“Once I thought,” Ellen Moers writes in her preface, “that segregating major writers from the general course of literary history simply because of their sex was insulting.” I confess I thought so too before I read her book, and even now I’m not convinced we were entirely wrong. The segregation of women writers from men, however it is done, must, in the present state of the game, carry a large streak of condescension. Moers says she used to find Elizabeth Gaskell and Anne Brontë boring, while she could “barely read” Mary Shelley and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. But “reading them anew as women writers” taught her how to “get excited” about them. She means to say that the fact that these writers were women is important, and of course she is right. But she is on the edge of saying they are not bad writers considering they are women, and her whole book hovers on just this edge.

Mme de Genlis, Ann Radcliffe, George Sand are no doubt “major women writers,” as Moers says. But Mme de Lafayette, Jane Austen, Emily Brontë, and George Eliot are major writers without any kind of qualification, and “major women writers” begins to look like a protected constituency to which it would be an honor not to belong. It is this sense of a rather cozy club that accounts, I think, for the mild claustrophobia one feels on finishing Ellen Moers’s highly intelligent and thoroughly well-informed book. In its shakier moments, Literary Women is a cheerful, printed, upside-down version of one of those dreary male societies and institutions that have so doggedly excluded women. Ellen Moers herself speaks of her “saturated reading of women’s literature,” and perhaps I’m simply saying that the saturation shows.

Another difficulty, of course, is the broadness of Moers’s central critical category: women, more than half the species. “There is no single female tradition in literature,” Moers insists. “There is no single female style in literature.” But I’m not sure that beyond certain biological specifications and a depressing common history of subjection there is even a single female creature we can call a woman. Twice Moers talks of women writers as separated by “everything but sex,” but just what sort of connection remains then for a writer? Virginia Woolf, in A Room of One’s Own, makes a funny and pointed slip:

Moreover, I thought, looking at the four famous names, what had George Eliot in common with Emily Brontë? Did not Charlotte Brontë fail entirely to understand Jane Austen? Save for the possibly relevant fact that not one of them had a child, four more incongruous characters could not have met together in a room—so much so that it is tempting to invent a meeting and a dialogue between them.

Woolf has forgotten that Charlotte and Emily Brontë were sisters, and spoke uninvented dialogue to each other for most of their lives, but of course she is right about the literary incongruity between them. Wuthering Heights and Villette seem to stem from different universes, not from the opposite ends of a cold parsonage, and if the fact that the two writers were sisters won’t tie them together for literary purposes, it seems unlikely that the fact that they were both women will do the trick.

Even so, in spite of my claustrophobia and my doubts about the dimensions of Moers’s enterprise, I am persuaded by a large part of her argument. It seems clear that women writers do read other women in a way that they don’t read men, and that, as Moers says, “there appears to be a rule that wherever literary women achieve real distinction with an apparently new departure, there is a female literary model of less distinction in their past.” (“It is useless to go to the great men writers for help,” Woolf wrote, “however much one may go to them for pleasure. Lamb, Browne, Thackeray, Newman, Sterne, Dickens, De Quincey—whoever it may be—never helped a women yet, though she may have learnt a few tricks of them and adapted them to her use.”) Thus Mrs. Gaskell owes a debt to Mrs. Trollope and Mrs. Tonna; Jane Austen learns from Maria Edgeworth and Fanny Burney and Mary Brunton; Emily Dickinson devours Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

The tradition here doesn’t really concern style or even content so much as confidence. Women are seen writing in a particular mode and become images of possibility for other women. The ground is broken. Moers remarks that “it is right for every woman writer of original creative talent to be outraged at the very thought that the ground needs to be broken especially for her, just because she is a woman,” but the fact is there, and fully justifies Moers’s careful attention to ground-breaking writers like George Sand—Matthew Arnold spoke of “the immense vibration of George Sand’s voice upon the ear of Europe”—and Mme de Staël. Moers’s chapter on de Staël’s Corinne and her operatic descendants, all the way down the century to George Eliot’s Gwendolen, in Daniel Deronda, is perhaps the best thing in the book, displays a fine blend of scholarship, critical good sense, and easy humor:

Advertisement

George Eliot directs our attention to a source of the performing fantasies in women’s literature more durable and more dangerous even than societal restrictions on women’s careers. That is, the admiration on which little girls are fed, in treacly spoonfuls, from their earliest years. Little boys, who also come in for their share, are made to outgrow the poisonous food; but throughout female youth, often to the brink of marriage, girls are praised for cuteness, for looks, for dress, for chatter, for recitations, for jangling rhymes, for crude sketches, for bad acting, for wretched dancing and out-of-tune singing…. Some time in the future, television may prove to be an invention as liberating for women as was the typewriter, by providing, not jobs, but something to look at in the home other than little girls….

