At midnight on September 30, 1966, they let Albert Speer out of Spandau. The double gates of the fortress opened, headlights blazed, and two black cars came accelerating down the drive toward us. An explosion of lights from the press; a glimpse of the astonished, tremulously smiling old faces of Schirach and Speer. The Berliners around me, massed in the darkness up a grassy bank, clapped a little but raised no cheer. I was aware of their emotion as we waited in silence, and thought at first that it was political: if not explicitly pro-Nazi, then at least nationalist. But when they clapped and murmured, I understood. Speer was a “Heimkehrer” to them, the personification of the tens of thousands who had trickled home from foreign captivity over the years and of those who would never return. He was home again, one more member of the German family limping back out of the night.

During the twenty years of his imprisonment, Speer kept up a clandestine diary, written mostly on toilet paper. It was more than just a journal. Months of apathetic misery might pass without an entry; then came busy pages of self-analysis, a work on the history of the window, notes on nature or gardening. Almost from the start, he was able to find jailers and visitors willing to take the risk of smuggling the material out, with his own private letters, and to bring family and even business letters back past the censorship. On his release, some 25,000 scribbled pages were waiting for him. “I shied away from looking at that mass of papers which is all that has remained of my life between my fortieth and my sixtieth years.” A decade later, he composed himself, sat down to the notes and began to edit them.

The unique quality of the diaries is that they are without hope. The prison memoirs of Silvio Pellico, the Carbonarist, are full of lively contempt for the system which held him captive, of confidence in liberation, rescue, or escape. Gramsci’s prison letters come from a great spirit certain that his cause will triumph, still working for it from his cell. Speer, who had been Hitler’s young court architect and stage manager, then—as he puts it—his Carnot who organized the colossal production drive of the later war years, considered himself guilty. He recognized his mistake and his crime, and never fantasized about some mighty bar of history which would justify his actions. In all these pages there is no mention, not even a dream, of escape from Spandau. Robbed of all those mental resources which can keep a political prisoner going, Speer had to treat his twenty years as pure penance. Only once does he break down and rail, as the last year of his sentence begins.

At the Nuremburg trial, high moral and humanitarian principles were voiced. I was sentenced in accordance with them, and I inwardly accepted those principles; I even made myself their advocate to my fellow prisoners…. But I did so without knowing the limits of my own strength. Today I know that I long ago used it up. I am an old man…. I have been deformed. Granted, my judges sentenced me to only twenty years imprisonment to make it plain that I did not deserve a life sentence. But in reality they have physically and mentally destroyed me. Ah, these spokesmen of humanitarianism!… It has really been life. Now irrecoverable. And liberty will restore nothing to me.

The diaries, it must be said, tail off. As he grows older and more settled into the monastic routine of Spandau—his tireless gardening, his exercise walks which became an imaginary march, worked out kilometer by kilometer, across Asia and down the American continent—there is less reflection on the Third Reich, and he wearies of investigating his own conscience: “No human being can go on asserting his guilt for so many years and remain sincere.” But three themes dominate the papers. The first is the chronicle of existence at Spandau, the endless monthly rotation of the Four Powers changing guard over one corridor of an empty penitentiary, over seven prisoners who became three and now are one—Rudolf Hess. The other two themes are questions. What man or creature was Adolf Hitler? What man or creature was I, that I could serve him and know him so closely and never—until the final months—see that he was evil?

Speer, it turns out, was more profoundly a fascist than we knew—or than he knows. It is true that he never led a march on Rome, screamed about geopolitical determinism from a platform, or took notice of racist theory and practice. But the reader of these diaries will find, much more plainly than he will find it in the author’s previous memoirs, Inside the Third Reich, that the idea of Albert Speer as the unpolitical technocrat who simply followed his specialty and ignored wider responsibilities is not adequate. He was the essential Janus figure of twentieth-century fascism, one face staring back into the glories and certainties of the past, the other—its eyes half-closed—turned forward as the legs stride rapidly ahead into an industrialized future. Beware of the architect who builds Greek temples and Venetian palazzi out of ferro-concrete!

Advertisement

Speer was a “poetic” young man. He recoiled from the urban, technical world he found about him. He was shocked by Gropius and Miës van der Rohe, who accepted the twentieth century and made an architecture intended to express and be useful to the century. As a student, Speer would sit in the Romanisches Café in Berlin and stare in wonder at Grosz and Käthe Kollwitz, Dix and Pechstein. But “when I look at the newspapers now and see the triumph of all the art that is after all the art of my generation, I realize in hindsight how little I was a contemporary of those others…. Everything I did turned romantic in my hands, and a revolution in art passed me by without leaving a trace on my work.”

