Some years ago a friend remarked to a brand-new President’s wife (a woman of unique charm, wit, sensibility, and good grooming) that there was no phrase in our language which so sets the teeth on edge as “First Lady.”

“Oh, how true!” said that lady, after the tiniest of pauses. “I keep telling the operators at the White House not to call me that, but they just love saying ‘First Lady.’ And of course Mrs. E********* always insisted on being called that.”

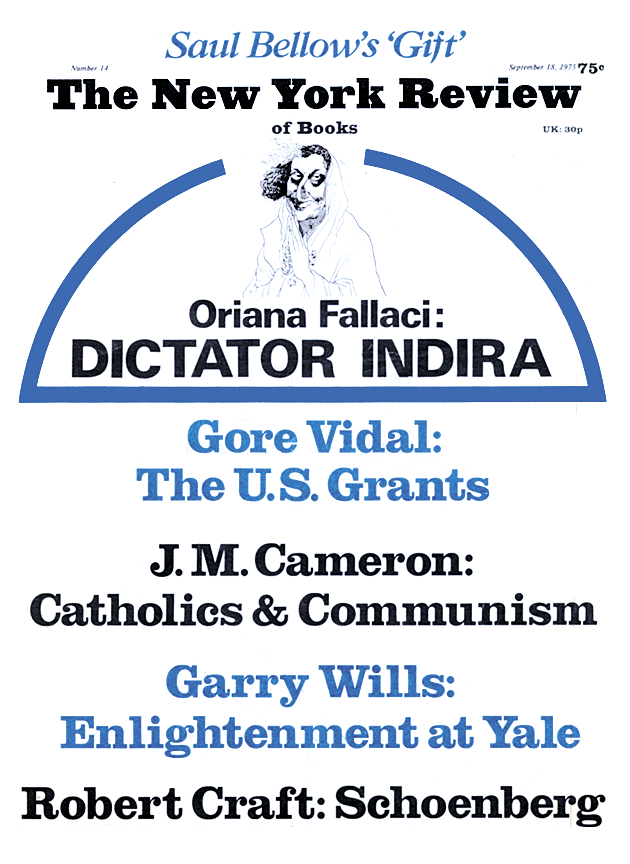

According to one Ralph Geoffrey Newman, in a note to the recently published The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant, “the term ‘First Lady’ became a popular one after the production of a comedy, The First Lady in the Land…December 4, 1911.” The phrase was in use, however, as early as, the Ladyhood of Mrs. Rutherford B. (“Lemonade Lucy”) Hayes.

Martha Washington contented herself with the unofficial (hence seldom omitted) title “Lady” Washington. Mrs. James Monroe took a crack at regal status, receiving guests on a dais with something suspiciously like a coronet in her tousled hair. When twenty-four-year-old Miss Julia Gardiner of Gardiners Island became the doting wife of senior citizen John Tyler, she insisted that his stately arrivals and departures be accompanied by the martial chords of “Hail to the Chief.” Mary Todd Lincoln often gave the impression that she thought she was Marie Antoinette.

It is curious that a Johnny-come-fairly-lately republic like the United States should so much want to envelop in majesty those for the most part seedy political hacks quadrennially “chosen” by the people to rule over them. As the world’s royalties take to their bicycles—or to their heels—the world’s presidents from Giscard to Leone to our own dear sovereign affect the most splendid state. I am certain that had Mr. and Mrs. Richard M. Nixon of San Clemente, California and Key Biscayne, Florida continued in residence at the White House we would by now not only have grown used to those silver trumpets that herald the approach of the President but the park in front of the White House would daily be made colorful with the changing of the guard, consisting of chosen members of the CIA and FBI in green berets, bullet-proof vests, and armed with the latest listening devices.

It would seem to be a rule of history that as the actual power of a state declines, the pageantry increases. Certainly the last days of the Byzantine empire were marked by a court protocol so elaborate and time-consuming that the arrival of the Turks must have been a great relief to everyone. Now, as our own imperial republic moves gorgeously into its terminal phase, it is pleasant and useful to contemplate two centuries of American court life, to examine those personages who have lived in the White House and borne those two simple but awful titles “The President,” “The First Lady,” and, finally, to meditate on that peculiarly American religion, President-worship.