Ellen Moers’s tone, when she is writing well, is offhand and very engaging (“Take someone like Mary Wollstonecraft, if there ever was anyone else like Mary Wollstonecraft”). When she is not writing so well it turns to gush (“George Sand and Elizabeth Barrett Browning; what positively miraculous beings they were”).

Moers identifies several topics and stances that do seem genuinely to belong to women: mothers (cropping up again and again in the work of Colette and Woolf); motherhood (brilliantly illustrated in the queasy ambivalences of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein); a desire to master in fiction precisely those zones of mundane or exotic reality from which women were excluded in fact (Harriet Martineau’s and Charlotte Brontë’s intense interest in the “real, cool, and solid”; Ann Radcliffe’s and George Sand’s emphasis on travel and adventure). On the other hand, I don’t really believe that an interest in money is “an essentially female phenomenon”; or that illiteracy is “plainly a woman’s theme”; or that “nothing separates female experience from male experience more sharply, and more early in life, than the compulsion to visualize the self.” These notions seem to topple back into the very mythology that one had hoped the women’s movement might help to scotch: women are practical and parsimonious, do-gooders, and vain. But the chief problem, perhaps, lies in the level of Moers’s inquiry. She is looking mainly for female themes and compulsions where she needs, I think, female angles of vision and manners of relating to what for men is the real world.

There are a couple of lines in Literary Women which open up a range of possibilities in this respect. Moers describes the “spray of hostile negatives” in the first paragraphs of Jane Eyre (“There was no possibility of taking a walk that day … out of the question…. I never liked long walks…”), and adds, “Before she gives Jane Eyre a name, or a class, or an age, Brontë makes her speaker both a person and a female in the quickest shorthand available to women writers: she has her say no.” Saying no links Jane Eyre to Harriet Beecher Stowe and the world of Uncle Tom’s Cabin far more seriously than Brontë’s recurring metaphors of slavery and her talk of a heart in insurrection. It connects both Brontë and Stowe to George Sand in her firm and amiable argument with Balzac. In answer to his grand and gloomy comédie humaine, George Sand wanted to write l’éclogue humaine, le poème, le roman humain:

You want to, and know how to portray man just as he is, before your eyes—so be it! But I feel called upon to portray him as I wish him to become, as I think he should be.

And in their no-saying we can even, I think, put Charlotte and Emily Brontë together after all. The drastic rejection of adult social life in Wuthering Heights answers the passionate refusal of female nonentity running through all Charlotte Brontë’s writings.

Virginia Woolf suggested that “the whole structure … of the early nineteenth-century novel was raised, if one was a woman, by a mind which was slightly pulled from the straight, and made to alter its clear vision in deference to external authority.” But she was pursuing a peculiarly quietist political line in A Room of One’s Own, and we may find the pure, prior straightness and clear vision of her quotation to be wishful and suspect, lost paradises that have never been found.

Advertisement

Surely the mind pulled from the straight by women’s position in society, by their isolation from the world of war and politics and business and law, is especially equipped to respond to that world radically: that is its clear vision. It is just this sort of displacement and dislocation that lends such power to George Eliot’s perception of tragedy in the mere repetition of ordinary sadness, in the “very fact of frequency.” When Henry James, in The Portrait of a Lady, accompanies Isabel Archer into her “house of darkness,” he speaks for everyone, male and female, who has trapped himself inside an irretrievable error. When George Eliot, in Middlemarch, finds Dorothea Brooke sobbing bitterly on her honeymoon, she speaks for everyone, male and female, who has discovered the misery of everyday life, but this is a subject on which women can speak with exceptional eloquence and competence.

Virginia Woolf suggested (playfully, I hope) that one could recognize the sex of sentences, and that Charlotte Brontë, trying to handle a man’s sentence, “stumbled and fell,” while George Eliot “committed atrocities with it that beggar description.” There is an element of self-defense here, no doubt, since Woolf wrote sentences that were all too often coyly female, fluttering off into present participles like a girl going into a giggle. But the remark contains a real clue to the way women write, a pointer to some sort of generalization. They write men’s sentences, undermined by women’s resistance.

