Boston, during the past winter and spring, offered Southerners a fistful of ironies. While schools in Mississippi’s Delta or the so-called Black Belt of Alabama, just over ten years ago the bastions of segregationist resistance to the civil rights movement, have been quietly desegregated for several years, Boston’s schools have been described by a federal court as deliberately and overwhelmingly segregated. Judge Garrity’s effort to change that state of affairs met with opposition that surely rivals the worst kind once experienced by black children in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi. Boston is a delicious object for Southern scorn, or serious or mock indignation. Boston, and its metropolitan area, is not just one of many Northern cities—though for some Southerners, one suspects, any evidence whatsoever of moral hypocrisy on the part of that nondescript group still called “Yankees” would be sufficient.

For well over a century the city has been regarded as among the nation’s educational and cultural leaders—one of the centers of abolitionist sentiment in the years before the Civil War,1 the capital city of the state whose sons both fought in large numbers against the Confederacy and went South after that war to rule in the name of a victorious federal government, and whose nationally known universities recently sent many students, faculty members, ministers, and aroused laymen to Selma and Montgomery, to the Mississippi Summer Project, the Delta Ministry, the medical program at Mound Bayou in Mississippi, the last for a long while directly affiliated with Tufts University. Black people in the rural parts of Mississippi or Alabama, who had heard through the grapevine (there is a constant return of departed kin for vacations, family crises, or celebrations) about the disadvantages of Detroit or Chicago, would often wonder about Boston: it must be different up there.

And to a degree it was. The city attracted in the earlier decades of this century only a small percentage of the black immigrants who left an impoverished and often brutal life in search of work and the relative sanctuary of a slum—no omnipotent and arbitrary sheriff, no Ku Klux Klan with its bonfires and its crazy talk and, sometimes, action. In Boston, as late as the 1940s, there wasn’t even a large black ghetto. Roxbury, now the heart of the city’s black section, was predominantly Jewish, with the Irish holding on firmly to one neighborhood. There were some old Boston black families; in certain ways they resembled the Brahmins. That is, blacks who were class conscious, who looked down on other blacks, who recited to anyone available how long it had been since they first arrived in the city. Malcolm X has described this vividly and with a proper measure of irony in his autobiography.

During and immediately after the Second World War, when those longtime black Bostonians and some more recent arrivals mostly lived in the South End, not far from white people, the city’s tensions were primarily religious and ethnic. John Roy Carlson, a muckraking reporter of the 1930s who specialized in exposing the plots of this country’s various right-wing groups, described Boston as then “the most anti-Semitic city in America” (Undercover, 1943). During and immediately after the Second World War synagogues were defaced, Jewish people hounded and molested. The newspapers first ignored, then played down the tension. There was, in addition, a substantial amount of tension between the city’s Irish and Italian population—with outbreaks at football games that went far beyond the realm of good-natured competitiveness. That trouble, too, went largely unreported. Boston continued to live off its nineteenth-century capital—the Athens of America—although, in fact, the city was badly decaying and apparently headed nowhere fast until the early 1950s.

But then a striking commercial boom took place, and with it a rise in Boston’s black population. In a few years blacks moved into all sections of Roxbury, into adjoining Dorchester, and beyond that to Mattapan. As they did so, the white population fled; it was a familiar and sad story—frightened people, manipulated by crafty real estate agents and loan sharks, all of whom, in turn, had the tacit support of the city’s banks, because the latter weren’t about to get involved in what they judged to be an unstable and fast-changing “market.” It was the Jews, primarily, who fled as the blacks advanced. The Irish were more reluctant, did leave Roxbury and parts of Dorchester, but have so far stood firm in other parts, protected by the city’s police in a way that the Jews would never be, or so many of them claimed as they left. Suddenly Boston had a “racial problem.” The tensions that had long existed between the Jews, Irish, and Italians seemed to vanish overnight. Now they were all white people, brothers under the skin.