The Eighteenth President Ulysses Simpson Grant and his First Lady Julia Dent Grant are almost at dead center of that solemn cavalcade which has brought us from Washington to Ford, and in the process made a monkey of Darwin. Since 1885 we have had Grant’s own memoirs to study; unfortunately, they end with the Civil War and do not deal with his presidency. Now Julia Dent Grant’s memoirs have been published for the first time and, as that ubiquitous clone of Parson Weems Mr. Bruce Catton says in his introduction, she comes through these pages as a most “likable” woman. “No longer is she just Mrs. Grant. Now she has three dimensions.”

From her own account Julia Dent Grant does seem to have been a likable, rather silly woman, enamored of First Ladyhood (and why not?), with a passion for clothes. If photographs are to be trusted (and why should they be when our Parson Weemses never accept as a fact anything that might obscure those figures illuminated by the high noon of Demos?), Julia was short and dumpy, with quite astonishingly crossed eyes. As divinity in the form of First Ladyhood approached, Julia wanted to correct with surgery nature’s error but her husband very nicely said that since he had married her with crossed eyes he preferred her to stay the way she was. In any case, whatever the number of Julia’s dimensions, she is never anything but Mrs. Grant and one reads her only to find out more about that strange enigmatic figure who proved to be one of our country’s best generals and worst presidents.

Grant was as much a puzzle to contemporaries as he is to us now. To Henry Adams, Grant was: “preintellectual, archaic, and would have seemed so even to the cave-dwellers.” Henry Adams’s brother had served with Grant in the war and saw him in a somewhat different light. “He is a man of the most exquisite judgment and tact,” wrote Charles Francis Adams. But “he might pass well enough for a dumpy and slouchy little subaltern, very fond of smoking.” C.F. Adams saw Grant at his best, in the field; H. Adams saw him at his worst, in the White House.

Advertisement

During Grant’s first forty years of relative failure, he took to the bottle. When given command in the war, he seems to have pretty much given up the booze (though there was a bad tumble not only off the wagon but off his horse at New Orleans). According to Mr. Bruce Catton, “It was widely believed that [Grant], especially during his career as a soldier, was much too fond of whiskey, and that the cure consisted in bringing Mrs. Grant to camp; in her presence, it was held, he instantly became a teetotaler…. This contains hardly a wisp of truth.” It never does out there in Parson Weems land where all our presidents were good and some were great and none ever served out his term without visibly growing in the office. One has only to listen to Rabbi Korff to know that this was true even of Richard M. Nixon. Yet there is every evidence that General Grant not only did not grow in office but dramatically, spectacularly shrank.

The last year of Grant’s life was the noblest, and the most terrible. Dying of cancer, wiped out financially by a speculator, he was obliged to do what he had always said he had no intention of doing: write his memoirs in order to provide for his widow. He succeeded admirably. The two volumes entitled Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant earned $450,000; and Julia Grant was able to live in comfort for the seventeen years that she survived her husband. Now for the first time we can compare Grant’s memoirs with those of his wife.

With the instinct of one who knows what the public wants (or ought to get), Grant devoted only thirty-one pages to his humble youth in Ohio. The prose is Roman—lean, rather flat, and, cumulatively, impressive. Even the condescending Matthew Arnold allowed that Grant had “the high merit of saying clearly in the fewest possible words what had to be said, and saying it, frequently, with shrewd and unexpected turns of expression.” There is even a quiet wit that Grant’s contemporaries were not often allowed to see: “Boys enjoy the misery of their companions, at least village boys in that day did” (this is known as the Eisenhower qualification: is it taught at West Point? in order to confuse the press?), “and in later life I have found that all adults are not free from this peculiarity.”

The next 161 pages are devoted to West Point and to Grant’s early career as a professional army officer. Grant’s eyes did not fill with tears at the thought of his school days on the banks of the Hudson. In fact, he hated the Academy: “early in the session of the Congress which met in December, 1839, a bill was discussed abolishing the Military Academy. I saw this as an honorable way to obtain a discharge…for I was selfish enough to favor the bill.” But the Academy remained, as it does today, impregnable to any Congress.

