly upon the social movements and conflicts of the 1960s, argues that it cannot:

In modern societies a class movement manifests itself by direct political struggle and by the rejection of alienation: by revolt against a system of integration and manipulation. What is essential is the greater emphasis on political and cultural rather than economic action. This is the great difference from the labor movement, formed in opposition to liberal capitalism. Such movements are scarcely yet beginning but they always talk about power rather than about salaries, employment or property. [P. 74].

Touraine associates with the emergence of these new social conflicts the development of an intellectual confrontation between two kinds of sociology. On one side the “sociology of decision” is concerned with the management of social tensions, adaptation, and the reconciliation of dissenting groups. It is the sociology practiced by Brzezinski’s “experts” and “house ideologues,” who serve the new rulers of society. On the other side is the “sociology of opposition,” which seeks to interpret the significance, the tendencies and aims, of those social movements which are in conflict with the existing society. Touraine emphasizes that these are two sociologies, which must “struggle for an explanation of the facts,” not confine themselves “within self-righteousness and the repetition of ideology.” A sociology of opposition only becomes possible when there are facts to be explained, when society begins to react to its own changes, defines new objectives, and experiences “the social and cultural conflicts through which the direction of the changes and the form of the new society may be debated.”

Advertisement

This attempt—made in the particular context of French society—to discern the social basis of the new radicalism, to furnish it with a theory of society, and to define its relationship with the labor movement and with Marxism, has its counterparts elsewhere: in Germany, in what is known as “critical theory,” and in the English-speaking world, rather less incisively, in various prolegomena to a “critical sociology.” Albrecht Wellmer’s book provides a useful, though not easy, introduction to “critical theory.” His exposition takes in three interwoven themes: first, the development of ideas within the Frankfurt school of sociology, from the writings of Horkheimer in the 1930s to those of Habermas in the late 1960s; secondly, the connection between this development and the changes in the socio-economic structure of Western capitalist societies; thirdly, the differentiation of “critical theory” from mere interpretation of social events on one side and from Marxism on the other.

What then is the “critical theory” of the Frankfurt school? Some of the leading ideas of this school were expounded by Horkheimer in a series of articles published in the mid-1930s7 upon which Wellmer draws for much of his discussion. The Frankfurt sociologists and philosophers regarded their theoretical work as part of the revolutionary struggle which was being waged by the proletariat against capitalism. Because of the circumstances of the time—the economic breakdown of capitalism and the pre-eminent role of the working-class movement (notwithstanding its defeat in Germany and the extent of the internal divisions between communists, social democrats, and anarchists) in the opposition to fascism—the main object of their theoretical criticism was, as for Marx himself, political economy. That is to say, they were engaged in an analysis of the economic contradictions of capitalism which would have made possible a revolutionary struggle for socialism.

Even at this time, however, Horkheimer introduced another element into critical theory. Although only the proletariat could discover in critical theory the self-consciousness of its political struggle, it would not necessarily do so; the situation of the proletariat is no “guarantee of true knowledge.” The revolution will only be brought about by the conscious will of the masses if there is a successful “process of anticipation of a rational society,” both in thought and in the organization of the working-class movement.

This idea, that the attainment of socialism depends upon the formation of an intention to create a liberated, rational society—an intention which has to take practical shape in mass organizations—became increasingly important in critical theory when the work of the Frankfurt school was renewed after 1945, and it led to a displacement of attention from the “economic contradictions” to the political and cultural apparatus of modern capitalism. This reorientation was in part a reaction against the Stalinist version of Marxism, in which socialism was reduced to an expression designating the form of society which emerged more or less mechanically from an economic transformation accomplished under the leadership of a Communist Party; but it was also a response to the changed social position of the working class as it experienced “the benefits of a regenerated, state-interventionist capitalism.”

