A black child of eight, a girl who lives in southern Alabama, just above Mobile, told me in 1968 that she knew one thing for sure about who was going to be president: he’d be a white man; and as for his policies, “no matter what he said to be polite, he’d never really stand up for us.” Already she knew herself to be a member of “us,” as against “them.”

A few miles away, a white child of nine, a boy, the son of a lawyer and plantation owner, had a rather different perspective on the presidency: “The man who’s elected will be a good man; even if he’s not too good before he goes to Washington, he’ll probably turn out good. This is the best nation there is, so the leader has to be the best, too.”

A child with keen ears who picks up exactly his father’s mixture of patriotism and not easily acknowledged skepticism? Yes, but also a child who himself—by the tone of his voice and his earnestness—has come to believe in his nation’s destiny, and in the office of the presidency. How about the governor? “He’s better known than most governors,” the boy boasts. Then he offers his source: “My daddy says that we have a better governor than they do in Louisiana or in Georgia. (He has cousins in both states.) And he says that our governor makes everyone stop and listen to him, so he’s real good. He knows how to win; he won’t let us be beaten by the Yankees.”

Is this more sectional bombast, absorbed rather too well by a boy who now, a teenager, hasn’t had the slightest inclination to develop the “cynicism” a number of students of the process of “political socialization” have repeatedly mentioned as prevalent? Or is it, more likely, the response of a child who knows what his parents really consider important, really believe in—and fear? “I took my boy over to my daddy’s house,” the child’s father recalls, “and we watched Governor Wallace standing up to those people in Washington; he told the President of the United States that he was wrong.”

The boy was then four, and no doubt even were he to see a child psychoanalyst for several years he would not at nine, never mind at fifteen, recall the specific event his father and grandfather have very clearly in mind. But time and again he has heard members of his family stress how precarious they feel in relation to Yankee (federal) power, and therefore how loyal to a governor who gives the illusion of a successful defense of cherished social and political prerogatives.

Up North, in a suburb outside Boston, it is quite another story. At nine a girl speaks of America and its leaders like this: “I haven’t been to Europe yet, but my parents came back last year and they were happy to be home.” Then, after indicating how happy she was to have them home, she comments on the rest of the world, as opposed to her country:

“It’s better to be born here. Maybe you can live good in other places, but this is the best country. We have a good government. Everyone is good in it—if he’s the president, he’s ahead of everyone else, and if he’s a governor, that means he’s also one of the people who decide what the country is going to do. There might be a war, and somebody has to send the troops by planes across the ocean. If there is a lot of trouble someplace, then the government takes care of it. I’m going to Washington next year to see all the buildings. My brother went two years ago. He really liked the trip. He came back and said he wouldn’t mind being in the government; it would be cool to go on that underground railroad the senators have. He said he visited someone’s office, and he was given a pencil and a postcard, and he wrote a letter to say thank you, and he got a letter back. His whole class went, and they were taken all over. They went to see some battlefields, too.”

She doesn’t know which battlefields, however; nor does she know which war was fought on those fields. She is one of those whom southern children of her age have already learned to identify as “Yankees,” even know to fear or envy. There are no equivalents for her, however—no name she is wont to hurl at southerners or, for that matter, anyone else. True, she learned long ago, at about four or five, that black children, whom she sees on television but has never gone to school with, are “funny,” and the single Japanese child she had as a classmate in kindergarten was “strange, because of her eyes”; but such children never come up in her remarks, and when they are brought up in the course of conversation with a visitor, she is quick to change the subject or go firmly silent. Nor is there any great amount of prejudice in her, at least of a kind which she has directly on her mind. Her drawings reveal her to be concerned with flowers, which she likes to help her mother arrange, with horses, which she loves to ride, and with stars, which she is proud to know rather a lot about.

Advertisement

The last interest prompts from her a bit of apologetic explanation: “My brother started being interested in the stars; my daddy gave him a telescope and a book. Then he lost interest. Then I started using the telescope, and my daddy said I shouldn’t, because maybe my brother would mind, but he doesn’t.” And, in fact, her parents do have rather firm ideas about what boys ought to be interested in, what girls ought to find appealing. Men run for political office, she knows. Sometimes women do, but only rarely; anyway, she won’t be one of them. In 1971 she thought the President was “a very good man; he has to be—otherwise he wouldn’t be president.” The same held for the governor and the town officials who make sure that all goes well in her neighborhood.