Advertisement

The decades of distrust between the upper-class Yankees who ran the banks (and were heavily represented in the governing bodies of Harvard’s various schools) and the descendants of more recent immigrants never really has dissolved, but because those Yankees by and large live well outside the city, in towns like Dover, Sudbury, Concord, or Pride’s Crossing, no less, the tensions are more abstract—directed at names that have a history, and at institutions associated with those names, rather than at particular men and women who live in a visible neighborhood. In the words of a policeman whose beat is the streets of South Boston: “I used to hear my father talk about the Yankees as if he knew every one of them. He’d list all their crimes against the Irish. The worst crime was that they looked down on us, and just as bad, they owned everything and made sure we kept in our place—poor. But the Yankees have changed. They’ve slipped out of the city. I mean, they come in for their board meetings, and they check in with their offices, and a few of them still live on Beacon Hill, but most of them, from what I hear, are way out on farms, beyond the suburbs, and they don’t even try to make themselves known in the city. I guess they pull their weight, and they still have plenty of it, behind the scenes. And they still aim for the governor’s job.”

It wasn’t always that way, even fifty years ago, as he well knows. When James Michael Curley ran for mayor, as he did many times, he had specific Yankee political opponents, and set against him were prominent bankers or merchants whose self-assurance and tight-fisted probity lent themselves to a more mischievous caricature than J.P. Marquand ever had in mind. In fact Curley and other Irish politicians less gifted oratorically and less outspoken knew that “good works,” not to mention “good breeding,” are not inconsistent with economic exploitation, devious political chicanery, and the crudest kind of social arrogance and hypocrisy—even as, of course, those who have campaigned as reformers have shown themselves, on many occasions, to be not only crooks, but mean, hateful, and loud-mouthed troublemakers.

In any event, a policeman today in Boston has other tensions to worry about than those long-standing social tensions—the Yankee oligarchs as against the nouveau arrivistes. The city’s racial conflict has confronted the police, mostly Irish and obviously of working-class background, with serious tests of loyalty. They have had to restrain and even oppose the antibusing demonstrators and sometimes the riotous gestures of their own neighbors and kin. More broadly, they have had to stand against their own people.

The policeman quoted above uses that term often—“my people”; I have talked with his children on and off since 1967, and one of them has stayed in South Boston High School, at no small personal cost—vicious taunting from certain boycotting students and their families, who were intent on closing the school rather than letting it become peacefully desegregated. The policeman used to mean by “my people” the Irish of South Boston. Now the blacks have enabled him to include among his “people” Lithuanians, who also have lived in South Boston for many decades, and Italians, who live elsewhere but have made clear their support of ROAR (Restore Our Alienated Rights), which is made up of people against “forced busing.”

When he talks about that organization, and the dilemmas he has recently faced in the line of duty, he can be at least as pointed and thoughtful as Marx meant to be when, a long time ago, he used the word “alienation,” though the policeman is considerably more angry. The policeman feels shame because he has stood up to men and women he knows personally, thinks highly of, and regards as badly (sometimes willfully) misunderstood. By whom? By “the liberal media.” Who or what makes up that “media”? He is not completely sure, but he knows that Harvard sends its sons to work in that, “media,” and he is convinced it includes the Boston Globe, the city’s leading newspaper, as well as “all the people in educational television, with their fake English accents.”

The policeman also feels that his own situation, at times, is almost unbearable: “I have my beliefs, and then I have my job to do. It’s a lousy mess for me now. The people here don’t want this—they don’t want their kids going half-way across the city to no-good schools in a ghetto. Who keeps telling them they have to shut up and take whatever they’re told to take? I’ll tell you who: the federal judge, who lives out in fancy Wellesley, and the mayor, who has a townhouse on Beacon Hill and sends his own children to private schools, and the same old do-gooder crowd, who are always marching and giving sermons to other people. But when our own people march, they’re called ‘racists,’ and they’re ‘evading’ the judge’s court order, and all the rest. And who are they, the people pushing the judge to push us harder and harder? The NAACP—I don’t care about them. They think they’ve got to fight, fight—as if South Boston High School is Harvard, and they’ve got to get in! Well, let them fight!