He was rebellious and yet conservative. He despised the authoritarian society of the Empire which survived into the Weimar Republic, and yet enjoyed without question the caste system of National Socialism. He was passionately excited by new technical possibilities in construction and lighting, but hated the culture of cities, the “Asphaltzivilisation.” And so Hitler got him, with no more trouble than he got millions of others.

My distaste for big cities, for the type of person they produced…all this was part and parcel of the romantic protest against civilisation. I regarded Hitler above all as the preserver of the world of the nineteenth century against that disturbing metropolitan world which I feared lay in the future of all of us. Viewed in that light, I might actually have been waiting for Hitler.

German fascism ate the past and excreted the future. Speer joined Hitler dreaming of building solid little homesteads for craftsmen, and found himself designing buildings for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, monstrous projects with modern proportions and vulgar classical detail. The regime which promised to restore a rural past violently accelerated the urbanization and industrialization of Germany. Speer became minister of armaments. “Architecture I loved, and hoped to make my name live on in history by building. But my real work consisted in the organization of an enormous system of technology. Since then, my life has remained attached to a cause that I at bottom disliked.”

It was so like Speer that his disillusion with Hitler in the last months of the war should have been an aesthetic perception. How, he asks himself in 1946, could he have failed to notice that Hitler had a second face? “I suddenly discovered how ugly, how repellent and ill proportioned, Hitler’s face was.”

Of the man behind the two countenances, he becomes less sure as the prison years pass. “I am completely uncertain when and where he was really himself, his image not distorted by playacting, tactical considerations, joy in lying. I could not even say what his feeling toward me actually was…. I don’t even know what he felt for Germany. Did he love this country even a little, or was it only an instrument for his plans?” But for all Speer’s unsureness, the fragments of recollection in his diaries bring us as close to Hitler as we are likely to get. Imperious know-all, touchy autodidact, he comes out even more obviously as the supreme product of the “Age of Will,” when men without qualifications studied handbooks on how to expand their will power like a muscle, to impose themselves by mesmerism, after-dinner speaking, or perfect tea-party manners. Speer actually discovered that Hitler used a chest-expander, in order to keep his raised arm rigid at long parades.

The more we know, the more it appears that Charlie Chaplin got Hitler as right as anyone. Here we have him designing a fifteen-hundred-ton tank, or stunning his courtiers by producing crayon stage sketches for every scene in the Ring, or “studying” long abstruse works by furtively reading the last pages, or presenting Nietzsche’s sister with a bouquet so enormous that she couldn’t hold it. Speer produces a wonderful Great Dictator set-piece about Hitler’s visit to Augsburg, teaching the city fathers their own local history, rushing about the municipal theater instructing the staff on the minutiae and the professional knacks of stage machinery, barking instructions about the height of the new town hall at the paralyzed Gauleiter, lecturing his entourage—through mouthfuls of strudel in the best Augsburg hotel—on medieval town planning. Looking back, Speer concluded that Hitler had only two real passions: theatrical production and architecture (a single subject to him), and the conquest and resettlement of Russia. “Common to both subjects was his thinking in vast dimensions.”

Advertisement

Hatred was always a fuel. Speer saw quite early that “[Hitler’s] hatred was admiration that he refused to acknowledge.” When he told the Hitler Youth to be swift as greyhounds and hard as Krupp steel, his subconscious might have added “wise as German Jews, loyal as Russian Communists.” To silence this voice, he exterminated his rivals daily in his mind, as he did physically in the camps. Russian soldiers were “subhuman” because they fought to the death; German soldiers were heroes when they did the same.

The world and its peoples were the weedy smallholding he had inherited, the first of the family to read a book on scientific agriculture. There were fences to be knocked down, unprofitable bushes to be uprooted, a total reseeding to be carried through, and for everything else—vermin, torn-up rubbish, wild flowers, bad seedlings—the fire. Hitler talked compulsively of fire. Speer remembered him in raptures over films of burning Warsaw, breaking into a delirious prophecy of New York’s destruction by long-range jet bombers: “He described the skyscrapers being turned into gigantic burning torches, collapsing upon one another, the glow of the exploding city illuminating the dark sky….”

An old man shuffling around the prison path recalled these scenes. A spiral of smoke rose into the Berlin sky from his own garden fire, beside the tiny boulevards and stadiums of brick which he had laid out and planted with flowers over many years. A bough rustled: Grand Admiral Dönitz, the last Führer of the Third Reich, was stealing hazelnuts and stuffing them into his mouth. The guards yawned in their watchtowers, and shifted the slung rifles on their shoulders.

