One can say much in the first person, and during the last twenty years or so many American novelists have imagined they could say virtually anything. But the “I” presents problems, limits, unwonted consequences, too:

I was born right here in Clarion; I grew up in that big brown turreted house next to Percy’s Texaco. My mother was a fat lady who used to teach first grade. Her maiden name was Lacey Dabney.

This paragraph opens the second chapter of Anne Tyler’s Earthly Possessions, and it is very arch. What do I know about “that” house, or Clarion, or Percy, that I should be thus invited in; if I accept the invitation, what can I make of someone who calls her mother “a fat lady,” or who imagines, without seeming herself to care, that I need to know the fat lady’s maiden name? Nor do matters improve when she starts speaking of herself:

These were my two main worries when I was a child: one was that I was not their true daughter, and would be sent away. The other was that I was their true daughter and would never, ever manage to escape to the outside world.

Thus twelve years, or, as it turns out, thirty-five, of Charlotte Emory’s life are reduced to a cartoon, and by her own hand, the possible anguish is then lost.

If what Anne Tyler had intended were a cartoon, then all might be well; Thomas Berger works rather successfully with the first person and with such cartoon figures. But Tyler is not writing Who Is Teddy Villanova? or Portnoy’s Complaint or Why Are We in Vietnam? or other first-person extravaganzas. Earthly Possessions, at least in its best moments, is a straightforward realistic novel about Charlotte Emory’s abduction by Jake Simms, a pathetic young man who is trying to rob a bank just as Charlotte is standing in line to draw out her savings so she can at last leave home. The robbery fizzles, Simms takes Charlotte as hostage by bus to Baltimore and then by car to the South. All the coy parts of the novel, the writing that is at once glib and strained, come not in the story of the getaway but in alternating chapters which describe Charlotte’s past as one of the depressed and zany inmates of “that big brown turreted house.” To add to the awkwardness, Tyler won’t let Charlotte allude in the present to anything in her past until the retrospective chapters can explain the references.

We have had enough, perhaps, of titles like Earthly Possessions—Foreign Devils, Fear of Flying, End Zone—titles themselves arch, novels that even at their best deprive the private lives they describe of dignity with a nervous or cute prose. Tyler’s novel could have been called Charlotte and Jake, and, had it been, she might better have seen how much her patient and unhurried dialogue can reveal all we need to know about Charlotte’s past just by showing us the person she is. Since the best effects of the writing are cumulative, short quotations don’t work very well, but here are Charlotte and Jake, two days out from Clarion:

“Well, for goodness sake,” I said. I felt insulted. “Why would I do that? All I want is a little sleep. Lock the door, if you like.”

“No way of doing that.”

“Get another chain from somewhere.”

“What, and lock myself in too?”

“You could keep a key. Find one of those—“

“Lay off of me, Charlotte.”

I was quiet for a while. I studied snuff ads. Then I said, “You really ought to get over this thing about locks, you know.”

“Lay off, I said.”

I looked for a radio, but there wasn’t one. I opened the glove compartment to check the insides: road maps, a flashlight, cigarettes, boring things like that. I slammed it shut. I said, “Jake.”

“Hmmm.”

“Where’re we going, anyway?”

He glanced over at me. “Now you ask,” he said. “I was starting to think you had something missing.”

A woman who was afraid as a child that she would never escape from home being taken just as she was about to leave; a young man who has insistently failed to make anything work in his life; the two not just becoming clear, but establishing some relationship with each other.

Jake thinks he is going somewhere. To Perth, Florida, where an old buddy now lives because his mother “never did think much of me, moved Oliver clean away from me”; first, though, he goes to Linex, Georgia, to pick up Mindy, seventeen and pregnant by him, at a home for unwed mothers:

“Well, at first I thought she was too young and besides I didn’t like her all that much but I couldn’t seem to shake her. She was forever hanging around and didn’t take offense when I sent her away but went off smiling, made me feel bad. Just a little gal, you know? It was summer and she wore those sandals like threads, real breakable-looking. Finally it just seemed like I might as well go on out with her.”