On graduation, Second Lieutenant Grant was posted to Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis, where, he noted, “too many of the older officers, when they came to command posts, made it a study to think what orders they could publish to annoy their subordinates and render them uncomfortable.”

Grant also tells us, rather casually, that “At West Point I had a classmate…F.T. Dent, whose family resides some five miles west of Jefferson Barracks….” The sister of the classmate was Julia Dent, aged seventeen. According to Grant, visits to the Dent household were “enjoyable.” “We would often take long walks, or go on horseback to visit the neighbors…. Sometimes one of the brothers would accompany us, sometimes one of the younger sisters.”

In May 1844, when it came time to move on (the administration was preparing an interdiction or incursion of Mexico), Grant writes: “before separating [from Julia] it was definitely understood that at a convenient time we would join our fortunes….” Then Grant went off to his first war. Offhandedly, he gives us what I take to be the key if not to his character to his success: “One of my superstitions had always been when I started to go any where, or to do anything, not to turn back, or stop until the thing intended was accomplished.” This defines not only a certain sort of military genius, but explains field-commander Grant who would throw wave after wave of troops into battle, counting on superior numbers to shatter the enemy while himself ignoring losses.

Advertisement

When Henry Adams met Grant at the White House, he came away appalled by the torpor, the dullness of the sort of man “always needing stimulants, but for whom action was the highest stimulant—the instinct of fight. Such men were forces of nature, energies of the prime….” This was of course only partly true of Grant, in whom the moral sense was not entirely lacking. Unlike so many American jingoes, Grant did not like war for its own bloody self or conquest for conquest’s sake. Of the administration’s chicanery leading up to the invasion of Mexico, he wrote with hard clarity, “I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation…. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.” The Berrigans could not have said it better.

Grant also had a causal sense of history that would have astonished Henry Adams had he got to know the taciturn and corrupted, if not corrupt president. Of the conquest of Mexico and the annexation of Texas, Grant wrote, “To us it was an empire and of incalculable value; but it might have been obtained by other means. The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican War. Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times.” If Grant’s law still obtains, then the only hope for today’s American is emigration.

The Grant of those youthful years seems most engaging (but then we are reading his own account). He says firmly, “I do not believe that I ever would have the courage to fight a duel.” He was probably unique among military commanders in disliking dirty stories, while “I am not aware of ever having used a profane expletive in my life; but I would have the charity to excuse those who may have done so, if they were in charge of a train of Mexican pack mules….”

Grant saw right through the Mexican war, which “was a political war, and the administration conducting it desired to make party capital of it.” Grant was also very much on to the head of the army General Scott, who was “known to have political aspirations, and nothing so popularizes a candidate for high civil positions as military victories.” It takes one, as they say, to know another.

Mark Twain published Grant’s memoirs posthumously, and one wonders if he might have added a joke or two. Some possible Twainisms: “My regiment lost four commissioned officers, all senior to me, by steamboat explosions during the Mexican war. The Mexicans were not so discriminating. They sometimes picked off my juniors.” The cadence of those sentences reveals an expert sense of music-hall timing. When a Mexican priest refused to let Grant use his church during an engagement, Grant threatened the priest with arrest. Immediately, the man “began to see his duty in the same light that I did, and opened the door, though he did not look as if it gave him special pleasure to do so.” But whether or not Twain helped with the jokes, it must be remembered that the glum, often silent, always self-pitying president was capable, when he chose, of the sharp remark. Told that the brilliant but inordinately vain Senator Charles Sumner did not believe in the Bible, Grant said, “That’s only because he didn’t write it.”

The Mexican war ended, and “On the twenty-second of August, 1848, I was married to Miss Julia Dent Grant, the lady of whom I have before spoken.” With that Caesarian line, the lady appears no more in the two volumes dedicated to the fighting of the Civil War. Now Julia’s memoirs redress the balance.