Wellmer gives particular attention to the first of these influences, in a chapter on the “latent positivism of Marx’s philosophy of history.” This “positivism” he discovers in Marx’s conception of a “natural science” of human history, in which human activity, the self-creation of man, is comprehended only as labor, as the production of objects. The succession of different systems of production, including the transition to a classless society, is seen as a necessary, determined process. Although Marx also expressed (especially in his early writings) a different notion of activity, as human interaction or praxis,8 the positivist conception, according to Wellmer, predominates in Marx’s own thought and in later Marxism. It can be formulated as the assumption that “the irresistible advance of technical progress, which starts with the capitalist mode of production, has to be interpreted as the irresistible advance towards the commonwealth of freedom” (p. 73). This, Wellmer argues, “provides the starting point for an erroneously technocratic interpretation of history, which was to become a practical reality in the hands of the omniscient administrators of historical necessity” (p. 69).

Advertisement

The extent to which critical theory has now diverged from Marxism can be seen from Wellmer’s conclusion:

Since history itself has thoroughly discredited all hopes of an economically grounded “mechanism” of emancipation, it is not only necessary for a theoretical analysis to take into account entirely new constellations of “bases” and “superstructures”; in fact, the criticism and alteration of the “superstructure” have a new and decisive importance for the movements of liberation. In order to reformulate Marx’s supposition about the prerequisites for a successful revolution in the case of the capitalist countries, it would be necessary to include socialist democracy, socialist justice, socialist ethics and a “socialist consciousness” among the components of a socialist society to be “incubated” within the womb of a capitalist order. [Pp. 121-2]

He goes on to argue, finally, that Marx’s concept of class has largely lost its utility as an instrument of analysis, and that because science has become the “form of life” of industrial societies, enlightenment is only possible as an enlightenment of those who participate directly or indirectly in science. Thus the opposition between “critical” and “traditional” thought can no longer be interpreted in purely political terms as the expression of a class conflict, but must be settled on the ground of science itself—or in other words, mainly in the universities.

This latest form of critical theory seems to resolve the struggle for a new society into a purely intellectual contest. It is very unlike Touraine’s theory, which, although it begins from similar ideas about the role of science in production and the diminishing importance of the conflict between bourgeoisie and proletariat, conceives the antagonisms in the post-industrial societies as political struggles between new social classes. Touraine emphasizes the historical continuity in social movements and ideologies, and recognizes that the working class is still, despite its changed conditions of life, a vital element in any radical movement.

But critical theory, in Wellmer’s version of it, appears to make a clear break with the past and to separate itself as completely as possible from the traditional labor movement. The dangers inherent in such an outlook are obvious. Critical theory may become confined within a narrow intellectual milieu as a defiant, arrogant, but despairing criticism of a world in which the very desire for liberation is being extinguished, and which the critic is powerless to change. Indeed, this is the character that it assumed in Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man. As Wellmer himself notes, critical theory, in its later development by Adorno, Horkheimer, and Marcuse, “conceives itself as a protest, but as a protest impotent in practice.”

Only the growth of a radical student movement overcame for a time the tendency toward pessimism and withdrawal in Marcuse’s work; but this movement itself has proved too limited, too uncertain, to provide the nucleus of a force that could really change society. Wellmer, who is unwilling to accept the sterile opposition between the enlightened critic and a benighted world, tries to resolve the problem by assigning to critical social theory the task of showing “the contradiction between society as it is, and what it could be and must be in terms of its technical possibilities and of the interpretations of the ‘good life’ acknowledged within it.” The eventual test of the theory, then, would be that large numbers of people came to see this contradiction and entered upon a struggle to achieve the “good life” as they understood it, in opposition to what now exists.

This is reminiscent of Marx’s declaration (in 1843) that “we develop new principles for the world out of its existing principles…we show the true nature of its struggles…and explain its own actions.” What is lacking is any equivalent of Marx’s subsequent discovery of the proletariat; that is to say, the identification of actual social groups, already engaged in diverse conflicts, whose actions can plausibly be interpreted as developing into a general rejection of the existing form of society and an attempt to create a new social order. From this point of view, the philosophical discussion pursued by Wellmer is inconclusive, and even misleading in so far as it turns the whole question into a matter of scientific debate, and it needs to be extended into the kind of sociological inquiry that Touraine undertakes.

