Perhaps the most shocking example of the FBI’s abuse of power was its campaign of unrelenting surveillance and harassment of Martin Luther King, Jr. Hoover set out to destroy King by using the full powers of the FBI against him. Various theories have been offered for Hoover’s motive, and a combination of circumstances may have been involved. Hoover was enraged when King criticized the FBI. The FBI’s stated rationale for bugging and tapping King was to uncover “Communist” influence on the civil rights leader. Nor was Hoover pleased with King’s growing success in the use of nonviolent confrontation. The police dogs of Birmingham snarling and ripping at black men and women in the summer of 1963 created a bad image for law enforcement. “We Shall Overcome” fell harshly on Hoover’s ears.

William Sullivan, the assistant director of the FBI under Hoover, said that Hoover’s view of blacks was the root cause of the campaign against King. “The real reason was that Hoover disliked blacks,” Sullivan told me. “He disliked Negroes. All you have to do is see how many he hired before Bobby came in. None. He told me himself he would never have one so long as he was FBI Director.1 He disliked the civil rights movement. You had a black of national prominence heading the movement. He gave Hoover a peg by criticizing the FBI. And King upset Hoover’s nice cozy relationship with Southern sheriffs and police. They helped us on bank robberies and such, and they kept the black man in his place. Hoover didn’t want anything to upset that relationship with law-enforcement authorities in the South.”

In the end, one is forced to conclude that the FBI sought to discredit King because J. Edgar Hoover was a racist. Hoover attacked King because King was black and powerful, and his power was growing. Who could foretell what might happen if the black people of America were to become mobilized behind such a leader? To Hoover, Martin Luther King was uppity and biggity, and he had to be stopped.

The FBI’s fear that King might become a black “messiah” was expressed in precisely these words in a memo from headquarters to field offices on March 4, 1968, one month before King’s death. The memo said one of the goals of the FBI’s counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO) against “Black Nationalist-Hate Groups” would be to prevent the rise of a “messiah” who could unify, and electrify, the militant black nationalist movement. Martin Luther King might “aspire to this position,” the memo added. “King could be a very real contender for this position should he abandon his supposed ‘obedience’ to ‘white, liberal doctrines’ (nonviolence) and embrace black nationalism.”

Just before King’s march on Washington in August 1963, Sullivan and Hoover began an exchange of memos about the degree of communist influence among blacks in the civil rights movement. Sullivan, who had earlier reported to Hoover that he saw no communist threat in King’s movement, soon told Hoover what he knew Hoover wanted to hear: “…we regard Martin Luther King to be the most dangerous and effective Negro leader in the country.”

The FBI had begun surveillance of King’s civil rights activities during the late Fifties. In January 1962 the FBI warned Attorney General Robert Kennedy that one of King’s senior advisers was a “member” of the Communist party, and later that year a formal FBI investigation was opened into alleged “Communist infiltration” of King’s movement. The FBI bombarded Robert Kennedy with memos warning of King’s continued contacts with the adviser and with a second associate who the FBI said had strong ties to the Communist party. In February 1963, after the FBI warned that King would be meeting with the two advisers, Kennedy wrote a note to Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall: “Burke—this is not getting any better.”

The FBI’s avowed concern over communist influence on King centered on the figure of Stanley Levison, a New York attorney long close to the civil rights leader. In his 1971 book Kennedy Justice, Victor Navasky reported that Robert Kennedy gave his approval to tap King after receiving FBI reports charging that Levison and Jack O’Dell, a member of the staff of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, had “Communist” backgrounds. By Navasky’s account, both President Kennedy and Robert Kennedy warned King about Levison and O’Dell in June 1963, and King then agreed to sever relations with the two men. O’Dell was eased out of the SCLC, Navasky wrote, but King after a time resumed his friendship with Levison. According to Navasky, who cites information from “Kennedyites,” this convinced Hoover that King was under communist control and led him to increase his pressure on Robert Kennedy to approve the wiretapping of King.

Advertisement

If a few communists or former communists had been associated with King, there would have been nothing illegal about it. But in fact, King and the SCLC had an explicit policy that no communist or communist sympathizer could serve on the staff of the SCLC. The FBI’s charges against King have never been substantiated.