In old age, Julia put pen to paper and gave her own version of her life and marriage, but for one reason or another she could never get the book published. Now, at last, her memoirs are available, suitably loaded with a plangent introduction by Mr. Catton (“they shared one of the great, romantic, beautiful loves of all American history”), a note by R.G. Newman on “The First Lady as an Author,” and a foreword and notes by J.Y. Simon. The notes are excellent and instructive.

In her last years Julia was not above hawking her manuscript to millionaire acquaintances; at one point she offered the manuscript to book-lover Andrew Carnegie for $125,000. Just why the book was never published is obscure. I suspect Julia wanted too much money for it; also, as she wrote in a letter, the first readers of the text thought it “too near, too close to the private life of the Genl for the public, and I thought this was just what was wanted.” Julia was right; and her artless narrative does give a new dimension (if not entirely the third) to one of the most mysterious (because so simple?) figures in our history.

“My first recollections in life reach back a long way, more than three-score years and ten now. We, my gentle mother and two little brothers, were on the south end of the front piazza at our old home, White Haven.” Julia sets us down firmly in Margaret Mitchell country. “Life seemed one long summer of sunshine, flowers, and smiles to me and to all at that happy home.” Mamma came from “a large eastern city,” and did not find it easy being “a western pioneer’s wife.” The darkies were happy as can be (this was slave-holding Missouri) and “I think our people were very happy. At least they were in mamma’s time, though the young ones became somewhat demoralized about the beginning of the Rebellion, when all the comforts of slavery passed away forever.”

Julia was obviously much indulged. “Coming as I did to the family after the fourth great boy, I was necessarily something of a pet…. It was always, ‘Will little daughter like to do this?’ ‘No!’ Then little daughter did not do it.” I suspect that little daughter’s alarmingly crossed eyes may have made the family overprotective. She herself seems unaware of any flaw: “Imagine what a pet I was with my three, brave, handsome brothers.” She was also indulged in school where she was good in philosophy (what could that have been?), mythology, and history, but “in every other branch I was below the standard, and, worse still, my indifference was very exasperating.” Although Julia enjoys referring to herself as “poor little me,” she sounds like a pretty tough customer.

Enter Lieutenant Grant. Julia’s description of their time together is considerably richer than that of the great commander. “Such delightful rides we all used to take!” So far her account tallies with his. But then, I fear, Julia falls victim to prurience: “As we sat on the piazza alone, he took his class ring from his finger and asked me if I would not wear it…. I declined, saying, ‘Oh, no, mamma would not approve….’ ” “I, child that I was, never for a moment thought of him as a lover.” He goes. “Oh! how lonely it was without him.” “I remember he was kind enough to make a nice little coffin for my canary bird and he painted it yellow. About eight officers attended the funeral of my little pet.” When Grant came back to visit, Julia told him “that I had named one of my new bedstead posts, for him.” Surely the good taste of the editor might have spared us this pre-Freudian pornography. In any case, after this shocker, Julia was obliged to marry Grant…or “Ulys” as she called him.

“Our station at Detroit is one pleasant memory…gay parties and dinners, the fêtes champêtres…. Our house was very snug and convenient: two sitting rooms, dining room, bedroom, and kitchen all on the first floor.” (And all of this on a captain’s pay). Julia’s especial friend that winter was the wife of Major John H. Gore. Together they gave a fancy dress ball on a Sunday, invoking the wrath of the Sabbatarians. But the girls persisted and Mrs. Gore came as the Sultana of Turkey while “I, after much consideration, decided upon the costume of the ideal tambourine girl…. Ulys called me ‘Tambourina’ for a long time afterwards.”

But then Grant left the army; and the descent began. “I was now to commence,” he wrote, “at the age of thirty-two, a new struggle for our support.” Like most professional army men Grant was fitted for no work of any kind save the presidency and that was not yet in the cards. “My wife had a farm near St. Louis; to which we went, but I had no means to stock it.” Nevertheless, “I managed to keep along very well until 1858, when I was attacked by fever and ague.” Perhaps he was; he was also attacked by acute alcoholism.