When the Watergate scandal began to capture more and more of her parents’ attention, she listened and wondered and tried to accommodate her longstanding faith with her new knowledge: “The President made a mistake. It’s too bad. You shouldn’t do wrong; if you’re president, it’s bad for everyone when you go against the law. But the country is good. The President must feel real bad, for the mistake he made.” After which she talked about her mistakes: she broke a valuable piece of china; she isn’t doing as well in school as either her parents or her teachers feel she ought to be doing; and not least, she forgets to make her bed a lot of the time, and her mother or the maid has to remind her of that responsibility.

Then she briefly returned to President Nixon, this time with a comment not unlike those “intuitive” ones made by Australian children (from New South Wales) in Professor Robert Connell’s book The Child’s Construction of Politics. “A friend of mine said she didn’t believe a word the President says, because he himself doesn’t believe what he says, so why should we.” What did the girl herself believe? “Well, I believe my parents, but I believe my friend, too. Do you think the President’s wife believes him? If he doesn’t believe himself, what about her?” So much for the ambiguities of childhood, not to mention such legal and psychiatric matters as guilt, knowing deception, the nature of self-serving illusions, and political guile.

As one listens to her and others like her—advantaged children, they might be called—one wonders, again, where are to be found the symbols of political power, of pomp and circumstance, that are meant to impress, inspire, and intimidate—the “gladiators” of Simone Weil’s essay I mentioned in my first article. Of course, there is nothing very dramatic to catch hold of; unlike black children, or Appalachian children, or even the children of well-to-do southern white families, the girl I have just quoted has no vivid politically tinged memories of her own, nor any conveyed by her parents to take possession of psychologically—no governor’s defiance, no sit-ins or demonstrations, no sheriff’s car and a sheriff’s voice, no mass funeral after a mine disaster, no experience with a welfare worker, no strike with the police there to “mediate,” no sudden lay-off (not yet, at least), followed by accusations and recriminations—and drastically curbed spending.

Such unforgettable events in the lives of children very definitely help to shape their attitudes toward their nation and its political authority. The black children I have come to know in different parts of this country, even those from relatively well-off homes, say critical things about America and its leaders at an earlier age than white children do—and connect their general observations to specific experiences, vivid moments, really, in their lives. A black child of eight, in rural Mississippi or in a northern ghetto, an Indian or Chicano or Appalachian child, can sound like a disillusioned old radical: down with the system, because it’s a thoroughly unjust one, for all that one hears in school—including, especially, those words quoted from the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution: that “all men are created equal,” that they are “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.”

Advertisement

The pledge of allegiance to the flag can be an occasion for boredom, at the very least, among some elementary school children; the phrase “with liberty and justice for all” simply rings hollow, or is perceived as an ironic boast meant to be uttered by others elsewhere. Here is what a white school-teacher in Barbour County, Alabama, has observed over the years:

“I’m no great fan of the colored: I don’t have anything against them, either. I do my work, teaching the colored, and I like the children I teach, because they don’t put on airs with you, the way some of our own children do—if their daddy is big and important. The uppity niggers—well, they leave this state. We won’t put up with them. The good colored people, they’re fine. I grew up with them. I know their children, and I try to teach them as best I can. I understand how they feel; I believe I do. I have a very bright boy, James; he told me that he didn’t want to draw a picture of the American flag. I asked him why not. He said that he just wasn’t interested. It’s hard for them—they don’t feel completely part of this country.

“I had a girl once, she was quite fresh; she told me that she didn’t believe a word of that salute to the flag, and she didn’t believe a word of what I read to them about our history. I sent her to the principal. I was ready to have her expelled, for good. The principal said she was going to be a civil rights type one day, but by then I’d simmered down. ‘To tell the truth,’ I said, ‘I don’t believe most of the colored children think any different than her.’ The principal gave me a look and said, ‘Yes, I can see what you mean.’ A lot of times I skip the salute to the flag; the children start laughing, and they forget the words, and they become restless. It’s not a good way to start the day. I’d have to threaten them, if I wanted them to behave while saluting. So, we go right into our arithmetic lessons.”

