Beryl Bainbridge is possibly the least known of the contemporary English novelists who are worth knowing. She has written four very interesting novels, the fourth and last of which, The Dressmaker, also deserves to be called a triumphant success. But she has, as yet, only the beginnings of a reputation in Britain, and has next to none, so far as I can judge, in America, where the last but one, Harriet Said, appeared in the autumn of last year.

It turns out that the last but one of her novels was, in fact, written first, and was submitted to London publishers in the late Fifties. One of them wrote to inform her that the two girls who are its leading characters were “repulsive beyond belief,” and that one of the scenes was “too indecent and unpleasant even for these lax days.” He went on: “I fear that even now a respectable printer would not print it.” The manuscript then got lost in the cupboards of some publishing house. Now that it has been recovered and published, it is apparent that, even by the standards of the vigilant late Fifties, it was inane to talk of unpleasantness and indecency.

In the meantime, two subsequent novels, A Weekend with Claud and Another Part of the Wood, had come out: in view of what had happened to the first, it must have taken courage to persevere with them. Both are badly under-edited, and the second is rife with misprints. Beryl Bainbridge’s publishing history is perhaps the kind of thing you’d expect of a writer who is preoccupied with the idea of isolation, and who is described on one of her dust jackets as “something of a recluse.” It may be that this portrayer of shyness and constraint, who appears to be no punctuator, found it difficult to cope with the embarrassments of a debut, and of getting herself properly published. On the other hand, she could not have been the easiest of talents to respond to, and her first publisher should be praised for doing so, despite the editorial slackness that was shown. This is far from uncommon in English publishing, which has fallen upon lax days in more respects than one.

She may well have found it less of a strain to manage her debut as an actress. She comes from Liverpool, and for a while she acted there and in London, where she now lives. More than any other place, it is Liverpool that she writes about. This Victorian metropolis and port, which is still going rank and strong and loud and clear, has given her much to ponder, and her mind continues to frequent the streets around the cathedral. Not long ago she wrote a piece about her native city, and about her father, which indicates that her family went up in the world, becoming more “respectable,” but that it retained a keen awareness of working-class life. The piece imparts her father’s opinion to the effect that the famous intimacies of the type of working-class life which revolves around kinship cannot hope to cure the friendlessness of the individual human being, and it offers an insight into her favorite themes of isolation, and of loss and departure.

My father was surrounded from birth by monumental edifices to trade and commerce. He wasn’t an educated man, but he had a lot of theories. He said there was an illusion, fostered from infancy to the grave, that man wasn’t alone. First, he said, there was the parasite growth, jelly wrapped in Mother’s womb, and then the woolly blanket days of babyhood with all the family pressing close—aunties and cousins, brothers and sisters, the people living in the street. A whole army of relations keeping out the loneliness. Gradually, the ranks grew thin, the brothers and sisters fell out of line, the cousins deserted, the mothers and fathers started to die. To be replaced by reinforcements from other regiments—sweethearts, wives, the lost love, the unrequited soul-mate, sons and daughters of one’s own. Even the dog purchased for the children fulfilled its function. When they left, the dog lived on. From its jaws came a smell like rotting leaves. But when death came for you, the illusion was exposed. Though the room be filled with people, you were alone and no one was going with you. What remained, he said, when the man died, when his furniture and bits of paper had been dispersed, when his blankets had been sent to the bagwash to be passed on to someone worthy, were the bricks and mortar of his dwelling-place, the space he had inhabited. Buildings stayed put. They endured.

But now Liverpool has been redeveloped, and many of the old buildings have been demolished:

It’s easy to be nostalgic about the past when you were never less than middle-class. We lived outside the city on the coast. We had a Wolseley car with a card-table in the back. But my father was poor when he was young, and if he’d lived he wouldn’t understand the desolation and the no man’s land: all his memories torn down—the house he was born in, the madhouse where his Granddad died, the brewery where his brother worked.

The article ends:

Advertisement

He was very fond of playing a game called Departures. He was skittish when I was a child. He would take me down to the pierhead and put me on the ferry boat to New Brighton. I would stand on the deck of the Royal Daffodil and watch him dwindling on the landing-stage. Sometimes he waved his pocket handkerchief, and sometimes he raised his homburg hat in a last emigration gesture of farewell.

He was a bigoted man, my father, but he had a point about the buildings.