But the innumerable clones of Parson Weems tend to ignore any blemish on our national heroes. And Julia does her part, too. She writes, “I have been both indignant and grieved over the statement of pretended personal acquaintances of Captain Grant at this time to the effect that he was dejected, low-spirited, badly dressed, and even slovenly.” “Low-spirited” is a nice euphemism for full of spirits. Julia had the Southern woman’s loyalty to kin: protect at all costs; and ignore the unpleasant. She even goes beyond her husband’s dour record, declaring, “Ulys was really very successful at farming…and I was a splendid farmer’s wife.”

Julia’s family loyalty did not extend to Ulys’s folks. Although Ulys and the Dent family could do no wrong, the Grants were generally exempted from her benign policy. In fact, Julia loathed them. “I was joyous at the thought of not going to Kentucky, for the Captain’s family, with the exception of his mother, did not like me…; we were brought up in different schools. They considered me unpardonably extravagant, and I considered them inexcusably the other way and may, unintentionally, have shown my feelings.” There were also political disagreements between the two families as the Civil War approached. The Dents were essentially Southern, and Julia “was a Democrat at that time (because my father was)…. I was very much disturbed in my political sentiments, feeling that the states had a right to go out of the Union if they wished to.” But she also thought that the Union should be preserved. “Ulys was much amused at my enthusiasm and said I was a little inconsistent when I talked of states’ rights.”

With the coming of the Civil War, the lives of the Grants were never again to be private. Rapidly he rose from Illinois colonel (they had moved to Galena) to lieutenant general in command of the Union forces. The victories were splendid. Julia had anxious moments, not to mention innumerable prophetic dreams which she solemnly records.

At one point, separated from the General, “I wept like a deserted child.… Only once again in my life—when I left the White House—did this feeling of desertion come over me.” There were also those unremitting base rumors. Why, “The report went out,” on some crucial occasion, “that General Grant was not in the field, that he was at some dance house. The idea! Dear Ulys! so earnest and serious; he never went to a party of any kind, except to take me.” Julia’s usual euphemism for the drunken bouts was “he was ill.” And she always helped him get well.

Grant was not above making fun of her. Julia: “Ulys, I don’t like standing stationary washstands, do you?” Ulys: “Yes, I do; why don’t you?” Julia: “Well, I don’t know.” Ulys: “I’ll tell you why. You have to go to the stand. It cannot be brought to you.”

Midway through the war, some Southern friends were talking of “the Constitution, telling me the action of the government was unconstitutional. Well, I did not know a thing about this dreadful Constitution and told them so…. I would not know where to look for it even if I wished to read it…. I was dreadfully puzzled about the horrid old Constitution.” She even asked her father: “Why don’t they make a new Constitution since this is such an enigma—one to suit the time.” I suspect Julia was pretty much reflecting her husband’s lifelong contempt for a Constitution that he saw put aside in the most casual way by Abraham Lincoln, who found habeas corpus incompatible with national security. But although neither Grant nor Julia was very strong on the Bill of Rights, she at least had a good PR sense. When “General Grant wrote that obnoxious order expelling the Jews from his lines for which he was so severely reprimanded by the federal Congress—the General said deservedly so, as he had no right to make an order against any special sect.”

In triumph, Julia came east after Ulys assumed command of the armies. Julia was enchanted by the White House and President Lincoln, in that order. Mrs. Lincoln appears to have been on her worst behavior and Julia has a hard time glossing over a number of difficult moments. On one occasion, Julia plumped herself down beside the First Lady. Outraged, Mrs. Lincoln is alleged to have said, “How dare you be seated, until I invite you?” Julia denies that this ever happened. But she does describe a day in the field when Mrs. Lincoln was upset by a mounted lady who seemed to be trying to ride beside President Lincoln. As one reads, inevitably, in the vast spaces between the lines of Julia’s narrative, it would seem that Mrs. Lincoln went absolutely bananas, “growing more and more indignant and not being able to control her wrath….” But, fortunately, Julia was masterful—“I quietly placed my hand on hers”—and was soothing.

Later, when the presidential yacht was in the James River, close to Grant’s headquarters, Julia confesses that “I saw very little of the presidential party now, as Mrs. Lincoln had a good deal of company and seemed to have forgotten us. I felt this deeply and could not understand it…. Richmond had fallen; so had Petersburg. All of these places were visited by the President and party, and I, not a hundred yards from them, was not invited to join them.”