When she appears, Mindy doesn’t help much, she and Jake tangle, and Jake comes increasingly to rely on Charlotte’s blankness, which he gradually understands as her trust of him. Tyler is excellent at making this blankness expressive; at the beginning, for instance, it is unnerving that neither of them mentions sex, but slowly Tyler shows that this is the result of Charlotte’s being so absorbed in the trip that she seems in a cocoon, while Jake is too involved in his own determination to fail. Yet this sexlessness is what, at the end, brings them together, as Charlotte is about to leave:

Advertisement

“I’m leaving now,” I told him.

His mouth fell open.

“I can’t stay on forever, Jake. You knew I’d have to go sometime.”

“No, wait,” he said. His voice had turned harsh and raspy.

“Tell Mindy goodbye for me.”

“Charlotte, but…see, I can’t quite manage without you just yet. Understand? I’ve got this pregnant woman on my hands, got all these…Charlotte, it ain’t so bad if you’re with us, you see. You act like you take it all in stride, like this is the way life really does tend to turn out. You mostly wear this little smile. I mean, we know each other, Charlotte. Don’t we?”

“Yes,” I said.

Yet in the alternating chapters, even near the end of the novel, the characters are still habitually given to false summarizing. “It’s not me that you’ve fooled, it’s yourself,” and “I have spent my life at the Clarion P.T.A.” Knowledge comes slower and harder in the best of the novel, and there is no way to summarize it; I only wish Anne Tyler had retrieved Charlotte and Jake, the fine short novel that got lost in Earthly Possessions.

Who is Teddy Villanova? is first person and extravagant, not so much a parody of Hammett and Chandler as a confident, exceedingly literary adaptation of the form, Seventies cool rather than Forties bite. Here we are, private eye and secretary, in the early pages:

“Gawd, I’m still hungry,” she said with the same righteousness as that in which Zola penned the memorable J’accuse. “I couldn’t afford Blimpie’s Best. I had to take Number One, all roll.”

“I haven’t had the leisure for lunch, myself,” said I. “I was savaged by the gigantic hoodlum you nonchalantly admitted. I called for help, but—God’s blood!—you were already gone.”

“I don’t have to take that type language,” she asseverated in her fire-siren voice, her plump breasts bouncing. “My brother’d pound you to a pulp if he heard you.” I didn’t know to which brother she referred, the sanitation union functionary or the one who was a petty timeserver in Queens Borough Hall, sans power to fix a traffic ticket, or perhaps merely the inclination to exert it: earning him, at any rate, a deafening blow on the ear from an offended cousin at one of the Tumulty family’s Thanksgiving Donnybrooks.

This may be likable, but it is hard to imagine anyone liking a whole book of it. Chandler’s style was often ornate and self-conscious. To make that style only words calling attention to themselves seems more an occupation for a late-night competition among friends than for a novelist.

Some sections are tedious: an episode with cops named Calvin, Knox, and Zwingli; a yoga teacher in Greenwich Village; a Maltese Falcon, here called a Sforza figurine. But by the time I reached the figurine, late in the novel, I was unexpectedly enjoying myself, because the story is good enough to keep Berger himself interested in what he is doing. If you enjoy private-eye novels presumably you do so because you like the mode, but what distinguishes a good from a bad one is the way the story reveals materials that in some way are being savored rather than simply used. Berger’s story is nonsense. Cops and fake cops, dead bodies that reappear but were never dead, alliances that shift so frequently that at some moment everyone except the hero is or seems to be an ally or enemy of everyone else, and, governing all, Teddy Villanova, who may commit murders, or counterfeit money, or run brothels for fetishists, or sell office buildings, or deal in obscene art objects on classical themes—or, most likely, not exist at all, in which case the problem is who invented him.

Advertisement

What the story manages to express, however, far better than the comments on the subject made by Berger’s hero, is a view of New York. When a cop says “Did you cause that man to shuffle off his mortal coil?” I feel embarrassed, as much by its inanity as coming from New York’s police as by the limpness of the joke. But when the swirling tale leads the private eye from being saved from arrest by the Gay Assault Team, to sleeping all night in a Barca-Lounger left on a sidewalk in front of a brown-stone, to a gunning down in Union Square, to a high-rise where a stewardess who may be a Treasury agent lives, then the motion itself expresses a decadent, improbable, fascinating wilderness that is familiar enough to be plausible and distinctive, too. The hero is beyond conspiracy theories about the city, despite the countless possible conspiracies against him, because nothing, and no one, surely, could have thought up New York.