I think that he did have a point. At the same time, it could be objected that his faith was misplaced: buildings and kin have been swept away in the same flux. This enables one to recognize that Beryl Bainbridge’s books are commemorative. They are an attempt to save something from that flux. They are an attempt at preservation.

Harriet Said, her debut, is set outside the city on the coast. The narrator is an adolescent girl, somewhat in the power of another, Harriet, who supervises her dangerous liaison with a middle-aged married man known to them as the Tsar. The girls are precocious and beady: but they also miss the point of certain developments in the adult life which surrounds them, and with which, as with fire, they proceed to play. A diary is kept (this, after all, is the Forties—a great age for diaries). They peer at the people of the neighborhood, and peep through curtains as the Tsar and his wife make love. Together with a brash male friend, the Tsar admits the nymphets to his house when his wife is away. There is a bit of drinking, a bit of piano playing. There is confusion, grief, remorse, but nothing in the way of congress. This is the scene which upset the publisher. God alone knows what he would have made of Lolita: he would have been very sure that no printer would have dared to print that.

Eventually the narrator is “had” by the Tsar, and it is like a visit to the dentist, no worse. Harriet had seemed to impose a sadistic regime of humbling the Tsar, and humbling the Tsar had been misconstrued by her friend to mean doing rude things with him in the sandhills. But it also leads to a clobbering to death of the Tsar’s wife when she arrives home unexpectedly during a further tryst. In the sandhills the “seduced” girl reflects:

The truth was that I was fond of him. He was part of the small group of souls that I was responsible for, who depended on me not to hurt them: my mother, my father, Frances. It did not occur to me till later that the Tsar should feel responsible for me.

She does, in fact, hurt this man, and other people too. At the finish, there is isolation, and “responsibility” is mocked. For one thing, she has suffered the loss of Harriet, whose role in her life she has come to comprehend.

This is an absorbing novel, with its own voice. But it is a little incoherent, and it is not always clear—at the tactical level, so to speak—what is going on. Except in The Dressmaker, Beryl Bainbridge is sometimes neglectful of her responsibility toward the reader, who needs more nursing than he receives. This does not interfere, however, with her ability to work up climaxes and to secure the reader’s attention at the strategic level. It may be that a question arises concerning the violent deaths she is apt to inflict, as here. Is she really a writer of thrillers, of what Graham Greene regards as entertainments—fashionably black ones at that?

A Weekend with Claud was published in 1967. Her interest in isolation is expressed strategically—in the structure of the novel. Maggie and her friends go to stay in the country with the pretentious bearded antique dealer, Claud. A shot rings out, and a self-intoxicated elderly Jewish woman, Shebah, a virtuoso griever and outcast, is mildly winged. The same story is told and retold by members of this circle of friends—Maggie, Shebah, the self-assured Victorian Norman, as he’s nicknamed—and a sense of the separateness of each one of them is conveyed. Maggie may at one or two points be felt to incorporate a portrait of the artist, or of part of her: she is fascinating, adored, doubted, slatternly, a manipulator of people’s interest in her, a loser in love, a great actress—a poor punctuator, very likely. These friends need one another, in varying degrees: in varying degrees, too, they are alienated from one another, and disloyal, if not positively beady.

Advertisement

In this novel especially, the storytelling can be hard to follow, and the reader stumbles over a profusion of rare words that somehow seem doubtfully spelled. And yet none of this appears to matter very much, and the tactical successes are frequent and cherishable. In its best episodes, the book is wonderfully alert to the flow of feeling between the friends, to the accesses of hostility, to the bitter humor which envelops its losses and departures. On this showing, Beryl Bainbridge might be thought to belong to a particular line of English women writers: intelligent outcasts, some of them, specialists, some of them, in what makes families families. But there is probably no call to imagine this sort of sisterliness for her. At her most “feminine,” she can be very like the male writer of the Forties, Henry Green, that specialist in inconsequentialities and longueurs.

Another Part of the Wood, published a year later, is rather a similar book, though it has more of a story to tell. A second set of people from the English provinces, locked in a state of dependence and indifference, embark on an outing to the country. A boy called Balfour, with boils and a blemished complexion, and a bad case of shyness, is in the habit of helping a friend who has an estate in North Wales. This man, George, is preoccupied with the sufferings of the world, and, above all, with those of the Jews, and reckons that he can do something about them on his estate. Perhaps his glen may be brought to resemble, or does resemble, an Eden: “Evil lay beyond the glen.”