What is common to the work of Wellmer and Touraine is the effort to construct a post-Marxist theory of post-industrial society. Norman Birnbaum, in his volume of essays (as in his earlier book The Crisis of Industrial Society), undertakes in a more tentative fashion an analysis of the changes in industrial societies, and a critical appraisal of the attempts to comprehend them. His general outlook is well conveyed in the essay on “late capitalism in the United States,” where he writes: “What we face is a situation of genuine historical indeterminacy…. Our situation is…not unlike that of the first generation of Marxists in the face of new historical forces.” What Birnbaum is saying is that neither he nor anyone else has yet been able to define in a convincing way the social forces that “determine” political developments in American society; and to take one crucial example, the forces that shape American foreign policy and the opposition to it.

In one of the best of these essays he subjects Marxism to a critical analysis in which its principal inadequacies are clearly set out: the difficulties with the notions of class and class conflict in the societies of the late twentieth century; the failure to analyze political power in any other way than by asserting its direct dependence upon the situation of social classes; the neglect of cultural changes and their possible consequences in political life.

Elsewhere, Birnbaum examines some of the ideas and interpretations which have been formulated either as revisions of the Marxist theory or as alternatives to it, and shows himself to be just as severe a critic of these new theoretical schemes as he is of the more orthodox and dogmatic versions of Marxism itself. Concluding a brief review of writing on the “post-industrial revolution,” he remarks that this notion “cannot be used in serious discussion unless those utilizing it are prepared to do the rigorous work of specifying precisely the social forces at work, their direction, and their consequences for the future of industrial societies” (p. 414). (This, however, is exactly what Touraine has undertaken.) Earlier in the same essay Birnbaum affirms the continuing importance of the concentration of property ownership, against the view that the industrial societies are now dominated by a technocratic elite. But at the same time he recognizes that a technocratic or “knowledge” elite which does not own property is a significant new phenomenon in these societies.

In what way, then, do these essays disclose a movement “toward a critical sociology”? Certainly they offer a broad and often penetrating criticism of many current interpretations of the changes that are going on in the industrial countries (for example, in Birnbaum’s dissection of Roszak’s idea of the counterculture). They help to reveal the full extent of the disagreements and uncertainties among radical thinkers. But they do not attempt to formulate an alternative “critical theory.” Such self-denial may have a justification. If our historical situation really has the indeterminacy that Birnbaum attributes to it, then critical thought, however much it is inspired by the aim of bringing about a liberated society, is likely to reflect, and should reflect, this state of affairs in its own tentative and exploratory character.

However, one of the intellectual disagreements in the radical movement concerns precisely the extent to which our situation is indeterminate, and the future indecipherable. The differences in outlook between Wellmer and Touraine on one side and Birnbaum on the other seem to arise in part from differences in the social environments in which they are active. In France and Germany the social critic forms his ideas within the socialist labor movement and an influential tradition of Marxist thought. Changes in the character of the working class (and more generally in the class structure), and the problems that arise within Marxism in attempting to comprehend these changes, may lead him to a revision of Marxism or to the elaboration of a new theory which builds upon Marxism. But this work of criticism, and the renewal of ideas, takes place in a milieu in which there are still large and active social movements engaged in a political struggle for a socialist society.

In the US the absence of a socialist labor movement, and of any substantial body of Marxist thought, means that the social situation has been indeterminate, from the point of view of a radical thinker, for some time, and the present uncertainties repeat, in large measure, those which appeared at earlier times in this century. This characteristic is recognized, in a particularly constructive way, in a recent essay by Richard Flacks9 based upon discussions among a group of radical social scientists. Flacks suggests that in order to stimulate the kind of intellectual work that would help to bring about a social transformation it is useful to define the objective in the following way: “Let us imagine that an organized socialist movement or party existed in the US, what kinds of things would sociologists do who were allied to it?”

Starting from this supposition he outlines the major problems, some theoretical, but most of them empirical, which would form the subject matter of a critical sociology. The problems are broadly similar to those upon which Touraine concentrates his analysis—the potentialities of a post-industrial society seen from a socialist perspective, and the question of the possible agents of change, of the ways in which the new social groups of educated workers, technicians, administrators may develop a radical outlook and radical political action.

