Penelope Mortimer’s new novel is so witty you think it’s a comedy, and so troubling you think it’s a confession. I suppose the best description is an allegorical romance drawn from elements of the author’s life. But the meaning—translucent at best—is never narrow, for it touches the ocean floor of sexuality. Whoever remembers The Pumpkin Eater remembers Mrs. Mortimer’s detached scenes of absurd but revealing dialogue, with ominous hints dropped among the bright inanities. He also remembers the luminous, tragic ending, with the mother, in flight from her own guilelessness, captured inside a tower retreat by her ignorant children and calculating husband—a mother triply betrayed, and drained of forgiveness.

In Long Distance the heroine (and narrator) has the simplicity and vitality of her predecessor. But she learns to preserve the blessing of a candid, ardent, harmless nature by at last shielding it behind an appearance of “normal” conduct. The fable of her progress is intricate and bewildering, much too unusual to be taken for granted. To so enigmatic a story the most useful approach is an interpretative summary, even if parts of my account will have to be guesswork.

The heroine seems to be named Dora. She has apparently fled from her husband because he deceived her too cruelly; maybe another woman has had a child by him. Certainly, Dora has had a number of children; and she yearns miserably for this impossible partner, irresponsible father and fickle lover, in whom she sought “the body of a boy, the wisdom of a father, the sensibility of a woman and the strength of Almighty God.” Here is the dangerous addiction from which she must liberate herself. When she grows tired of flight, she comes to live in a mysterious mansion where time is abolished and the present blurs with the past. The residents must submit themselves afresh to the formative experiences that they have repressed from their memories. In funny and puzzling ways, therefore, they treat one another as surrogates for parents, lovers, children. Most readers will feel uneasy about the mixture of farce and pathos that flows through the fantasy of life in this setting. If my analysis sounds bathetic or dreary, it is because I cannot include the passages of brilliant parody, self-ridicule, and word-play that interrupt and enrich the riddles of the action.

One of the men, named Gondzik, becomes Dora’s confidant and adviser, her attachment to him seems analogous to transference in psychoanalysis. As the story proceeds, one recognizes bizarre parallels to the Watergate scandals. The management of the institution, located in a separate office. building, is remote and imperious. Yet rumors keep suggesting that the staff is shaky and corrupt. Gondzik, who acts so sympathetic, turns out to be an agent of the management, spying on and manipulating the other residents in the name of security.

Existence at the mansion is punctuated by phantasmagoric re-creations of old and archetypal events, lived in reverse order of time. So the heroine watches a grotesque play that mixes ingredients from Oedipus Rex, Peter Pan, the Gospel according to St. John, and other sources. In this burlesque of a Christmas pantomime, one character is an irresponsible father who won’t grow up; another is a mother who can’t let go of her mature children. It is a hilarious but nightmare version of Dora’s recent life. She cannot endure it and breaks down. Therefore, she must be removed to an earlier stage and live through a paradigm of motherhood. This lunatic ordeal is arranged in a house outside the grounds of the mansion. Here Dora works frantically, looking after a horde of nameless children and a chaotic dwelling. But even while she loathes the tedium and exhaustion, her need for roots is too strong; she fixes herself madly in the maternal occupation. Eventually, of course, the children move off and her labor loses its rationale. But she clings to the place, waiting for the “baby” to come home. Finally, she is returned willy-nilly to the mansion.

Dora has not yet learned to guard against simple tenderness. After a brief and frustrating sexual affair that reveals her vulnerability, she decides to escape by making her way to the hut of a fatherly gardener who had once encouraged her to be a free, creative spirit. I suppose filial love should be an easier state than mature passion. It does not yet occur to Dora to try existence without men. A newly acquired dog, as affectionate and simple as herself, goes with her, and she does join up with the gardener. But he is horrified. Although the hut means home to her, he carries the girl back to the mansion and kills the dog.

Now Dora is sent to the “West Wing,” a hospital where extravagant people are made average. Shock treatments and drugs are employed to train her not to hurt herself with strong emotions and hasty submissions to friendly males. Almost destroyed by the treatments, she suddenly realizes that if she can pretend to be a “normal” (i.e., average) person, she will be declared cured. So she begins to veil her emotions, making believe that nobody matters deeply to her. As a reward for such evidently good behavior, she is allowed to enjoy an affair with a boy who would have been appropriate to her in early adolescence. For a while, she gets it right; and instead of letting on what she feels like doing, she drifts coolly into a physical relationship that involves much sensual delight but no responsibility. Caught up in the affair, she blunders and shows a radical fondness for the boy. But she manages to cover up the failure, passes a calisthenic endurance test that might be administered to a child, and secures her bill of health.