Despite the dresses, the dreams, the self-serving silly-little-me talk, Julia has a sharp eye for detail; describing Richmond, the last capital of the Confederacy, she writes: “I remember that all the streets near the public buildings were covered with papers—public documents and letters, I suppose. So many of these papers lay on the ground that they reminded me of the forest leaves when summer is gone.”

Although Grant ignores such details he is shrewd not only about his colleagues but about his former colleagues, the West Pointers who led the Confederate army. He writes of Jefferson Davis with whom he had served in Mexico: “Mr. Davis had an exalted opinion of his own military genius…. On several occasions during the war he came to the relief of the Union army by means of his superior military genius.” Grant also makes the Cromwellian assertion: “It is men who wait to be selected, and not those who seek, from whom we may always expect the most efficient service.”

Although never a Lincoln man in politics, Grant came to like the President, and would listen respectfully to Lincoln’s strategic proposals, refraining from pointing out their glaring flaws. Grant also took seriously Secretary of War Stanton’s injunction never to tell Lincoln his plans in advance because the President is “so kind-hearted, so averse to refusing anything asked of him, that some friend would be sure to get from him all he knew.” Lincoln was plainly aware of this defect because he “told me he did not want to know what I proposed to do.”

At about this time the press that was to be Grant’s constant, lifelong bête-noir began to get on his nerves. The New York Times was a particular offender; grimly, Grant remarked on that portion of the press which “always magnified rebel successes and belittled ours.” In fact, “the press was free up to the point of treason.”

Grant had great respect for the Confederate army, and in retrospect lauded the Fabian tactics of General J.E. Johnston on the ground that “anything that could have prolonged the war a year beyond the time that it did finally close, would probably have exhausted the North to such an extent that they might then have abandoned the contest and agreed to a separation.” Because “the South was a military camp, controlled absolutely by the government with soldiers to back it,…the war could have been protracted, no matter to what extent the discontent reached….” Yet the kindly Lincoln had already suspended habeas corpus. One suspects that if Grant had been the president, he would have shut down the press, sent Congress home, and made the North an armed camp.

Grant had much the same lifelong problem with the “horrid old Constitution” that Julia had. Magisterially, he writes, “The Constitution was not framed with a view to any such rebellion as that of 1861-5. While it did not authorize rebellion it made no provision against it. Yet the right to resist or suppress rebellion is as inherent as the right of self defense….” Accepting this peculiar view of that intricate document, Grant noted with some satisfaction that “the Constitution was therefore in abeyance for the time being, so far as it in any way affected the progress and termination of the war.” During Grant’s presidency, the Constitution was simply an annoyance to be circumvented whenever possible. Or as he used to say when he found himself, as president, blocked by mere law, then “Let the law be executed.”

On that day when lilacs in the dooryard bloomed, Julia was in Washington preparing to go with Grant to Philadelphia. At noon, a peculiar-looking man rapped on her door. ” ‘Mrs. Lincoln sends me, Madam, with her compliments, to say she will call for you at exactly eight o’clock to go to the theater.’ To this, I replied with some feeling (not liking either the looks of the messenger or the message, thinking the former savored of discourtesy and the latter seemed like a command), ‘You may return with my compliments to Mrs. Lincoln and say I regret that as General Grant and I intend leaving the city this afternoon, we will not, therefore, be here….’ “

It is nice to speculate that if Mrs. Lincoln had asked Julia aboard the yacht that day in the James River, there might never have been a Grant administration. Julia has her own speculation: “I am perfectly sure that he [the messenger], with three others, one of them [John Wilkes] Booth himself, sat opposite me and my party at luncheon.”

That night in Philadelphia they heard the news. “I asked, ‘This will make Andy Johnson President, will it not?’ ‘Yes,’ the General said, ‘and for some reason, I dread the change.’ ” Nobly, Julia did her duty: “With my heart full of sorrow, I went many times to call on dear heart-broken Mrs. Lincoln, but she could not see me.”