Jane Austen, for example, did not write the “natural, shapely sentence” that Woolf attributes to her, if by that we understand a neat modest prose that looks like a well-turned ankle. Nor is it really true to say, as Ellen Moers does, that Austen “studied Maria Edgeworth more attentively than Scott, and Fanny Burney more than Richardson.” The famous opening sàlvo of Pride and Prejudice—“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife”—is not only a man’s sentence, it is Henry Fielding’s sentence, irony and all. What makes it specifically Jane Austen’s, and perhaps specifically female, is not its movement or its syntax, but the quality of the reservations it manages to crowd into its brief span, the way it manages to say no while seeming to say yes. Truth, universally, acknowledged, good, must, want—all those words are subject to doubts, retractions, and generous possibilities of interpretation.

Fielding, I think, could have managed a remark along these lines, but he would have been more openly distressed, and he would have expected something to be done about this oppressive state of affairs. Austen speaks of a money-grubbing world not as a man who has some funds or might inherit some, but as a woman imprisoned so deep in that world that she can only laugh at the general helplessness and indignity of her sex. One of the great distinctions of Austen’s work is not her insistent concern with money, which so irritated Emerson (“Suicide is more respectable,” he said), and which Moers thinks has been insufficiently noticed by critics, but the way in which money is so profoundly interwoven into her characters’ lives, so that almost everyone, literally, has a price:

About thirty years ago, Miss Maria Ward of Huntingdon, with only seven thousand pounds, had the good luck to captivate Sir Thomas Bertram, of Mansfield Park, in the county of Northampton, and to be thereby raised to the rank of a baronet’s lady, with all the comforts and consequences of an handsome house and large income. All Huntingdon exclaimed on the greatness of the match, and her uncle, the lawyer, himself, allowed her to be at least three thousand pounds short of any equitable claim to it.

All Huntingdon, the implied quotation from the lawyer uncle, the careful malice in the words good luck and captivate and especially thereby, the surreptitious irony of only and at least being attached to fairly large sums of money, the whole passage suggests a community seen from inside, even from its underside. And the final point, of course, is not the money, but the eager snobbery and pervading complicity that Austen is displaying for us. Women in Austen are helpless, marriage is their only way out, a good marriage is their only way of making a good life. All this is true, but captivating a baronet goes well beyond the call of need, and the possession of a good fortune in no way guarantees a good marriage. Austen sees her whole world, men and women, as caught up in a circle of subtle blackmail.

I am making her sound too sinister. The undertones are there, but they are undertones. However, they do have a great deal to do with the quality of Austen’s prose, which I would describe, in Virginia Woolf’s terms, as composed of a man’s sentences delivered with a woman’s accent. That I find myself engaged in such blatant discrimination is a tribute to Moers’s book and the challenges it represents. It is insulting, I still believe, to segregate writers by sex; but it is merely stupid to pretend that being a woman is no different from being a man.

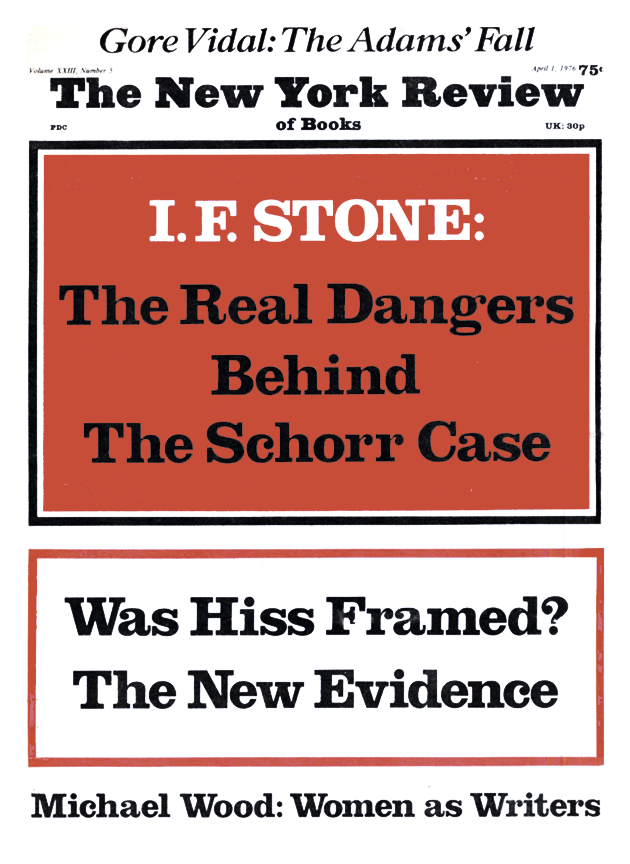

This Issue

April 1, 1976