In an interview with The Washington Post in December, 1975, Levison said: “I was never a member of the Communist Party. I did know some people who were…. Particularly in the 1930s and 1940s you scarcely could have been an intellectual in New York without knowing some.” Levison said he was a victim of “guilt by association.” The final report of the Church committee notes that two FBI reports “which summarize the FBI’s information about Adviser A”—Levison is not named—“do not contain evidence substantiating his purported relationship with the Communist Party.” The Church report also noted that on April 14, 1964, the FBI’s New York field office reported that King’s adviser “was not under the influence of the Communist Party.”

When O’Dell resigned from the SCLC in July of 1963, King accepted his resignation with a letter in which he said: “As you know we conducted what we felt to be a thorough inquiry into these charges and were unable to discover any present connections with the Communist Party on your part.” But King said he was accepting the resignation in order to avoid any public impression that the SCLC and the civil rights movement had any communist ties; the movement, King said, could not afford to risk “any such impressions.”

The FBI’s warnings that King had “Communist” advisers placed both President Kennedy and his brother in what they felt was a vulnerable political position. The administration was closely identified with King and had publicly defended him. The president did not want him tarred as a communist; on the other hand, if the administration failed to act, the FBI might leak the charges to the press, which could damage not only King but the Kennedys. They feared, in short, that Hoover would blackmail them.

According to Congressman Andrew Young, who had been an aide to King, after King met with the president in June 1963, the civil rights leader quoted Kennedy as saying “there was an attempt [by the FBI] to smear the movement on the basis of Communist influence.” By Young’s account, the president had also warned King: “I assume you know you’re under very close surveillance.”

The following month Hoover sent Robert Kennedy another memo charging that King was affiliated with communists. Courtney Evans, the FBI’s liaison man with the Justice Department, described Kennedy’s reaction: “The Attorney General stated that if this report got up to the Hill at this time, he would be impeached.”

One way to determine if Hoover’s charges about King were true, of course, was to tap his telephone. Evans testified that Robert Kennedy raised the question in a meeting with him in July of 1963. Evans had told Kennedy that King traveled a great deal and that he doubted that “surveillance of his home or office would be very productive.” Evans also suggested that if a tap on King ever became known, it could have unpleasant repercussions. “The AG said this did not concern him at all; that in view of the possible Communist influence in the racial situation, he thought it advisable to have as complete coverage as possible.” Evans advised Kennedy he would check into the possibility of a wiretap, but within a week, on July 25, Kennedy informed Evans that he had decided against tapping King.

But early in September, Sullivan recommended to Hoover that the FBI wiretap King. This was only a week after Sullivan had admitted to Hoover that he had been sadly mistaken in failing to preceive the communist threat in the racial movement. Hoover approved, although he scrawled he was still “dizzy over vacillation” about the degree of communist influence in the civil rights movement.

On October 7, Hoover formally requested Robert Kennedy’s approval of wiretaps on King’s home and office, citing “possible Communist influence in the racial situation.” On October 10, Evans and Kennedy took up the question of Hoover’s request. This time, according to the FBI memo of their meeting, Kennedy approved the taps on King “on a trial basis, and to continue it if productive results were forthcoming.” On October 21, Kennedy told the FBI that by a trial basis he meant thirty days, after which time the taps would have to be evaluated before any decision was made to continue them.

But the tap installed on King’s home in Atlanta remained in place for a year and six months, until April 1965.2 In addition to the tap on King’s home, the FBI wiretapped his hotel rooms in Los Angeles and Atlantic City, and SCLC headquarters in both Atlanta and New York. The longest tap, on the Atlanta office, lasted two years and eight months, from November, 1963, until June, 1966.

Advertisement

Three years later Hoover charged that the impetus to tap King had come from Robert Kennedy. By then Robert Kennedy had been assassinated. But his associates claimed that the pressure to tap King had come from Hoover, and that Kennedy had gone along with it to disprove FBI suspicions of King’s alleged communist ties. William Sullivan, who headed the FBI division that handled the wiretapping, supported the version of Kennedy’s friends when I talked to him. Asked whether the idea of tapping King came from the Attorney General or from Hoover, Sullivan told me, “Not from Bobby. It came from Hoover. He sent down a memo. He wanted King given the full treatment. The whole impetus came from us.” He added, “I do know that Bobby Kennedy resisted, resisted, and resisted tapping King. Finally we twisted the arm of the Attorney General to the point where he had to go. I guess he feared we would let that stuff go in the press if he said no. I know he resisted the electronic coverage. He didn’t want to put it on.”