Someone, though, is plotting against our hero, and maybe, indeed, it is his landlord, who wants only to get him to move so he can sell the office building; it might take that much to get someone out whose rent is frozen and whose funds are low. Finally, in a good last series of scenes, the plot comes back, as it should, to the original situation of a man, his secretary, and an unredeemable office building on East Twenty-Third Street, expressing as it does so a piquant sense of what it takes for people to live, work, and make money in a city where everything moves but nothing works.

In this novel the first person seems fully justified. Everything the hero sees is simply out there, existing not to be understood but to be encountered, and, if possible, accepted, and everything the hero is can be said in mannered prose since he is a figure without inwardness or complexity. At the end the hero is as he was at the beginning, but given what has happened, this is an accomplishment. He is on the phone with a final claimant to the name of Teddy Villanova, and the secretary, who appears more and more full of guile as the story goes on, has just asked him if he is queer as she disappears into the bathroom:

I had enough of this. I still had to answer Peggy’s insulting question. “Well, ‘Teddy,’ you are a raffish fellow indeed, but my presence is required elsewhere.”

“If it’s with those Stavrogin tots, be careful; they’re police plants, old boy. If you crave green fruit, come visit me in Bavaria.” He proceeded to specify certain amusements that I could not entertain even in joke.

I hung up, went to the bathroom door, and cried: “No, I’m not a homosexual, nor zoophile, pederast, pedophile, flagellant, nor fetishist!”

I went across the room, and, in defiance, sat upon the defaced suede chair; my trousers were anyway streaked with pigeon dung.

“Glad to hear that,” said Peggy, opening the door and emerging in my old mulberry bathrobe.

And so to bed, the rat-tat-tat of the language finally over. Who Is Teddy Villanova? is a good, accomplished minor novel; in these puffed up times I hope one can still offer such a judgment as genuine praise.

Ceremony, Leslie Marmon Silko’s first novel and a work of such lofty ambition that only the highest praise would suit were it all it aspires to be. No first person here, no stylistic highjinks, no willingness, even, to admit that story is primarily a literary method. Silko is part Laguna Pueblo, and what she intends in Ceremony is nothing less than a means of regeneration for a people. “This novel is essentially about the powers inherent in the process of story-telling,” she writes: “I feel the power that the stories still have to bring us together, especially when there is loss and grief.” They do, and this one does, though Silko can name the loss and grief much better than she can evoke the bringing together. The time is 1946, the place a bar in New Mexico:

“We fought their war for them.”

“Yeah, that’s right.”

“Yeah, we did.”

“But they’ve got everything. And we don’t got shit, do we? Huh?’

They all shouted “Hell no” loudly, and they drank the beer faster, and Emo raised the bottle, not bothering to pour the whiskey into the little glass any more.

“They took our land, they took everything! So let’s get our hands on white women!” They cheered. Harley and Leroy were grinning and slapping each other on the back.

It’s not the first time these men have sat thus, nor will it be the last. These are the Indian veterans, home, decorated, back on the reservation, hating and hateful.

There is another veteran, a half-breed named Tayo, son of an Indian whore, who has spent his first years grubbing in an arroyo near Gallup, waiting for his mother to pay her daily visit. At four he goes to live with his aunt, and he never sees his mother again; his aunt can never forget where he came from. Tayo grows up in the shadow of his cousin Rocky, the good student and star athlete who would make it in the white world, except that Rocky dies in the Bataan Death March, Tayo alongside. Tayo returns, physically wasted, emotionally destroyed, a victim of horrible dreams and fits of uncontrollable crying. At first Tayo goes to the bars with Emo, Harley, Leroy, and the others, and listens to them remembering the good times of the war, when their uniforms kept them from being treated as Indians. But then he blows the whistle on them:

“The war was over, the uniform was gone. All of a sudden the man at the store waits on you last, makes you wait until all the white people bought what they wanted. And the white lady at the bus depot, she’s real careful now not to touch your hand when she counts out your change.”

