In response to:

Surviving Death from the October 31, 1974 issue

To the Editors:

Mr. J. M. Cameron, in his admirable essay on death, in your issue of October 31st, repeats a statement made far too often over the past century, to wit: “Alone of the animals man knows he will die.” Now, there is no possible way that this statement can be ascertained to be true, so why make it? The fact is that, quite to the contrary, there are several ways in which the statement can be shown to be almost certainly untrue. Innumerable cases—and not merely of faithful Rover pining away on his master’s grave—have been recorded of animals who have seemingly willed themselves to die. How could they choose the means of achieving this end if they were unable to conceptualize both the means and the end? What of the animals that, in old age, appear to separate themselves from the rest of the herd/tribe/pack in anticipation of death? And surely the animal that, on having its leg caught in a trap, gnaws the leg off in order to escape may be thought to have an acute sense of its alternative fates; if so, the alternatives may well be presumed to include death. Moreover, animals fighting with other animals and finding their lives in jeopardy adopt postures that simulate woundedness and death. (In the case of the possum, its posture of pretended death, whatever may be thought of it scientifically, has at any rate become a part of our language.)

Our arrogance in assuming that we are alone among animals in knowing we will die is analogous to the arrogance we used to assume in respect to speech. For centuries, we were certain that, because we had speech, we were alone among animals in having language. Belatedly, we have learned that animals have many and highly varied forms of language, and the evidence is beginning to accumulate that these forms are no less vivid and complex than ours. Chimpanzees who have been taught sign language are quick to invent metaphors in that language. Upon learning the meaning of “dirty” as “soiled,” for example, they soon apply it as a term of insult in the course of quarrels with fellow chimpanzees or human companions; they say, in effect, “What a dirty trick!” in very nearly the same fashion that we do. An animal that communicates by means of metaphors may be every bit as death-haunted as we are, and for the identical reason: the prospect is intolerable.

As for me, having scrutinized the horror of death for sixty years, I have decided never to die. My decision gives meager pleasure to my children and grandchildren, but one cannot hope to satisfy everybody.

Brendan Gill

New York City

J. M Cameron replies:

How we are to take the applications of such concepts as “understanding,” “expecting,” and so on, to the behavior of the other animals is a hard question, as is the sense, if any, in which they may be said to use language. None of the facts cited by Mr. Brendan Gill strikes me as helping in any way to answer these questions. To suppose that dogs or chimpanzees in full health and vigor know they will die seems just preposterous. It wouldn’t be improper to say of a very sick animal that it knows it is dying: the evidence for this is its behavior. But this is the sense in which Rover’s behavior at the hour when his master usually comes home leads us to say that Rover “expects” his master. But we couldn’t say that Rover expects his master to come home next week, for this would be to imply that Rover has a lot of concepts he plainly lacks. Equally, Rover couldn’t be said to pretend that he expects his master. We can say that Rover is obedient just as we say this of a soldier or a child; but this application seems to lie midway between the application to the human case and our saying that planets and projectiles obey the Newtonian laws. So they do; but they are not on that account intelligent or praiseworthy.

The question about whether or not animals have language is a different question from the question whether or not animals communicate with each other. Of course, they do. As to whether what they say counts as language in the sense in which language has been a matter of interest and inquiry for grammarians and philosophers, this is something else. To maintain that they have language in this sense seems to me not so much false as unintelligible. I can imagine the conversation of the brutes, as in Aesop or Beatrix Potter. This is to implant homunculi deep inside them.

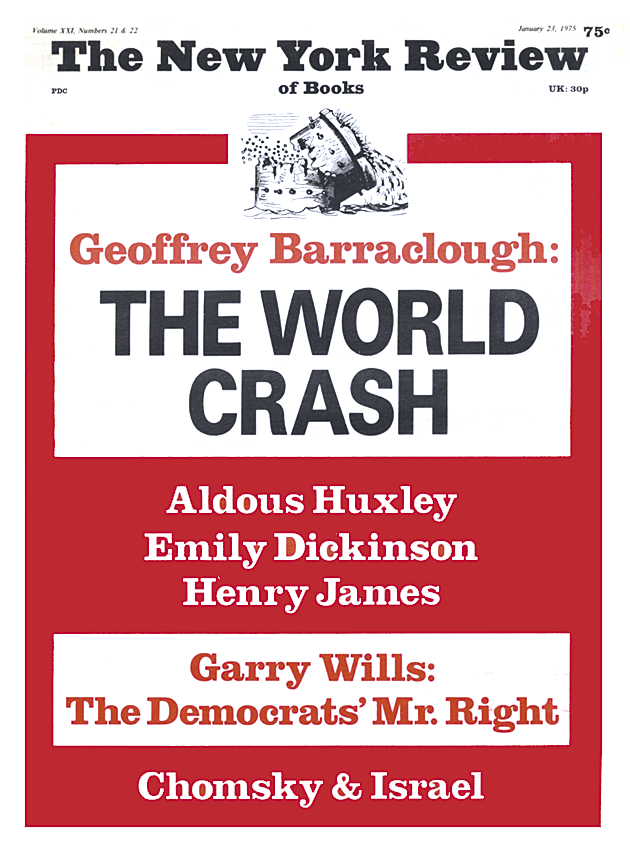

This Issue

January 23, 1975