In December 1963, after Sullivan had agreed that King was “the most dangerous and effective Negro leader in the country,” a meeting was convened at FBI headquarters in Washington to plan the FBI’s war on the civil rights leader. Among the tactics and subjects discussed was whether black FBI agents in the Atlanta area might be used, and how many would be needed, and whether TELSURS and MISURS (telephone and microphone surveillance) might be used against King’s associates. The agenda drawn up for the meeting asked:

What are the possibilities of using this [electronic surveillance]? Are there any disgruntled employees at SCLC and/or former employees who may be disgruntled, or disgruntled acquaintances? Does the office have any contacts among ministers, both colored and white, who are in a position to be of assistance, and if so, in what manner could we use them?

Do we have any information concerning any shady financial dealings of King which could be explored to our advantage? Was this point ever explored before? And what are the possibilities of placing a good looking female plant in King’s office?

There were twenty-one such ideas in the FBI agenda.

After this meeting the FBI began bugging King’s hotel and motel rooms, in addition to wiretapping his telephone conversations. The first bug was placed in the Willard Hotel, a block from the White House, when King stayed there in January 1964. In all, the FBI bugged sixteen of King’s hotel rooms in Washington and six states.3

Although Robert Kennedy approved the wiretaps, it is not clear that he ever knew of or approved the FBI’s use of bugs against King. When asked by the Church committee whether Kennedy had ever authorized the bugs or been told about them, Courtney Evans replied, “Not to my knowledge.”4 Kennedy received FBI memoranda based on the King bugs, but not so labeled; it is possible, however, that he guessed or suspected from reading the reports that the information in them came from hidden microphones.

On January 8, 1964, two days after the FBI began bugging King’s hotel rooms, Sullivan wrote a memo to Hoover. The time was approaching, he wrote, to take King “off his pedestal and reduce him completely in influence.” But if the FBI succeeded in that objective,

the Negroes will be left without a national leader of sufficiently compelling personality to steer them in the proper direction. This is what could happen, but need not happen if the right kind of a national Negro leader could at this time be gradually developed so as to overshadow Dr. King and be in the position to assume the role of the leadership of the Negro people when King has been completely discredited.

For some months I have been thinking about this matter. One day I had an opportunity to explore this from a philosophical and socio-logical standpoint with [name deleted] whom I have known for some years…. I asked him…if he knew any Negro of outstanding intelligence or ability…. [He] has submitted to me the name of the above-captioned person. Enclosed with this memorandum is an outline of [deleted] biography, it will be seen that [deleted] does have all the qualifications of the kind of a Negro I have in mind to advance to positions of national leadership.

I want to make it clear at once that I don’t propose that the FBI in any way become involved openly as the sponsor of a Negro leader to overshadow Martin Luther King. If this thing can be set up properly without the Bureau in any way becoming directly involved, I think it would be not only a great help to the FBI, but would be a fine thing for the country at large.

Hoover, pleased, replied, “I am glad to see that ‘light’ has finally, though dismally delayed, come to the Domestic Intelligence Division. I struggled for months to get over the fact that the Communists were taking over the racial movements, but our experts here couldn’t or wouldn’t see it. H.”

By the fall of 1964 the FBI’s campaign against King had become fullscale war. For months the Bureau had been bugging King’s hotel rooms, and now it began to whisper stories to reporters in Washington about alleged sexual activities of the civil rights leader. King, the FBI told reporters, had cavorted with women in his hotel rooms; explicit details were available to newsmen willing to listen to the FBI’s Decameron. The purpose of the FBI whispers was to publicize stories that King, whose power rested upon his moral authority, had a lively extra-marital sex life, which the FBI considered inconsistent with his public reputation and his profession as a minister. The FBI coupled these stories with its usual unsupported claims that King was under complete control of the Communist party.

