To the Editors:

Here is one more letter for you to read on behalf of a man whose life is threatened by a familiar abbreviation: KGB. Unlike gods, evil likes to be abbreviated, for in this way it acquires a certain domesticated air, something like one’s initials, and thus gets an almost legitimate right to exist. In a peculiar way, abbreviations of evil reduce our willingness to fight it, and we even can mistake it for an airline or TV company. Anyway, it simplifies our notion of the phenomenon.

KGB means in Russian a committee of State Security, and, because the English letters in any case do not coincide with the Russian ones, I suggest that you interpret these initials merely as firing squad, labor camp, or mental hospital, and one of those things is in store for Tomas Venclova, in whose behalf this letter is written.

Tomas Venclova is a Lithuanian, which makes things worse, because very few Americans have any idea where Lithuania is. Sparing you a geography and history lesson, let me state that Mr. Venclova is the best poet living on the territory of that empire of which Lithuania is a small province. I dare to state this evaluation of his work because I am acquainted with it perhaps more than anyone else in this hemisphere, since I have translated his poetry into Russian. In addition to Russian, his works have been translated into Polish, German, and French. He is also very well known among European linguists for his semiotic studies, and last year he was invited to teach a course at Berkeley for a year, but was refused an exit visa.

Mr. Venclova is himself the first person to translate into Lithuanian the works of T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden, Robert Frost, W. B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, and others. He has also translated the English metaphysical poets. The wide range of these names shouldn’t embarrass you, for in the literatures of small nations it is a common thing for one man to do all the jobs. Besides, translation has been Venclova’s main source of income for years.

On May 11, 1975, Venclova applied to the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Communist Party for permission to leave the country. Since then nothing has been heard about him, and in the light of events described in available documents one fears for his future.* I urge all of you who read this letter to do everything in your power to help Mr. Venclova obtain permission to leave the USSR. Your letters and cables should be sent to: 1) Anatoly Dobrynin, Ambassador, Embassy of the USSR, Washington, DC; 2)The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Lithuania, Vilnius, USSR; 3) The Union of Writers, Lithuania, Vilnius, USSR; 4) Mr. Charles Runyon, Legal Advisor for Humanitarian Affairs, The Department of State, Washington, DC, 20520; and 5) your congressmen.

Unfortunately, a human being is able to comprehend only that amount of evil which he is able to commit himself. This is precisely what puts all those abbreviated agencies in a superior position and makes it difficult for us to fight them. The Soviet Union is a country where the problem of crime has been solved by the state—it is performed by government employees, and they are professionals. Therefore I would like to take this opportunity to suggest to all people in this country who are concerned with civil liberties in the East to create, under the auspices of the Congress or the Department of State, a separate body which would concern itself with problems of this kind. In addition, all information on arrests, tortures, and murders should be fed into computers and matched with the names of persons and organizations which could take action or publicize such matters. The need for centralization of our efforts in this area is due to the fact that we are dealing with professionals sponsored by the state, and we cannot afford to be scattered and amateurish. Amnesty International, for all its good works, is not enough—it is too late to defend from the outside a person already inside a prison. We need to act efficiently and at much earlier stages. Any defense takes much longer than the prosecution, and time is not a good thing any more when it is at the disposal of the state.

Joseph Brodsky

Poet in Residence

University of Michigan

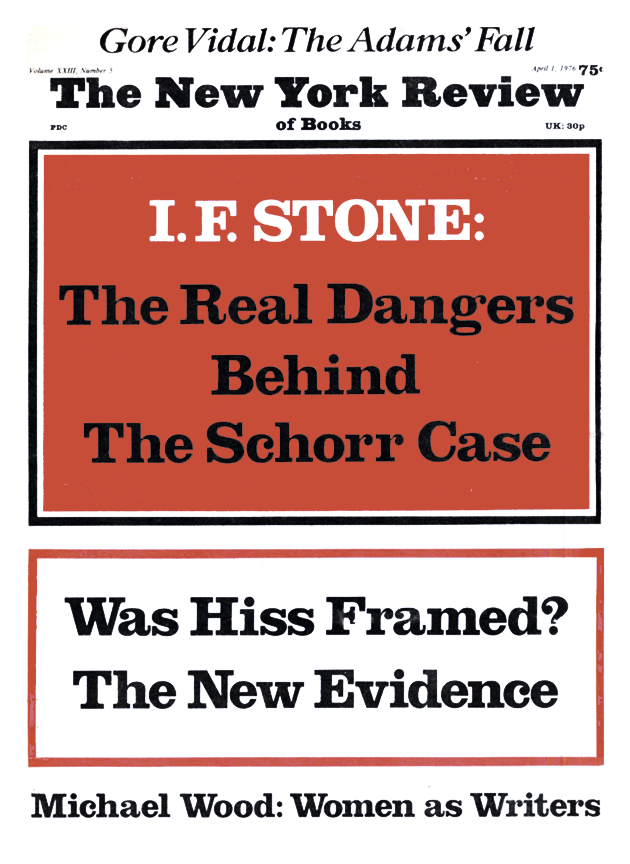

This Issue

April 1, 1976

-

*

An underground appeal to Western European intellectuals was published in a recent issue (No. 20) of the samizdat journal, The Chronicle of the Lithuanian Catholic Church. It states that three Lithuanian dissident intellectuals, Mindaugas Tamonis, Arunas Tarabilda, and J. Kazlauskas, have died within the past several years under mysterious circumstances, and blames the KGB for the deaths. The Chronicle‘s editors fear that a similar fate may be in store for Tomas Venclova, who has asked to be allowed to emigrate. ↩