After commanding the armies in peacetime and behaving not too well during that impasse between President Johnson and Secretary of War Stanton which led to Johnson’s impeachment, Grant was himself nominated for the presidency and won a great victory. Although, unhappily, Grant’s own memoirs stop with the war, Julia’s continue gaily, haphazardly, and sometimes nervously through that gilded age at whose center these two odd little creatures presided.

Until our own colorful period, nothing quite like the Grant administration had ever happened to the imperial republic. In eight years almost everyone around Grant was found to be corrupt from his first vice president Colefax to his brother-in-law to his private secretary to his secretary of war to his minister to Great Britain; the list is endless. Yet the people forgave the solemn little man who had preserved the Union and then proposed himself to a grateful nation with the phrase “Let us have peace.”

Grant was re-elected president in 1872, despite a split in the Republican party; the so-called Liberal Republicans supported Horace Greeley as did the regular Democrats. Although the second terms was even more scandalous than the first, the Grants were eager for yet a third term. But the country was finally fed up with Grantism. In the centennial summer of 1875, at the Philadelphia exhibition, President Grant had the rare experience of being booed in public. Julia does not mention the booing. But she does remember that the Empress of Brazil was asked to start the famous Corliss engine, while “I, the wife of the President of the United States—I, the wife of General Grant—was there and was not invited to assist at this little ceremony…. Of this I am quite sure: if General Grant had known of this intended slight to his wife, the engine never would have moved with his assistance.”

Nevertheless, after four years out of office General and Mrs. Grant were again eager to return to the White House, to “the dear old house…. Eight happy years I spent there,” wrote Julia, “so happy! It still seems as much like home to me as the old farm in Missouri, White Haven.” But it looked rather different from the farm or, for that matter, from the way the White House has usually looked. By the time Mrs. Grant had finished her refurbishments, the East Room was divided into three columned sections and filled with furniture of ebony and gold. Julia was highly pleased with her creation; in fact, “I have visited many courts and, I am proud to say, I saw none that excelled in brilliancy the receptions of President Grant.”

Except for a disingenuous account of the secretary of war’s impeachment (his wife “Puss” Belknap was a favorite of Julia’s), the First Lady herself hardly alludes to the scandals of those years. On the other hand, Julia describes in rapturous detail her trip around the world with Ulys. In London dinner was given them by the Duke of Wellington at Apsley House. “This great house was presented to Wellington by the government for the single [sic] victory at Waterloo, along with wealth and a noble title which will descend throughout his line. As I sat there, I thought, ‘How would it have been if General Grant had been an Englishman—I wonder, I wonder?’ ”

So did Grant. Constantly. In fact, he became obsessed by the generosity of England to Marlborough and to Wellington and by the niggardliness of the United States to its unique savior. It is possible that Grant’s corruption in office stems from this resentment; certainly, he felt that he had every right to take expensive presents from men who gained thereby favors. Until ruined by a speculator-friend of his son, Grant seems to have acquired a fortune; although nowhere near as large as that of the master-criminal Lyndon Johnson, it was probably larger than that of another receiver of rich men’s gifts, General Eisenhower.

Circling the globe, the vigorous Grant enjoyed sight-seeing and Julia enjoyed shopping. There was culture, too: at Heidelberg “we remained there all night and listened with pleasure to Wagner or Liszt—I cannot remember which—who performed several of his own delightful pieces of music for us.” (It was Wagner.) “Of course, we visited the Taj and admired it as everyone does…. Everyone says it is the most beautiful building in the world, and I suppose it is. Only I think that everyone has not seen the Capitol at Washington!” It is no accident that General Grant’s favorite book was Innocents Abroad. After nearly two years, Maggie and Jiggs completed the grand tour, and came home with every hope of returning to the “dear old house” in Washington.

A triumphal progress across the States began on the West Coast (it was Grant’s misfortune never to have become what he had wanted to be ever since his early years in the army, a Californian). Then they returned to their last official home, Galena, Illinois, “To Galena, dear Galena, where we were at home again in reality,” writes Julia. Then “after a week’s rest, we went to Chicago.” The Grants were effete Easterners now, and Galena was no more than a place from which to regain the heights. “We were at Galena when the Republican Convention met at Chicago…. I did not feel that General Grant would be nominated…. The General would not believe me, but I saw it plainly.” Julia was right, and James A. Garfield was nominated and elected.