Rumors circulated in Washington that the FBI had offered to let trusted reporters either see the transcripts of the bugging of King’s hotel rooms or listen to the actual tapes. In 1976 Benjamin Bradlee, the editor of The Washington Post, said that he had been offered a transcript of a King tape by Cartha D. (Deke) DeLoach, assistant director of the FBI, in the fall of 1964. At the time, Bradlee, was chief of Newsweek’s Washington bureau. “The circumstances involved a cover story we were doing on Hoover,” Bradlee told me. “I had finally succeeded in getting an interview with Hoover. It was to be me, Jay Iselin, and Dwight Martin from New York. On the morning of the interview we all had breakfast together to plan the interview, and then went back to the office around nine-thirty. The phone rings and it’s DeLoach. Martin is not acceptable to the Director. In an act I regret, we [Bradlee and Iselin] went over alone. We went in and saw Hoover and asked one question and he talked for thirty minutes.”

According to Bradlee, the interview was worthless. Afterward, Bradlee said, he met alone with DeLoach, who had promised to explain why Martin was barred.

He [DeLoach] showed me the file. He said Martin’s wife had been under some suspicion. It turned out to be his ex-wife, who was apparently an Oriental. During World War II she had seen a lot of military people. Since she worked for a Chinese tailor, it wasn’t surprising—her customers were military people.

[DeLoach] offered a transcript of Martin Luther King. No, I said, I did not want to see it.

It was made clear to Bradlee that the transcript was from the bugging of King’s hotel rooms. “I said I thought it was a tape. I know of a journalist in Atlanta who heard the tape.” But, Bradlee said, “it was a transcript he was offering, and I had the impression that he had the transcript on his desk next to the file on Dwight Martin’s ex-wife. He kind of hustled it—saying King made unpleasant references to the Kennedy family.” Asked whether the alleged remarks by King referred to Jacqueline Kennedy, Bradlee replied, “Yes.”5

According to Iselin, in the cab going back to the Newsweek office Bradlee told him that DeLoach’s conversation had been along the lines of “What do you think of a black man fooling around with white women?” Iselin told me: “Ben was offered the tapes. I remember my slack-jawed astonishment. We obviously declined to have anything to do with it.” Bradlee, Iselin recalls, said the tapes had been described to him as “based on the bugging of hotel rooms of King. They would get white girls in the rooms…that sort of thing.”

In October, Newsweek gave a large party to celebrate the opening of its new offices on the twelfth floor of an office building a block from the White House. Attorney General Katzenbach was there, and Iselin remembers needling Katzenbach and Burke Marshall, the assistant attorney general in charge of the Civil Rights Division. What kind of operation were they running, peddling smut, he asked them.

Katzenbach said that at the Newsweek offices Bradlee told him that the tapes he had been offered were “from hotel rooms and involved sexual activities…. Bradlee said DeLoach had offered interesting tapes, with a leer.”

Katzenbach described the incident to the Church committee, without revealing the names of Bradlee and Iselin. He testified that he had been dismayed “and felt that the President should be advised immediately.” He flew with Burke Marshall to the LBJ Ranch, where he told Johnson of his conversation with Bradlee, warning “that this was shocking conduct and politically extremely dangerous to the Presidency. I told the President my view that it should be stopped immediately and that he should personally contact Mr. Hoover.”

Katzenbach said he got the “impression” that Johnson would do so. The president, Katzenbach said in an interview, “sat in a rocker by the fire and pretty much listened. He didn’t comment one way or the other. But I had the distinct impression that he was going to do something about it to stop it.”6 Back in Washington on Monday, Katzenbach said, he was told by one or two other newspapermen of similar offers by the FBI.7 The same day, Katzenbach said, he confronted DeLoach. “He rather angrily denied it,” Katzenbach said. “I didn’t believe him.”

When I interviewed DeLoach, he disputed the accounts of Bradlee, Iselin, and Katzenbach. DeLoach said he had arranged an interview for Bradlee “with Mr. Hoover. The day before, Bradlee said he wanted to bring the man who would write the story. When he asked to bring the additional man, Mr. Hoover said have a file check. As a result of the file check, Mr. Hoover said he did not want to see the man.” DeLoach added, “At no point did I ever offer Bradlee the transcripts or to play the tape.” DeLoach also denied that Katzenbach had questioned him about making such an offer to Bradlee. “Absolutely not,” he said. “He did not ask about the transcripts.”

On November 18 Hoover met with a group of women reporters in Washington and pronounced King “the most notorious liar in the country.”8 Hoover specifically criticized King for telling his followers not to bother to report acts of violence to the FBI office in Albany, Georgia, because the agents were Southerners who would take no action on civil rights violations. Hoover claimed that “70 percent” of agents assigned to the South were born in the North.