From beyond the glen comes this party of friends and semi-friends, intent on a submission to pastoral. Their leader is the pretentious bearded Joseph, who is divorced (as in some sense are so many Bainbridge persons), and who has with him a small son and a girl, Dotty. He is very opinionated, and a great narcissist and groomer of his appearance. And he is tired of Dotty, who takes on progressively, in the course of being shed, what seems like a kind of integrity.

Beryl Bainbridge sometimes makes play with photographs of her casts, and toward the close of this idyll a snapshot is taken of the imperfectly-associated, divorce-prone company:

It was important to Dotty that there should be some record she could keep of this last time spent with Joseph. In a drawer or the pocket of an unused handbag. Scent of powder clinging to the celluloid square. Joseph assembled them on the chairs, Lionel next to his sweetheart, Dotty to the right, clad in her flowered coat, Roland on her knee. Behind with folded arms, stern, Victorian, Balfour, Kidney, George.

It wasn’t right. After a little thought he asked George to lie down in the grass at their feet, full length, feet crossed at the ankles, his head propped upright on his hand.

The scene is touching, like a Victorian sporting group as commemorated on a Grecian urn—except that this is a team that could not learn to play together. It may be that there are no true teams at all, only photographs.

Toward the end a drama starts which provides the novel with an urgent momentum: the small boy dies of an accidental overdose of sleeping pills. This event, which is postponed and postponed, so that it is felt to be forever impending, may also be felt to be hideous: hideous because cunningly solicitous of the isolated reader’s need to be entertained (and this is certainly a place where she does show solicitude for the reader), and because it may be suspected to belong to some shadowy sermon on Joseph’s emancipated disregard of his responsibilities. The suspicion may impair our appreciation of the efforts made by the insipid, intrepid Dotty to escape from her contemptuous love of Joseph. The boy’s death (while his father plays at being a businessman over a Monopoly board) will be harder to bear if we are persuaded that it is meant to teach this lesson, and also to entertain.

Strange to relate, the doctrine about loneliness which is attributed to her father in Beryl Bainbridge’s article about Liverpool is attributed in the novel, more or less verbatim, to the delinquent Joseph. It may be that there is an Oedipal strain in her fiction: in Harriet Said a girl is fond of a father substitute and is plunged into matricide, while here a delinquent father is slain with intimations of child murder. At any rate, it is striking that Beryl Bainbridge’s real father and the bad father of this novel are both credited with this simplistic doctrine about loneliness, to which her stories contribute a train of supporting evidence: they are adamant that intimacy and teaming-up conceal hostility, desperation, and an outcast condition. And yet they also contribute a good deal in the way of qualifying evidence, in the way of relief. There are occasions when people help each other, when need answers need. Balfour “was careful not to throw George off balance by appearing to listen to him”—so he stares at the floor. Balfour’s shyness is abysmal, destructive of his chances: yet he realizes here that the other man’s shyness must be tended and taken into account.

It is as if an old anxiety about the reality or sufficiency of her father’s love has led her to make use of his bleak doctrine about human relationships in order to characterize a “bigoted” fictional father. An element of blame seems to attach to the doctrine—and perhaps to fathers too—and, as I say, the doctrine is effectively denied in her fiction at large, bleak as this can be at times. Bleak as it can be at times, her fiction has in it ties of affection. It has saving instances, merciful exceptions, thoughtfully averted glances. In the course of the party’s Chekhovian dawdling in the glen, the small boy is tenderly evoked, and so is Dotty, and so is her drawing together with the hangdog Balfour.

The Dressmaker, which was published last year in London, is a magnificent book. It is like her first novel, Harriet Said, in being tightly told and commercially promising, with a twist in the tail. It has an “arsenic and old lace” crime aspect, but it is not seriously damaged, any more than the other novel is, by moving, to the extent it does, in the direction of the sophisticated crime story. The two middle novels hang together just as closely: both capture the listlessness of a set of the more or less ill-assorted, and both plainly reflect an experience of the friendships afforded her by her own generation.

The first and last novels take her back to her childhood during the Second World War, and The Dressmaker represents an observation of the working-class life of her parents’ generation. Her imagination, which can give the impression of roving back to Victorian times, is often prepared to settle for the Forties, which, as described by her, can seem quite Victorian. The idea of isolation emerges again here, and is invested with a special irony. Kinship is seen as shelter: but this is a security which obeys internal laws so fierce that loneliness may appear preferable, and it can land the individual in a predicament more painful than any to which a “free” girl like Dotty risks exposure. We have already been taught that kinship cannot prevent isolation: now we are shown that it can cause it.