Advertisement

“But the liberals from the suburbs and Beacon Hill and near Harvard Square, that’s another story. Who are they to deliver sermons to us? They sit out in their nice homes, on plenty of land, and they go to their offices or their libraries if they are professors, and they have their money stashed away, in case of an emergency, or for vacations.

“And where are their kids? I’ll tell you where: in private schools, that take in a few colored kids and call themselves ‘integrated’; or out in those suburban public schools, 99 percent white, and with no federal judge breathing down their backs.

“Then they call us ‘racists.’ Well, maybe we are. But I’d like to know who’s testing them, out there in suburbia? Who’s exposing the racism in affluent suburbia? Here you have my wife, trying to get part-time jobs, so we can keep out of debt, and we can’t. Here you have a lot of people without work. I know, I know—the colored don’t have jobs, either. But I’ll tell you who does have a job, and makes five or ten times what I do—they guy who calls the people in ROAR all kinds of bad names, and then slips out of some high-rise bank or office building in the downtown business center and shakes his head about South Boston. When he gets out of his car or off the train, he’s away from everything he doesn’t like, and he can shake his finger at us. A nice deal he’s got. If you have money you can afford to be generous—with other people’s children.”

That is a small sampling indeed of his thoughts and observations. He prays in church that he have the strength to obey his superiors and also be true to his conscience. He has definitely wished, occasionally, that his own “people” would not have said or done something. A crowd can all too easily become a mob—as he remembers in the case of the antiwar “people” who more than once had him frightened, amid slogans and obscenities he still recalls with agitated resentment. He was called a “pig” and worse by men and women who were against “violence”—Lyndon Johnson’s or Richard Nixon’s but, he adds, not their own.

Reluctantly, he acknowledges being witness to the same inclinations in “my own people.” He saw them set upon and almost kill a black man. He saw them turn on himself and other policemen when they tried to prevent a shouting, picketing mass of men and women from turning into a surging, frenzied avalanche, ready to overcome anyone and everything in its way. The horror he felt under those circumstances is exactly what Francis Russell had in mind when he gave his recent book the title of A City in Terror: 1919—The Boston Police Strike; and the “thin blue line” that Mr. Russell refers to as separating “civilization from chaos and anarchy” is a line many Boston policemen today have good reason to wonder and worry about.

Mr. Russell’s book, well written, full of shrewd social analysis and cultural history, is probably not going to be read by many of Boston’s policemen. But it provides what some of them, in moments of confusion or outright desperation, feel they most need: an account that gives perspective to today’s serious confrontations, and with it a certain ironic detachment. More than one Boston policeman has been reported anonymously in recent months as wondering out loud to reporters how the city’s current racial and educational crisis ever came about in the first place. And the particular policeman I know best constantly makes historical references, sociological observations, economic analyses. He rails against those with enough money and influence to protect themselves from the various pressures he and his neighbors continue to struggle with: a recession with its effect on the availability of work—two of his brothers are unemployed construction workers; a continuing inflation that eats away fixed salaries; and now, orders from a federal court that place him personally in a terrible bind, and reach into his family’s, his children’s everyday life.

As Mr. Russell tells us in his book, it was just such dilemmas that a previous generation of Boston policemen struggled with. After the First World War a mixture of recession and inflation also took hold. The police, mostly Irish, were under the control of a commissioner whom the author, in one of many understatements, describes as having “no great affection for the Boston Irish.” He lets William Allen White describe the police commissioner, Edwin Upton Curtis:

One of those solemn self-sufficient Boston heroes who apparently are waiting in the flesh to walk up the steps to a pedestal and be cast into monumental bronze. Boston parks are peopled with them. He embodied the spirit of traditional inherited skepticism about the capacity of democracy for self-government and a professed faith in the propertied classes’ ultimate right to rule.

Russell is wonderfully aware of the subtle but important distinctions of class and neighborhood that have been so much a part of Boston’s history. Curtis was what some in the city have called a “swamp Yankee”—not quite on top. So was Governor Calvin Coolidge looked down upon by other Coolidges in the city or in Cambridge. A more tolerant and self-assured Yankee might well have taken a different course, given in to the demand for a modest wage increase, and thereby averted the reluctantly undertaken effort of the police to organize a union and strike for their political and economic rights.