In contrast, among middle-class white children of our northern suburbs, who have no Confederate flag with which to divide their loyalties, the morning salute can be occasion for real emotional expression: This I believe! It is all too easy for some of us to be amused at or, more strongly, to scorn such a development in the lives of children: the roots of smug nationalism, if not outright chauvinism. But for thousands of such children, as for their parents, the flag has a great deal of meaning, and the political authority of the federal, state, and local governments is not to be impugned in any way. Among many working-class families policemen, firemen, clerks in the post office or city hall are likely to be friends, relatives, neighbors. Among upper-middle-class families, one can observe a strong sense of loyalty to a system which clearly, to them, has been friendly indeed. And the children learn to express what their parents feel and often enough say, loud and clear.

“My uncle is a sergeant in the army,” the nine-year-old son of a Boston factory worker told me. He went on to remind me that another uncle belongs to the Boston police department. The child has watched parades, been taken to an army base, visited an old warship, climbed the steps of a historic shrine. He has seen the flag in school and in church. He has heard his country prayed for, extolled, defended against all sorts of critics. He said when he was eight, and in the third grade, that he would one day be a policeman. Other friends of his, without relatives on the force, echo the ambition. Last summer, when he was nearer to ten, he spoke of motorcycles and baseball and hockey; and when he went to the games he sang the national anthem in a strong and sure voice. Our government? It is “the best you can have.” Our president? He’s “good.”

I pushed a little: was President Nixon in any trouble? Yes, he was, and he might have made some mistakes. Beyond that the child would not easily go. His parents had for the first time voted Republican in 1972, and were disappointed with, disgusted by, the President’s behavior over Watergate. But they have been reluctant to be too critical of the President in front of their children: “I don’t want to make the kids feel that there’s anything wrong with the country,” the father says. There’s plenty wrong with the President, he admits, and with the way the country is being run—and, he adds, with big business, so greedy all the time, as well as with the universities and those who go to them or teach at them; but America, he believes, is the greatest nation that ever has been—something, one has to remember, every president’s speech-writers, Democratic or Republican, liberal or conservative, manage to work into just about every televised address.1

Only indirectly, through drawings or the use of comic exaggeration or metaphorical flights of fancy, does the boy dare show what he has been making of Watergate, news of which has, of course, come to him primarily through television. Asked to draw a picture of President Nixon, the boy laughs, says he doesn’t know how to do so (he had had no such trouble a year earlier), and finally manages to sketch an exceedingly small man, literally half the size of a former portrait by the same artist. Then, as he prepares to hand over the completed project, he has some second thoughts. He adds a blue sky. Then he blackens the sky. He puts earth under the man, but not, as is his usual custom, grass. Then he proceeds to make two big round black circles, with what seem to be pieces of string attached to them. What are they? He is not sure: “Well, either they could be bombs, and someone could light the fuse, and they could explode and he’d get hurt, and people would be sad; or they could be balls and chains—you know, if you’re going to jail.”

Way across the tracks, out in part of “rich suburbia,” as I hear factory workers sometimes refer to certain towns well to the north and west of Boston, there is among adults a slightly different kind of love of country—less outspoken, perhaps, less defensive, but not casual and certainly appreciative. In those towns, too, children respond quite directly and sensitively to the various messages they have learned from their parents—and to a number of low-key “spectacles”: flags out on July Fourth; the deference of civil employees; pictures of father in uniform during one or another war; and perhaps most of all, conversations heard at the table. “My father hears bad news on television, and he says ‘thank God we’re Americans,’ ” says a girl of eleven. She goes on to register her mother’s gentle, thoughtful qualification: “It’s lucky we live where we do.”

Her mother’s sister, older and attracted to the cultural life only a city offers, has to live a more nervous life: “My aunt has huge locks on her doors. My mother leaves the keys right in the car.” Nevertheless, the United States of America, for the girl’s aunt as well as her parents, is nowhere near collapse: “Everything is going to be all right with the country. This is the best place to live in the whole world. That’s what my aunt says.” The girl pauses. Now is the time to ask her what she has to say. But she needs no prodding; immediately she goes on:

“No place is perfect. We’re in trouble now. The President and his friends, they’ve been caught doing bad things. It’s too bad. My older brother argues with daddy; he told daddy that it’s wrong to let the President get away with all he’s done, while everyone else has to go to jail; and he told daddy there’s a lot of trouble in the country, and no one is doing anything to stop the trouble. The President, I think he’s running as fast as he can from the police. I guess I would if I knew I’d done wrong. But I’d never be able to get to Egypt or Russia, so he’s lucky, that President.”