The Dressmaker concerns two aunts, Nellie and Marge, and their niece Rita, who lives with them in their house in Liverpool. The war is on, and the American army is encamped nearby: overwhelmingly exotic and wealthy and sexy. To fraternize with the Yanks is held to be like fraternizing with the enemy, but the more adventurous women are willing to risk the local equivalent of a shaven head. The local life, to the GIs, is as alien as Saigon was to their successors. Rita, who is no bar-girl, takes up with one of them, Ira, a neat, nasty, savorless farm boy.

The two old girls are starkly contrasted. Auntie Nellie, the dressmaker, is a martyr and a leader—who is herself dragooned by a devotion to her mother’s standards: “She was only marking time for the singing to come in the next world and her reunion with Mother. It was different for Marge, a foolish girl of fifty years of age….” Marge is eccentric, flighty, and relatively free. Her husband was killed in the Great War, and her one chance of a remarriage was crushed by the invocation of Nellie’s iron laws of propriety. Marge is forced to share in the family martyrdom, but she remains potentially rebellious. The type of relationship that exists between these two women, a partnership of the stern and the flighty, has long been at the center of working-class life in Britain, and Beryl Bainbridge has done well to acknowledge the importance of spinsterliness and sisterliness in this setting. Very few writers have been aware of it.

Nellie, her tape measure round her neck, is the boss. She is the mistress of lovely widths of serge and shades of beige. Dressmaking is her skill, her mystery and her subsistence. Here she is studied at her sewing machine by Rita’s widower dad, a butcher and black marketeer, who lives apart from the family:

As long as he could remember, Nellie had played the machine, for that’s how he thought of it. Like the great organ at the Palladium cinema before the war, rising up out of the floor and the organist with his head bowed, riddled with coloured lights, swaying on his seat in time to the opening number. Nellie sat down with just such a flourish, almost as if she expected a storm of applause to break out behind her back. And it was her instrument, the black Singer with the handpainted yellow flowers. She had been apprenticed when she was twelve to a woman who lived next door to Emmanuel Church School: hand sewing, basting, cutting cloth, learning her trade. When she was thirteen Uncle Wilf gave her a silver thimble. She wasn’t like some, plying her needle for the sake of the money, though that was important: it was the security the dressmaking gave her—a feeling that she knew something, that she was skilled, handling her materials with knowledge; she wasn’t a flibbitygibbet like some she could mention.

Marge is, by comparison, a flibbitygibbet. Most of her merits, though not the supreme merit of her membership of the family, go unconceded by her sister.

The aunts are very poor. One guide to their station is supplied by Marge’s reaction to the delights with which Valerie Mander has become acquainted through her association with a GI. Marge is in conversation with Valerie’s mother, who

couldn’t wait to tell her all about him. Valerie had met him at a dance a week ago and he’d taken her out nearly every night since, to the State Restaurant, the Bear’s Paw, to the repertory company, to some hotel over on the Wirral, very posh by all account.

“The repertory company?” said Marge, bewildered.

“To a play,” said Mrs. Mander, “with actors.”

“He must have money to burn.”

As someone able to sustain a flirtation with amateur dramatics, Marge ought not to have been bewildered, but the point is made. This exchange indicates—it’s the kind of thing one may forget to say on occasions like this—that Beryl Bainbridge is a very witty writer. The wit is never sported or exhibited. It is shy. But it is rarely absent.

It is not grandiose to suggest that a key feature of the aunts’ world is its Racinian observance of a decorum of manners in the context of a conviction of the nearness of depravity and ruin. Their world is not grounded primarily in church religion, though there is a religious aftermath to be considered, but in a religion of the family, in a form of ancestor worship which regulates and forbids, and in the cult of respectability practiced by the dangerously poor. During the war there was a well-known official slogan, “Careless talk costs lives,” and this is a slogan which Liverpool respectability had lived up to anyway, come war or peace, since its earliest days.

A rigid propriety of word and deed is continuous in the lives of this family, and it unfits Rita for her dealings with the improper Ira. Among her first impulses after she has fallen helplessly in love with him—and it is instantly regretted—is to correct his blasphemies, his careless talk. In doing so, she ruins her chances straight away. Clandestinely he turns toward Marge Wildfire, whom he understands. The mating of these two—Vénus toute entière—is outlandishly depraved by local standards. Only catastrophe can ensue, and what does ensue is like the outcome of some kind of classical tragedy: the deadlock which results from a confrontation of inimical codes and imperatives has to be resolved in blood.