In fact, there was such a man, James Storrow, who tried vainly to mediate, placate, subdue tensions, and most of all avoid a series of decisions that would generate moralistic self-righteousness on both sides—the emotional precursor, he knew, of a bad and costly fight. But how had a man like Curtis become police commissioner in the first place? And the same question, only with respect to the governorship, holds for the tight-lipped, crafty, ever so agile Calvin Coolidge. Russell, a good social historian, struggles with the relationship between particular individuals and the larger, institutional forces that constantly come to bear on all of us.

In the second part of the epilogue to War and Peace Tolstoy showed how difficult it is to set down any one explanation for a particular event—a war, a strike, a riot. Certain people, he acknowledged, make themselves felt—upon occasion quite powerfully; but always there are those other influences that social historians document in relation to particular people or centuries: class and caste; laws, customs, and beliefs; money and political privilege. Any city’s police commissioner has to be almost exquisitely sensitive to all that—to the demands of the status quo, which it is his job to help maintain. We are told how and why Boston’s Edward Upton Curtis got his job almost inadvertently. Rich, important Yankee businessmen and bankers feared Boston’s immigrant masses, especially the Irish, who were beginning to exert themselves far too consistently and strongly. Curtis would keep watch on them, control over them.

Mr. Russell takes pains to let us know that after a point even rights and wrongs, the relative merit of longstanding grievances unfairly denied as against the claims of a city’s people that they be protected from anarchy, all get submerged in the “terror” (as he recalls it) of the moment, not to mention the bombast. And, as he shows us with diligence and a remarkable blend of distance and involvement (he clearly sympathizes with the strikers, but also with the frightened, mob-endangered ordinary citizens of the city), there are dozens of currents that one can, usually in retrospect, of course, connect to a particular tidal wave.

But there are degrees of importance; some currents are larger than others. In 1919 both the striking police and the ordinary (for a moment, unprotected) people of Boston were all too easily manipulated by a prejudiced, provincial, mean-spirited Curtis, by the exhortations and demands of newspaper publishers, bankers, merchants, by a calculating governor and his smallminded, selfish cronies. And inevitably, the “terror” was that of the policeman, hopelessly caught between deep and contradictory convictions, or that of the so-called man-in-the-street, trying to get by and often enough unable to do so. Those who determine the fate of the poor or the merely not-so-poor are the least vulnerable to any social crisis, even a police strike. The governor had his national guard, and the big businesses, we learn, had their private police.

What help is a book like Mr. Russell’s to those in Boston now caught up with at least a touch of the “terror” he describes? Or, for that matter, an impressively edited “historical anthology” of pieces on Boston called The Many Voices of Boston (Atlantic-Little, Brown), the work of Harvard’s Howard Mumford Jones and his wife Bessie Zaban Jones? The policeman I keep mentioning keeps mentioning something to me—that he can’t account for what is happening, but that he’d like to be able to do so; then, he could at least keep his cool under the most demanding, exhausting of circumstances.

And recently he has had additional reason to feel confused. The Boston newspapers have reported the results of the sociologist James Coleman’s latest study of school desegregation. It was Coleman’s first study, extensive and carefully done, that proponents of court-ordered integration found so helpful. He observed that black children profit a good deal educationally when they go to school with white children—and that poor, uneducated blacks don’t at all jeopardize the education of their white classmates who come from more affluent homes in which a motivation to study has taken root at an early age and been amply rewarded. Now Professor Coleman has felt compelled to study and take into account developments of the past five years. He has reported upon white flight in the wake of school desegregation, to such a degree that the schools involved have become once again all black. He has expressed himself loud and clear on the kind of situation Boston now faces. He has declared that “courts are the worst of all possible instruments for carrying out a very sensitive activity like integrating schools,” because they often fail to consider the twin sequelae that so often take place, at least in the larger cities: white flight and resegregation.