Hoover’s astonishing attack on King received extensive coverage in the press and on television. In contrast, the prurient stories that the FBI had whispered to the press about King’s sex life were not achieving their purpose, for nobody would print them. Hoover apparently decided to take a more direct approach. On November 21, three days after Hoover’s remarks to the women journalists, the FBI mailed an anonymous letter and a tape of the King hotel room bugs to King and his wife Coretta.

The letter said:

King, there is only one thing left for you to do. You know what it is.

You have just 34 days in which to do it. This exact number has been selected for a specific reason. It has definite practical significance. You are done.9

The letter was mailed three weeks before King was due to receive the Nobel prize in Oslo, on December 10. Since it was accompanied by a tape which the FBI considered compromising, the letter could be interpreted as an invitation to King to kill himself. Apparently that is how King construed it, for Congressman Young told the Church committee that when King received the tape and the letter, “he felt somebody was trying to get him to commit suicide.”

William Sullivan told me that he had, on orders from Hoover, arranged to have a tape mailed to Mrs. King. He said he received the order from Hoover’s assistant, Alan H. Belmont.10

Belmont called me. We met at his request and he said Hoover and Tolson wanted certain tapes sent to Coretta King. I objected, not on moral grounds, but on practical grounds. I said, “She’ll know immediately that the FBI made the tapes.”

Belmont said King has been critical of Hoover and Hoover wants to stop that, and the tapes will blackmail him [King] into stopping. And Belmont said he was going to have the tapes sanitized so that Mrs. King will not know that they came from the FBI. He said, “I’ll arrange to have the tapes selected and I’ll have them sent to you in a box.”

In due course, Sullivan said, the box arrived, and he had the impression the tape it contained was “a composite of three tapes.”

Had the FBI put together a composite in order to select what it considered the most damaging parts of the various hotel room tapes to send to Mrs. King? “Probably,” Sullivan told me, “but I understood it was to sanitize, to disguise the FBI origin. Perhaps it was a composite of more than three tapes, I don’t know.” The work was done by the FBI laboratory, the same one proudly shown to the thousands of tourists who visit FBI headquarters each year in Washington. “I think Belmont called the lab,” Sullivan said. “I don’t know how it was done.

“Hoover called me on the phone and said he wanted it mailed from a Southern city. I picked an agent who was a very close-mouthed fellow; I picked him because I knew he wouldn’t talk about it. I never told him what was in the box. I told him what the assignment was. ‘Take this down to Tampa and mail it,’ and he did. He came back and told me it had been done. I never discussed it with Hoover afterward. He never mentioned it to me.”11

With the Hoover-King controversy now threatening to undermine King’s leadership and endanger the civil rights movement, other black leaders urged King to meet with the FBI director. King, the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, and other SCLC leaders met with Hoover and DeLoach in Hoover’s office on December 1. Precisely what was said is not clear. DeLoach has described it as “a very amicable meeting, a pleasant meeting between two great symbols of leadership.” Hoover, he said, told King that “in view of your stature and reputation and your leadership with the black community, you should do everything possible to be careful of your associates and be careful of your personal life, so that no question will be raised concerning your character at any time.”

This is supposed to have been said at a time when the FBI was bugging and wiretapping King’s hotel rooms—as King now knew, since he had received the tape—and leaking stories about King’s sex life to reporters. For the moment, Hoover’s blackmail techniques seemed to work. A subdued King said after the meeting that he and Hoover had reached “new levels of understanding.”

The tape, the apparent suicide letter, and the attempt to impugn King’s moral character were the most vicious aspects of the FBI’s campaign. But the FBI’s harassment of King reached as well into pettier matters. According to Frederick Schwarz, the Church committee’s counsel, the FBI in 1964 sought to block Marquette University from giving King an honorary degree “because it was thought unseemly,” since the university had once granted an honorary degree to Hoover. Later that year the FBI learned that King planned to visit Pope Paul VI. John Malone, the head of the FBI’s New York office, was dispatched to see Cardinal Spellman to persuade him to intervene with the Pope and prevent the audience. Malone thought he had succeeded, but the Pope met with King anyhow. “Astounding,” Hoover wrote on a memo. “I am amazed….”