Galena was promptly abandoned for a handsome house in New York City’s East Sixty-sixth Street. The Grants’ days were halcyon until that grim moment when Grant cried out while eating a peach: he thought that something had stung him in the throat. It was cancer. The Grants were broke, and now the General was dying. Happily, various magnates like the Drexels and the Vanderbilts were willing to help out. But Grant was too proud for overt charity. Instead he accepted Mark Twain’s offer to write his memoirs. And so, “General Grant, commander-in-chief of 1,000,000 men, General Grant, eight years President of the United States, was writing, writing of his own grand deeds, recording them that he might leave a home and independence to his family.” On July 19, 1885, Grant finished the book, “and on the morning of July the twenty-third, he, my beloved, my all, passed away, and I was alone, alone.”

In Patriotic Gore Edmund Wilson writes: “It was the age of the audacious confidence man, and Grant was the incurable sucker. He easily fell victim to their [sic] trickery and allowed them to betray him into compromising his office because he could not believe that such people existed.” This strikes me as all wrong. I think Grant knew exactly what was going on. For instance, when Grant’s private secretary General Babcock was indicted for his part in the Whisky Ring, the President, with Nixonian zeal, gave a false deposition attesting to Babcock’s character. Then Grant saw to it that the witnesses for the prosecution would not, as originally agreed, be granted exemption for testifying. When this did not inhibit the United States Attorney handling the suit, Grant fired him in mid-case: obstruction of justice in spades.

More to the point, it is simply not possible to read Grant’s memoirs without realizing that the author is a man of first-rate intelligence. As president, he made it his policy to be cryptic and taciturn, partly in order not to be bored by the politicians (and from the preening Charles Sumner to the atrocious Roscoe Conkling it was an age of insufferable megalomaniacs, so nicely described by Henry Adams in Democracy) and partly not to give the game away. After all, everyone was on the take. Since an ungrateful nation had neglected to give him a Blenheim palace, Grant felt perfectly justified in consorting with such crooks as Jim Fisk and Jay Gould, and profiting from their crimes.

Neither in war nor in peace did Grant respect the “horrid old Constitution.” This disrespect led to such bizarre shenanigans as Babcock’s deal to buy and annex to the United States the unhappy island of Santo Domingo, the Treasury’s money to be divvied up between Babcock and the Dominican president (and, perhaps, Grant, too). Fortunately, Grant was saved from this folly by Cabinet and Congress. Later, in his memoirs, he loftily justifies the caper by saying that Santo Domingo would have been a nice place to put the former slaves.

Between Lincoln and Grant the original American republic of states united in free association was jettisoned. From the many states they forged one union, a centralized nation-state devoted to the acquisition of wealth and territory by any means. Piously, they spoke of the need to eliminate slavery but, as Grant remarked to Prince Bismarck, the real struggle “in the beginning” was to preserve the Union, and slavery was a secondary issue. It is no accident that although Lincoln was swift to go to war for the Union, he was downright lackadaisical when it came to Emancipation. Much of the sympathy for the South among enlightened Europeans of that day was due to the fierce arbitrariness of Lincoln’s policy to deny the states their constitutional rights while refusing to take a firm stand on the moral issue of slavery until the war was half done.

In the last thirty-four years, the republic has become, in many ways, the sort of armed camp that Grant so much esteemed in the South. For both Lincoln and Grant it was e pluribus unum no matter what the price in blood or constitutional rights. Now those centrifugal forces they helped to release a century ago are running down and a countervailing force is being felt: ex uno plures.

But enough. In this bicentennial year, let us only praise famous men, as the benign spirit of Walt Disney ranges up and down the land. Let us look only to what was good in Ulysses S. Grant. Let us forget the corrupted little president and remember only the great general, the kind and exquisitely tactful leader, the Roman figure who, when dying, did his duty and made the last years of his beloved goose of a wife comfortable and happy.

This Issue

September 18, 1975