Coleman has even said that “the most important result” of his research is the finding that “the desegregation action of the courts in larger cities has been such as to speed the process by which central cities become black, and whites flee to the suburbs.” With respect to Boston, he has said this: “Boston is a peculiar kind of metropolitan area, with a large proportion of the metropolitan area outside the central city, including most middle-class whites. The desegregation order was, of course, limited to Boston proper, which meant that it involved primarily lower-class communities with strong ethnic ties, whites and blacks. Now under those circumstances, with most of the higher-achieving middle-class schools in the suburbs, one could hardly expect integration to have beneficial effects on achievement.”2

The people of South Boston and other sections of Boston have read and kept in mind those observations. In the words of the policeman: “What are we supposed to believe, when even a professor like that one says he has some second thoughts? Does our neighborhood, does our Boston, have to be destroyed because a judge is sitting there reading his law books and paying no attention to what’s been happening in this country, and because some NAACP lawyers, a lot of them real sharp white ones, who live in the suburbs themselves, and are hot out of Harvard Law School, keep on pushing the judge, and some editorial writers, who also live in the suburbs, keep saying the judge is right and the NAACP is right and we’re a bunch of ‘racists’?”

As for the black parents I have visited over the years in Roxbury, who are often without even high school diplomas, they have had to find in themselves enormous thoughtfulness and restraint. Many of them know that it is an ironic if not pyrrhic victory for their children or neighbors’ children to gain entrance to a school that is not unlike the schools near them—overcrowded, understaffed, badly equipped, and with low educational standards. (As a result, over a third of black people in Roxbury oppose busing.) One man told me, “The fight is not for South Boston High, the fight is bigger; we’re trying to get into America. Didn’t the Irish tight to get in? We’re going to fight and fight.”

An unemployed, uneducated, embittered and frustrated laborer, he might be called by someone interested in fitting a human being into economic “indices” or sociological categories. And, of course, similar worries plague both him and the policeman he would regard as an antagonist, even though the policeman recently has been protecting black children inside Boston’s schools and on its streets, and will probably have to do more of the same this autumn. And similar questions; each has a passion to know what went before them in Boston’s history—not to mention where they are going.

Mr. Russell and the Joneses have a lot of answers to such questions. We find out from their books about the many and different “terrors” that have been an inextricable part of Boston’s proud history, so much celebrated in this bicentennial year. We begin to understand, for example, why it was that Harvard’s president, A. Lawrence Lowell, politically conservative and no friend, certainly, of Catholics, Jews, or blacks, and Harvard’s professors and students, also by and large well-to-do and conservative, were so eager in 1919 to help patrol Boston’s streets3 rather than rally around a group of Irish Catholic policemen who earned scandalously low wages and had to endure outrageous working conditions—no pay increase for many years, a seven-day work week, with hours ranging from seventy-three to ninety-eight per week, and what Mr. Russell calls that “sorry conditions” of the police station houses, which were invariably dirty, overcrowded, and vermininfested. We begin to understand how hard it was, even so, for the police to go out on strike. They were conservative in social outlook, fiercely loyal to their country, their church, and as a result, fatally slow and shy in getting their case across to the public.

We also begin to understand how self-serving a crisis can be for certain politicians. The real culprit in presentday Boston’s trouble it its School Committee, to which, traditionally, some of the seediest and most conniving politicians in the city have for years sought and obtained election. The members of the committee get no pay, but there are plenty of contracts to vote on. One of them has been indicted this spring on a serious graft charge. For several two-bit School Committeemen the city’s racial conflict has been a welcome blessing. Their own failures to improve the schools have hurt Boston’s white and black children alike; but these are forgotten amid the hysteria and battle cries. Southern demagogues did the same thing for years. Similarly, Governor Calvin Coolidge could only profit from the police strike of 1919: stay out of it; let the various protagonists get burned and, inevitably, cancel each other out; come in at the end as a hero, the man who restores “law and order” with his state police and national guard—and the man who thereby had put himself on the road to the White House.