The others hate Tayo because he is right, and they are left with only a windblown reservation, beer, and Emo’s cry: “They took our land, they took everything!”

Everyone depends on memories—the veterans remember the war, the aunt her son, and Tayo is his own Gerontion:

Tayo looked up at the big orange sandrock where the wild grape vine grew out of the sand and climbed along a fissure in the face of the boulder. Harley picked some more. He ate them in big mouthfuls, chewing the seeds because most of the grape was seed anyway. Tayo could not bite down on the seeds. Once he had loved to feel them break between his teeth, but not any more. The sound of crushing made him sick. He got up and walked the sandy trail to the spring. He didn’t want to hear Harley crush the seeds.

Tayo also remembers his uncle, Josiah, and a herd of desert cattle he bought just before the war and then lost because those helping him went off to be soldiers. And a woman Josiah used to go to who seduced Tayo one day, thereby telling Tayo most of what he can know about his mother.

Most astonishing is the memory of the Laguna Pueblos—one knows no better way to say it—because Leslie Silko was born in 1948 and could have known none of this first hand. She speaks of the power of stories, and these opening pages, clear and strong, are ample witness to that power. Somehow the shards of lives, pain and loss became stories Silko could not only hear but understand, write down, amplify. I can’t remember when I have read the work of a woman who writes with such ease and assurance about the lives of men. The opening of Ceremony made me remember other books I have admired about soldiers coming home, Niven Busch’s They Dream of Home, and John Okada’s No-No Boy, and I know of no one who has been clearer about what it was like than Leslie Silko.

Tayo’s aunt sends him to a medicine man, who tries to help but soon sends him on to Betonie, who lives in a shack near the arroyo where Tayo was born, where there are boxes of “antennas of dry roots and reddish willow twigs,” and “piled to the tops of the WOOL-WORTH bags were bouquets of dried sage and the brown leaves of mountain tobacco,” and “bundles of newspapers, their edges curled stiff and brown, barricading piles of telephone books with the years scattered among cities—St. Louis, Seattle, New York, Oakland.” No one’s idea of a medicine man, and all Betonie will say at first is “don’t try to see everything all at once…we’ve been gathering these things for a long time.” “I just need help,” Tayo says. “We all have been waiting for help for a long time,” Betonie answers; “The people must do it. You must do it”:

There was something large and terrifying in the old man’s words. He wanted to yell at the medicine man, to yell the things the white doctors had yelled at him—that he had to think only of himself, and not about the others, that he would never get well as long as he used words like “we” and “us.” But he had known the answer all along, even while the white doctors were telling him he could get well and he was trying to believe them; medicine didn’t work that way, because the world didn’t work that way. His sickness was only part of something larger, and his cure would be found only in something great and inclusive of everything.

For the other veterans the sickness is the white man, but they themselves are sick and need to stay drunk to avoid seeing this. For Tayo’s aunt the sickness needs no diagnosis, only the cure of timeless rituals. Betonie, with his herbs, rags, and phone books, knows the ceremonies that can heal are never timeless, but changing; no Indian can ever again act as though the whites had not come, or as though the whites did not themselves need to be cured. Witchery, says Betonie, is the enemy: “Witchery works to scare people, to make them fear growth.” For the Indians such fear leads to frozen memories and despair, for the whites it leads to trying to possess the land as though it were dead. To cure either will take a new ceremony.

Leslie Silko’s success in the first hundred pages of her novel seems of immense promise. But already one sees in the impressive exchange between Tayo and Betonie a slackening of Silko’s hold on her language; to say “his cure would be found only in something great and inclusive of everything,” or that “witchery works to scare people, to make them fear growth,” is to get dangerously close to sloganeering, and to make us remember that Silko came of age in the Sixties. Her assurance, her gravity, her flexibility are all wonderful gifts, but what she is trying to write in the second half of Ceremony is nothing less than holy scripture. She knows, as did the authors of other scriptures, that Betonie’s is a voice crying in the wilderness, and that Tayo cannot suddenly become a leader of his people, with banners waving. She must follow Tayo, and hope only that he can bring new life. But she puts such a burden on this hope that the book begins to waver and insist too much.