Advertisement

A still earlier sexual stage seems to follow. The boy-man returns in an onslaught that suggests the painful rape of a virgin, and this deed is repeated. At first, she hides the pain, quite successfully, but soon she feels confident enough to discuss it with him; and so, in a weirdly logical sequitur, they retreat to extra-vaginal sexuality. Dora survives and even wishes to stay in the West Wing. But it has served its purpose; the doctors believe she has conquered her predispositions; she is ready for the mansion again.

The rest of the book is the most ingenious and entertaining portion. Although the action continues dreamlike and regressive, a development that had seemed tangential now dominates the plot. The inner self of the heroine shrinks from the mask she has so laboriously created, while the mask assumes depth and independence. The heroine’s self begins to divide up. The nobler part requires loyalty, affection, contemplation, and rootedness. The persona wants flux, action, deceit, success—she is determined to beat the men at their own game. It looks as though the novelist rejects our common ideal of an integration of personality and proposes instead the ideal of fission. By relinquishing the persona that nourishes itself on deceit, the heroine will be cured of the insatiable pining for a boy-father-woman-god. This is hardly the doctrine preached by Gondzik.

The contemplative inner self watches the vicious persona act in ways that disgust her. She sees it master situations that the less adaptable self would avoid. There is a splendid comedy of pronouns as “I” and “she” fall out. Meanwhile, a final lover courts the heroine. His name is Adam. He belongs to a gang of pleasure-loving, cruel decadents who have taken over the mansion, its grounds, and its pond. Their sophistication and polymorphous perversities startle the inner self. But the persona easily betters their instruction as they try, I think, to undermine all the instincts that support mature sexuality, tenderness, and family ties. At this stage of the fable there seems to be not a sympathy but an opposition between eros and procreation. The whole distinction between male and female roles begins to dissolve. All through the novel, the heroine’s imagination has kept reviving her girlhood, tomboy pleasure in the story of Hiawatha. The persona enters gladly into these fantasies, capers with the sybarites, and only pauses when they discover—and joyfully carry off—a tiny female infant drowned in the pond. This, we later learn, is the unwanted child born to another woman of the mansion, fathered by the very boy who had joined Dora in the West Wing.

Now the sybarites have gone too far. Weakening the old relation between the sexes is one thing; destroying parenthood is another. I suppose the mansion would collapse if the sybarites had their way. So they are brought to order and reduced to conventional conduct. The administration assumes that the heroine was acting as an agent provocateur in order to expose these delinquents. She is congratulated and invited to the office, where she will meet Mr. Hathaway, who manages matters for the Director.

The series of episodes that follows occupies the last quarter of the book and makes a symmetrical pattern of comic surprise and fulfillment. When Dora meets Hathaway—an executive type with much in the way of manners and nothing in the way of scruples—he asks her to work for him. The job will be to transcribe tape recordings that Hathaway may present to the governing board as evidence incriminating the opponents of his regime. The division between Dora’s inner self and corrupt persona has got so far that even while she is horrified by the proposal she hears the persona accept and bargain for a tremendous salary that will be spent on fashionable clothes and jewelry. Settling down like a presidential secretary, the persona soon manufactures transcripts in which Gondzik is made to utter seditious speeches that were really delivered by herself. Mrs. Mortimer’s genius for mimicry takes over; and the dialogues, like so many other speeches in the novel, become satiric pastiches of what passes in our world for intelligent remarks. Gondzik is confronted with the forged documents before an investigative committee, found guilty in spite of his protests, and sent to the West Wing. The persona is now too ambitious to tolerate the inner self or to stay with Hathaway. She packs up to leave and drags her partner to a last function in the office.

Advertisement

Here Mrs. Mortimer gives the action a turn that must be called beautiful. She could simply ship the corrupt persona off into the great outside, there to become a brazen career woman of the most sinister class; and she could leave the purified self in a stasis of virtue. Instead of this, she has the purified self suddenly find its own voice, in a bathetic yet passionate demand to know where her dog was buried. I suppose this minute tribute to selfless affection is enough to stun a society built on the postulate that such an impulse cannot exist. Intimidated, the staff surrender the information. Dora leaves them (and the persona) paralyzed, in poses that suggest death.

The heroine has taken the devotion she was not allowed to offer a man, and bestowed it on the animal emblem of that virtue. Purged, she can at last see the once-beloved spouse whom she has missed so long. He sits on the stone bench where, I suppose, they first met, long ago. His deceit no longer clouds her vision. Staring at him, she backs away until he disappears. She is withdrawing, it seems, into the past before they met; and since she has now lost the false persona, she will never start the affair that led to her agony.

With the heroine transformed, the allegory she created is also transformed. The mansion comes under new management, headed by a blind seer but responsive to Dora’s desires. She will remain there, thriving on the old values, rejecting the world of male cynics like Hathaway and forming a community with people like herself. Gondzik is recalled from the West Wing, marries the mother of the drowned child, and takes up the post of gardener. Instead of posing as philosopher and guide, he can follow the example of Candide.