It is simply not altogether true, as most studies of “political socialization” conclude, that she and other children like her only tend to “idealize” the president, or give a totally “romanticized” kind of loyalty to the country, on the basis of what they hear, or choose to hear, from their parents or teachers. Many parents do select carefully what they say in front of their children; and children are indeed encouraged by their teachers, and the books they read, to see presidents and governors and supreme court justices and senators as figures much larger than life. Yet in no time—at least these days—children can lay such influences aside, much to the astonishment of even parents who don’t try to shield their children from “bad news” or “the evils of this world,” two ways of putting it one hears again and again.

Black children laugh at books given them to read in school, snicker while the teacher recites historical pieties which exclude mention of so very much, and often enough challenge their own parents when they understandably try to soften or delay the realization of what it has been like and will continue to be like for black people in America. White children, too, as James Agee noticed in the 1930s, pick up the hypocrisies and banalities about them and connect what they see or hear to a larger vision—a notion of those who have a lot and those who have very little at all.

“The President checks in with the people who own the coal company,” a miner’s shy son, aged eleven, remarked last spring in Harlan, Kentucky, where the Duke Power Company was fighting hard to prevent the United Mine Workers from becoming a spokesman of the workers. The child may well be incorrect; but one suspects that a log of the calls made by the President would show him in contact with people very much like those who are on the board of the Duke Power Company, as opposed to people like the boy’s parents.

By the same token, when a child whose father happens to be on the board of a utility company, or a lawyer who represents such clients, appears to overlook whatever critical remarks his or her parents have made about the United States and instead emphasizes without exception the nation’s virtues, including those of its leaders, by no means is a process of psychological distortion necessarily at work. The child may well have taken the measure of what has been heard (and overheard) and come to a conclusion: this is what they really believe, and just as important, the reason they believe what they say has to do with a whole way of life—the one we are all living. So, it is best to keep certain thoughts (in older people, called “views”) to myself, lest there be trouble.

Too complicated and subtle an analysis for a child under ten, or even under fifteen? We who in this century have learned to give children credit for the most astonishing refinements of perception or feeling with respect to the nuances of family life or the ups and downs of neighborhood play for some reason are less inclined to picture those same children as canny social observers or political analysts. No one teaches young children sociology or psychology; yet they are constantly noticing who gets along with whom, and why. If in school, or even when approached by a visitor with a questionnaire (or more casually, but no less noticeably, an all too interested face and manner), those same children tighten up and say little or nothing, or come up with remarks that are platitudes, pure and simple, they may well have come up with one of their sophisticated psychological judgments—reserving for another time the expression of any controversial political asides that may have come to mind.

As for some of those children who are a little different, who get called “rebellious” or “aggressive,” and sent off to guidance counselors or psychiatrists, they can occasionally help us know the thoughts of many other, more “normal” children—because someone under stress can under certain circumstances be unusually forth-coming. “My poor father is scared,” says the son of a rather well-to-do businessman, the owner of large tracts of Florida land, on which work, every year, hundreds of migrant farm workers, who, believe me, are also scared.

What frightens the boy’s father? His twelve-year-old namesake, who is described by his teachers as “a behavior problem”—he is, one gathers, fresh and surly at certain times—tries hard to provide an answer, almost as if whatever he comes up with will help him, too:

“I don’t know, but there will be times he’s sweating, and he’s swearing, and he’s saying he gave money to all those politicians, and they’d better do right by the growers, or they’ll regret it. Then he says he’s tired of living here, and maybe he should go back to Michigan where his grand-daddy was born. The other day the sheriff came by and said he didn’t know if he could keep those television people out indefinitely. So, daddy got on the phone to our senator, and we’re waiting. But it may cost us a lot, and we may lose. Daddy says we will either get machines to replace the migrants, or we’ll go broke, what with the trouble they’re beginning to cause. But I don’t think he really means it. He’s always threatening us with trouble ahead, my mother says, but you have to pour salt on what he says.”