Nellie’s world, in which careless talk costs lives, in which umbrage is endlessly taken, in which most forms of spontaneity and pleasure are inexcusable and apt to involve a burning of money, is reproduced to perfection in this novel. Part of its distinction is to reveal Nellie as a heroic and sympathetic presence, while also insisting that her code is one according to which almost everything is vile that does not serve the family’s sense of mission, and its survival as an economic and eschatological unit: they are all bound for heaven—except, perhaps, for some flibbitygibbets one could mention. Poverty is conceived of as enjoining something like a military or monastic discipline. It produces an asceticism of survival based on rejection and reproach.

This way of life was set up in the nineteenth century—against the background of religious certainties which presently began to fade—in order to cope with the difficulties of making out, on the verge of ruin and disgrace, in overpopulated, hard-working industrial cities. It has persisted into the present: there has been no fading of certain of the essential conditioning factors. Nellies are still sewing, and Marges are still struggling to escape. After the Second World War, at a time when it was felt that this type of working-class asceticism was passing into history, there was a literary cult of it. Nellie’s iron laws became romantic, and so did the varieties of release that young males pursue in such a setting. But Beryl Bainbridge’s novel should not be regarded as a belated response to this cult, which has now ceased. She does not romanticize her Forties, for all the delicious references to Wolseley cars and Gold Flake. She is clearer than the cult ever was that Nellie’s merits, which have to do with honesty and strength of mind, exact a high price. She is clear that they cost lives.

To revert to the sort of question I have asked before, does she make an entertainment, a performance, out of this true stuff, doing it harm? The ending of the novel has a touch of grand guignol. And when Nellie, the justified sinner, is about to sew a chenille shroud for Ira and to dispose of his body, she cries: “We haven’t had much of a life. We haven’t done much in the way of proving we’re alive. I don’t see why we should pay for him.” This is out of character for Nellie: it is the author speaking. Equally, the prominence in the catastrophe of Nellie’s house-proud zeal is a little too entertainingly implausible. But none of this is of more than incidental significance. Nellie and Marge and their kin haven’t had much of a life, but the life with which the novel supplies them is formidable. It is deathly and deadly. It is a life which is capable of jabbing with its scissors at the heartland of America. But it is capable of other things besides. It has its own humor, and its own honor. And the spectacle of it can be enjoyed even by those who are far from wishing to romanticize the Liverpool they inhabit.

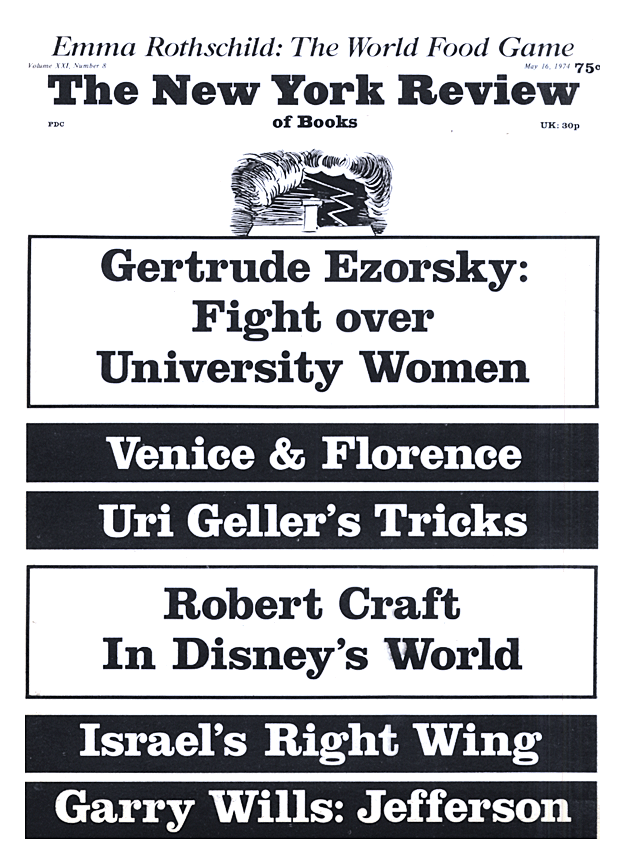

This Issue

May 16, 1974