François Ponchaud is a French priest who spent ten years in Cambodia and left three weeks after the so-called “democratic” revolution took place in April, 1975. He spoke Khmer so well that he was made a member of a local committee of translators. Since being expelled with the rest of the foreigners he has made intensive efforts to find out what has happened in Cambodia, listening to the official radio, examining every available public document, compiling evidence from some hundred refugees in Thailand, Vietnam, and France.

His book Cambodge, année zéro is by far the best informed report to appear on the new Cambodia, the most tightly locked up country in the world, where the bloodiest revolution in history is now taking place. What Oriental despots or medieval inquisitors ever boasted of having eliminated, in a single year, one quarter of their own population? Ordinary genocide (if one can ever call it ordinary) usually has been carried out against a foreign population or an internal minority. The new masters of Phnom Penh have invented something original, auto-genocide. After Auschwitz and the Gulag, we might have thought this century had produced the ultimate in horror, but we are now seeing the suicide of a people in the name of revolution; worse: in the name of socialism.

Of course it is horrible when Pinochet tortures his prisoners, Amin strangles his enemies, and the extreme Franco-ist guerrillas massacre theirs; but what else do we expect from people whose main work is simply killing and who are ruled only by a tyrant’s caprice? What has taken place in Cambodia during the last two years is of a different historical order. Here the leaders of a popular resistance movement, having defeated a regime whose corruption by compradors and foreign agents had reached the point of caricature, are killing people in the name of a vision of a green paradise. A group of modern intellectuals, formed by Western thought, primarily Marxist thought, claim to seek to return to a rustic Golden Age, to an ideal rural and national civilization. And proclaiming these ideals, they are systematically massacring, isolating, and starving city and village populations whose crime was to have been born when they were, the inheritors of a century of historical contradictions during which Cambodia passed from a paternalistic feudalism, through colonization, to a kind of precapitalism manipulated by foreigners.

François Ponchaud’s book not only gives shocking, detailed, and carefully authenticated testimony confirming earlier reports of mass suffering being inflicted on the Cambodians. He quotes from texts distributed in Phnom Penh itself inciting local officials to “cut down,” to “gash,” to “suppress” the “corrupt” elites and “carriers of germs”—and not only the guilty but “their offspring until the last one.” The strategy of Herod. He cites telling articles from the government newspaper, the Prachachat, including one of June 10, 1976, which denounced the “reeducation” methods of the Vietnamese as “too slow.”

The Khmer method has no need of numerous personnel. We’ve overturned the basket, and with it all the fruit it contained. From now on we will choose only the fruit that suit us perfectly. The Vietnamese have removed only the rotten fruit, and this causes them to lose time. [Italics added]

Perhaps Beria would not have dared to say this openly; Himmler might have done so. It is in such company that one must place this “revolution” as it imposes a return to the land, the land of the pre-Angkor period, by methods worthy of Nazi Gauleiters.

François Ponchaud’s book can be read only with shame by those of us who supported the Khmer Rouge cause. It should be shaming as well to those in the Nixon administration who bombed and laid waste Cambodia, undermining Sihanouk’s regime, and refused to pursue negotiations with him in Peking, making an unmitigated Khmer Rouge victory all the more likely. And it will cause distress to those of us journalists who, after the massacre of seventeen of our colleagues in April and May 1971, tried to explain these deaths as part of the hazards of covering a disorganized guerrilla war. In fact our poor comrades were assassinated—some, we now know, clubbed to death—by the valiant guerrillas of Khieu Samphan, the “socialist” Khmer who now bars foreign observers from Cambodian soil. His people remain in terror-stricken confinement, one of this regime’s more rational decisions: for how could it let the outside world see its burying of a civilization in pre-history, its massacres? When men who talk of Marxism are able to say, as one quoted by Ponchaud does, that only 1.5 or 2 million young Cambodians, out of 6 million, will be enough to rebuild a pure society, one can no longer simply speak of barbarism; what barbarians have ever acted in this way? Here is only madness.

Advertisement

On finishing Ponchaud’s book I wondered why, after the Bertrand Russell tribunal, which justly indicted US aggression, there should not be a new public tribunal to consider and denounce such crimes, committed in the name of revolution. For may not the most sinister crimes of all be those that betray the principles of socialism and assassinate human hope itself?

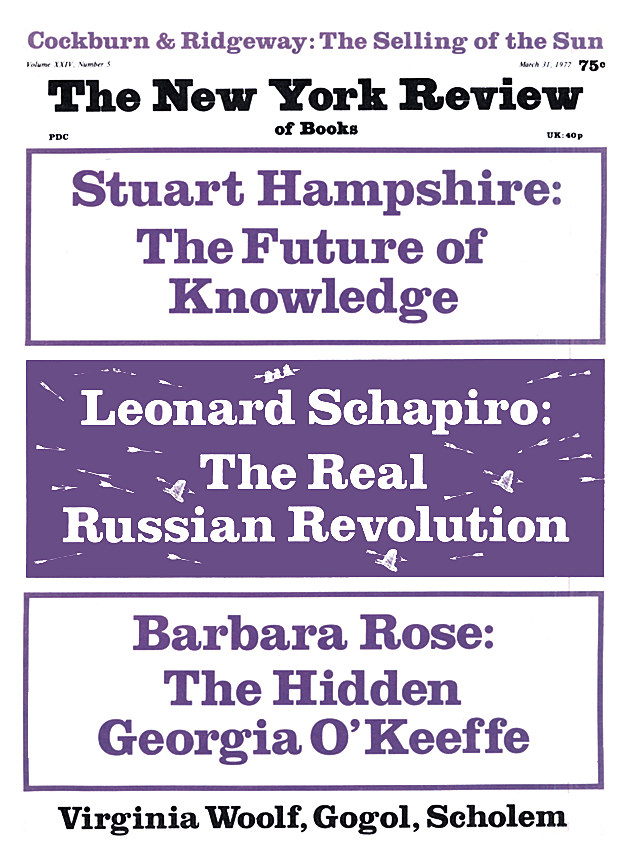

This Issue

March 31, 1977