Ponderous and petty, the vegetable routine of Spandau crept on. Speer records it marvelously. It was—is—a place out of time. Here, four countries which have long followed divergent paths are still the victorious Allies of the war. Here, the four-power government of occupied Germany, which broke down nearly thirty years ago, is still in being. Each month, the guards of one nation relieve those of another and march up the drive with swinging arms, bringing their own commandant and their own cook. The monthly Prison Lunch, lavishly done in the directors’ quarters, used to be and no doubt remains one of the most sought-after invitations in the social life of the Berlin garrisons (officers only, of course). Especially in a French month. America is on guard in December, which assures the prisoners a good Christmas dinner. Russian months, like March, mean short commons. Forty times goulash, forty-eight times boiled potatoes, ten cabbage salads, fifty times bread, butter, and ersatz coffee (noted Speer in March 1964).

As usual, prisoners and warders gradually formed a defensive community against outside rules and inspections. All kinds of things found their way in and out of this supposedly vacuumsealed place: not only letters and notes, but cameras, transistor radios, and a quite large flow of booze. Much of Spandau’s quality is summed up in the regulation which permitted prisoners to keep “official” notes and then committed them to the prison shredder at regular intervals.

Grave crises sometimes arose. In November 1950, a ball of horse manure wrapped in paper was found in Schirach’s bed. The object was placed in a locked empty cell under a spotlight, until the Soviet, American, French, and British prison directors could make separate visits to inspect it with their advisers. This mystery, which racked the Four Power administration, was never solved. Then, in August 1960, a period of international tension was ushered in by the decision of the Russian woman censor that the prisoners should not be allowed to listen to Don Giovanni in the course of their monthly three hours of gramophone music (“that’s an opera about love, and everything that has to do with love is not permitted the prisoners”). After many hours of argument, the directors agreed that no operas at all would be permitted in future: they had studied some of their plots, and felt that they would make the prisoners “restless.”

Neurath was released in 1954; Raeder, Dönitz, and Funk in each succeeding year. Albert Speer and Baldur von Schirach remained to the end of their sentences in 1966. Now there is only Rudolf Hess. As everyone knows, it is the Soviet side that insists on retaining him to the end of his life, and that refused to shorten the sentences of Speer and Schirach. The three Western powers would have gladly wound up Spandau and turned its inmates loose many years ago. But it is not merely the political point, the importance of holding on at Spandau as a form of power-sharing within West Berlin, that motivates the Russians. The glory of 1945, the final fanfare of the Great Patriotic War have not quite died out while Hess survives, while Russian soldiers hear him groan in his sleep or watch him flitting down the path in the shade of trees which Speer planted. The Russians have the right to guard their war memorial in the Tiergarten, in the British sector. Spandau is another war memorial, but one whose sacred flame—one man’s life—will soon go out.

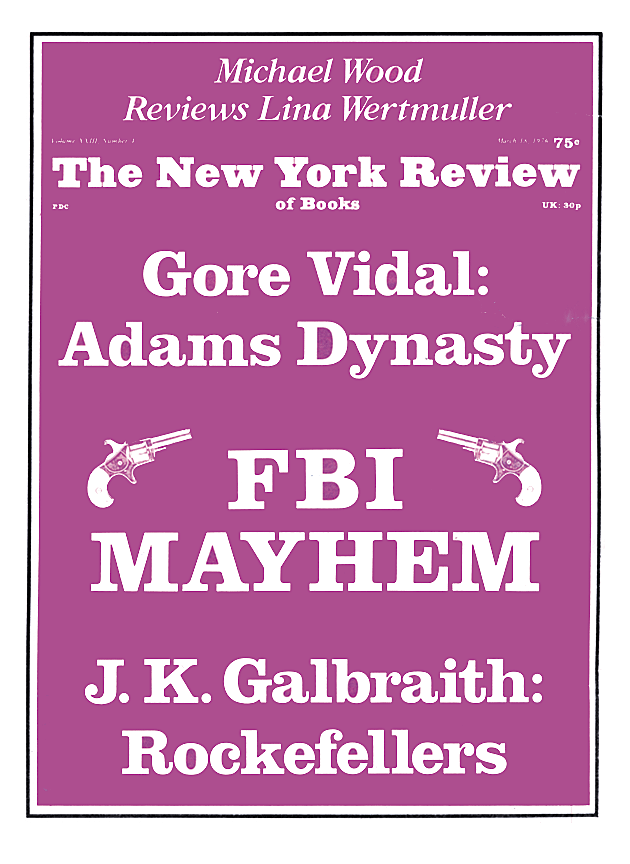

This Issue

March 18, 1976