Still, there is one good episode, where Betonie’s prophecy leads Tayo to look for the lost desert cattle, which he finds behind some marvelously built barbed-wire fences of a white rancher. Tayo cuts the wire, begins to collect the cattle, but is caught by ranchers, who would put him in jail except that they are enticed off to hunt a mountain lion that they then lose in a blizzard. What is proper here is Silko’s sense of scale: we feel that if Tayo can regain the cattle a new start of some kind will be made.

But Silko doesn’t trust her tale here, and she begins to preach, and familiar sermons at that:

He stood back and looked at the gaping cut in the wire. If the white people never looked beyond the lie, to see that theirs was a nation built on stolen land, then they would never be able to understand how they had been used by the witchery; they would never know that they were still being manipulated by those who knew how to stir the ingredients together: white thievery and injustice boiling up the anger and hatred that would finally destroy the world: the starving against the fat, the colored against the white.

Silko was right, I am sure, to abjure the first person and to insist that her stories are collective, but it must then be added that the Indians do not know what the new story, the new ceremonial action, will be. In Ceremony all is pretty much lost after Tayo comes back from the blizzard. He meets a woman who knows all, shares all, and is very mysterious. He goes back to the reservation to watch the other veterans kill each other in a bloodbath, resisting the temptation, as new heroes must but as even cowards might, to join in himself. At the very end, the inevitable sunrise.

It is not a question of agreeing or disagreeing with Silko’s diagnosis any more than it is of sharing Thomas Berger’s vision of New York or of believing in Anne Tyler’s heroine’s childhood and its fears. With novels a reader can believe anything, or not, as he chooses. The real question lies elsewhere, in the response to the integrity of the language and to the strength of the tale. Berger will doubtless find his audience; his book, with its manner of savvy, bizarre amusement that is fashionable right now, is good of its kind. With Tyler and Silko it is harder to say; perhaps the gravest danger for them, especially for Silko, will be finding readers at once less responsive and more gullible than they deserve.

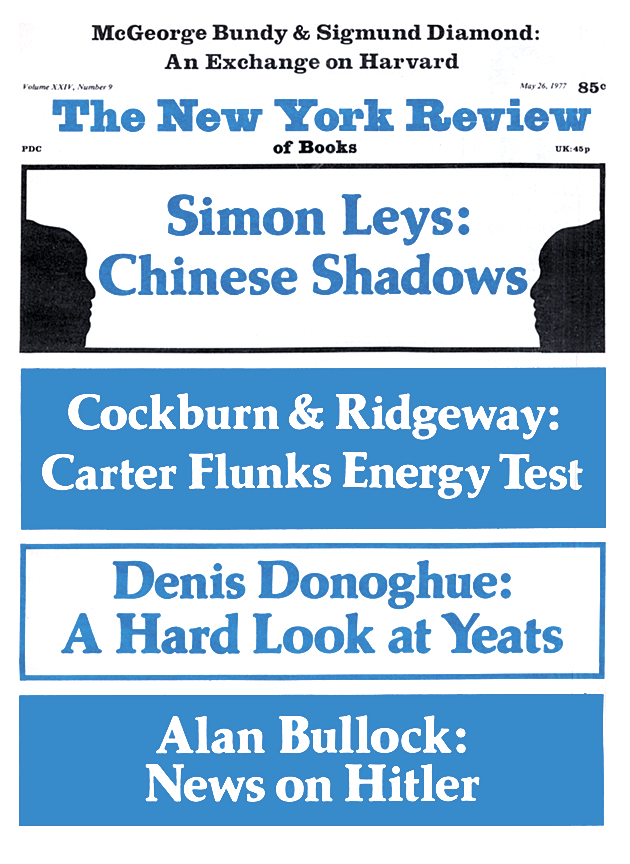

This Issue

May 26, 1977