Four years later King went to Memphis to participate in a strike of city garbage workers. The FBI campaign had not abated, for on March 28, 1968, the FBI drafted a blind memo—bearing no FBI markings—for distribution to “cooperative news media.” “The fine Hotel Lorraine in Memphis is owned and patronized exclusively by Negroes,” the memo said, “but King did not go there.” Instead, King was staying at “a plush Holiday Inn Motel, white-owned, operated, and almost exclusively white patronized.” The purpose of the proposed planted news item, the FBI documents said, was “to publicize hypocrisy on the part of Martin Luther King.” Hoover signed the FBI memo, “Okay, H.”

It was not established whether the memo was sent to the press, but King did change hotels. He went home to Atlanta, and when he returned to Memphis the following week, he moved into the Lorraine. Standing there on the balcony outside his room, he was shot and killed on April 4, 1968. James Earl Ray, a small-time escaped convict, pleaded guilty to the crime a year later and was sentenced to ninety-nine years in prison. But whether he acted alone or was part of a conspiracy remains an open question.

When the Church committee disclosed details of the FBI’s campaign against King, including the “suicide” letter, questions were publicly raised about whether the FBI’s actions against King could conceivably have extended to complicity in his murder. On November 26, 1975, Attorney General Edward H. Levi ordered a review of the FBI’s investigation into the death of Martin Luther King.

Conducted by J. Stanley Pottinger, head of the Justice Department’s civil rights division, the review found “no basis to believe that the FBI in any way caused the death of Dr. King,” or that the FBI’s investigation of his death had been less than thorough. But the study concluded that “the FBI undertook a systematic program of harassment of Dr. King in order to discredit him and harm both him and the movement he led.” Although Pottinger found no evidence of FBI complicity in King’s death, he said it was “possible” that a more detailed survey of the files would reach a different conclusion.

On April 29, Levi announced that an expanded investigation and a review of some 200,000 FBI documents on King would be conducted by a task force under Michael E. Shaheen, director of the department’s Office of Professional Responsibility. Levi said the new investigation would be asked to determine whether “the FBI was involved in the assassination of Dr. King” and whether the FBI’s actions against King require “criminal prosecutions.” A Justice Department spokesman said recently that the task force was expected to report “by January 1.”

On September 17 of this year, the House of Representatives voted to establish a select committee to investigate the murders of President Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., and empowered it to inquire into other assassinations as well. In its final report, the Church committee concluded: “The actions taken against Dr. King are indefensible. They represent a sad episode in the dark history of covert actions directed against law abiding citizens by a law enforcement agency.”

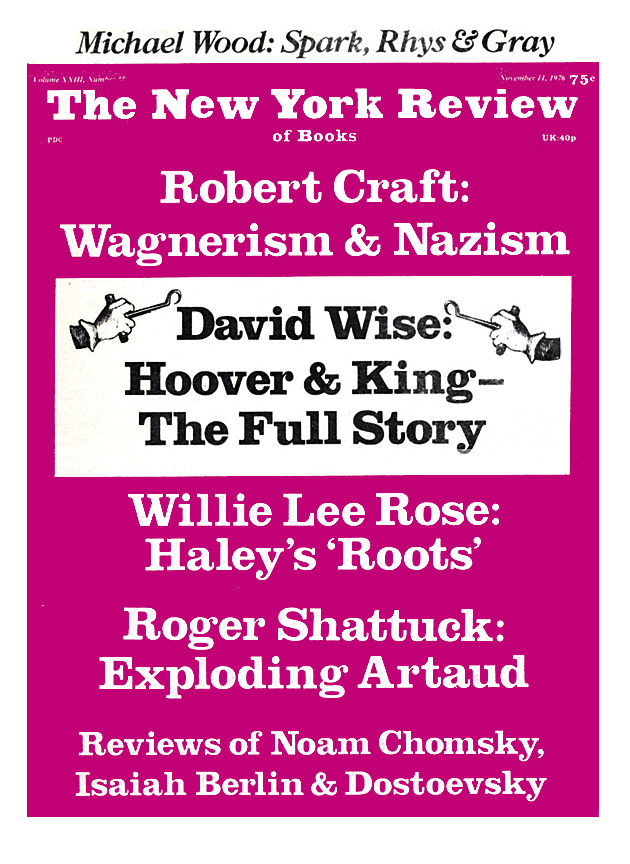

This Issue

November 11, 1976

-

1

After Robert Kennedy became attorney general, he asked Hoover how many black agents the FBI had, Sullivan testified to the Church committee. Hoover replied that the Bureau did not categorize people by race, creed, or color. That was laudatory, Kennedy said, but he still needed to know how many black agents there were in the FBI. Hoover had five black chauffeurs in the Bureau, Sullivan said, “so he automatically made them special agents.” In 1975 there were 8,000 FBI special agents, of whom 103 were black—still far below the percentage of blacks in the US population as a whole. ↩