Throughout the novel a vessel of goodness and truth keeps manifesting itself in the shape of a motherly Old Woman. She lives in the woods and tells the heroine the story of Dora’s life. She never lies; she serves as a midwife, willingly accepts death, and worries about trees, flowers, vegetables. This is the order of nature, our ultimate consolation. It is the Old Woman’s example that strengthens the heroine; and at the end of the novel it looks as if Dora is going to inherit her role.

For all its originality, the novel is filled with echoes: Kingsley’s Water Babies, Butler’s Erewhon, Orwell’s 1984, Nixon’s tapes. The heroine quotes old songs and nursery rhymes in absurd illustrations of her teachings. She resurrects the clichés of wisdom literature, giving them life through clownishness. Much of the charm of the novel depends on Mrs. Mortimer’s knack of playing with the obvious and familiar until it seems subtle. At moments the whole story becomes a send-up of our new genre of parable-romances: Golding, Murdoch, and company.

But the strongest pleasure we are offered, apart from the novelty of the doctrine, is the brilliance of the style. Among the many cunning features are the tricks with names. Is Gondzik a medley of “God,” “kind” (for child), “dog,” and “king”? Is “Dora” derived from the childlike bride of David Copperfield? Is “Hathaway” a corruption of “Hiawatha”? Mrs. Mortimer seldom writes a sentence that would not be shapely if spoken. Her language keeps its freshness without dropping into preciosity. Her ironies are gentle and humorous. Even the types she condemns are seen through the eyes of Molière or Horace, and not those of Juvenal. The most constant butt of the satire is Dora herself, who is surely a version or caricature of the author.

One asks whether this fortunately brief novel is a success. I think not. The design could hardly be more thoughtful or elaborate. We are prepared carefully for every effect; the meaning is tactfully expounded; themes and images are distributed in graceful repetition, like motifs in a symphony; the heart of the matter stays poetically dark and alluring. But far too much is going on. The comedy quarrels with the allegory. The obscurity is too heavy for the entertainment. The book is worth reading twice.

As a token of Mrs. Mortimer’s accomplishment, we may set Guy Davenport’s Tatlin! beside it. Here are five stories and a short novel. Davenport uses several of Mrs. Mortimer’s devices, and he too echoes Erewhon. He strives for an elegant style, maintains a cool, ironic tone, and enriches his work with many allusions. In the short novel, The Dawn in Erewhon, he seems to recommend a way of life that would combine amoral, bisexual orgies with physical fitness programs, aesthetic sensibility, and the most strenuous intellectuality. I am afraid he will hold few readers. His common way of interesting us is to produce startling combinations of historical and fictitious personages in curious places, and to fill them with exotic thoughts and miscellaneous learning. The style is sadly remote from speech and abounds in precious phrases. Tedium is the product of too much cleverness. I think of Firbank, whose whimsy was so much less direct and more evocative. A good many of Davenport’s scenes will please voyeurist highbrows; and people who desire an easy method of learning the anatomy of the genitalia may find these stories valuable.

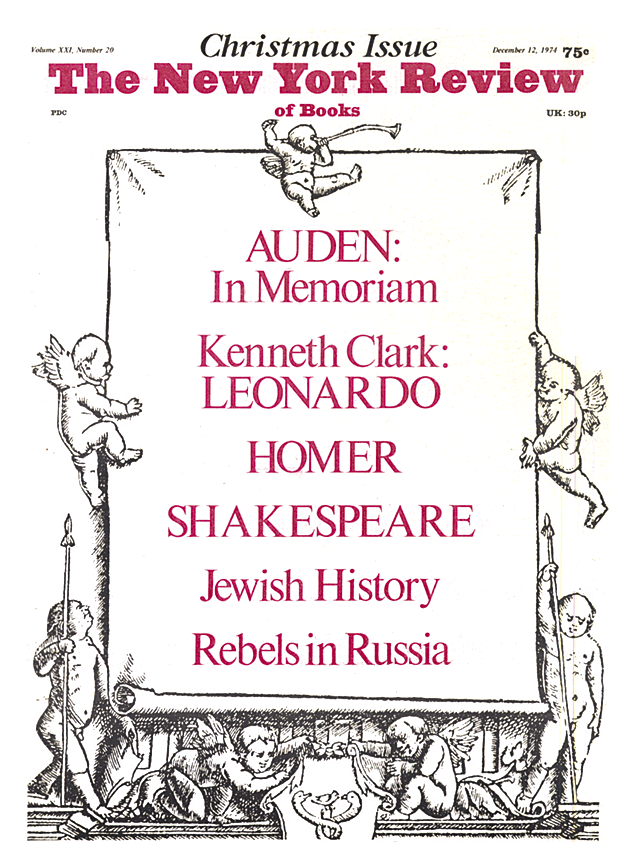

This Issue

December 12, 1974