One of the essays the Joneses have included in their book is by the historian Ray Allen Billington, “The Burning of the Charlestown Convent,” originally published almost four decades ago (March 1937) in The New England Quarterly. Billington refers to “class antipathies, religious jealousies and economic conditions” as responsible for a “state of mind” which preceded and for that matter persisted after the riotous assault on a Catholic convent. In fact, throughout the Joneses’ various excerpts one comes across accounts of hatred, fear, envy, rivalry, exploitation. There were (and are) fine and decent moments. But Boston (and not it alone) has never for long, it seems, been able to free itself of the three things Mr. Billington mentions.

Today, one has to add a fourth, racial hostility. For many blacks the reminders that there have been malice, bitterness, distrust, recurrent outbreaks of violence, even riots for centuries now in Boston are of little comfort. Besides, they insist, the experience of being black in Boston is altogether special; yes, others have known discrimination and exploitation, but blacks are not only on the bottom economically, but excluded socially and in large measure (through gerrymandering) denied politically.

Why now, I hear blacks ask, do our various scholars suddenly come up with a plea for an understanding of the contemporary problems and past difficulties encountered by working-class whites of various backgrounds—at just the moment when blacks are trying to break out of ghettoes, obtain better jobs, send their children to better schools? It is not all that hard to mobilize sympathy for people who have rioted, displayed hate, even committed arson and taken lives. As Mr. Billington indicates at great length, those who set fire to the convent in 1834 were not only hateful and violent but vulnerable, poor, frightened people.

“For the most part they were truckmen or brickmakers,” he tells us, fundamentalist Protestants who were looked down upon (and economically exploited) by the upper middle class, more “liberal” Protestants of the day—who, interestingly enough, preferred to send their children to private Catholic schools rather than have them exposed to the “lower orders” of Boston, whose religious beliefs and values were reflected in the Boston public schools.

But compassion, too, can have its reasons. If Boston’s blacks are suspicious of one kind of compassion, the city’s whites have their doubts about another kind. Why, I hear asked over and over again in South Boston, do “Harvard liberals” or “suburban reformers” find it—in the policeman’s words—“so wonderful to send their kids abroad, to the Peace Corps, or to Roxbury, to help the colored, but here—they stay away, and in their fancy parlors they haven’t got a good word for us.” He goes on, “All they do is point their fingers. But boy, can they find sympathy for others—jailbirds, crazy people, all kinds of fanatics, people who fight against our country and kill our own soldiers.”

One of those soldiers, still “missing” in Vietnam, was his oldest son. In that connection, when a visitor like me tries to demonstrate a degree of the “sympathy” the policeman is skeptical about, the result is, at best, a moment of awkwardness. The visitor has every reason to worry about being condescending and being removed from certain everyday, concrete (and burdensome) conditions of life, even as, obviously, the same reason for worry gets going during visits to Roxbury, where in no uncertain terms one is reminded that blacks, whatever their past, or even their present, have had and do have and seemingly will continue to have an utterly special fate in this country: when it has lasted so long, harsher oppression becomes a qualitatively different degree of exclusion.4

Nor does it help very much to try to be the open, generous “friend,” and, later, “interpreter.” One can talk about books like Francis Russell’s or that put together by the Joneses: One can try to remind the policeman, or his black counterpart, that nostalgia notwithstanding, Boston was an infinitely more violent and crude place in the nineteenth century, that each “group” had to struggle hard as it moved from acquiescence to assertion. One can say that the police have a much better deal than they did in 1919, that Harvard has changed enormously since then, that Boston’s liberals or its Brahmins are as diverse as people in other groups, and therefore done an injustice when subjected to sweeping generalizations, and on and on.

But the policeman is in the middle of a “war,” as he calls it sometimes when he is upset. If there are moments when he is inclined toward the long view, most of the time he has all he can do to keep his private thoughts to himself, get through a day without quitting the force or making a bad mistake and being fired. (And he acknowledges openly that some of his colleagues do make bad mistakes, and don’t get fired—as a number of blacks have reason to know.) He is afraid, he says, that if he starts “thinking about all this trouble here too much,” he’ll collapse: “I can’t do that. I’d be paralyzed. I’d quit. And I don’t have a Boston trust fund to keep me going while I find another job or do my thinking!”