-

2

Asked whether it had been re-evaluated after thirty days, as Kennedy had instructed, Courtney Evans told the Church committee, “I have no personal knowledge in this regard but I would point out for the information of the committee that the assassination of President Kennedy occurred within that 30-day period and that this had a great effect on what Robert Kennedy was doing.” ↩

-

3

The FBI bugs were placed in King’s hotel rooms in Washington DC, Milwaukee, Honolulu, Los Angeles, Detroit, Sacramento, Savannah, and New York City, between January 1964 and November 1965. ↩

-

4

On March 30, after Nicholas Katzenbach had become attorney general, he required that the FBI seek prior written approval of the attorney general before planting any bugs; later that summer Katzenbach gave Hoover permission to move without advance approval in “emergency circumstances.” The Church committee obtained from FBI files four memos stating that King’s hotel rooms in New York City had been bugged in May, October, and November of 1965, with approval after the fact. Although Katzenbach conceded that each memo “bears my initials in what appears to be my handwriting,” he professed to have no memory of reading or receiving them. Under questioning, however, Katzenbach declined to characterize them as forgeries. ↩

-

5

Since it was well known that Bradlee had been a close friend of the late President Kennedy, he assumed the derogatory reference to Jacqueline Kennedy was mentioned in an effort to pique his interest in looking at the transcript. That, he said, is what he meant by saying that DeLoach had “kind of hustled” the transcript. ↩

-

6

But the FBI did not stop spreading rumors to reporters about King’s alleged extramarital activities. If Johnson did speak to Hoover, there is no record of it; what evidence does exist suggests that LBJ was annoyed not with the FBI, but with Bradlee for talking to Katzenbach. According to a memo by DeLoach of December 1, 1964, Bill Moyers told him Johnson had heard that a newsman (Bradlee, whose name was deleted from the memo as published by the Senate intelligence committee) was “telling all over town” about the FBI bugging King. Moyers said “the President wanted to get this word to us so we would know not to trust” the reporter, DeLoach wrote. ↩

-

7

Various reporters were apparently offered transcripts of the King bugs by the FBI. David Kraslow, chief of the Washington bureau of the Cox newspapers, said that an FBI source had telephoned him—he thought it was late in 1964 or early in 1965—to offer a transcript of an interesting tape. Kraslow then was a reporter for The Los Angeles Times in Washington. Kraslow said the FBI official began reading from a purported transcript showing King allegedly participating in a sex orgy. Kraslow interrupted the FBI man and said he did not wish to listen to any more. He declined to identify his FBI source. ↩

-

8

The FBI’s top public relations man was unhappy at Hoover’s comment. “I was with Hoover at the time,” DeLoach testified. “ I passed Mr. Hoover a note indicating that in my opinion he should either retract that statement or indicate that it was off-the-record. He threw the note in the trash. I sent him another note. He threw that in the trash. I sent a third note, and at that time he told me to mind my own business.” ↩

-

9

Who wrote the letter was a matter of dispute. The text quoted at the Church committee hearings was, according to the FBI, found in the files of William Sullivan some time after he was forced out by Hoover. Sullivan claimed that the draft was a plant written by someone else and placed in his files to embarrass him. ↩

-

10

Sullivan testified he was told by Belmont that Hoover wanted the tape mailed to Mrs. King to break up her marriage and diminish King’s stature. ↩

-

11

Although the whole purpose of the exercise was to mail the tape to Coretta King, the FBI agent who went to Florida told the Sentate intelligence committee that he had mailed it to “Martin Luther King, Jr.” on Sullivan’s instructions. Andrew Young said the tape was received at SCLC headquarters in Atlanta and later sent to King’s home. ↩