Thus Flacks sets out as problems for inquiry such issues as the following (which I have taken from different sections of his paper and paraphrased): To what extent could existing technology eliminate routinized human labor? What are the political, economic, cultural, and social barriers to such a development under capitalism? Is post-industrialism possible within one country; can “post-scarcity” be achieved without imperialism? How far are Americans (and which Americans) prepared to trade certain kinds of possessions and commodities for reduced labor, improved natural and urban environments, a richer community life, education, health, and other social services? What evidence is there of a new working-class consciousness (among educated workers, for instance)? What are the main sources of support for and resistance to the existing movements for radical change?

The eventual test of any “critical theory” or “sociology of opposition” can only be the development, or failure to develop, of large-scale social movements which aim to create, and begin to create in practice, an egalitarian, noncoercive form of social life. In the meantime the theory remains hypothetical. What justifies its existence at present, and makes such theoretical inquiry worthwhile, is the potentiality that has been revealed in the labor movement and in the new social movements of the past decade for a renewed activity to transform society.

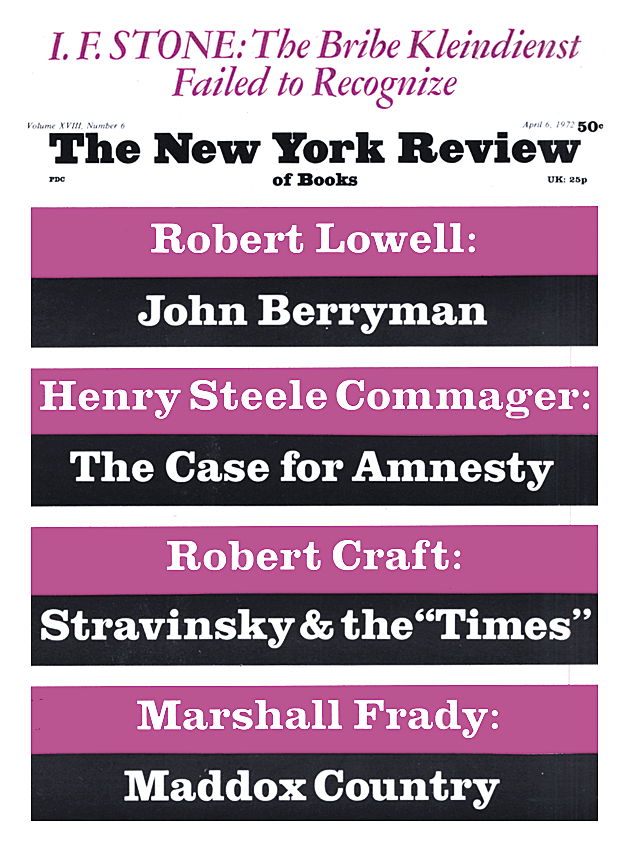

This Issue

April 6, 1972

-

1

The Post-Industrial Society, p. 3 ↩

-

2

Zbigniew Brzezinski, “The American Transition,” New Republic 157 (December 23, 1967), pp. 18-21; reprinted in Information Technology in a Democracy, edited by Alan F. Westin (Harvard University Press, 1971), pp. 161-7. ↩

-

3

The Public Interest 6 and 7 (Winter, 1967, and Spring, 1967), pp. 24-35 and 102-118. ↩

-

4

The same idea is expressed by Raymond Aron in several of his writings on modern industrial society, especially in Progress and Disillusion (1968), p. 15, “ experience in most of the developed countries suggests that semi-peaceful competition among social groupings is gradually taking the place of the so-called deadly struggle in which one class was assumed to eliminate the other.” ↩

-

5

Brzezinski, “The American Transition.” ↩

-

6

“Dependent participation,” or alienation, exists when “a man’s only relationship to the social and cultural directions of his society is the one the ruling class accords him as compatible with the maintenance of its own domination . Ours is a society of alienation, not because it reduces people to misery or because it imposes police restriction, but because it seduces, manipulates and enforces conformism” (p. 9). ↩

-

7

They appeared originally in the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung and have now been collected in Max Horkheimer, Kritische Theorie der Gesellschaft (2 vols., Frankfurt, 1968). ↩

-

8

See the discussion in Jürgen Habermas, Knowledge and Interests (London, 1971). ↩

-

9

Richard Flacks, “Towards a Socialist Sociology: Some Proposals for Work in the Coming Period,” The Insurgent Sociologist II (2), Spring, 1972. ↩