And so with the black parents in Roxbury, or the white parents in South Boston; they are, again, by their own repeated description, caught up in serious, bitter “war” or “fight.” When someone like me adds, to himself or to them, hopelessly caught up, he is revealing his true colors, not only his judgment, his detachment, but his position as a privileged outsider who fears the prospect of more conflict ahead. No wonder the policeman once asked whether there had been any studies of “rich, noisy liberals,” whether their envies, prejudices, resentments, hypocrisies had been recorded.

One all too easily dismisses such a line of reasoning: an evasion of the issue, a refusal to come to terms with the real purposes of a federal court order, a resort to class-consciousness, when the issue is explicit racism. But the question lingers, stands on its own merits apart from the motivation that may have impelled it, stands as one of many reminders that Boston contains not only Mr. Russell’s “thin blue line” dividing “civilizations” from “anarchy” but other “lines” too: ones the black people of Roxbury have always known about, and the poor and working-class white people of South Boston are now talking about—“lines” that some of us who write articles and books or read them as a matter of course may out of privilege be able to ignore.

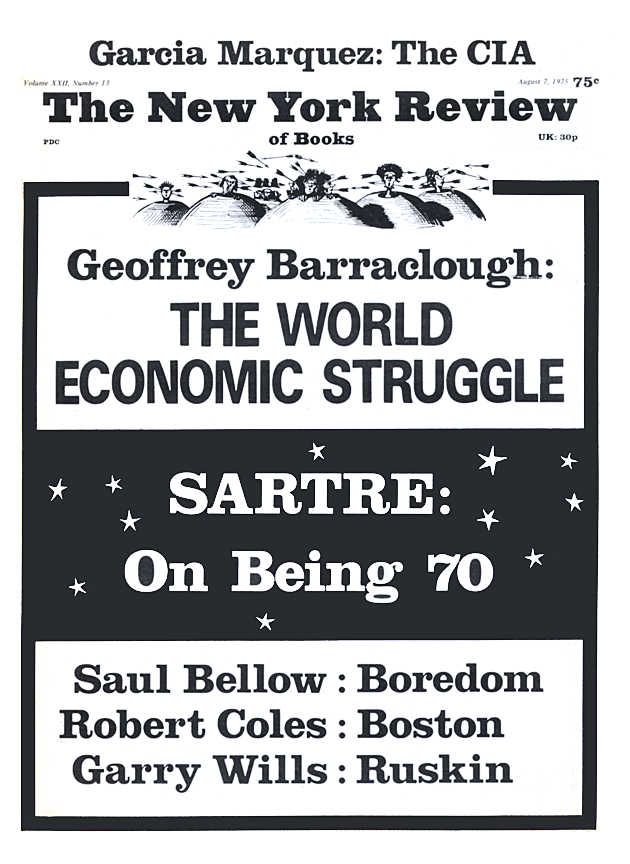

This Issue

August 7, 1975

-

1

In fact, abolitionists in Boston were attacked in the street by working people and badly snubbed by the city’s well-to-do. It wasn’t any easier for Garrison or Richard Henry Dana or Charles Sumner to stand up for the blacks than it was for many brave but ostracized white people of the South to do so before and during the civil rights struggle of the 1960s. See David H. Donald’s Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War. ↩

-

2

Mr. Coleman has even allowed his conclusions to be entered as evidence in a last-ditch court effort by those opposed to the federal judge’s decision in favor of busing. And a thoughtful reply to Coleman’s findings, made by Professors Robert Green and Thomas Pettigrew, both well-known race-relations scholars, went virtually unnoticed for a while by the Boston newspapers. ↩

-

3

In contrast, few Harvard students hastened to enlist in the Union army when the Civil War started. ↩

-

4

An especially fine and poignant statement of the case is made by the Agnes Moreland Jackson in her “Challenge to All White Americans or, White Ethnicity from a Black Perspective ” in Sounding, Spring, 1973. ↩