That same boy scoffs at what he hears his teachers say about American history; one day he blurted out in class that his father had “coolies” working for him. Another time he said we’d had to kill a lot of Indians, because they had the land, and we wanted it, and they wouldn’t “bow to us, the way we wanted.” His teacher felt that she had witnessed yet another psychiatric outburst, but a number of his classmates did not. One of them, not especially a friend of his, remarked several days later, “He only said what everyone knows. I told my mother what he said, and she said it wasn’t so bad, and why did they get so upset? But she told me that sometimes it’s best to keep quiet, and not say a lot of things you think.”

It so happens that the child’s mother, speaking in front of her three sons, and without any evidence of shame or embarrassment, willingly picks up where she left off a day earlier with one of her boys:

“Yes, I feel we had to conquer Indians, or there wouldn’t be the America we all know and love today. I tell my children that you ought to keep your eye on the positive, accentuate it, you know, and push aside anything negative about this country. Or else we’ll sink into more trouble; and it’s been good to us, very good, America has.”

Her husband is also a grower. Her sons do indeed “idealize” America’s political system—but when a classmate begins to stir things up a little with a few blunt comments, there is no great surprise, simply the nod of recognition and agreement. And very important, a boy demonstrates evidence of moral development, a capacity for ethical reflection, even though both at home and at school he has been given scant encouragement to regard either migrants or Indians with compassion. Both Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg have indicated that cognitive and moral development in children have their own rhythm, tempo, and subtlety. Children ingeniously use every scrap of emotional life available to them as they develop “psychosexually,” and they do likewise as they try to figure out how (and for whom) the world works. A friend’s remarks, a classmate’s comments, a statement heard on television can give a child surprising moral perspective and distance on himself and his heritage—though, of course, he is not necessarily thereby “liberated” from the (often counter-vailing) day-to-day realities of, say, class and race.2

(This is the second part of a three-part article.)

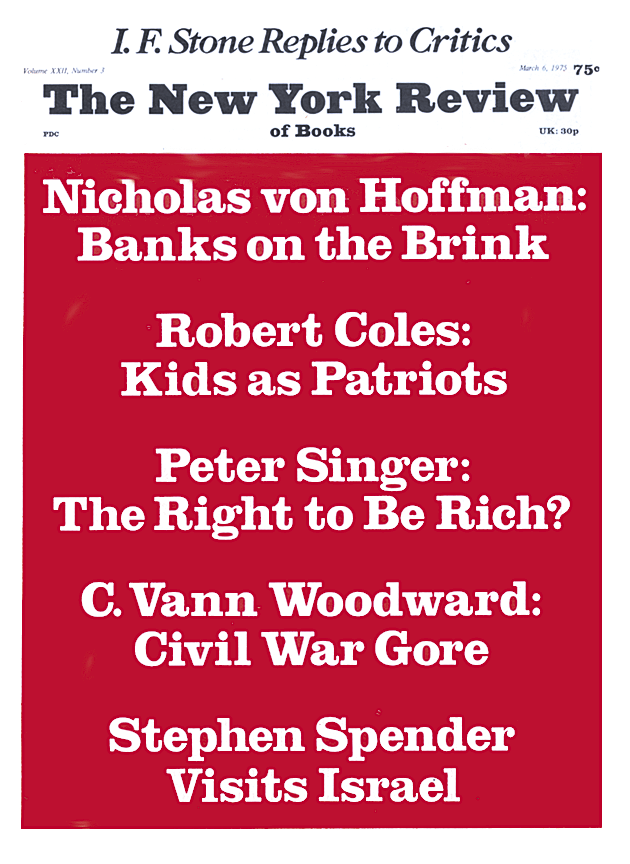

This Issue

March 6, 1975

-

1

There is nothing like a political crisis, however, to cause even such a child, among others, to have grave doubts about what is happening in the world around him. The recent and continuing racial tension in Boston has prompted apprehension and confusion in this white boy, who lives in South Boston, only three miles from its tragically unsettled high school. The boy lashes out at important elected officials, at newspapers and television stations—repeating what he has heard, but also, once in a while, coming up with idiosyncratic and illuminating flashes of social analysis, not to mention empathic generosity: ↩

-

2

Kohlberg’s work is especially helpful. Children come across, in his studies, as lively and thoughtful, as inclined to question and make critical moral judgments of various kinds, within limits set by their developing mental life. ↩